Film Explorer

Five 35mm prints were interlocked in projection to form one large image on a domed screen. Each print likely had a full aperture frame and was printed using Technicolor’s dye-transfer process.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer films were photographed on 35mm Technicolor Monopack film (Kodachrome). Five interlocked cameras photographed a larger mosaic image simultaneously.Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

Identification

History

The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer used five interlocked 35mm projectors to create an immersive training experience, and had its origins in Fred Waller’s Vitarama process. Vitarama was an attempt by the inventor to show motion pictures as a mosaic inside a concave screen to completely fill the viewer’s field of vision, creating a fully immersive visual experience. A modern-day equivalent would be an Omnimax-type screen.

The inventor Fred Waller started the process as a proposal for the presentation of a vision of the future of motion pictures, to be used at the 1939 New York World’s Fair in the Perisphere. It consisted of eleven interlocked 16mm Cine Kodak Special cameras for photography – and required eleven 16mm projectors to exhibit the process. Waller was a prolific inventor with hundreds of patents to his name, including a novel type of water skis called “Dolphin Akwa Skis”. He was also a motion-picture cameraman with considerable experience in silent film special effects, as well as a producer/director of many sound shorts for Paramount’s East Coast studio in Astoria, NY.

Eventually the World’s Fair idea was abandoned due to many complications and replaced with a multi-image slide show projected on the Perisphere dome called “The World of Tomorrow”.

However, demo test footage for Waller’s Vitarama happened to be seen in 1940 by several senior naval officers who were specialists in ballistics. They realized the Vitarama process had potential as a “virtual reality” (before the term was ever coined!) gunnery trainer, as America prepared to enter the Second World War.

At this time, gunnery training was a fairly crude affair that only taught servicemen the bare basics of artillery targeting. Some of the techniques were as rudimentary as trainees firing at a large flag being towed behind a plane – first from a static position on the ground, then graduating to firing from another plane in flight. Each gunner had their bullets dipped in a different colored dye, so each hit could be accounted for.

Unfortunately, this training process used up a massive amount of fuel, hardware, ammunition and war planes that could have been diverted to fight the enemy. A different way had to be found … and quickly.

Waller leapt to the Navy’s challenge. By his own account:

“...Within sixty hours I had the whole thing worked out. The answer came to me while shaving. The clue to the problem was to do it all backwards, to start at the point where the projectile struck the aircraft.”

The purpose of the new machine was to train gunners more efficiently under realistic battle conditions; to estimate quickly and accurately the range of a target; to track it and to estimate the correct point of aim when using non-computing sights. Waller and his team spent several months developing the apparatus, overcoming many complex problems.

His designs for the apparatus impressed the Army Air Corps and Navy officials enough to give him the use of four bombers and three pursuit planes for the making of a test film with his eleven-camera Vitarama prototype. By August 1940, Waller had a crude prototype trainer built, including a dummy gun and scoring mechanism. Officers of the Army Air Corps, the Navy and the Marines viewed the new test model in Waller’s West 55th Street labs in New York City and were impressed. Early in 1941, Waller received an order from the Navy for 31 trainers – with mass production to start immediately (without even seeing a full-scale prototype). Eventually a total of 75 trainers were built, several of these were taken to England. The cost to build each trainer was US$41,500 in 1941 (over US$860,000 in 2024).

Considering the plethora of moving parts, the record of reliability established by the trainer was remarkable and, perhaps, remains unparalleled in the history of analog motion-picture projection. Operating twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week – training more than one million servicemen in the US, Hawaii and England – not a single mechanism failed in-service and not one Waller Trainer had to be returned to the factory for overhaul.

Waller later recalled that he received over a thousand inquiries from servicemen to the effect of: “When are we going to see regular pictures like this!?” Waller’s account suggests that a strong commercial appetite for the rich cinematic experience, realized in later years with Cinerama, clearly already existed in the 1940s. Wartime experiences on the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer may well have helped to establish and reinforce this desire.

Selected Filmography

Technology

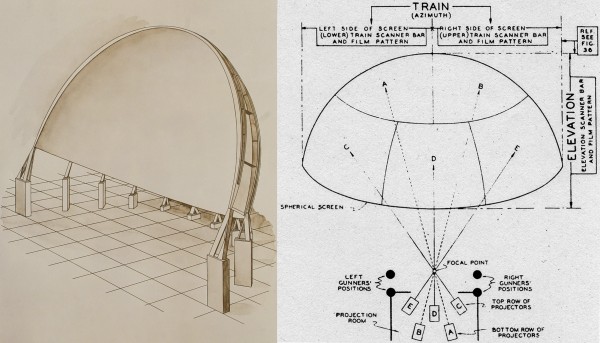

The final version of what came to be called the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer was improved and based on the use of a five-camera 35mm set up for photography, then standard 35mm Century projectors operating in synchronization for projection. The projectors (using standard 35mm nitrate film running at 24 frames per second) formed a composite mosaic image on a dome screen, beneath which four trainees sat at mock 50-caliber machine guns. Aiding the realism was the use of color film, photographed on 35mm Eastman Monopack (Kodachrome) film and printed using Technicolor’s dye-transfer process.

