Film Explorer

Unidentified 16mm amateur film, c. 1930s. Kodachrome reversal film is recognizable by its high-contrast saturated images, black edges and orange edge print text.

Film Technology Frames Collection, Moving Image Department, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.

[Home Movie — Joan Crawford — Fishing & Hunting] (1940s). Kodachrome was a successful and widely-used home movie color process that allowed amateurs of the 1930s–1940s to photograph vivid colors on reversal film stock without the use of special camera or projector attachments. Hollywood actress Joan Crawford used 16mm Kodachrome film to document her friends and family in color.

Moving Image Department, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States

A 16mm Kodachrome reversal print of The African Queen (1951) – a film that was originally photographed using the three-color Technicolor process. Kodachrome reversal prints became an option for non-theatrical distribution of color feature productions from the late-1930s. Kodachrome’s heightened-saturation was a good match for reproducing Technicolor’s vibrant color palette on 16mm. This print is from 1951 and has a distinctive orange sulfide soundtrack.

Moving Image Department, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

History

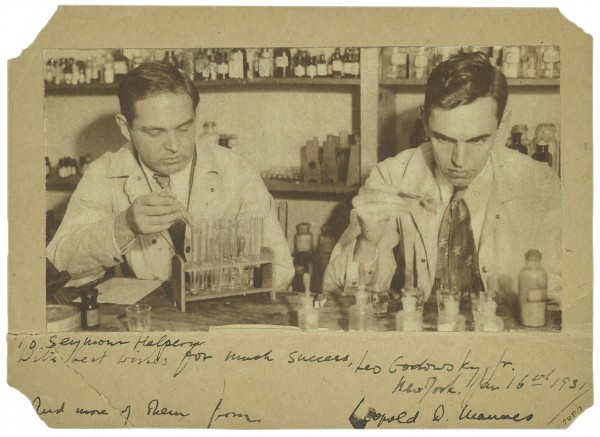

Kodachrome was invented by Leopold Mannes (1899–1964) and Leopold Godowsky Jr. (1900–1983). Mannes and Godowsky met, as teenagers, at a New York boarding school, the Riverdale Country School, in 1916. After seeing and being disappointed with the additive color in a four-color Prizma film – Our Navy (1918) – Godowsky recounted that, “we built a camera with three lenses and three films, one set for each color, and succeeded in superimposing all of those colors on a single photographic plate. After experiencing difficulty in aligning the three images, they “decided to switch from multiple lenses to multiple-layered film – in other words, from the optical approach [of additive color] to the chemical approach [of subtractive color]. We would try treating films with layers of emulsion instead” (Wechsberg, 1956).

C. E. K. Mees, head of research at Eastman Kodak, became aware of their work and “provided them with whatever equipment and other supplies [e.g., film coated with multiple emulsion layers] … they might need for their experiments” (Wechsberg, 1956). In the Spring of 1930, Mees visited them in their lab in New York City and invited them to relocate to Kodak Park in Rochester, where they began work on what would ultimately become Kodachrome.

Kodachrome was a three-emulsion monopack process. The basic idea for a multi-layer “monopack” emulsion had been patented by Leonard Troland, chief engineer at Technicolor, in 1931 (L. T. Troland, U.S. Patent 18,680, 1932). The Mannes and Godowsky patent was judged to interfere with Troland’s. As a result, Kodak entered into an agreement with Technicolor not to develop Kodachrome as a 35mm motion picture color process, but to limit it to 16mm, 8mm and 35mm still film (Hanson, 1981). In its various formats, Kodachrome was initially a camera reversal process, generating a direct positive image on a transparent base rather than a negative from which multiple prints could be produced.

