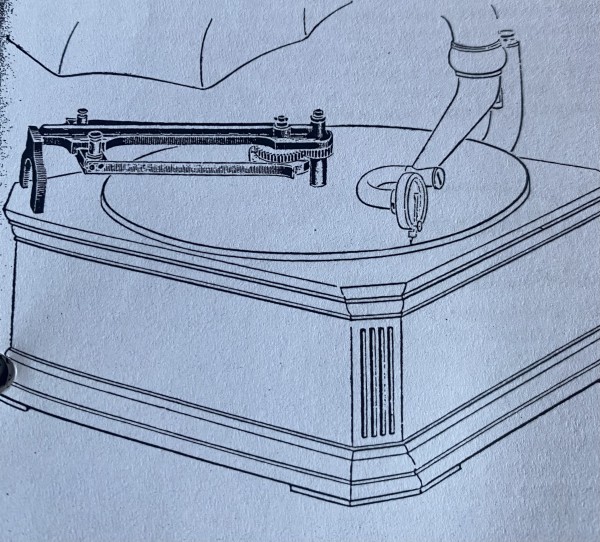

A synchronised sound-on-disc system developed by Cecil Hepworth of the Hepworth Manufacturing Company in Walton-on-Thames, United Kingdom.

Film Explorer

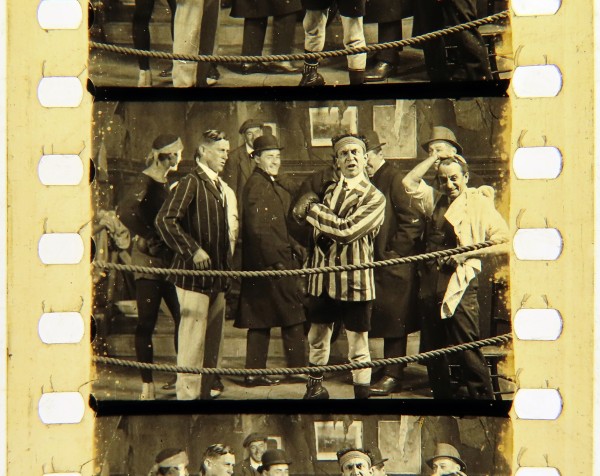

35mm mute full aperture print of The Night I Fought Jack Johnson (c. 1912). This print was synchronised to a 78 rpm sound disc during projection.

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom. Photograph by J. M. Fernandes.

78 rpm disc for Way Back Home (c. 1913). This was a version of a commercially released disc originally published by the Columbia Graphophone Company, specially pressed for use in conjunction with a Hepworth Vivaphone film. Note that a semicircular Vivaphone label has been stuck over the top half of the original recording label.

Courtesy of Simon Brown.

Identification

Approximately 23.6mm x 17.73mm (0.93 in x 0.70 in).

Standard orthochromatic B/W print stock. Manufacturer unknown.

None

1

The films were photographed in B/W; however, some prints contain tinting.

Vivaphone Film

The sound was taken from 78 rpm shellac phonograph records already in circulation and re-issued on 10-inch diameter discs, specially pressed for the system. The Vivaphone discs had grooves on only one side, as well as an additional feeder groove which allowed the projectionist to precisely place the needle, allowing both picture and sound to start in sync.

Approximately 24.9mm x 18.7mm (0.98 in x 0.74 in).

Standard orthochromatic B/W negative. Manufacturer unknown.

History

As reported by the Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly, on November 13, 1908, the Hepworth Manufacturing Company (HMC) held a demonstration at their central London sales office. The film they showed featured a series of dances performed by Miss de Forest Leonard, which had been recorded to a live musical accompaniment on set. The HMC pitch was that they would provide the sheet music with the film print so that any piano player, or orchestra, accompanying the film, could play the score in time with the dances (Anon., 1908).

The title of the film, and whether it was commercially shown, is unknown, but the significance of this experiment lies not in the idea of supplying sheet music, but rather in capturing a live performance responding to a musical recording played on set, then providing both picture and sound for projection purposes. Such was the basis of the Vivaphone, a system that was, by 1908, already in development at the Hepworth Studios in Walton-on-Thames and which represented Hepworth’s contribution to the series of contemporaneous experiments in synchronous sound films that included Will Barker’s Cinephone and the Gaumont Chronophone.

