A series of multi-track optical soundtracks used for the reproduction of stereophonic sound.

Film Explorer

Identification

B/W, color.

1

Experiments for Loews, Inc. included those made on Ansco Color print stock.

Two channels of directional sound – later with a third audio and fourth control track – were recorded in parallel variable-density tracks, to the left of the image.

(plus control track)

B/W, color.

History

An extension of experimental binaural recordings by Bell Telephone in the early 1930s, Electrical Research Products, Inc. (ERPI), a Western Electric subsidiary, demonstrated the first practical application of stereophonic sound in motion pictures in 1937. Stereophonic tests had been made as early as 1931, with work done by Alan Blumlein for EMI in England, but the end results of ERPI’s system were planned to be manufactured on an industrial scale for theaters internationally. The head of ERPI’s binaural development was Joseph P. Maxwell, who had been a supporter of binaural recording for mixing balance as early as 1935, when the musical score to Columbia Pictures’ Love Me Forever was recorded with multiple orchestral angles for mixing.

Following the implementation and success of two-track, push-pull soundtracks for recording, as well as binaural balance recordings of music on two-track optical sound, ERPI evolved the idea into a two-channel, left–right optical soundtrack for standard prints. ERPI demonstrated its results with a 15-minute proof-of-concept film, which included a ping-pong game, a woman playing a piano – and sound effects in a dark room, designed to allow the audience to follow the movement of certain objects, before the lights are turned on. This film was initially presented at an October 1937 conference of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, held in New York City. According to a Variety article, the initial screening presented some technical difficulties – as a result, additional screenings were held the following month at the General Service Studios in Astoria, Queens, New York.

While ERPI continued to refine the process, Western Electric’s parent company, Bell Telephone, transferred its research and development of stereophonic film soundtracks to AT&T, who were developing Fantasound at the same time. Refining Fantasound’s three-channel and control track arrangement, ERPI augmented its standard release print version in 1941 to add a third audio channel and a control track.

Following this work in the early 1940s, ERPI Stereophonic was shelved until 1953, when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s audio department head Douglas Shearer experimented in reviving the process to add stereophonic sound to CinemaScope films without striped magnetic oxide tracks. Loews Inc., who had already invested in Perspecta Sound, decided against using the system, although at least one reel of Kiss Me Kate (1953) was printed with this system for a demonstration.

Selected Filmography

Reel one of this film was used as a demonstration for the three-track variety of the system. The film’s original three-channel magnetic tracks were mixed down to optical tracks by MGM sound department head Douglas Shearer. It was not included in the film’s general release.

Reel one of this film was used as a demonstration for the three-track variety of the system. The film’s original three-channel magnetic tracks were mixed down to optical tracks by MGM sound department head Douglas Shearer. It was not included in the film’s general release.

A film made for demonstration at the 1937 Society of Motion Picture Engineers convention. As per a description in International Projectionist:

“The reel of Stereophonic recordings demonstrate this effect. In one sequence a woman plays a short piano selection, and the notes of the piano actually come from the strings behind the keyboard, and the distance between the bass and treble strings is easily discerned. In another scene a large symphony orchestra plays. The location of the choirs or individual musicians in the orchestra is easily discerned by the sound coming directly from each instrument.

A short skit is also presented which opens with a darkened screen. A clock is heard striking and the audience involuntarily looks to the right of the screen to see it. A telephone rings and the audience looks to the opposite side to see it. When the lights come up revealing a living room set, the clock and telephone are in the exact positions in which the audience had looked.”

A film made for demonstration at the 1937 Society of Motion Picture Engineers convention. As per a description in International Projectionist:

“The reel of Stereophonic recordings demonstrate this effect. In one sequence a woman plays a short piano selection, and the notes of the piano actually come from the strings behind the keyboard, and the distance between the bass and treble strings is easily discerned. In another scene a large symphony orchestra plays. The location of the choirs or individual musicians in the orchestra is easily discerned by the sound coming directly from each instrument.

A short skit is also presented which opens with a darkened screen. A clock is heard striking and the audience involuntarily looks to the right of the screen to see it. A telephone rings and the audience looks to the opposite side to see it. When the lights come up revealing a living room set, the clock and telephone are in the exact positions in which the audience had looked.”

Technology

The original 1930s track arrangement used the normal 0.10 in (2.54mm) optical track scanning area, the width of the track was divided into two separate 0.05 in (1.27mm) density tracks side-by-side, each track carrying a “left-ear” or “right-ear” audio channel in phase.

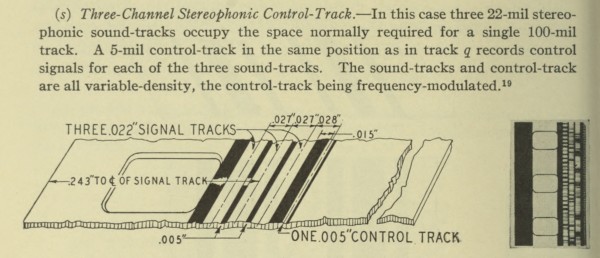

In its revised 1940s variation with a control track, and with having to stay within the standardized 0.10 in scanning area for the track, the three channels were evenly arranged in 0.027 in (0.69mm) tracks, buffered by 0.005 in (0.127mm) blank areas, as well as a frequency-modulated control track closest to the picture area, measuring 0.005 in (0.27mm).

Example of the final design for the ERPI Stereophonic system, three signal tracks and one gain control track.

Honan, E. M. & Keith, C. R. (1943). “Recent Developments in Sound-Tracks”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 41:8 (August): pp. 127–134.

An enlargement from the ping-pong table sequence from ERPI’s 1937 demonstration film.

Anon. (1937). “Notes on ERPI’s Stereophonic Sound Picture System”. International Projectionist, 12:11 (November): pp. 22–23.

References

Anon . (1937a). “Inside Stuff – Pictures”. Variety (November 24): p. 17.

Anon. (1937b). “Notes on ERPI’s Stereophonic Sound Picture System”. International Projectionist, 12:11 (November): pp. 22–23.

Honan, E. M. & C. R. Keith (1943). “Recent Developments in Sound-Tracks”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 41:8 (August): pp. 127–134.

Livadary, John P. & M. Rettinger, M. (1944). “Evolution of Scoring Facilities at Columbia Pictures”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 42:6 (June): pp. 361–366.

Patents

Followed by

Related entries

Author

Jack Theakston is a projectionist, archivist and film historian. He has spent two decades photochemically and digitally restoring films, and currently produces restorations through his company, 3-D Film Archive. Theakston is also a consultant for projection installations and historic theater management, and is a Union Projectionist specializing in 35mm and 70mm presentations. He resides in New York.

Bruce Lawton, Malkames Collection.

Theakston, Jack (2024). “ERPI Stereophonic”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.