An amateur disk-based moving image technology invented in the late 1890s.

Film Explorer

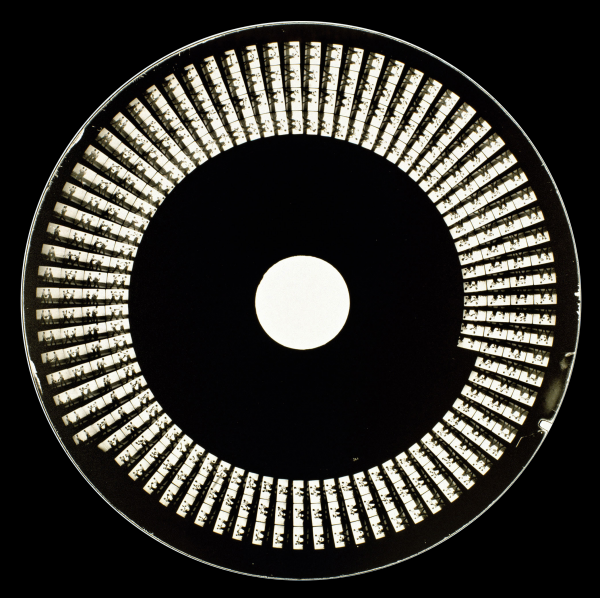

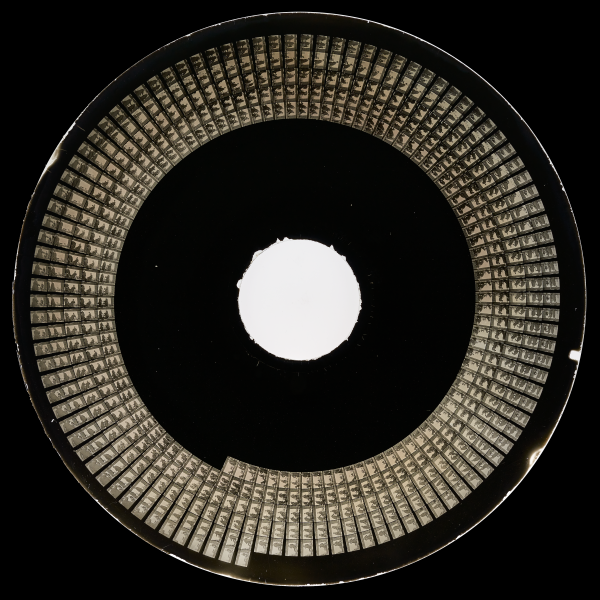

Kammatograph discs were available in two different configurations: a “300 pictures” glass disc, like this one, and a “500 pictures” disc with a smaller frame size. This disc, c. 1900, contains footage of two men boxing and is 273 frames long (with an approximate duration of 30 seconds). Each frame was slightly larger than a standard 16mm frame.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

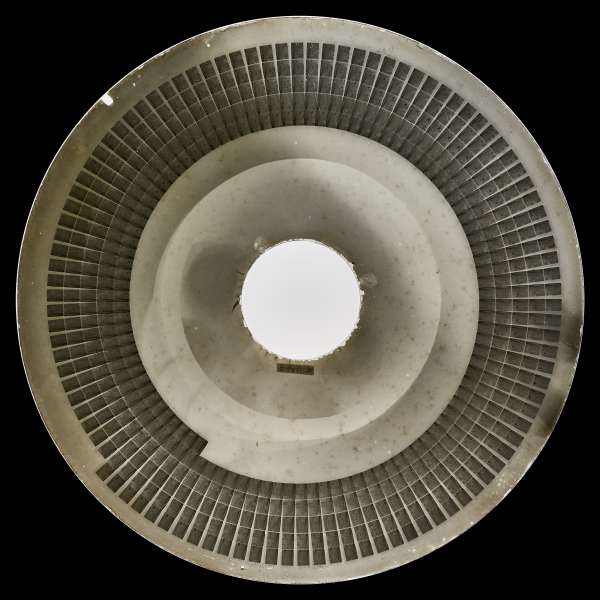

Disc 30.5cm (12 in) in diameter.

Approximately 12.5mm x 8.87mm (0.492 in x 0.349 in) for “300 picture” disc; approximately 9.14mm x 6.65mm (0.359 in x 0.262 in) for “500 picture” disc.

