A system for projecting multiple moving images on a curved screen.

Film Explorer

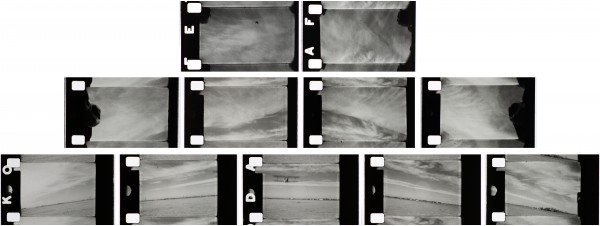

[Vitarama test footage] (c. 1937–39). The Vitarama format blended eleven 16mm films to create an immersive image on a curved screen.

Academy Film Archive, Hollywood, CA, United States.

Identification

Unknown

11

Some of the test footage was photographed on Kodachrome reversal film.

Much of the test footage that was shot and exhibited was silent, but there was experimentation with three-channel, sound-on-disc playback.

The frame size varied across each panel. Some were wider than others, presumably to account for some degree of image overlap during projection.

B/W or Kodachrome reversal film.

Standard 16mm Eastman Kodak edge markings.

History

Vitarama was a system for achieving panoramic film projection on a curved screen. Spearheaded by the inventor Fred Waller, it emerged amid the flurry of experimentation that took place between the 1920s and early 1940s with technologies that promised to enhance cinematic realism by more accurately replicating human sensory experience. This experimentation included work on photographic color, and synchronized and stereophonic sound, as well as systems for widescreen and stereoscopic exhibition. And it overlapped with developments in adjacent forms of art, media and technology such as, painting, architecture, radio, television, telephony and recorded sound (Belton, 1992; Crafton, 1997; Street & Yumibe, 2019; Rogers, 2019; Dienstfrey, 2024). Although the Vitarama process itself was employed only experimentally, it formed the basis for subsequent projection systems with greater reach –including the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer of the early 1940s and the Cinerama system that catalyzed the extensive embrace of widescreen cinema a decade later.

Waller first experimented with wide-angle views when working in Paramount’s special effects department in the mid-1920s, noting that “wide-angle pictures seemed to be more third dimensional than standard pictures” (Waller, 1993: p. 289). Years later, in 1937, he was approached by the architect Ralph Walker to help design the petroleum industry’s exhibit for the New York World’s Fair. Walker envisioned “a huge room, spherical in shape, on the walls of which would be thrown a constant stream of moving pictures from an entire battery of projectors” (Walker, 1953: p. 114). Waller had become convinced that stimulating a viewer’s peripheral vision was crucial to creating the illusion of depth in cinema – even more important than stereoscopy. With a conventional flat screen, however, doing so would require the projection area to expand beyond feasible proportions. Walker’s idea for a spherical projection surface supplied what Waller considered the key to making wide-angle projection a reality (Waller, 1993: pp. 289–90). Although this was a watershed discovery for Waller, Walker’s plan for an immersive projection space, and even a curved screen surface, echoed longstanding practices at world’s fairs as well as ideas that had been circulating in the avant-garde (Belton, 1992: pp. 85–9; Belton, 2004: p. 277; Rogers, 2019: pp. 135–9).

On September 14, 1937, Waller and Walker filed a patent for a motion picture theater that would accommodate projection onto a section of a sphere, with the aim to produce “the effect or illusion that the spectator is actually in and surrounded by the environment depicted” (Waller & Walker, 1937). The patent proposed achieving this with multiple projectors, which were to operate in conjunction with multi-track sound. Waller built a rig to yoke together and synchronize eleven 16mm cameras that he used to make test films, which included shots of people circulating around his home, as well as moving shots from his car. He also built a corresponding projection apparatus, which was initially installed in his home barn in Huntington, NY. David O. Selznick learned about this system in late 1937, during pre-production on Gone with the Wind (1939), and considered – but eventually gave up on – the prospect of using it to film and exhibit that film’s “burning of Atlanta” scene (Belton, 1992: p. 100; Rogers, 2019: pp. 58–62). Waller held demonstrations of the system both in his barn and in a rented office at 101 Park Avenue in New York City. After a research scientist from Eastman Kodak, John Capstaff, attended one of these and pointed out that reflection on the screen was degrading the image, Waller developed a new approach to screen construction, filing a second patent on June 14, 1938. Laurance Rockefeller, son of John D. Rockefeller Jr., attended a demonstration in late 1938 and had his interest piqued. The Vitarama Corporation was formed on November 3, 1938, “to develop the process”, with Waller, Laurance Rockefeller and Walker’s architectural firm signing on as stockholders (Waller, 1993: pp. 290–1: p. 291; Walker, 1953: p. 116).

