Film Explorer

The images were recorded on the film transposed right/left within a single 16mm frame, featuring thicker frame lines. Linear polarizers in the projector lens and viewing glasses ensured proper encoding and cancellation of the images upon projection.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France

Identification

History

Though stereo still photography had been practiced since the era of the daguerreotype, and stereoscopic motion pictures successfully demonstrated in 1915, the 1947 introduction of the Stereo Realist 35mm stereo camera in the United States created an interest in 3-D still photography among amateurs. When loaded with Kodachrome, creating stereoscopic images in full color was easier than ever. Other camera manufacturers followed suit with their own versions in various still-camera film formats. Since 1938, Europe already had a similar camera in the Verascope f40 – produced by the French company Jules Richard.

In late 1951, 3-D came to the 16mm home movie maker with the announcement of the Nord 3-D “converter”, which could be used with a wide variety of 16mm movie cameras. A few months later, in the spring of 1952, Kern-Paillard introduced its own “Bolex Stereo” attachment. As with the Nord unit, it was a single-strip stereoscopic system, recording both left and right stereo images within a single 16mm frame, but was designed specifically for the Bolex camera, allowing for a greater degree of precision.

The initial system, intended for direct projection of the camera original on reversal film stock, included camera and projector lenses with the necessary adapters for mounting, and was priced at US$397.50. Polarized viewing goggles and aluminized projection screens were available for purchase separately. Later, Bolex introduced a close-up attachment featuring two sets of prisms in a circular housing, allowing them to be rotated into position in front of the stereo lens pair for two levels of closer convergence. The standard Bolex Stereo camera lens created a “stereo window” at 10 ft (3m) from the camera. Objects shot closer than this would appear in front of the screen and anything beyond that distance would appear behind the screen. When fitted with the close-up attachment, the standard setting was maintained by rotating the wheel inside the circular housing to expose two open apertures. Continued rotation of the wheel would place into position two sets of prisms which adjusted the convergence to effectively move the stereo window to two preset distances of 40 in and 24 in (0.25m & 0.61m) from the camera, allowing closer subjects to be framed properly while still appearing to float in front of the screen. With the open apertures and two sets of prisms, the close-up attachment provided only three distinct degrees of convergence, but in a far simpler accessory than one that would offer continuous adjustment.

In spite of the small format, the system was used in several professional capacities. In February 1953, a program entitled Triorama, comprising four short films photographed in Bolex Stereo, was presented publicly at the Rialto Theater in New York City. The great enlargement of the narrow projected image produced images which suffered by comparison to dual-strip 35mm 3-D and generated only a muted reaction. The system was used for various industrial and promotional films, however the primary use for the system was by advanced amateurs, with surviving examples relatively rare. The optics of the stereo attachment produced sharp images, and when filming was done with care to compose with depth in mind and within the parameters of the system, the 3-D was very effective.

Bolex Stereo was promoted as the future of movies, featuring an exciting, often modern-looking, subject projecting forth from the screen, while “yesterday’s” movies were illustrated with old-fashioned subjects, frequently positioned laterally to de-emphasize composition in the z-axis.

Bolex Stereo advertisement, 1953. American Cinematographer (July 1953): p. 335.

Bolex Stereo test film, photographed in Kodachrome, c. 1953. The amateur could choose color or B/W film depending upon preference.

Courtesy of John Harris, Carmel, CA, United States.

Selected Filmography

Industrial film photographed by Joe D. Price for the H.C. Price Company. Photographed on 16mm reversal stock and exhibited on reversal prints with sound.

Industrial film photographed by Joe D. Price for the H.C. Price Company. Photographed on 16mm reversal stock and exhibited on reversal prints with sound.

One of four short 16mm Bolex Stereo films presented under the omnibus heading Triorama. Photographed on 16mm reversal stock and exhibited on reversal prints with sound. Bolex Stereo features what is believed to be the first ever underwater 3-D motion picture footage. As of this writing, Bolex Stereo is the only surviving film from the Triorama program, and was included in the 2015 Blu-ray 3-D Rarities, presented by the 3-D Film Archive and released by Flicker Alley.

One of four short 16mm Bolex Stereo films presented under the omnibus heading Triorama. Photographed on 16mm reversal stock and exhibited on reversal prints with sound. Bolex Stereo features what is believed to be the first ever underwater 3-D motion picture footage. As of this writing, Bolex Stereo is the only surviving film from the Triorama program, and was included in the 2015 Blu-ray 3-D Rarities, presented by the 3-D Film Archive and released by Flicker Alley.

Promotional short for the Stone Container Plant photographed by Bernard Howard of Academy Film Productions Inc. Photographed on 16mm reversal stock and exhibited on reversal prints with sound.

Promotional short for the Stone Container Plant photographed by Bernard Howard of Academy Film Productions Inc. Photographed on 16mm reversal stock and exhibited on reversal prints with sound.

A home movie photographed as a test of the system for the British magazine Amateur Cine World. This film survives at the East Anglian Film Archive.

A home movie photographed as a test of the system for the British magazine Amateur Cine World. This film survives at the East Anglian Film Archive.

Technology

The Bolex Stereo system, designed primarily for amateurs, was used mainly with reversal films for projection of the camera original.