Approx.

Standard B/W orthochromatic emulsion for glass slides.

None

1

Disc 30.5cm (12 in) in diameter.

Approximately 12.5mm x 8.87mm (0.492 in x 0.349 in) for “300 picture” disc; approximately 9.14mm x 6.65mm (0.359 in x 0.262 in) for “500 picture” disc.

Standard B/W orthochromatic emulsion for glass slides.

History

The Kammatograph was a ‘filmless’ camera and projector invented in 1898 as an alternative to the celluloid-based cinema technology (UK 6515 of 1898). Instead of celluloid film, it recorded its images on a circular glass plate or disc, which was 12 in (30.5cm) in diameter. The disc shape makes the technology similar in design to nineteenth-century optical toys like the phenakistoscope. Depending on the specific camera model, the disc held either 500 smaller frames, or 300 larger frames (as quoted in the Kammatograph sales catalogue), although some modern historians suggest the smaller-frame discs may have actually contained between 550 and 600 images (Herbert, 2004; Lipton, 2021). Both models were presented with the same sized disc and the 300-frame version was also specifically recommended for shooting groups of people (the larger frame size allowed greater resolution). The images were photographed in a spiral fashion, akin to the arrangement of grooves on a vinyl record.

The Kammatograph’s inventor was the Bavarian-born Leonard Ulrich Kamm and his firm L. Kamm and Co. manufactured the apparatus at 27 Powell Street, London. Much like the film pioneer R. W. Paul, Kamm ran an engineering business and film equipment – lanterns, projectors, screens, arc lights, etc. – formed a part of a larger range of machines he designed and sold. These included the Zerograph, a telegraph machine that immediately transcribed the message it received (Bioscope, June 9, 1910: p. 7; Herbert, 1996). While Kamm produced films of notable sporting and historical events – such as Edward VII’s coronation procession – unlike Paul, his focus seems to have been more on the apparatus manufacturing side of the film business.

In a 1909 interview with the Kinematograph Weekly, Kamm said he designed the Kammatograph “for the use of the amateur photographer”. Keeping this amateur in mind, he “abandoned altogether the celluloid film and by substitution of an ordinary circular glass plate coated with emulsion”, achieved “better results at a smaller outlay.” (Kinematograph Weekly, 5 August 1909, 613). For this at-home use, the Kammatograph disc also circumvented one of the major dangers surrounding celluloid film – its flammability – which among other things had resulted in significant municipal regulation of film exhibitions in Britain. The glass-based technology was much safer in this regard. Finally, the cost of a Kammatograph disc was minimal compared to cinematograph film. Where a roll of raw film stock cost 20 shillings, plates for the Kammatograph (both negative and positive) cost 2 and a half shillings , with pre-printed positive plates at 3 and a half shillings. Therefore, Kamm saw an opportunity to cater to a home-viewing market (already familiar with handling photographs on glass plates) and make his machine as convenient for such use as possible. Indeed, as one news story – reprinted in Kamm’s catalogue – states, the glass-based technology would allow every mother to possess “animated photographs of baby in every conceivable pose” (Kammatograph Catalogue, 1901; Daily Mail, January 3, 1901: p. 3).

The Kammatograph was used by amateurs to record a variety of activities such as boxing matches, parades, historical events and processions, and many other scenes from daily life. The machine was used outside of Britain as well. In a 1909 interview, Kamm mentions that Madho Rao Scindia, the Maharaja of Gwalior in India, had bought a machine alongside “no end of plates” (Kinematograph Weekly, August 5, 1909: p. 615). Bioscope also suggests that the Kammatograph was used in Egypt by travelling showmen (Bioscope, June 15, 1916: pp. 1240–41). While not much more is known about the Maharaja’s possession of the discs or the Egyptian exhibitions, such stories suggest that there is scope for further investigation.

The Kammatograph machine is also part of the history of colour in cinema – though Kamm himself was not directly involved. Early colour film and photography pioneers William Norman Lascelles Davidson and Benjamin Jumeaux both purchased a Kammatograph and used it as part of their experiments in natural colour, animated photography. Jumeaux and Davidson added a disc with red and blue-green colour sections to their Kammatograph and used it to demonstrate two-colour-based moving image projection – notably at the 1903 Inventors’ Exhibition in Brighton. As Luke McKernan notes, Davidson and Jumeaux’s work “anticipates” the film pioneer George Albert Smith’s work with Kinemacolor. However, it is moot whether their Kammatograph experiments influenced Smith’s own disc-based colour system (McKernan, 2005, 210-211).

