An additive two-colour process invented in the United Kingdom and exhibited across the world. The first commercially and technically successful motion picture natural colour process.

Film Explorer

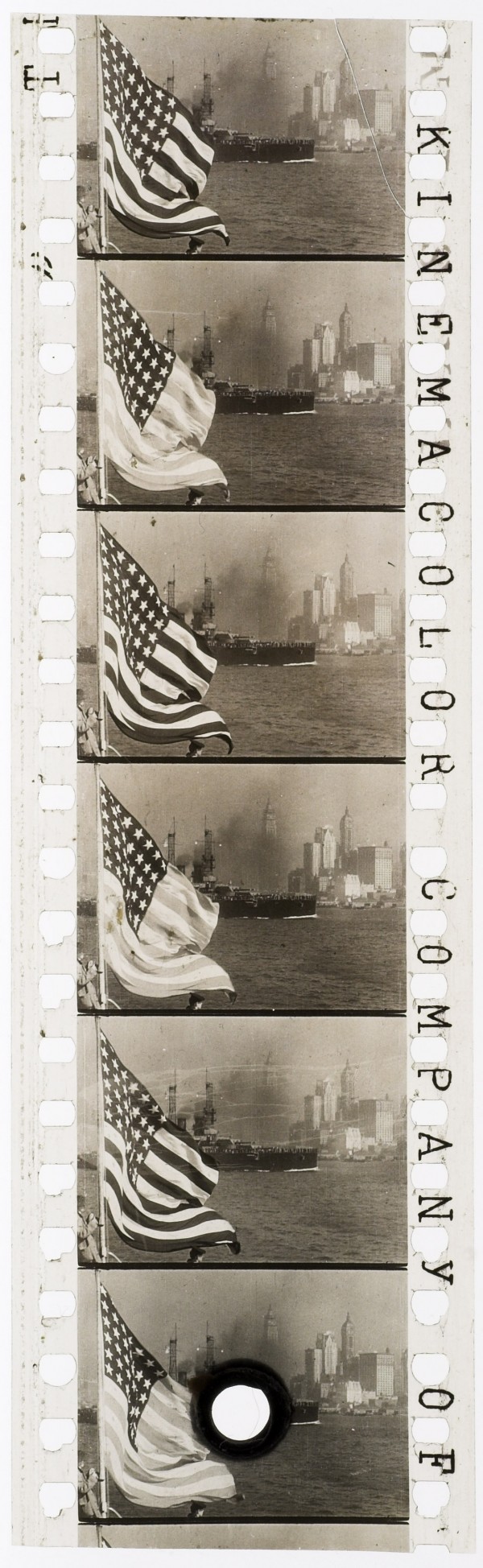

Unidentified Kinemacolor film shot in New York City. The difference in tonal values between the two frames can clearly be seen in the stripes of the flag.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Adjacent ‘red’ and ‘green’ frames from the Kinemacolor Company of America’s production The Scarlet Letter (1913), based on the novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne. The difference in tonal values between the two frames can be seen in the tunics of the two soldiers to the left of the frame.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

Unknown

B/W

Some American prints have the words “THE KINEMACOLOR COMPANY OF AMERICA”.

1

Two-colour process. Colour appeared only in projection through use of a rotating red/green filter wheel, similar to that used for taking the film.

For UK releases: Charles Urban [signature] followed by KINEMACOLOR or KINEMACOLOR PATENTS. For US releases: KINEMACOLOR AMERICA with filter wheel icon.

Unknown

B/W, panchromatic.

Unknown

History

Kinemacolor was the world’s first successful natural colour motion picture process. Between 1908 and 1917 it was exhibited across every continent, greatly influencing perceptions of cinema, as much through its subject matter as its depiction of colour. Its technical limitations – limited colour range, reported audience eye-strain, fringing that accompanied lateral motion – were outweighed by the exoticism of its travel subjects and the prestige of its actualities, which featured British royalty. Kinemacolor brought new audiences to cinema and increased appreciation of what cinema might achieve. Its success inspired efforts to develop more accurate colour systems, leading ultimately to three-strip Technicolor.