Although Vitarama was not ultimately used for the petroleum exhibit, Waller did other related work for the New York World’s Fair. This included designing “a panoramic arrangement” of eleven projections of Kodachrome slides on a massive 187 ft x 22 ft (57m x 6.7m) curved and faceted screen for the Eastman Kodak exhibit as well as directing the “living mural” projected on the dome of the Perisphere (Waller, 1993: p. 291; Seldes & Garrison, 1939; Tuttle, 1940: p. 265; Walker, 1953: p. 116; Candee, 1954: p. 642). He also continued to develop Vitarama in a carriage house provided by Rockefeller on West 55th Street in New York City, with the intention of beginning production for a theatrical release to premiere at the Center Theatre in Rockefeller Center. After World War II erupted in Europe, however, he put the project on hold. In mid-1940 an old friend and expert in ballistics, who had seen some of the early demonstrations, approached Waller with the idea of converting Vitarama into a system to train machine gunners. Waller turned his attention to developing what became known as the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer (Waller 1946; Waller 1953; Waller 1993; Taylor 2013). After the war, Time Inc. hired him to develop equipment for showing slides on five-panel screens as a way of promoting Life Magazine – equipment that was subsequently borrowed by the U.S. State Department and used for propaganda in Germany and Japan. In November of 1946, with financing from entities and people including Time Inc., Rockefeller, and sound engineer Hazard Reeves, Waller formed the Cinerama Corporation in order, as he put it, to “promote the theatrical end of Vitarama” (Waller 1953, 126; Waller 1993; Reeves 1999). Cinerama, Inc. initially licensed the Vitarama design, and the Vitarama Corporation continued to develop and file patents for related technologies until Cinerama, Inc. acquired it in 1955 (“Cinerama Inc. Acquires Vitarama (Patents) From Fred Waller Estate”).

Selected Filmography

Surviving test shots include: Barn line up chart; Fred Waller's back yard; dolly through factory; static shot of factory; Kodachrome aerial footage over farmland; airfield as biplane flies over field; Waller's living room; Waller's back yard at night, men at campfire; early TV station activity; fire trucks drive through streets to a garage; nighttime fireworks display; Fred Waller close-up; nighttime aerial footage; drive through Oyster Bay, Long Island back road; Radio City Music Hall, dolly to Stage and Rockettes.

Surviving test shots include: Barn line up chart; Fred Waller's back yard; dolly through factory; static shot of factory; Kodachrome aerial footage over farmland; airfield as biplane flies over field; Waller's living room; Waller's back yard at night, men at campfire; early TV station activity; fire trucks drive through streets to a garage; nighttime fireworks display; Fred Waller close-up; nighttime aerial footage; drive through Oyster Bay, Long Island back road; Radio City Music Hall, dolly to Stage and Rockettes.

Technology

Vitarama was designed as a system for exhibiting moving images that would make it possible to stimulate viewers’ peripheral vision without requiring an immense screen. To do this, Fred Waller and Ralph Walker devised a method of projecting moving images onto a screen that was shaped as a section of a sphere. The initial patent proposed that this screen extend through arcs of approximately 180 degrees horizontally and 90 degrees vertically, thus taking the “form of a hollow quarter-sphere” (Waller & Walker 1937: p. 1). The screen that Waller first erected in his home barn was constructed as a section of a sphere curving 180 degrees horizontally and 75 degrees vertically – the sphere being, as Waller put it, “of a 6-ft radius with a continuous surface.” However, he noted that the opposing lens could be seen at the edges of the image, so he cut down the image by 7.5 degrees on each side, ultimately making pictures to be projected on a screen that curved 165 degrees horizontally and 75 degrees vertically (Waller, 1993: p. 291; Waller, 1953: p. 120).

In order to fill the relatively large, curved screen, the Vitarama system also called for what the patent described vaguely as “a plurality of projectors” showing “a plurality of films”. As Waller and Walker put it in the patent application, “when it is desired that the action proceeds from one screen area to another, a plurality of synchronously operated cameras may be used to make the separate films.” Moreover, in order to “avoid discontinuity of the complete image projected from the separate projectors”, they proposed using techniques such as masking to facilitate a slight overlapping of the projection areas (Waller & Walker, 1937: pp. 1–2). The system that Waller built and demonstrated in the late 1930s used a 16mm format for what Waller described as “the sake of economy, and because I could rely on my friends at Eastman Kodak to procure exactly what I needed,” including multiple matching lenses and monopack Kodachrome film. Waller determined that the use of 16mm film meant that he needed eleven projectors to create a suitable image, but he admitted that he “knew that if we ever switched to 35mm I could achieve the same mosaic effect with only five projectors” (Waller, 1953: pp. 120–1). Indeed, later adaptations of the Vitarama system that employed 35mm film, such as the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer and Cinerama (which also boasted an expanded frame size of six, rather than four, perforations in height on the 35mm filmstrip), used fewer projectors.