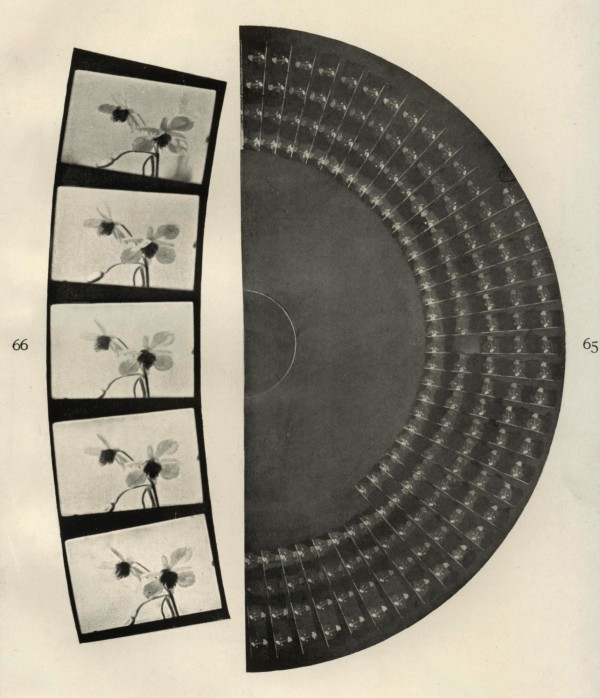

Perhaps the Kammatograph’s greatest success – and the reason behind most of the scholarly attention the machine has received – was its use for scientific demonstrations by the botanist Henderina ‘Rina’ Scott who chose the technology to record the growth of plants in a stop-motion fashion. In a 1903 paper based on her scientific demonstrations published in the Annals of Botany, Scott wrote,

“I at first experimented with a small film kinematograph, but the results were not satisfactory, as the machine was not suitable for making time exposures, and the makers were unwilling to help adapt their machine for scientific work. Also the life of the films when obtained was so short” [i.e. the film stock did not do well in the climate in which the exposures were made].

However, Scott expressed appreciation towards Kamm for “providing every possible help” in her scientific use of the machine (Scott, 1903: p. 772). All of this points to her as a film pioneer. Thus, the Kammatograph represents a part of the intertwining histories of gender, science and cinema (Bethel, 2013; Jones, 2017: pp. 165–7; Ayres, 2020: pp. 103–9; Long, 2021).

These instances of use notwithstanding, the Kammatograph did not commercially establish itself. Kamm himself acknowledged that the public was “not yet ready for animated pictures in their homes”, and his own film focus shifted to designing equipment for celluloid film (Kinematograph Weekly, August 5, 1909: p. 613). A major reason for the Kammatograph’s limited appeal was likely that a single plate ran for less than a minute. At 12 frames a second, a “500 picture” disc would run for a mere 45 seconds. This coupled with the fact that the glass disc made it impossible to edit the exposed images meant that the instrument had very limited use. The technology clearly left an impact as a form of scientific creativity though, as every time Kamm and his company were mentioned in the press there was always a nod to the innovative Kammatograph (Kinematograph Weekly, December 11, 1930: p. 51).

Interestingly, in later years, the press often discussed the Kammatograph as a moving image technology that existed “before the films” (Western Daily Press, December 11, 1932: p. 11). Such stories mythologise celluloid film as an advancement on ‘primitive’ moving image technologies. As noted here though, the Kammatograph was developed contemporaneously with celluloid-based moving image technologies. Furthermore, for certain purposes – like Rina Scott’s – the glass disc was better-suited than perishable (and potentially flammable) celluloid. One might even see the glass-disc technology as a precursor to 16mm, 9.5mm and other later-developed non-flammable film formats, that were designed specifically for non-theatrical exhibition. The Kammatograph is a reminder that the film and other forms of moving image media emerged in what Andre Gaudreault refers to as the “culture broth” of visual media, technologies and viewing practices (Gaudreault, 2012: p. 16). While not literally the ‘film’ of film history, the Kammatograph was part of an environment where people attempted to make moving images valuable (and sustainable) for different modes of pleasure and learning. The technology’s importance to film and media, technological and scientific, and gender-based histories should be valued in this regard.