The lens featured twin lenses at the rear with parallel optical axes, and a separation of 5.3mm. A system of prisms widened the interaxial spacing to 64mm. The maximum aperture was f/2.8. The lenses were fixed focus, set at the hyperfocal setting of 10 ft, allowing for good definition from 5 ft to infinity at full aperture. Due to the design of the lens with relatively deep rear elements, the attachment could be used only on the non-reflex Bolex camera but not the later cameras with reflex finders.

Due to the smaller frame sizes, the image quality was roughly equivalent to that of 8mm photographed with high-quality optics. In the opinion of this author, the 3-D quality could be very good, especially when subjects were composed with the z-axis in mind. The results, while not traditionally immersive due to the narrow aspect ratio, possess an immediacy not possible in standard 2-D amateur motion pictures. Carefully filmed, the system was capable of the same quality of 3-D as later single strip lens attachments.

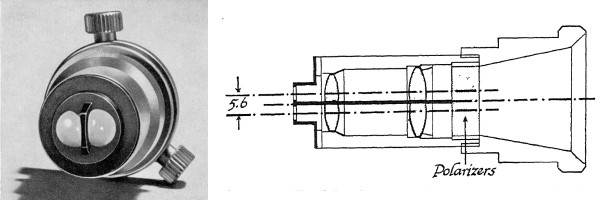

The 20mm focal length projection lens featured a duplex optical assembly with internal linear polarizers positioned at 135 degrees for the left-eye light path and 45 degrees for the right-eye light path to ensure compatibility with standard 'V-type' Polaroid viewing goggles.

The projection screens were mounted on tripod stands and were available in two sizes, 26 x 34 in and 38 x 50 in. They featured an aluminized surface which preserved the polarization of the left and right images. In addition, the screen surface included wide black matte masking to effectively hide the left and right “marginal parts” once the two images were aligned.

Left: Bolex H-16 Supreme with Bolex stereo lens and close-up adapter

Right: Bolex H16 Leader 16mm camera with stereo attachment and extension bracket. A stereo mask is also mounted on the Octameter viewfinder.

Hillary Hess. The Bolex Reporter 2:3 (Summer 1952): p. 14.

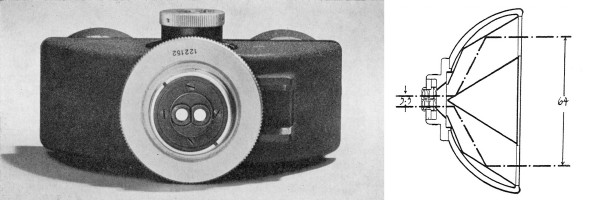

Left: Rear elements of the Bolex stereo lens.

Right: Schematic Diagram of the twin lens and “beam spreader” Bolex stereo attachment, illustrating the light path.

The Bolex Reporter 2:3 (Summer 1952): p. 14. / Millet, Eugene (1952). “Depth Effect in Motion Pictures”, The Bolex Reporter 3:1 (December 1952): p. 23.

Left: Rear elements of the Bolex stereo projection lens. The knurled knobs adjust focus and alignment.

Right: Schematic diagram of the Bolex stereo projection lens showing the position of the polarizers.

The Bolex Reporter 2:3 (Summer 1952): p. 12. / Millet, Eugene (1952). “Depth Effect in Motion Pictures”, The Bolex Reporter 3:1 (December 1952): p. 23.

The aluminized surface screen offered as part of the Bolex stereo system. Due to the splitting of the standard frame in order to record the left and right panels, the resulting image is taller than it is wide, a more “portrait” orientation than traditional motion pictures.

Bolex Stereo Movies [instruction manual] (Kern Paillard, 1952).

References

Anon. (1952). “Stereo Movies with the 16mm Bolex”, American Cinematographer (June): pp. 258–259.

Anon. (1952). “Bolex Stereo Movies… As You Live and Breathe”, The Bolex Reporter 2:3 (Summer): pp. 14–15.

Dewhurst, H. (1954). Introduction to 3-D Spatial Visualization. New York: MacMillan Publishing.

Howard, Bernard (1953). “3-D in Industrial Film Production”, American Cinematographer (August): pp. 374–375, 400–401.

Millet, Eugene (1952). “Depth Effect in Motion Pictures”, The Bolex Reporter 2:4 (December 1952).

Wildi, Ernst (1953). “How to Shoot 3-D Movies in 16-millimeter”, American Cinematographer (June): pp. 278–282.

Patents

None located.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Hillary Hess graduated from the Pennsylvania State University with a BA degree in Film, having studied film history and production. She was featured in the book A Thousand Cuts (2016) by Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph, profiling the world of film collectors. Also an avid stereoscopy enthusiast, she has created the Facebook groups “Vintage Stereo Slides” and “3-D on Film”, which has served as a clearing house for sharing images and information pertaining to the historical use of stereoscopy in photochemical formats. As part of the 3-D Film Archive Team, Hillary has contributed commentaries for the Blu-ray releases of A*P*E (1976), Those Redheads From Seattle (1953) and Jivaro (1954). She has also created vintage stereo slide presentations for the 3-D Rarities II and Robot Monster (1953) Blu-rays from the 3-D Film Archive.

Mike Ballew

Hess, Hillary (2024). “Bolex Stereo”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.