The two-colour additive process was invented by British filmmaker and film laboratory owner George Albert Smith, based in Hove, near Brighton, East Sussex. Smith undertook the project in 1902 at the behest of Anglo-American film producer Charles Urban, who had been funding the development of the three-colour process of Edward Turner, which had failed to work in projection. Smith concluded that a three-colour mechanical solution was unfeasible, but (probably inspired by the experimental work of W.N.L. Davidson and Benjamin Jumeaux, which he had processed at his Hove studio) he discovered that he could use just two primary complementary colours, red and green, to yield a satisfactory colour record. He patented his solution in 1906 (McKernan, 2005: pp. 207–9).

Kinemacolor was exploited through exhibition rights, the sale of international patent rights, and exclusive use of Kinemacolor apparatus and films. Kinemacolor was shown in many more countries than those few countries for which patent rights were sold, and there were mixed fortunes for those territories that paid handsomely for those rights. The Kinemacolor Company of America, formed in February 1910 (over which Urban had limited influence before it became independent of him the following year), flourished for a while, obtaining a licence to operate from the Motion Picture Patents Company, the only new company to join the trust following its formation in September 1908. Studios for fiction films were rented in 1912 in Whitestone, Long Island, NY, and at 4500 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, but the latter had closed within a year (Bowser, 1990: pp. 229–32). Insufficient numbers of new films, combined with the reluctance of exhibitors to install specialist equipment, led to the company’s failure before World War I. A French venture, initiated by Raleigh et Robert, copied the British strategy of having a dedicated film company, Kinemacolor de France, and showcase theatre, the Théâtre Edouard VII in Paris. But the company flotation failed, and the theatre was a financial disaster that helped bring down Kinemacolor. However, in Japan, where Kinemacolor was controlled by the Tenkatsu film combine, local exhibition and production flourished (McKernan, 2013: pp. 109–15). Other countries exhibited Kinemacolor but did not engage in local production. In Italy there were Kinemacolor films produced by Comerio Films c.1912–14, but it is unclear whether it did so under licence (Gervasio, 2017: pp. 38–9).

Over a three-year period, from April 1911 to March 1914, Kinemacolor in Britain – having started out in March 1909 with £30,000 in capital – showed receipts of £297,048 and expenditure of £260,070, demonstrating a potentially productive and profitable business, but at a high cost (McKernan, 2013: pp. 122–3). Though in theory it was in competition with the artificial, stencil-coloured systems of Gaumont and Pathé, in practice the films of the latter were shown in conventional cinemas, while Kinemacolor films were sold to a different market, one that was predominantly theatre-based and able to attract audiences willing pay higher prices for a luxury entertainment. Rival natural colour systems, notably Gaumont’s three-colour Chronochrome, first shown in November 1912, could boast a more naturalistic color rendition than Kinemacolor, but was not shown widely enough to be a commercial threat (McKernan, 2013: pp. 98–9).

What brought down Kinemacolor, however, was a patent suit from a rival film colour system that was seen by almost no-one. It came from William Friese Greene, British inventor of the Biocolour system, who sued the Natural Colour Kinematograph Company for infringement of his supposed patent rights. Though Charles Urban won the initial case (December, 1913), he lost on appeal (March, 1914), the judge damning Kinemacolor for failing to reproduce the blue that its patent said that it could (McKernan, 2013: pp. 118–22). This outcome did not prevent further Kinemacolor production, but destroyed its exclusivity. Urban liquidated the Natural Color Kinematograph Company and formed a new production company, Colorfilms, but future production plans were stymied by the onset of World War I. Urban lobbied to have Kinemacolor used in British official propaganda films, but succeeded no further than having some colour sequences in the documentary feature Britain Prepared (1915), which were dropped for its international release version (McKernan, 2002: p. 370). Kinemacolor production and exhibition worldwide had mostly ceased by 1914, though films using the system continued to be made and exhibited in Japan until 1917. The last film to use Kinemacolor was the Japanese fiction film Saiyûki zokuhen (1917) (Komatsu, 1995: p. 79).

Urban moved his diverse businesses to the United States following the war under an umbrella company Urban Motion Picture Industries, formed in 1920 and located at Irvington-on-Hudson, NY (McKernan, 2013: p. 178). He attempted to revive Kinemacolor through a projection system devised in 1915 by engineer Henry Joy, with an improved intermittent movement that halved the time interval between taking red and green records, entitled Kinekrom (Thomas, 1969: p. 35). Lacking the capital to produce new Kinekrom films, Urban made use of his Kinemacolor library for a trial public screening at the Wurlitzer Fine Arts Hall, New York, in November 1916, followed by a short run at Samuel Rothafel’s Capitol Theatre over June and July in 1924. The collapse of Urban Motion Picture Industries in 1925 brought an end to Kinekrom, and the Kinemacolor library of films was largely lost, either melted down, or passed on to film libraries as oddly slow-moving B/W stock footage (McKernan, 2013: pp. 188–96).

