Film Explorer

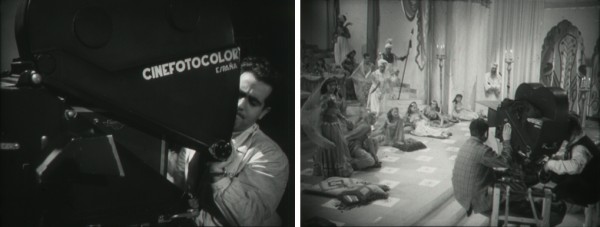

Tres eran tres (1954).

Filmoteca Española, Madrid, Spain.

Debla, la virgen gitana (1950).

Filmoteca Española, Madrid, Spain.

Identification

Copies were printed on a B/W emulsion. The film passed through the printer twice: once for each filter used while shooting, incorporating the color through three immersions in dye baths: one for each color separation and another one for yellow.

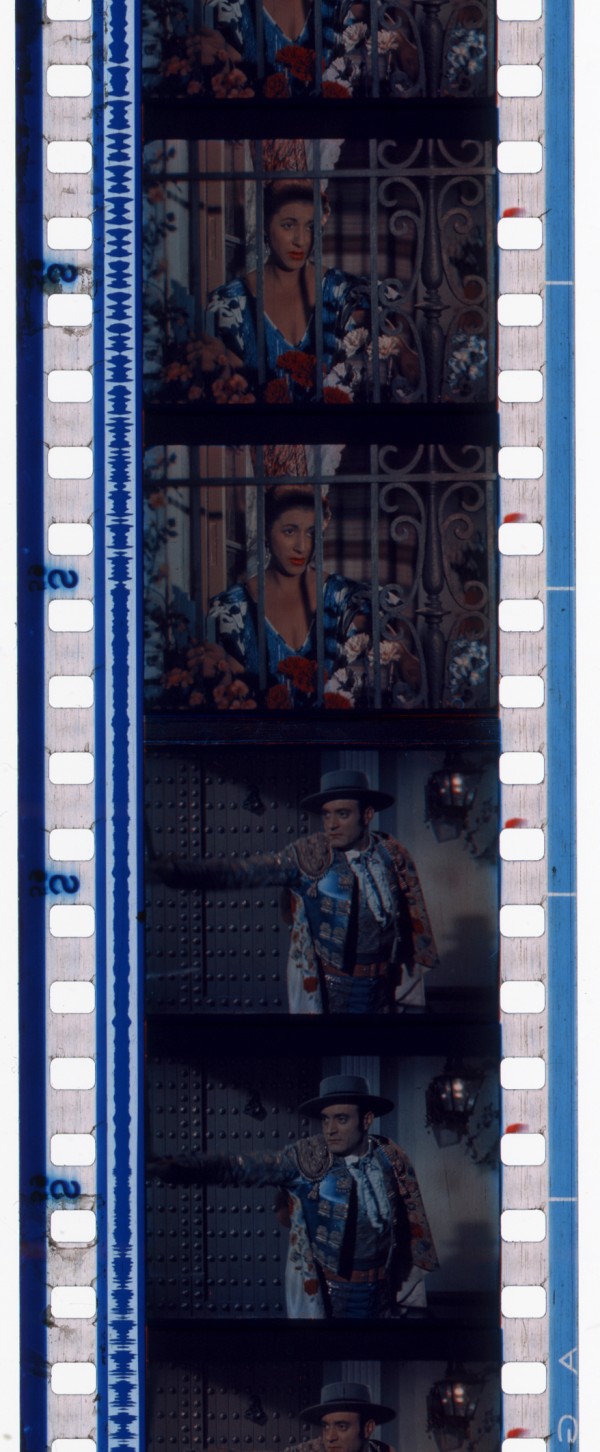

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings in blue text.

24 fps in projection. 48 fps during photography for the first two Cinefotocolor features; later features were photographed at 24 fps through a prism onto two negative films in synchronization.

1

Cinefotocolor was a two-color process consisting of red/orange and blue/green color records. The color yellow was incorporated by tinting (with a tartrazine solution) during the processing of each print, and could be adjusted according to the needs of the director and cinematographer. The process could not reproduce the full spectrum of colors.

