A 3-D format filmed with dual 65mm cameras and presented via two synchronized 70mm projectors with separate 35mm magnetic soundtrack. This format was used exclusively in theme park attractions at Walt Disney World, Florida, and Disneyland, California.

Film Explorer

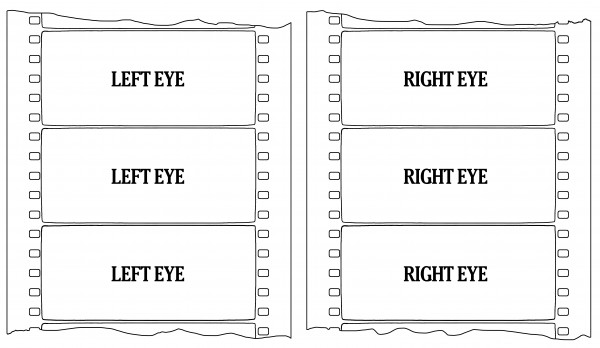

Side-by-side 70mm films strips for Disney 3-D presentation.

Illustration by Christian Zavanaiu.

Identification

48.56mm x 22.09mm (1.912 in x 0.87 in).

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

2

None

Because much of the Captain EO show focused on the music of Michael Jackson, his preferences dictated the large sound system requirements for the theater. Songs were recorded and mixed at Jackson’s home studio by Matt Forger who had worked with him since Thriller (1982). The THX theater mix was finalized by Jackson, Forger and Jon Snoddy from Lucasfilm. They spent many hours making minute adjustments until Jackson was happy. However, Disney executives thought the resulting mix was too loud, so they had Snoddy later rebalance everything to a lower level. Audio was played back in the theater from a 35mm full-coat magnetic track synchronized with the two 70mm projectors.

48.56mm x 22.09mm (1.912 in x 0.87 in).

Eastman Color Negative, 5247, 5293.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

History

The Eastman Kodak Company sponsored Magic Journeys (1982), a 70mm 3-D theater attraction for the opening of EPCOT Center at Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. This children’s fantasy film, designed to highlight the new format’s technological innovations, was directed by Academy Award winner Murray Lerner. During early pre-production, Disney Studios searched existing 3-D camera systems, including one built for Todd-AO by Panavision, but when none proved adequate for the film’s needs, they realized they would have to create their own system. Of primary interest was the higher resolution and brighter screen images available in a 70mm format that minimized the headaches and eye fatigue that plagued previous 3-D presentations.

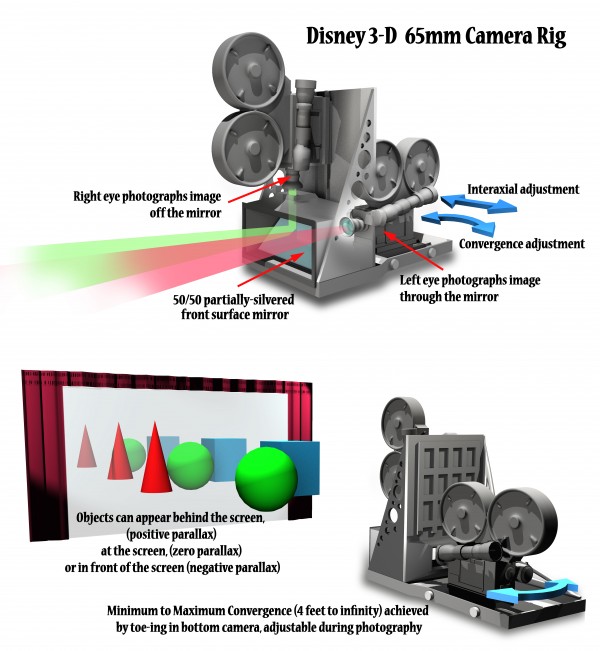

Historically, stereo photography has tried to match the actual separation of human eyes, but such a horizontal configuration of large and bulky 65mm cameras was never going to work. The favored arrangement was a vertical configuration of cameras and lenses. One camera is mounted pointing straight down and shoots into a 45-degree partially-silvered mirror. The second camera is mounted horizontally and shoots out through the same mirror. This design allowed for the lenses that could be positioned close to the human interocular (pupil-to-pupil distance) of 2.5 in (6.35cm).