Engineers who had worked for Urban in London, or with the Kinemacolor Company of America, worked on improvements based on Kinemacolor’s principles, among them William Crespinel, who would devise the two-colour subtractive colour system Cinecolor, and William Francis Fox, who experimented with both additive and subtractive colour systems. American inventor William Van Doren Kelley, having experimented with a four-colour rotating disc additive system similar to Kinemacolor, turned to subtractive solutions and produced (with Charles Raleigh, of Raleigh et Robert, and Kinemacolor de France) two-colour Prizma Color which enjoyed some success in the early 1920s. Also keeping an eye on Kinemacolor, during his early colour development work, was Herbert Kalmus, whose subtractive three-strip Technicolor would consign Kinemacolor, and all other additive colour systems, apart from television, to the history books (McKernan, 2013: pp. 188–9, 196).

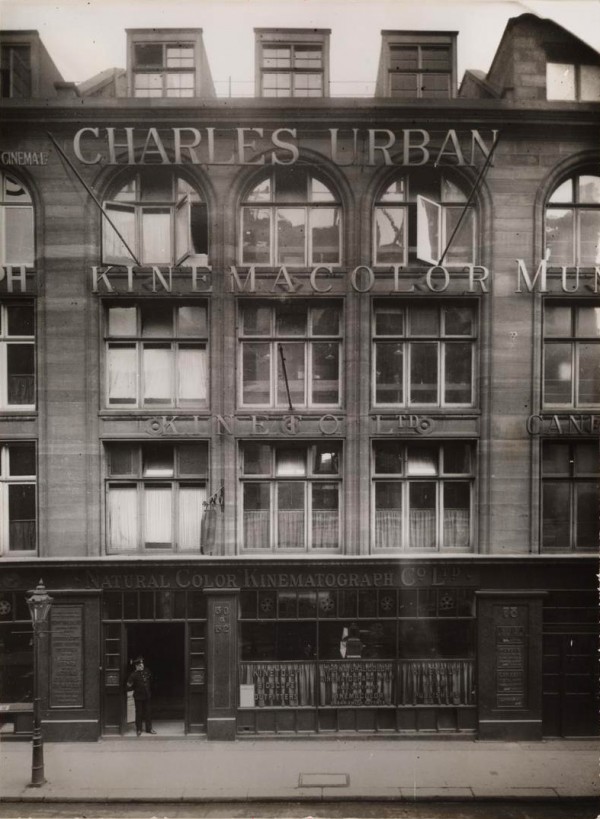

Kinemacolor House, London, c. 1910.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

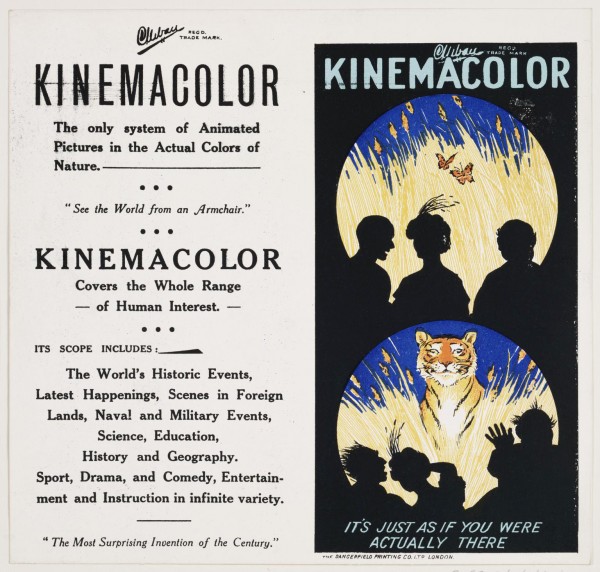

British Kinemcolor advertisement, c.1911.

