A diagonally-running widescreen film format, for amateur moviemakers, which utilised Super 8 film.

Film Explorer

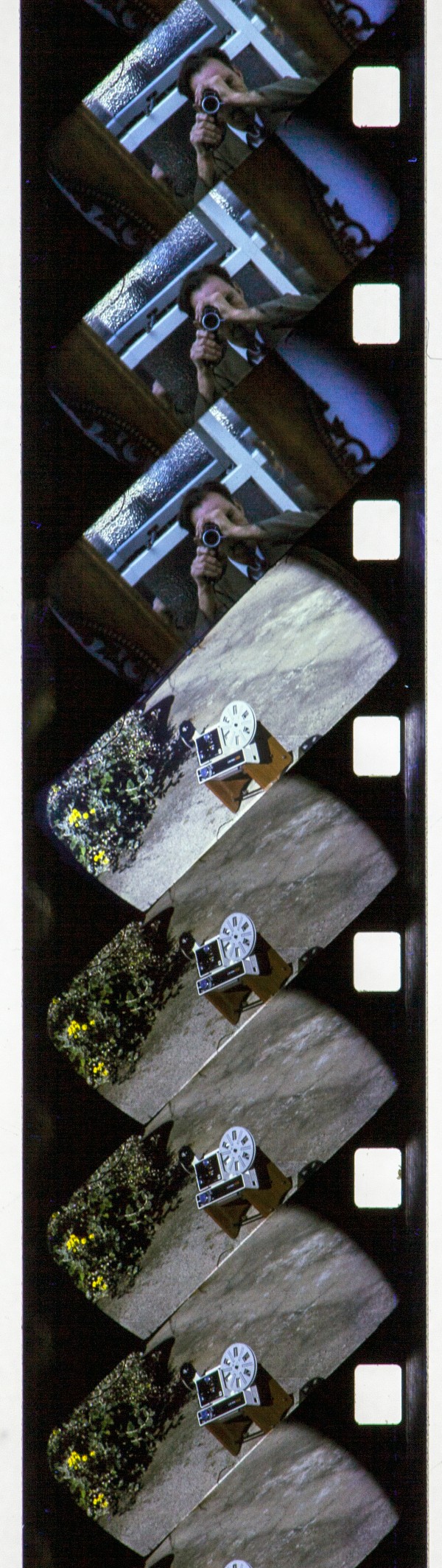

A short sequence from a Super 8 test reel, from 1975, showing the diagonally orientated Minirama frame.

Courtesy of Michael Jones.

Identification

7.37mm x 2.79mm (0.290 in x 0.110 in).

1

The format was planned for synchronisation with a soundtrack on Compact Cassette.

7.62mm x 2.92mm (0.300 in x 0.115 in).

Color, or B/W reversal.

Manufacturer’s edge markings could be seen in the image area.

History

Minirama was the third, and final, foray into film format engineering by the talented amateur cine engineer, P. Stuart Warriner. He carried out the design and conversion of equipment as an individual working within the context of a leading UK cine club named the Widescreen Association. The club encouraged a lively culture of engagement with amateur widescreen enthusiasts through its magazine, regional groups and a national annual convention called Widex. By Warriner’s own account, Minirama came about because, having presented his earlier 16mm-based formats (Pan 16 and Point Two), Widescreen Association members had asked him: “Why don’t you do something with Super 8????” (Warriner, 1976: p. 4). His response was the strikingly original idea of turning the frame through 45 degrees – and filming in the diagonal. Although a number of systems feature horizontal-running film – in opposition to the orthodoxy of vertical-running systems – this is thought to be the unique instance in film history of a diagonally oriented format. Accordingly, Warriner made new gate apertures for a GAF Super 8 camera, and a Eumig 610D projector, and succeeded in squeezing in a frame with an extra wide projected aspect ratio of 2.64:1 – “as near a ‘true scope’ format as you are likely to get” (Warriner, 1976: pp. 4–5).

Minirama received its first – and possibly sole – public demonstration at the 1977 Widex, held at Campus West, Welwyn Garden City. The editor of Widescreen, the club magazine, reported that: “With the souped up projector the system looked really good […] Stuart must have been throwing the picture a good 50 feet [15.24m] and the brightness was staggering” (Grimes, 1977: p. 4) However, unlike Warriner’s Pan 16 format, which secured the favour and patronage of some Widescreen Association members, there is no sign of further demand having existed for Minirama. It seems, at most to have been an elegant, curious ‘show pony’. Nevertheless, a surviving letter from Warriner allows one to imagine an alternative history, in which Minirama became a successful film format. The letter was written to his friend Brian Polden, a fellow member of the Association, and its technical officer and custodian of the club museum. It recounts an interaction with the main rep from Minolta, who: “appeared very interested as it seems they are looking out for a new gimmick now everybody is on Low Light and Sound Cameras, and who knows, this may be just what they are wanting. He asked me to keep it as dark as I can for the time being, so ‘Mum’s-the-word’” (Warriner, 1975).

Apart from its sheer idiosyncrasy, a significant disadvantage of Minirama was the encroachment of film manufacturer edge markings into the image area. This issue was familiar from some other experimental formats, such as Variscope.