From the earliest experiments involving multilayer film conducted by Dr. Rudolf Fischer and Dr. Hans Sigrist, there had been problems with multi-layer monopack films involving the wandering of color dyes from one layer to another during processing (Kukulski, 2014). The big breakthrough for Mannes and Godowsky’s experiments came when they perfected a “controlled diffusion process” – a way to control the penetration of color dyes in each layer of the emulsion and to keep them from spreading during printing, thus rendering a sharp image (Friedman, 1947). By 1933, Mannes and Godowsky had created a two-color process using dye-couplers introduced into the emulsion during the developing process. As Kodak made plans to release this new process, Mannes and Godowsky worked day and night to expand it to a three-color process, which was then put on the market on April 15, 1935. Kodachrome was initially available only in a 16mm reversal film format. But by May and September 1936, Kodachrome was also made available as an 8 mm format, and as 35mm still transparencies (Coe, 1978). The 8mm format became a standard gauge for home movies. It was most famously used by amateur photographer Abraham Zapruder to film the Kennedy assassination in Dallas on November 22, 1963. 35mm transparencies captured the explosion of the Hindenburg on May 6, 1937. In 1984, photojournalist Steve McCurry used Kodachrome 64 color slide film to memorialize Sharbat Gula as ‘The Afghan Girl’ on the cover of the National Geographic (Wilhelm, 2020).

Kodachrome film was designed for the use of amateur photographers – for those who shot film with non-professional cameras, but did not process it themselves. As Godowsky noted, “Mannes and I set about making a color film that the amateur photographer could use in his camera just as easily as he could use black and white film … the big stumbling block was the enormously difficult process of developing color film, and we finally decided that Eastman Kodak itself would have to handle that part of the operation. In other words, the customer would buy film … and then send it back to the factory, where Eastman would do the rest” (Wechsberg, 1956). Indeed, the development of Kodachrome film was so complicated that it had to be sent to Kodak for processing (Kukulski, 2014). Initially (1935–1938), due to the complexity of the controlled diffusion procedure, development involved a 28-step, three-and-a-half-hour process involving three different machines.(Coote, 1993). In 1938, Kodachrome processing changed from its original “controlled-diffusion bleach method” to the “selective re-exposure method” which reduced the number of steps involved in processing and provided greater color dye stability, extending the life of the colors over time (Cornwell-Clyne, 1951).

In 1938, when Kodak developed a process for duplicating Kodachrome film, Kodachrome emerged as an alternative for 35mm production in color. Norris Pope documents the increased use of 16mm Kodachrome by producers of commercial and educational films (Pope, 2016). Given its ease of use in the field, 16mm Kodachrome subsequently played an important part in the production of documentaries by the Office of War Information during World War II, including John Ford’s The Battle of Midway (1942), which won an Academy Award in the newly-created category of Best Documentary Feature, and William Wyler’s Memphis Belle (1944). Both were shot in Kodachrome and released in 35mm prints by Technicolor (see Technicolor Prints from 16mm Kodachrome and 35mm Monopack). After the war, Disney used 16mm Kodachrome to shoot eight films in a series of nature documentaries called True-Life Adventures (1948–1950) (Pope, 2016). The introduction of 35mm Eastmancolor in 1950 provided commercial filmmakers with a more professional format, returning 16mm Kodachrome to its former status as a premiere amateur filmmaking format. 16mm Kodachrome was used by a number of American avant-garde filmmakers, including Stan Brakhage (Wonder Ring, 1955; Creation, 1979), Joseph Cornell (Flushing Meadows, 1965), Michael Kuchar (Sins of the Fleshapods, 1965; Hold Me While I’m Naked, 1966), Jonas Mekas (Walden, 1968) and Ken Jacobs (Jonas Mekas in Kodachrome Days, 2009).

Kodachrome proved to be the source of Eastman Kodak’s greatest profits. It was, however, eventually eclipsed by digital photographic processes. Kodak ceased the production of Kodachrome film in 2009; the last Kodachrome film was processed in December 2010 at Dwayne’s Photo in Parsons, Kansas (Sulzberger, 2010). The format was memorialized in the 1973 Paul Simon song “Kodachrome”, for whom the word summons up “bright colors”, “the greens of summer” and “sunny days”.

Leopold Godowsky, Jr. (left) and Leopold Mannes in their lab, 1931.

Courtesy of John Belton.

A selection of Kodachrome packaging for 16mm film.

East Anglian Film Archive, Norwich, United Kingdom.

Faded test footage filmed by the Kodak Research Laboratories, early 1930s. Early versions of Kodachrome before c. 1938 are prone to color fading.

Film Technology Frames Collection, Moving Image Department, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.

Selected Filmography

Amateur film documenting some of London.

Amateur film documenting some of London.