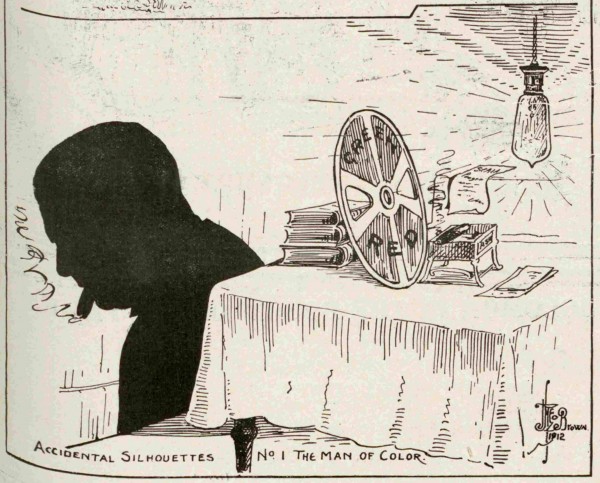

Cartoon by Theodore Brown of Charles Urban silhouetted through a Kinemacolor filter wheel.

“Accidental Silhouettes No. 1: The Man of Color”, The Bioscope (February 22, 1912). p. 509.

Cover of a brochure promoting the ill-fated Parisian Kinemacolor theatre, the Théâtre Edouard VII, December 1913.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

From a brochure advertising Kinemacolor feature film The World, the Flesh and the Devil (UK 1914).

Advertisement for the Kinemacolor shows at London’s Scala Theatre, which was used as a showcase theatre for Kinemacolor.

Advertisement for the Kinemacolor shows at London’s Scala Theatre, which was used as a showcase theatre for Kinemacolor.

Selected Filmography

Feature-length documentary. Propaganda film demonstrating Britain’s military preparedness. B/W film with Kinemacolor sequences for British release version only. Extant material: B/W film in Imperial War Museums, London, UK; some Kinemacolor sequences at John E. Allen Inc, Newfoundland, PA; nitrate originals now held by the US Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA.).

Feature-length documentary. Propaganda film demonstrating Britain’s military preparedness. B/W film with Kinemacolor sequences for British release version only. Extant material: B/W film in Imperial War Museums, London, UK; some Kinemacolor sequences at John E. Allen Inc, Newfoundland, PA; nitrate originals now held by the US Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA.).

Feature film based on the stage production of Thomas Dixon’s novel of the same name; production abandoned and film remade in B/W by D. W. Griffith as The Birth of a Nation. Lost film.

Feature film based on the stage production of Thomas Dixon’s novel of the same name; production abandoned and film remade in B/W by D. W. Griffith as The Birth of a Nation. Lost film.

Multipart actuality. Documentary record of the coronation of 1911 and events surrounding it. Lost film.

Multipart actuality. Documentary record of the coronation of 1911 and events surrounding it. Lost film.

Non-fiction short. Natural history film showing growth of flowers using stop-frame animation. Extant copy: Cineteca di Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

Non-fiction short. Natural history film showing growth of flowers using stop-frame animation. Extant copy: Cineteca di Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

Multipart actuality. Documentary feature on the building of the Panama Canal. Lost film.

Multipart actuality. Documentary feature on the building of the Panama Canal. Lost film.

Actuality. A record of the unveiling of a memorial to Queen Victoria in London. Lost film.

Actuality. A record of the unveiling of a memorial to Queen Victoria in London. Lost film.

Multipart actuality – 2 hrs 30 mins length. Documentary record of festivities held in India to mark the coronation of King George V, and his proclamation as Emperor of India. Only two sections survive – one reel at Cineteca di Bologna, Bologna. Italy. from section “The Pageant Procession”, and two reels at Russian State Documentary Film & Photo Archive (RGAKFD), Krasnogorsk, Russia, from section “The Royal Review of 50,000 Troops”.

Multipart actuality – 2 hrs 30 mins length. Documentary record of festivities held in India to mark the coronation of King George V, and his proclamation as Emperor of India. Only two sections survive – one reel at Cineteca di Bologna, Bologna. Italy. from section “The Pageant Procession”, and two reels at Russian State Documentary Film & Photo Archive (RGAKFD), Krasnogorsk, Russia, from section “The Royal Review of 50,000 Troops”.

Multipart actuality. Compilation of pre-war records of European armed forces released at the start of World War I. Lost film.

Multipart actuality. Compilation of pre-war records of European armed forces released at the start of World War I. Lost film.

Fiction feature film. Melodrama about the separation of two babies, who experience different fortunes in adulthood. The world’s first released colour fiction feature. Lost film.

Fiction feature film. Melodrama about the separation of two babies, who experience different fortunes in adulthood. The world’s first released colour fiction feature. Lost film.

Three-reel drama based on famous kabuki play set among samurai in twelfth-century Japan. The first Kinemacolor drama made in Japan. Lost film.