Image of Henderina ‘Rina’ Scott’s Kammatograph Glass Plate from her article “On the Movements of the Flowers of Sparmannia africana, and their Demonstration by means of the Kinematograph”.

Scott, Rina (1903). ‘On the Movements of the Flowers of Sparmannia africana, and their Demonstration by means of the Kinematograph’. Annals of Botany, 17:4: p. 778.

Selected Filmography

A stop-motion timelapse study of the growth of the Sparmannia africana (African Hemp) plant. This film is not known to survive.

A stop-motion timelapse study of the growth of the Sparmannia africana (African Hemp) plant. This film is not known to survive.

This “300 picture” disc of two men boxing is in the collection of the Cinémathèque française in Paris, France.

This “300 picture” disc of two men boxing is in the collection of the Cinémathèque française in Paris, France.

Twelve Kammatograph films preserved by the George Eastman Museum. Subjects include: Girl jumping/dancing around, Boys on school playground, Mother playing with her children, Three men drinking whiskey outside, People sledding, Kids feeding a swan by a pond, People on city street, walking and riding bikes, Man and boy on horse and buggy, Three girls on busy street corner, Family socializing outside, Three women and boy walking on dirt road and Parade. The George Eastman Museum has a total of 58 Kammatograph discs in its collection, both negatives and prints.

Twelve Kammatograph films preserved by the George Eastman Museum. Subjects include: Girl jumping/dancing around, Boys on school playground, Mother playing with her children, Three men drinking whiskey outside, People sledding, Kids feeding a swan by a pond, People on city street, walking and riding bikes, Man and boy on horse and buggy, Three girls on busy street corner, Family socializing outside, Three women and boy walking on dirt road and Parade. The George Eastman Museum has a total of 58 Kammatograph discs in its collection, both negatives and prints.

The National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, UK, holds four Kammatograph discs; three prints and one negative. The negative disc contains footage of a child. The contents of the other discs are unknown.

The National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, UK, holds four Kammatograph discs; three prints and one negative. The negative disc contains footage of a child. The contents of the other discs are unknown.

Technology

The Kammatograph was both a camera and a projector. It used a glass disc of 12 in (30.5cm) in diameter and recorded between 350 and 550 images on it. The frames were set in a spiral arrangement, and the disc was rotated by a hand-crank. Inside the camera, the disc was mounted in a circular metal frame with notches around its edge. A drunken screw engaged these notches to rotate the disc intermittently. The disc itself rode on a helical screw to keep the frames aligned with the lens and along the optical axis. When shooting, the disc was exposed to light through the camera lens one frame at a time. The disc was then processed as a negative in the same way as any photographic lantern slide or other glass plate at the time, and contact printed onto another glass disc to make a positive projection copy.

For projection, as Kamm’s catalogue suggests, the “transparency, or positive plate, is placed in the camera in the same manner as was done with the negative” when recording the images. However, “with the emulsioned side away from the lens”. The Kammatograph was then placed “6–7 inches” (15.2–17.8cm) away from an optical lantern (the light source) to obtain the projection on screen. Essentially, the Kammatograph was placed in the reverse position to the one used to record an image and the lantern illuminated the disc via the lens – from the side of machine that faced the subject being recorded – and the lens on the other side was used to magnify the image. According to the catalogue, “if the apparatus is placed, say 20 ft. [6.1m] from the screen, a picture of about 6 ft. [1.83m] square will appear and a clear detail be given” (Kammatograph Catalogue, 1901: p. 9).

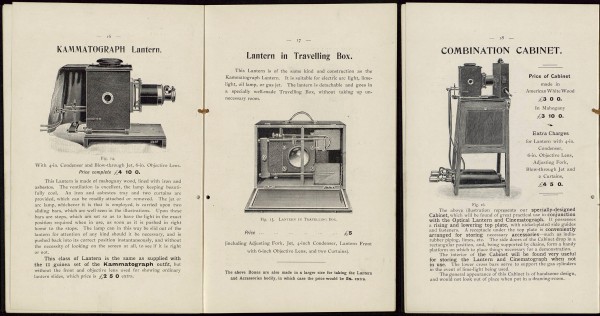

The catalogue advised the purchase of a specific lantern to go with the camera (though the technology appears to be compatible with any lantern projector) (Kammatograph Catalogue, 1901: pp. 16–17; St. Andrews Citizen, July 21, 1900: p. 2). Furthermore, the catalogue also advertised a ‘Combination Cabinet’ which among other things acted as a neat platform for the lantern and the Kammatograph. The image in the catalogue suggests that both could be fixed neatly onto the stand, making the whole contraption a sturdy projection machine (Kammatograph Catalogue, 1901: p.18).