Technology

As Mannes and Godowsky described it, “The [Kodachrome] emulsion … consists of three layers, each sensitized to one of the primary colors and separated from the adjacent layer by a thin coating of clear gelatin. The top layer of emulsion … is sensitive only to blue light, but it does transmit green and red light to the layers underneath. While it is sensitive to the blue, it also contains a yellow dye which prevents the blue light from passing through to the silver bromide grains below. The second or middle layer is sensitive to green and blue light, but as all blue is filtered out by the yellow dye just mentioned, we need to consider only its reaction to the green. Next to the film support is the bottom or third emulsion, which is sensitive to red and blue; but here again, the blue being stopped in the surface layer, this emulsion reacts to red only.

“Processing is carried out in continuous machines by a reversal process which converts … the images in all three layers to their corresponding positives. These three positive images are then differentially dyed … blue-green [cyan], magenta, and yellow. All silver is then removed from the film, after which it is washed and dried. The final positive accordingly carries a dye image only. From the three stages of processing described, we now have the three complementary colors in their respective layers.” (Mannes & Godowsky, 1935)

References

Coe, B. (1978). Colour Photography: The First Hundred Years, 1840–1940. London: Ash & Grant.

Collins, D. (1990). The Story of Kodak. New York: H.N. Abrams.

Coote, J. H. (1993). The Illustrated History of Colour Photography. Surbiton: Fountain.

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography. London: Chapman & Hall.

Friedman, Joseph S. (1947). History of Color Photography. Boston: The American Photographic Publishing Co.

Hanson, Jr., Wesley (1981). “The Evolution of Eastman Color Motion Picture Films”. Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers Journal , 90:9 (Sept.): pp. 791–794.

Heckman, Heather (2014). “Undervalued Stock: Eastman Color's Innovation & Diffusion, 1900–1957”. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin at Madison

Kukulski, Mike (2014). “A Brief History of Photography. Part 8: Kodachrome & Color Film” (June 24, 2014). https://notquiteinfocus.com/2014/06/24/a-brief-history-of-photography-part-8-kodachrome-color-film/

Le Guern, N. (2017). “Contribution of the European Kodak research laboratories to innovation strategy at Eastman Kodak”. PhD thesis, De Montfort University, Leicester.

Mannes, L. D. & L. Godowsky, Jr. (1935). “The Kodachrome Process for Amateur Cinematography in Natural Colors”. Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers Journal, 25:1 (July): pp. 65–68

Pope, Norris (2016). “Kodachrome and the Rise of 16mm Professional Film Production in America, 1938–1950”. Film History, 28:4: pp. 58–99.

Ryan, Roderick T. (1977). A History of Motion Picture Color Technology. London: Focal Press.

Sulzberger, A. G. (2010). “For Kodachrome Fans, Road Ends at Photo Lab in Kansas”. New York Times, Dec. 30, 2010.

Wechsberg, Joseph (1956). “Whistling in the Darkroom”. The New Yorker, Nov. 10, 1956.

Wilhelm, Henry (2020). “A History of Permanence in Traditional and Digital Color Photography”. In The Wilhelm Analog and Digital Color Print Materials Reference Collection, Henry Wilhelm, Carol Brower Wilhelm, Kabenla Armah & Barbara C. Stahl (eds). Wilhelm Imaging Research.

Patents

Mannes, Leopold D. & Leopold Godowsky, Jr. 1935. Color Photography, US Patent 1,997,493A, filed January 24, 1922, patented April 9, 1935.

Preceded by

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

John Belton is Professor Emeritus of English and Film at Rutgers University. He is editor of the Film and Culture series at Columbia University Press and was former Chair of the Board of Editors of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. He is the author of five books, including Widescreen Cinema (1992), winner of the 1993 Kraszna Krausz prize for books on the moving image, and American Cinema/American Culture (1994–2022), a textbook written to accompany the PBS series American Cinema. He earned his PhD in Classical Philology from Harvard University and specializes in film history and cultural studies. Belton has served on the National Film Preservation Board and as Chair of the Archival Papers and Historical Committee of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. In 2005/06, he was granted a Guggenheim Fellowship to pursue his study of the use of digital technology in the film industry.

Thanks to James Layton and Crystal Kui for their editorial guidance.

Belton, John (2024). “Kodachrome”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.