Steve Hines, an engineer at WED, fabricated the original design, then worked with Bob Otto and Don Iwerks of the Disney studio machine shop in the final development of what became known informally as “the Hines rig”. Hines’s innovation allowed for the vertical (right-eye) camera to remain stationary while the second (left-eye) camera could be adjusted by a four-bar mechanical linkage within its hollowed-out base-plate. Changes could be made during photography to the interaxial distance, ranging from zero to 4 in (10.16cm) to create different perspective effects, such as making objects appear smaller, or larger, than lifesize. The left camera could also be shifted to “toe-in”, to adjust convergence – positioning objects in 3-D space from behind the screen (positive parallax) to well in front (negative parallax). Among the rig’s achievements was that these two adjustments – interaxial spacing and lens convergence – could be made independently of each other.

This rig would be required to do a lot that was innovative, because Lerner’s film called for scenes with blue screen, underwater shots, miniatures, macro, high-speed and time-lapse – all in high-fidelity imagery projected onto a 54-ft-wide (16.46m) screen. Eventually, other dual-camera rigs had to be built for the production: in addition to the main studio camera, a special set-up with a 12-ft (3.66m) interaxial distance was used for very wide vistas and clouds; and a side-by-side aerial rig for filming from a helicopter, with zero parallax (convergence being added and adjusted in post-production). A rig built by Ernie McNabb of the National Film Board of Canada, which had been used on a previous Lerner 3-D film, was modified for underwater photography. Magic Journeys set a high standard for future 3-D films, premiering at the opening of EPCOT Center, Florida, on October 1, 1982. The show also played at Disneyland, California, Tokyo Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom, Florida – finally closing for good in 1993.

The film that replaced Magic Journeys was an even more complex production, Captain EO (1986), a musical science-fiction short, starring Michael Jackson, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, and produced by George Lucas. In the past, making adjustments to the convergence and/or interaxial distance required downtime between set-ups – charts had to be consulted, as changing one variable could influence the other. While the original Disney rig had controls to make these changes independently and “on the fly”, the controls used pantograph linkages (using mechanical parallelograms) which were not always accurate, nor user-friendly. Starting with Captain EO, these adjustments were improved upon by cameraman Peter Anderson’s designs – replacing convergence and interaxial mechanisms with a single handheld zoom controller. When a second 3-D rig was needed for the show’s elaborate dance and action scenes, the production brought in the flat-plate dual-camera rig originally built by Todd-AO, even though its convergence and interaxial distances had to be set manually.

Captain EO played at EPCOT, Disneyland, Tokyo Disneyland and Disneyland Paris, closing during the late 1990s – replaced by Jim Henson's Muppet*Vision 3D. Among the innovations of the new film were the incorporation of in-theater 4-D effects, such as Audio Animatronics figures and elements like smoke and real soap bubbles. Honey, I Shrunk the Audience (1994), directed by Randal Kleiser, used the inherent flexibility of the rig’s ability to change interaxial spacing (lens divergence) to play with the viewer’s sense of scale of objects. After the death of Michael Jackson in 2009, a “Captain EO Tribute” was brought back to play in its original venues between 2010 and 2015. In keeping with Disney Imagineering traditions, all these theme park theatrical presentations were designed to be under 20 minutes long, to facilitate a daily three-shows-per-hour schedule.

Selected Filmography

A musical science-fiction short, starring Michael Jackson, made for Disneyland, Anaheim, California.

A musical science-fiction short, starring Michael Jackson, made for Disneyland, Anaheim, California.

Made for Disney/MGM Studio Tour, Florida, and Disneyland in California.

Made for Disney/MGM Studio Tour, Florida, and Disneyland in California.

Made for Disney/MGM Studio Tour, Florida. Later titled Muppet*Vision 3-D.

Made for Disney/MGM Studio Tour, Florida. Later titled Muppet*Vision 3-D.

Made for EPCOT Center, Orlando, Florida.

Made for EPCOT Center, Orlando, Florida.