Three-reel drama based on famous kabuki play set among samurai in twelfth-century Japan. The first Kinemacolor drama made in Japan. Lost film.

Technology

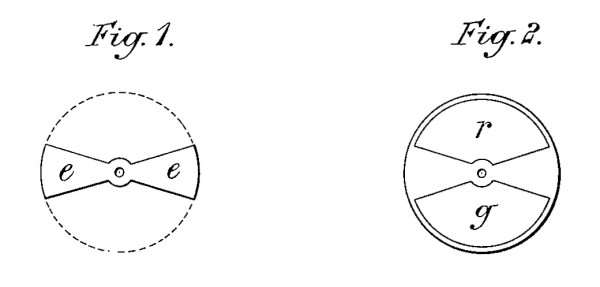

Kinemacolor was a two-colour additive process which achieved its colour effect through a rotating filter, with red and green sections of coloured glass, attached to both camera and projector. Kinemacolor’s inventor G. A. Smith had discovered that an imperfect, but satisfactory, colour record could be obtained using only two of the primary colours. In practice, Smith found it necessary to use a variation on the theoretical red–green formula, settling on a red-orange/blue-green arrangement (McKernan, 2013:pp. 82–3). Further variations on this would be used throughout Kinemacolor’s history, depending on the subject being filmed, though restoration work in the 1990s by the Cineteca Bologna suggests that while the blue-green filter remained constant, the red-range filter required tweaking, adding more or less of a yellow component to achieve a credible colour result (Mazzanti, 2002: p. 125). Originally, standard Urban Bioscope projectors were used, but the double-speed frame rate led to heavy wear of the film. Dedicated Kinemacolor projectors were therefore developed by Henry Joy in 1910 with two eccentric rollers, employing a beater, or “dog”, pull-down mechanism to ensure proper intermittent motion, which was driven by an electric motor (Thomas, 1969: pp. 19–20).

Smith’s other great contribution was his success in sensitizing emulsions in the absence of panchromatic film stock sensitive to the full visible spectrum (such film stock did not become generally available until the 1920s) (Coe, 1981: p. 89). The formula for the sensitizing chemicals during Kinemacolor’s heyday was kept a jealously guarded secret. The negative film used for Kinemacolor was therefore B/W, with successive frames taking a “red” and “green” record, with variation in tonal range, in what otherwise appeared to be B/W images. It was therefore necessary for twice as much film to be used to record any subject as would be taken with conventional film, and for both camera and projector to operate at approximately double speed (Smith’s patent suggested a speed of 30 fps). In projection, the projector was laced up so that the rotating filter wheel was synchronised to the footage, such that the “red” frame would be shown with light coming through the “red” filter, followed by “green” frame and the “green” filter.

Kinemacolor had three significant technical limitations: fringing, frame rate and colour reproduction. Temporal fringing was an inevitable consequence of the alternating “red” and “green” records. The fraction of difference in time between shooting or displaying the two, particularly for objects in motion, led to fringes of red or green which detracted from the colour effect and the films’ realism. The preference shown by Kinemacolor production for travel scenes and slow-moving processions was therefore a practical one, though contemporary commentators noted that colour fringing, in general, was not as pronounced as might have been expected (McKernan, 2013: p.115).

Kinemacolor’s low frame rate in projection led to frequent audience complaints of eye-strain. This was due to the use of two-bladed projection shutters at this period, making the standard 16 fps frame rate close to the threshold at which the viewer became aware of an interval between the frames, known as “flicker”. Kinemacolor was projected at double-speed, but because it had double the number of frames to project, this kept it at the threshold of what audiences would tolerate (Klein, 1936: p. 10).

Colour fidelity was also an issue because only two colour records were employed, whereas human color vision is trichromatic. The absence of reproduceable blues, a facility noted in the 1906 patent, was the reason given for the revocation of that patent in 1914, but the phenomenon of “colour constancy”, whereby the human eye can perceive colours it expects to see, even if, technically, light of such wavelength are not present, made Kinemacolor a more authentic colour experience than a mere patent was able to suggest (McKernan, 2013: p. 116–8). Ultimately, Kinemacolor did not “fail” for any technical reasons, but because its commercial exclusivity was lost once the patent case was lost.

Schematic of the shutter (e) in a conventional camera, and the red and green filters (r and g) used in the Kinemacolor camera.