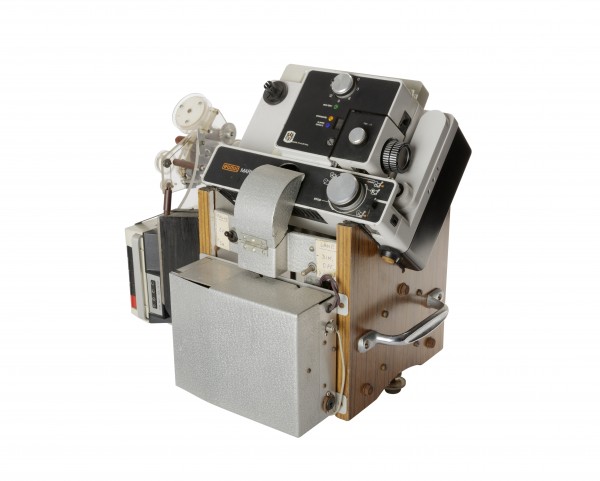

Warriner died in 1987, and in 2000 his local cine club, Morecambe Bay Moviemakers, of which he had been a founding member, offered his Minirama camera and projector to the National Media Museum in Bradford, England (now known as the National Science and Media Museum). The Curator of Cinematography, Michael Harvey, accepted it on the basis that it, “demonstrates the indomitable spirit of improvisation that characterised many amateur moviemakers and contrasts well with the conventional methods of producing widescreen pictures using anamorphic lenses” (Harvey, 2000).

Selected Filmography

The only known surviving film, is a strip of 13 frames, which was attached to the letter sent by Warriner to Brian Polden (Warriner, 1975). The letter and film strip survive at the National Science and Media Museum as part of the 2023 acquisition of the Widescreen Association Collection. Presumably part of a test reel, the film shows two shots, a self-portrait of Warriner shooting into a mirror, and an image of the projector in its cradle (first silent iteration).

The only known surviving film, is a strip of 13 frames, which was attached to the letter sent by Warriner to Brian Polden (Warriner, 1975). The letter and film strip survive at the National Science and Media Museum as part of the 2023 acquisition of the Widescreen Association Collection. Presumably part of a test reel, the film shows two shots, a self-portrait of Warriner shooting into a mirror, and an image of the projector in its cradle (first silent iteration).

Technology

The Minirama format consists of conversions to off-the-shelf Super 8 technology: a GAF 65 Auto Zoom camera; and a Eumig 610D projector. The camera gate and viewfinder were modified – and so, too, the projector gate. The interventions accommodated an extra-wide 2.64:1 image oriented diagonally on normal Super 8 film. Warriner also made a cradle to hold the projector at 45 degrees. The camera was simply tilted in the hand and although it, “raised a few funny looks from people who wonder ‘what the L is he doing?’”, it proved “perfectly comfortable in use” (Warriner, 1976: p. 4). “The modified equipment worked very well on completion, a small adjustment being made to the position of the lamp to improve the evenness of the illumination.” Later on, Warriner added a tape cassette player to the projector and its cradle, to allow for soundtracks to be synchonised to the film. He also installed a lamp conversion, to increase the brightness of the picture. This is the iteration which survives in the National Science and Media Museum.

References

Edmonds, Guy (2007). “Amateur Widescreen; or, Some Forgotten Skirmishes in the Battle of the Gauges”. Film History, 19:4 (“Nontheatrical Film”): pp. 401–13.

Edmonds, Guy (2023). “The Minirama Projector”. In Pelletier, Louis & Rachael Stoeltje (eds), Tales from the Vaults: Film Technology over the Years and across Continents. Brussels: FIAF, pp. 160–1.

Grimes, Bob (1977). “Editorial”, Widescreen, 13:2 (June/July): p. 4.

Harvey, Michael (2000). “Eumig 610D Super 8mm Projector and GAF 65 Auto Zoom Super 8mm Camera, Modified for Widescreen”. Offer 4484 (April 4). Bradford: National Science and Media Museum.

Warriner, Stuart (1975). “Letter to Brian Polden”. Pers. Comm . (October 12).

Warriner, P. Stuart (1976). “Minirama”. Widescreen, 12:2 (June/July): pp. 4–5.

Shapps, Tony (1987). “A Genius in His Own Time”. Widescreen, 23:2 (August/September): pp. 5–6, 14.

Patents

Compare

Related entries

Author

Guy Edmonds is a film restorer and archivist, who works at the National Library of Wales Screen and Sound Archive. He is an Associate Researcher with Transtechnology Research, at Plymouth University, where he completed his doctoral thesis, “Vibrating Existence: Early Cinema and Cognitive Creativity”, as a Marie Curie Fellow. He researches the affective dimensions of film technology, especially regarding the fields of early cinema, amateur cinema and experimental film. He has previously worked at the EYE Filmmuseum, Amsterdam, Christie's Camera auctions and The Cinema Museum, London, and holds an MA in Preservation and Presentation of the Moving Image from the University of Amsterdam.

Brian Polden, Tony Shapps, Toni Booth.

Edmonds, Guy (2024). “Minirama”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.