Cinefotocolor

Variable-area optical sound. The soundtrack was printed in blue.

In the first version of the process, the B/W negative, registered two successive frames at 48 fps: one for each color record (red/orange and blue/green). Later, to avoid the temporal fringing effect, the camera was equipped with a prism behind the lens to capture two-color separations on separate strips of B/W 35mm film, each shooting at 24 fps.

Eastman Super-XX B/W panchromatic negative.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

History

In the decade between 1945 and 1955, 34 color films were made in Spain. More than half of them were shot and processed using a domestic color process called Cinefotocolor, conceived by Catalan engineer and industrialist Daniel Aragonés. It was one of several somewhat artisanal processes that attempted to break through in the post-war European film market (alongside those such as Dufaycolor, Gevacolor and Ferraniacolor), taking advantage of Germany’s wartime defeat – an outcome that undermined the prewar dominance of Agfacolor as the alternative to the costly American three-strip Technicolor. Aragonés’s initiative is best understood within the context of the forced self-sufficiency of the Spanish economy, a result of the country’s almost complete political isolation during the long, post-war, autocratic rule of General Franco.

During the early 1950s, the “españoladas” – those films produced under Franco’s dictatorship that forcedly promoted certain idealised and stereotypical Spanish characters and themes – played an important role in the debate on the exportability of Spanish cinema. If Carmen Sevilla was the muse of Gevacolor, Paquita Rico (Rumbo, 1949) and Lola Flores (La niña de la venta, 1951) became the two emerging international stars of Cinefotocolor. The best example of this folklorism, not without its own curious contradictions, was Debla, la virgen gitana (1951), which provided its star Paquita Rico with a personal triumph at the 1951 Cannes Film Festival.

As more directors and officials became aware of Italian Realism setting trends in European cinema, Debla’s success offered Daniel Aragonés the opportunity to market his Cinefotocolor process in France (where it was known as Realcolor) and to bet on a super US co-production. Muchachas de Bagdad / Babes in Bagdad (1951) was shot in Barcelona in a double-language version with an international cast. Its commercial failure was due not so much to the industrial approach it used, but rather to a governmental restructuring of the Spanish–American Cinematographic Agreement.

In total, 21 films were made using Cinefotocolor, and they illustrate both the aesthetics and the politics of the late 1940s Spain. Among the first were Emisora Films’ avant-garde En un rincón de España (1948) along with some hesitant attempts in collaboration with Catalonian producer Daniel Mangrané. Later, came two great successes: Duende y misterio del flamenco (1952), a visual encyclopedia of flamenco singing, and Doña Francisquita (1952), one of the best on-screen representations of the Zarzuela operatic tradition. Next came some experiments with the booming Catalan catholic nationalism, such as the animated feature Érase una vez… (1951). Then new ventures by Daniel Aragonés into, for example, the 3-D trend with El lago de los cisnes (1953). And finally, two B/W films with sequences in Cinefotocolor (Todo es posible en Granada, 1954 and Tres eran tres, 1954).

In 1990, at the Filmoteca Española, during a colloquium that followed the screening of a restored Cinefotocolor feature, the economic failure of Aragonés’ process was blamed on the release and rapid rise to dominance of Eastmancolor, ignoring the diplomatic, industrial and domestic political issues that existed in Spain between 1948 and 1953. Thus, the evolution of the Cinefotocolor process is essentially a metaphor of Spain’s isolation at the time and its dependence on US help – from the “red terror” refugees who find warm shelter in En un rincón de España (1948) to the fantastic journey from the Alhambra to New York’s Central Park in Todo es posible en Granada (1954), a ballet starring the dancer Antonio.

With the completion of a trilogy of films, consisting of two features in B/W and a last one, Tres eran tres (1954), in Cinefotocolor, Daniel Aragonés put an end to the process he had placed all his hopes on, and which for several years gave the (perhaps faded and blurry) illusion of innovation within the Spanish film industry.

Selected Filmography

Documentary with some fictional comedy skits that sought to map the genealogy of flamenco singing and dancing. Released as Flamenco in the US and restored in 1989 by Filmoteca Espñola from a subtitled copy from The Museum of Modern Art.