Smith, George Albert. Kinematograph Apparatus for the Production of Coloured Pictures. US Patent 941,960, filed June 11, 1907, and issued November 30, 1909.

No. 1 Kinemacolor camera, 1909.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

35mm Kinemacolor projector, No. 66, 1910.

Digitally synthesized colour image from the Natural Color Kinematograph Company’s Kinemacolor documentary film production, With Our King and Queen Through India (UK 1912). Note the colour fringing on the elephant’s headdress and the wheel of the carriage.

Cineteca di Bologna / L’Immagine Ritrovata, Bologna, Italy.

References

Bowser, Eileen (1990). The Transformation of Cinema 1907–1915 (History of the American Cinema Vol. 2). Berkeley, CA & London: University of California Press.

Coe, Brian (1981). The History of Movie Photography. London: Ash & Grant.

Komatu, Hiroshi (1995). “From Natural Colour to the Pure Motion Drama: The Meaning of Tenkatsu Company in the 1910s of Japanese Film History”. Film History, 7:1: pp. 69–86

Gervasio, Livio (2017). “Kinemacolor in Italy”. In Mariann Lewinsky & Luke McKernan (eds.), Kinemacolor e Altre Magie / Kinemacolor and Other Magic [DVD with booklet]. Bologna: Cineteca di Bologna: pp. 37–9

Klein, Adrian Bernard (1936). Colour Cinematography. London: Chapman & Hall.

McKernan, Luke (2002). “Propaganda, Patriotism and Profit: Charles Urban and British official war films in America during the First World War”. Film History, 14:3-4: pp. 370–89.

McKernan, Luke (2005). “The Brighton School and the Quest for Natural Colour”. In Simon Popple & Vanessa Toulmin (eds.), Visual Delights – Two: Exhibition and Reception. Eastleigh: John Libbey.

McKernan, Luke (2013). Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897–1925. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Mazzanti, Nicola (2002). “Raising the Colours (Restoring Kinemacolor)”. In Roger Smither (ed.), This Film is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film. Bruxelles: FIAF: pp. 123–5

Thomas, D. B. (1969). The First Colour Motion Pictures. London: HMSO.

Urban, Charles (n.d.). Charles Urban papers, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, UK

Urban, Charles (n.d.). Charles Urban, Motion Picture Pioneer [website]. https://www.charlesurban.com

Patents

Smith, George Albert. Improvements in & Relating to Kinematograph Apparatus for the Production of Coloured Pictures. British Patent B.P. 26671, filed November 24, 1906, and issued July 25, 1907. https://patents.google.com/patent/GB190626671A

Smith, George Albert. Procédé et appareil pour la projection d’images colorées. French patent, F.P. 376,837, filed April 17, 1907, and issued August 22, 1907. https://patents.google.com/patent/FR376837A

Smith, George Albert. Kinematograph Apparatus for the Production of Colored Pictures. US Patent 941,960, filed June 11, 1907, and issued November 30, 1909. https://patents.google.com/patent/US941960A

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Luke McKernan is a media historian. Now retired, he has worked at the British Film Institute (cataloguer), the British Universities Film & Video Council (Head of Information) and the British Library (Lead Curator, News and Moving Image). His publications include Topical Budget: The Great British News Film (BFI, 1992), Walking Shadows: Shakespeare in the National Film and Television Archive (BFI, 1994) [co-editor with Olwen Terris], Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema: A Worldwide Survey (BFI, 1996) [co-editor with Stephen Herbert], Yesterday’s News: The British Cinema Newsreel Reader (BUFVC, 2002), Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-Fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897–1925 (University of Exeter Press, 2013), Breaking the News: 500 Years of News in Britain (British Library, 2022) [co-editor with Jackie Harrison] and Picturegoers: A Critical Anthology of Eyewitness Experiences (University of Exeter Press, 2022). Databases he has developed, or managed, include News on Screen (bufvc.ac.uk/newsonscreen), The International Database of Shakespeare on Film, Radio and Television (learningonscreen.ac.uk/shakespeare) and The London Project (londonfilm.bbk.ac.uk). His websites include The Bioscope (thebioscope.net), Charles Urban, Motion Picture Pioneer (charlesurban.com), Picturegoing (picturegoing.com), Theatregoing (theatregoing.com) and Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema (victorian-cinema.net). He publishes regularly online through his personal site, lukemckernan.com.

With thanks to Andrea Meneghelli, Cineteca di Bologna.

McKernan, Luke (2025). “Kinemacolor”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.