Waller built a rig assembling eleven 16mm cameras, driven by a shared motor, which he used to film test footage in both B/W and color. His initial exhibition installation included four connected projectors, but within nine months it had expanded to encompass eleven projectors. After John Capstaff of Eastman Kodak attended a demonstration of the system and noted that the image was being degraded due to internal reflection on the screen, Waller worked out what he described as “geometrical methods of building a screen with separate facets which would eliminate the internal reflection,” and he built a new curved screen with a louvred surface (Waller, 1993: pp. 290–3; Waller, 1938).

Waller and Walker’s initial patent called for “binaural sound effects” as a means “to increase the illusion of being in and surrounded by an environment”, clarifying that, “sounds accompanying the action of a picture will appear to the spectator to emanate from the source depicted” (Waller & Walker, 1937: p. 1). The system was being demonstrated without sound as late as 1940 (Reeves, 1953: p. 128). But Waller and his team experimented with three-track sound, recorded onto a single disc, with “each of the three grooves being supplied by sound from a separate source and the sound from each of the three pickups being amplified and fed directly to three loud speakers.” Waller contended that for “the first time we had seen a wide-angle, three-dimensional true perspective picture with realistic sound which enhanced the effect” (Waller, 1993: p. 293). And stereophonic sound would be a key feature of the Cinerama system that succeeded Vitarama (Reeves, 1999; Dienstfrey, 2024).

References

Belton, John (1992). Widescreen Cinema. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Belton, John (2004). “The Curved Screen”. Film History, 16:3: pp. 277–85.

Candee, Marjorie Dent (ed.) (1954). Current Biography: Who’s News and Why, 1953. New York: H. W. Wilson Company.

Variety (1955). “Cinerama Inc. Acquires Vitarama (Patents) From Fred Waller Estate”. Variety, (June 29): p. 7.

Crafton, Donald (1997). The Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound, 1926–1931. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Dienstfrey, Eric (2024). Making Stereo Fit: The History of a Disquieting Film Technology. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Reeves, Hazard E. (1953). “Adding the Sound to Cinerama”. In New Screen Techniques, Martin Quigley, Jr. (ed.), pp. 127–31. New York: Quigley Publishing Company.

Reeves, Hazard (1999). “This Is Cinerama”. Film History, 11:1: pp. 85–97.

Rogers, Ariel (2019). On the Screen: Displaying the Moving Image, 1926–1942. New York: Columbia University Press.

Seldes, Gilbert & Richard Garrison (1939). Your World of Tomorrow. New York: Rogers-Kellogg-Stillson, Inc.

Street, Sarah & Joshua Yumibe (2019). Chromatic Modernity: Color, Cinema, and Media of the 1920s. New York: Columbia University Press.

Taylor, Giles (2013). “A Military Use for Widescreen Cinema: Training the Body through Immersive Media”. The Velvet Light Trap, 72 (Fall): pp. 17–32.

Tuttle, Fordyce (1940). “Automatic Slide Projectors for the New York World’s Fair”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 34:3 (March): pp. 265–71.

Walker, Ralph (1953). “The Birth of an Idea”. In New Screen Techniques, Martin Quigley, Jr. (ed.), pp. 112–17. New York: Quigley Publishing Company.

Waller, Fred (1946). “The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 47:1 (July): pp. 73–87.

Waller, Fred (1953). “Cinerama Goes to War”. In New Screen Techniques, Martin Quigley, Jr. (ed.), pp. 118–26. New York: Quigley Publishing Company.

Waller, Fred (1993). “The Archeology of Cinerama”. Film History, 5:3 (Sep.): pp. 289–97.

Patents

Waller, Fred, and Ralph Walker. 1937. Motion Picture Theater. US Patent 2,280,206, filed Sept. 14, 1937, and issued April 21, 1942.

Waller, Fred. 1938. Screen for Picture Projection. US Patent 2,273,074, filed June 14, 1938, and issued February 17, 1942.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Ariel Rogers is an associate professor in the Department of Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University. Her research and teaching address the history and theory of cinema and related media, with a focus on movie technologies, new media, and spectatorship. She is the author of Cinematic Appeals: The Experience of New Movie Technologies (2013) and On the Screen: Displaying the Moving Image, 1926-1942 (2019) as well as essays on topics such as widescreen cinema, digital cinema, special effects, screen technologies, and virtual reality.

The author would like to thank James Layton, Crystal Kui and Film Atlas’s anonymous reviewers for their assistance with this entry; and David C. Strohmaier for providing access to and help with images and footage.

Rogers, Ariel (2024). “Vitarama”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.