The Kammatograph camera with the lens to the front. The viewfinder and the crank can be seen on the right-hand side.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

The Kammatograph camera from the side as seen by the photographer. The camera could be converted into a projector. The magnification lens visible in the image was used to magnify the images during projection.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

The inner workings of the Kammatograph camera. On the side of the machine is a small viewfinder and the disc would be exposed through the small lens mounted inside the box. The circular hand crank moved the disc. The notched circular metal frame, that held and advanced the disc, is partially visible.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Kammatograph Lantern (projector lamp house) and its travelling case (left). The ‘Combination Cabinet’ showing how the Kammatograph and the lantern could be combined to project the discs (right).

Kammatograph Catalogue, 1901: pp. 16–18.

References

Ayres, Peter (2000). Women in Natural Sciences in Edwardian Britain. London: Palgrave McMillan.

Bethel, Amy (2013). “Henderina Victoria Scott”. In Women Film Pioneers Project, Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal & Monica Dall’Asta (eds). New York: Columbia University Libraries. https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/ccp-henderina-victoria-scott/ (accessed August 13, 2024).

Ciné-Resources (n.d.). “Kammatograph Patent: Accessories and Specialties or Kammatograph Catalogue. London: L. Kamm and Co, 1901”. http://www.cineressources.net/consultationPdf/web/o000/299.pdf (accessed August 13, 2024).

Gaudreault, Andre (2012). “The Culture Broth and the Froth of Cultures”. In A Companion to Early Cinema, Andre Gaudreault, Nicholas Dulac & Santiago Hidalgo (eds), pp. 15–31. Chichester: John Wiley.

Herbert, Stephen (1996). “Leonard Ulrich Kamm” in Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema. https://www.victorian-cinema.net/kamm (accessed August 13, 2024).

Herbert, Stephen (2004). In The Encyclopaedia of Early Cinema, Richard Abel (ed.), p. 354. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

Jones, Clair G. (2017). “’All your dreadful scientific things’: women, science and education in the years around 1900”. History of Education, 46:2: pp. 162–75. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0046760X.2016.1273406 (accessed August 13, 2024).

Lenny Lipton (2021), The Cinema in Flux: The Evolution of Motion Picture Technology from the Magic Lantern to the Digital Era, p. 469. Berlin, New York: Springer.

Long, Max (2021). “A ‘Secrets’ Pioneer? Rina Scott’s early films”. Secrets of Nature: Science and natural history films in interwar Britain. https://secrets-of-nature.co.uk/2021/04/27/a-secrets-pioneer-rina-scott/ (accessed August 13, 2024).

McKernan, Luke (2005). “The Brighton School and the Quest for Natural Colour”. In Visual Delights Two, Vanessa Toulman & Simon Popple (eds), pp. 205–18. Eastleigh: John Libbey.

Scott, Rina (1903). “On the Movements of the Flowers of Sparmannia africana, and their Demonstration by means of the Kinematograph”. Annals of Botany , 17:4: pp. 761–78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43235237.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A31c944f5a3b8ce66d24e72a6bf21490e&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1 (accessed August 13, 2024).

Patents

Kamm, Leo Ulrich. 1898. Improvements in Apparatus for Photographing and Exhibiting Cinematographic Pictures, GB Patent UK6515 of 1898.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Dr. Anushrut Ramakrishnan Agrwaal is an Associate Lecturer at the Department of Film Studies, University of St Andrews, whose research interests include nineteenth- and twentieth-century British educational and visual culture, non-theatrical film, film technologies, science and cinema and colonial cinema.

I would like to thank the Ciné-resources Website, The British Newspaper Archive and Bill Douglas Cinema Museum for their resources; the anonymous reviewers and James Layton and Crystal Kui for their patience and guidance.

Ramakrishnan Agrwaal, Anushrut (2024). “Kammatograph”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.