Technology

The Disney 3-D rig consisted of two modified 65mm Mitchell cameras mounted with matched Hasselblad lenses (from 40mm to 150mm) and could run at 24, 48, or 72 fps (the latter two for slow-motion effects). As with most beam-splitter rigs, the 50/50 partially-silvered mirror blocked half the incoming light which resulted in the loss of one f/stop of exposure. For wide scenes requiring deep depth of field, a tremendous amount of light was needed in order to close the lens down to an f/8 or f/11 stop. For scenes of a circus high-wire act in Magic Journeys, so many lighting units were required that temperatures at the top of the stage set reached well over 100°F (37.8°C). At that time, the only film stocks available from Kodak were 5247 (ASA 125) and then, late in the production, 5293 (ASA 400).

Captain EO was filmed at 30 fps (which increases image fidelity but loses another 1/3 f/stop of exposure), requiring huge air conditioning units to be brought in very close to camera. Depending on filming speeds, cinematographer Peter Anderson sometimes rated the Kodak film stock at only ASA 10–20. Starting from this time, Anderson’s recommendation of shooting and projecting at 30 fps for any screen over 50 ft (15.24m) in width became the standard for Disney theme park filmed attractions.

With the design of the original Disney 3-D rig, the right-eye footage had to be flipped optically, because it was shooting into a mirror. Due to the unavailability on the studio lot of a suitable 65mm optical printer at the time, Magic Journeys had to use 35mm color reversal intermediates from the original 65mm negatives to accomplish this kind of optical realignment. At this intermediate stage, blue-screen, matting and other compositing work was completed, finally blowing the image back up to two (left and right image) 70mm prints for projection. By the time of Captain EO, a 65mm optical printer had been acquired from Alpha Cine in Colorado, resulting in a notable improvement in resolution. Also, by running the film in the stationary right-eye camera in reverse, back-to-front, the need for an optical flip to match the left-eye was eliminated.

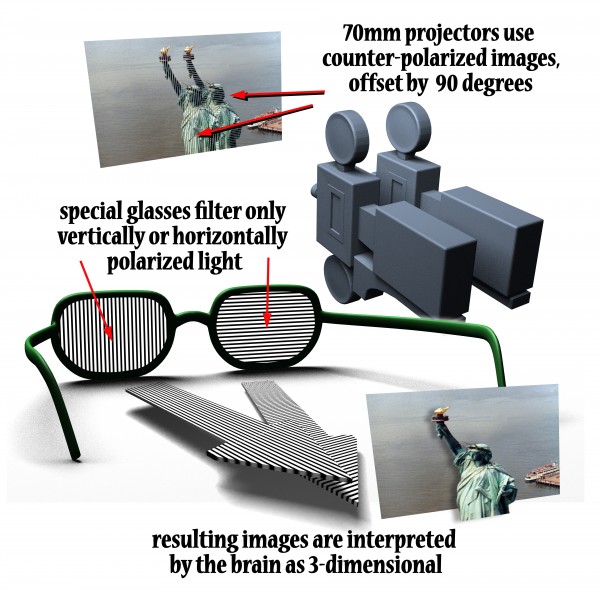

The Disney system used polarizing lenses on the projectors and passive polarized 3-D glasses worn by the audience. These operated somewhat like matching vertical and horizontal Venetian blinds, ensuring that, for example, the left eye of the viewer could see only the appropriate left-eye image. However, polarized glasses also darkened the overall illumination, requiring a compensating boost at the projector lamp house and the use of a silvered screen. While the brighter, high-resolution images made for a comfortable viewing experience that minimized 3-D’s usual headache-inducing eye fatigue, there was still the matter of the physical transport of film through two projectors by mechanical means. The problem of projector “weave”, caused by the slightest of variations in film print manufacture, as well as wear and tear on sprockets and gear teeth, would not be entirely eliminated until the advent of rock-steady digital 3-D projection.

As was standard for film presentations within Disney theme parks, the show’s projectors and film were housed in the theater while the soundtrack played from a central facility and was operated under the control of SMPTE code on a separate 35mm full-coat magnetic track.