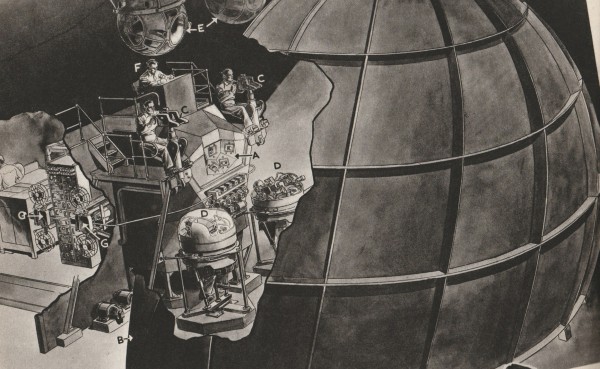

The trainees “fired” electronically at the images of attacking planes and would hear an electronic “beep-beep” through earphones, when they scored a hit. Up above, sat an instructor at a control console. The complex electronics of the scoring device (which filled a 30-ft-square room) involved four separate control films for each of the five projectors.

The gun stations recoiled when fired, just like a real turret gun, and the trainees wore headphones that played sounds of guns firing and aircraft noises (along with the scoring sound). The goal was to make the simulation as realistic as possible. When required, the projectors could freeze-frame, allowing instructors to intervene with any needed comments. Flammable nitrate film was used, but to prevent fires, each projector had a special cooling system to keep danger in check.

The gunners fired their “virtual” gun at projections on a screen and a photoelectric system scored their “hits”. It was estimated that one hour of training on the Waller device was the equivalent of ten hours of practice in the air. Calculations done after the war estimated that some 350,000 allied lives were saved due to the skills learned using the trainer.

The scoring mechanism took into account the movement of the attacking plane, along with the velocity of the gunner’s plane. This scoring system layout, which used four additional 35mm film elements, could determine a gunner’s hits and misses. The instructor would issue a “report card” of each gunner’s accuracy after each session.

Fred Waller adjusts the five-headed camera consisting of Bell and Howell Eyemos, with 1,000-ft film loads.

William Crist, “Movies Train Air Gunners”, Popular Science (September 1943).

Left: The dome screen.

Right: The five-projector mosaic screen panel layout.

Courtesy of David C. Strohmaier.

Front view of the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer.

Courtesy of David C. Strohmaier.

References

Caron, John P. (1998). Video interview recorded by David C. Strohmaier for Cinerama Adventure, David Strohmaier “Cinerama Adventure” collection, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States.

Crist, William (1943). “Movies Train Air Gunners”, Popular Science, September.

Erffmeyer, Thomas Edward (1985). “The History of Cinerama: A Study of Technological Innovation and Industrial Management”, Dissertation. Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, United States: pp. 27–32.

Strohmaier, David (n.d.). Waller Vitarama/Gunnery research files, David Strohmaier “Cinerama Adventure” collection, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States.

Technicolor Corporation (1943). “Release Shipments, 1924–1951”. Technicolor Corporate Archive, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Waller Vitarama/Gunnery research files, David Strohmaier “Cinerama Adventure” collection, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

David Strohmaier was a film history buff long before he graduated from the University of Iowa film school in the early 1970s and started his career at Warner Brothers. He has worked as a film and Avid editor on many TV movies, pilots, and series over the last 40 years, for major studios including The Walt Disney Company, MGM and 20th Century Fox. Special Projects have included editing two of the CircleVision films and EPCOT documentaries for Disney theme parks. Some of his more notable editing credits are Northern Exposure, Dangerous Minds, The Great Santini and three Alien Nation TV movies and several independent features. His most personal project to date, Cinerama Adventure, a feature documentary released by Warner Brothers on the complete history of the Cinerama widescreen era which marks David's debut as director and writer. He has served as an historical consultant to Paul Allen's Seattle Cinerama Theatre restoration project and also a continuing consultant to Pacific Theatre’s historic Cinerama Dome. David is working in cooperation with Pacific Theatres/Decurion Corp. (owners of Cinerama Inc. and its assets) in efforts to preserve and promote the Cinerama legacy as well as supervise the digital restorations of all the 3-panel Cinerama feature films and shorts. David has often been interviewed and contributor to websites like in70mm.com, trade publications like Film Technology, fan magazines including Cinema Retro, the web series “Trailers From Hell”, and podcasts such as “The Commentary Track” and “The Extras”. He is a member of the Film Editors Guild-Hollywood local 700, Theater Historical Society of America and also a member of the Academy’s Technology History Subcommittee.

Strohmaier, David C. (2024). “Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.