Documentary with some fictional comedy skits that sought to map the genealogy of flamenco singing and dancing. Released as Flamenco in the US and restored in 1989 by Filmoteca Espñola from a subtitled copy from The Museum of Modern Art.

A musical comedy. Released in France as La belle andalouse, with prints in Realcolor made by Labocolor.

A musical comedy. Released in France as La belle andalouse, with prints in Realcolor made by Labocolor.

Technology

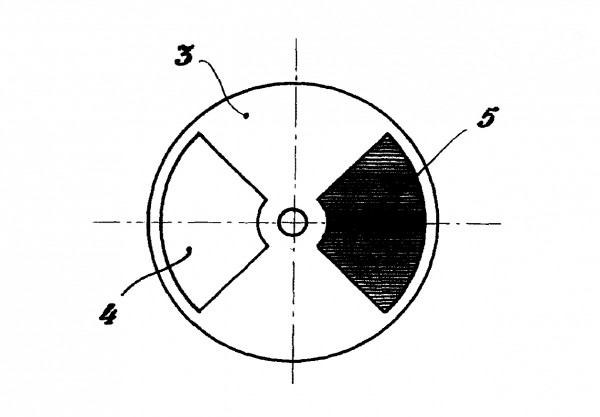

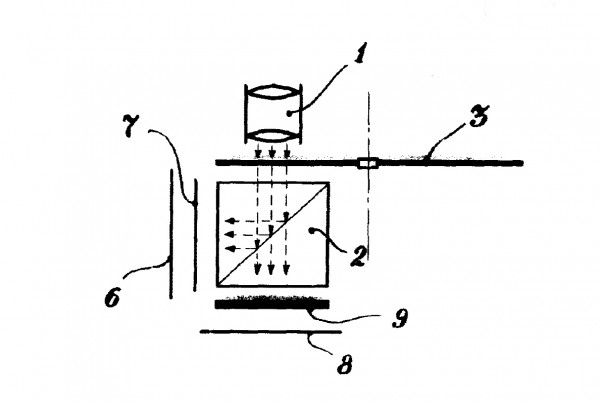

Cinefotocolor was a two-color subtractive process. It had two versions of image capture. The first two feature films were shot with a Super-Parvo camera with only one B/W negative running at 48 frames per second. The camera had a shutter with two windows, equipped with blue/green and red/orange filters, which imprinted odd and even frames in the color range defined by each of the filters.

The main advantage of the procedure was evidently economic. The main disadvantage, apart from the color calibration, was the temporal fringing effect, turning fast movements captured close to the camera into blurry red and blue trails on the image.

In the second version, the camera was equipped with two 35mm B/W film magazines that synchronously shot 24 images per second. The camera utilized a semi-reflective prism that divided the light into two beams of equal intensity, projecting them onto two windows equipped with the corresponding filters: blue/green and red/orange. This solved the fringing issue as long as the prism was correctly placed, but it introduced a new problem: the loss of light caused by the prism. However, those in charge claimed that the Eastman Super-XX B/W negative was sensitive enough to work with reasonable light levels.

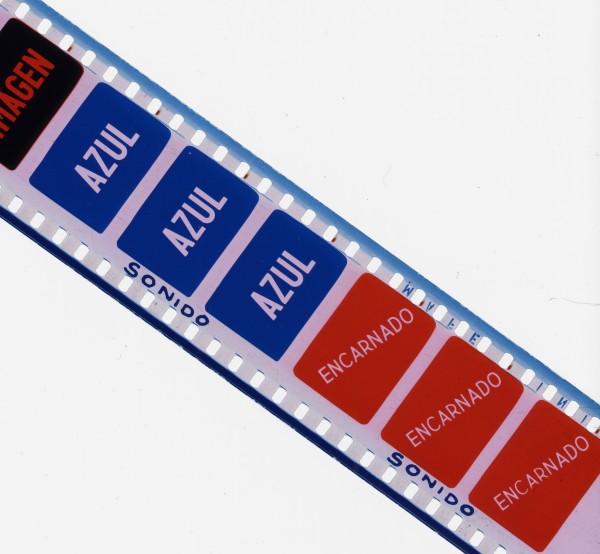

Film prints were also made on a B/W emulsion. The negative passed through the printer twice: once for each filter used while shooting. One color record was exposed through the base, and the other in contact with the surface of the emulsion. The colors were applied through three immersions in dye baths: one in a blue/green dye, one in red/orange, and another in yellow to compensate for the absence of the third primary color. The soundtrack was colored blue through dye-toning.