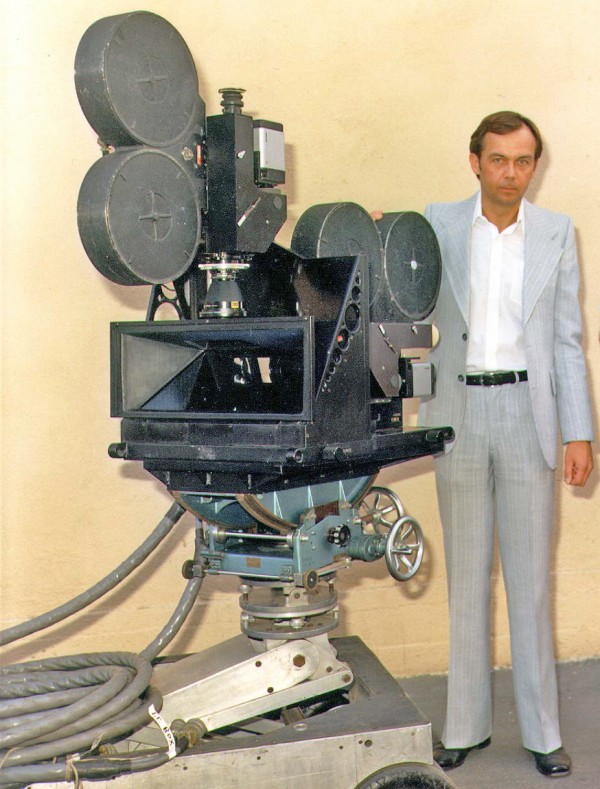

Disney 3-D rig featuring dual 65mm cameras shooting through a partially-silvered mirror. The unit was built with convergence and interaxial settings that could be adjusted independently during photography.

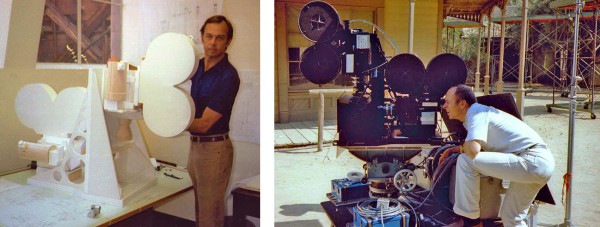

Steve Hines, HinesLab, Inc.

Peter Anderson (next to the ladder) filming with the Disney 3-D camera rig on a soundstage for Captain EO (1986).

Disney Studios.

Polarizing lenses, offset by 90 degrees, on both the projectors and in the viewing glasses.

Illustration by Jeff Blyth.

References

American Cinematographer (1983). “State-of-the-Art 3-D: Disney’s 65 mm 2-Camera System for MAGIC JOURNEYS”. American Cinematographer, 64:2 (Feb.): pp. 63–4, 84–90.

CineFex (1983). “Design of Disney’s 65 mm dual-camera 3-D rig”. CineFex, 11 (Feb.).

Iwerks, Don (2023). Interview with Jeff Blyth, Ojai, CA (September 6, 2023).

Reeve, Simon & Jason Flock (2010). “Basic Principles of Stereoscopic 3D”. https://www.ncl.ac.uk/media/wwwnclacuk/pressoffice/files/pressreleaseslegacy/Basic_Principles_of_Stereoscopic_3D_v1.pdf (accessed October 1, 2024)

Patents

Hines, Stephen P. & Walt Disney Productions. Camera assembly for three-dimensional photography. U.S. Patent 4,557,570, filed September 26, 1983, and issued December 10, 1985.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Jeff Blyth is a filmmaker who has made several Circle-Vision 360 films for Walt Disney Imagineering, including Wonders of China (1982) and Reflections of China (2003) for EPCOT, American Journeys (1984) for Disneyland and Walt Disney World (Writer and Co-Director with Rick Harper), Portraits of Canada for EXPO 86, and From Time to Time (aka Timekeeper) for Disneyland Paris and Walt Disney World (1992). He also wrote, produced, and directed the Circle-Vision 200 premiere attraction The Eternal Sea for Tokyo Disneyland (1983). He has authored the book Polishing the Dragons: The Making of EPCOT’s Wonders of China, published by Bamboo Forest Press, 2021. In addition, he has written and directed Light & Life (1991), an IMAX film for the centennial of Philips Lighting, Netherlands and worked as a producer/cameraman on the IMAX films, Behold Hawai’i (1983) and To Fly (1976). He directed the feature film Cheetah for Walt Disney Productions (1988), shot entirely on location in Kenya. He is a member of the Writer’s Guild of America, the Director’s Guild of America, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Documentary Branch.

Don Iwerks, Peter Anderson, Jon Snoddy, Rick Rothchild, Steve Hines.

Blyth, Jeff (2024). “Disney 3-D”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.