The spinning filter wheel used on the camera to capture alternating color negatives on the camera negative. This version of Cinefotocolor ran at 48 fps and was phased out in 1949.

Aragonés Puig, Daniel. 1949. Un procedimiento para la impresión de películas cinematográficas a tres colores. Spanish Patent ES186220, filed February 12, 1948, and issued January 3, 1949.

The second version of Cinefotocolor used a prism behind the lens to filter and capture two color records onto two strips of 35mm B/W negative. The camera had two 35mm magazines and ran at 24 fps.

Aragonés Puig, Daniel. 1949. Un procedimiento para la impresión de películas cinematográficas a tres colores. Spanish Patent ES186220, filed February 12, 1948, and issued January 3, 1949.

The leader on a 35mm Cinefotocolor print of the short Cante hondo (1952), directed by Edgar Neville. The component colors of red (encarnado) and blue (azul) can be seen clearly.

Filmoteca Española, Madrid, Spain.

References

Aguilar, Santiago (2022). Cinefotocolor, el color de la autarquía. Madrid: Filmoteca Española.

Berriatúa, Luciano & Isabel Benavides (2023). “La recreación del color de Érase una vez...”, Con A de Animación, 16: https://polipapers.upv.es/index.php/CAA/article/view/19130

Del Amo, Alfonso (1996). “El sistema bipack del Cinefotocolor”. In Inspección técnica de materiales en el archivo de una filmoteca, pp. 121–22. Madrid: Filmoteca Española.

Del Amo, Alfonso (2006). Clasificar para preservar. Madrid: Cineteca Nacional de México / Filmoteca Española.

Fernández Encinas, José Luis (1949). Técnica del cine en color. Madrid, Escuela Especial de Ingenieros Industriales. Edición electrónica no venal: Filmoteca Española (November 2006).

Herrero Herrezuelo, Miguel Ángel (2016). “El cinefotocolor.” Dissertation. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

Llinás, Francisco (ed.) (1989). Directores de fotografía del cine español. Madrid: Filmoteca Española.

Pagès, Maria (2019). “Els pioners de l’animació a Catalunya: La consolidació de la indústria de comunicació de masses a partir del film Érase una vez... (1950).” Dissertation. Universitat de Vic – Universitat Central de Catalunya.

Patents

Aragonés Puig, Daniel. 1946. Un procedimiento para la producción de películas cinematográficas en colores, Spanish Patent ES175605, filed October 26, 1946, and issued December, 1, 1946. https://consultas2.oepm.es/InvenesWeb/detalle?referencia=P0175605

Aragonés Puig, Daniel. 1948. Un procedimiento para la obtención de copias en colores de films cinematográficos, Spanish Patent ES182325, filed January 30, 1948, and issued April 1, 1948. https://consultas2.oepm.es/InvenesWeb/detalle?referencia=P0182325

Aragonés Puig, Daniel. 1949. Un procedimiento para la obtención de copias en colores de films cinematográficos, Spanish Patent ES187386, filed March 4, 1949, and issued May 1, 1949. https://consultas2.oepm.es/InvenesWeb/detalle?referencia=P0187386

Compare

Related entries

Author

Santiago Aguilar worked as a documentalist at the Filmoteca Española between 1985 and 1995 and has since continued to collaborate with the institution as a researcher. In collaboration with Felipe Cabrerizo, he has undertaken various works related to 20th century Spanish and South European cinema and popular culture. He has written books and articles on little known aspects of the history of Spanish cinema — for example, Operación Torremolinos: El cine español de superagentes (1965-1967) and Sagitario Films, oro nazi para el cine español (winner of the Muñoz Suay award from the Spanish Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences), both published in 2021, and Cinefotocolor, el color de la autarquía, published in 2022 — and gives classes in the Archive program of the Elías Querejeta Zine Eskola in San Sebastian, Spain.

Filmoteca Española.

Aguilar, Santiago (2024). “Cinefotocolor”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.

Margaux Chalançon