Invented by the HMC’s founder and director, Cecil Milton Hepworth, the Vivaphone was shown to the trade in February 1909 and launched in the spring of the same year. At the launch, around 20 Vivaphone films were available, with the number quickly expanding. According to the Hepworth actor Chrissie White, the company had what she called ‘Viv Days’ on which they would film several Vivaphone shorts. These usually happened when Hepworth was not at the studio and were overseen by two members of Hepworth’s stock company, Harry Buss and Hay Plumb. (White) Hepworth declared the Vivaphone to be, “easy to do and not worth doing … But I was overruled by the business interests … for out of it we made a great deal of money which was available for worthier purposes.” (Hepworth, 1951)

While Hepworth is referring to other film projects or inventions, one worthy purpose to which he did put the Vivaphone was in the political arena. In January 1910 a press show took place at London’s prestigious Theatre De Luxe in the Strand, at which the HMC demonstrated two films featuring politicians Andrew Bonar Law and Frederick Edwin Smith (later Lord Birkenhead), speaking in favour of tariff reform – an important political topic of the day. According to Hepworth, the two men first visited The Gramophone Company’s studios in Hayes, Middlesex (The Gramophone Company was later colloquially known in the UK by the name of its trademark “His Master’s Voice”, or HMV), to record their speeches onto a Vivaphone disc and then went to the Hepworth studios where they were filmed lip-synching to their own speeches. While these were made commercially available for hire, the films, produced in conjunction with the Daily Mail, were pieces of political propaganda aimed at meetings of the Liberal Unionist Party (which was in favour of tariff reform and opposed to free trade) in the run-up to the 1910 General Election (Hepworth, 1951).

While it was not necessarily the most commercially successful early sound system, the Vivaphone proved to be a popular attraction for exhibitors and audiences, between 1909 and its gradual demise during World War I, with many reports in the trade press of exhibitors adopting it for their shows. The relative cheapness of the system made it very attractive and the use of popular recordings could be crowd pleasing. In 1911, the Kine Weekly reported that over 100 venues in the UK had fitted the Vivaphone – and this grew to, potentially as many as, 500 by 1912 (Anon., 1911; Anon., 1935).

The Vivaphone also had some international success. In 1916 Picturegoer reported that a member of the Hepworth publicity team was told by some wounded Anzac soldiers that the Vivaphone was ‘extremely popular in Australia’ (Anon., 1916). Three years earlier, in January 1913, Albert Blinkhorn, an Englishman who had run a number of London cinemas, left for America to set up a US sales office for British films. Blinkhorn secured the rights to Hepworth’s invention for the US and Canada, and, in the spring of 1913, he gave a private exhibition of the system to the trade in New York City (Anon., 1913a). In August, by which time Blinkhorn’s company was called The Vivaphone Film and Sales Co and was the sales agent for all Hepworth films in the US and Canada, he travelled back to the UK to make a deal with Hepworth to start making his own Vivaphone films in America (Anon., 1913c). The London Evening News reported in May 1913 that, ‘Americans are taking to the English Vivaphone like a duck takes to water. They are clamouring for it all over the States.’ (Anon., 1913b)

There is no specific date as to when the Vivaphone died out, but between 1915 and 1916 the number of mentions in the trade press dropped off dramatically. There are many possible reasons for this. The technology was not infallible, and even if it were, the fact that, as noted in the Technology section below, the system relied upon the use of gramophone players in venues, rather than speakers, limited the amplification – this rendered the audibility of the recordings poor in the larger venues. More important, perhaps, was the status of the Vivaphone as a novelty. After five or six years, the novelty had most likely worn off, meaning either its presence simply wasn’t worth reporting any more, or that enthusiasm among audiences had waned and exhibitors stopped showing Vivaphone films. As Richard Abel and Rick Altman have suggested, the rise to prominence of synchronous sound systems in the years before World War I coincided with a representational shift in films away from attractions and novelty, towards longer, more-integrated narratives. (Abel & Altman 1999) Like many of its competitors, the attraction of the Vivaphone relied almost exclusively on the performers miming to popular recordings of the day and was limited by the length of the material that could be captured on a single disc. As cinema moved increasingly towards storytelling and feature films during the latter half of World War I, interest in the Vivaphone slowly ebbed away.

Selected Filmography

Sung by Charles Bignell. Featuring Hay Plumb, Madge Campbell, Jack Hulcup, Chrissie White, Alma Taylor, Jamie Darling (“Whimsical Walker”) and Frank Wilson. Matrix no. 12275e. The Twin Records cat. no. T-2301. Recording date: September 8, 1910. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Sung by Charles Bignell. Featuring Hay Plumb, Madge Campbell, Jack Hulcup, Chrissie White, Alma Taylor, Jamie Darling (“Whimsical Walker”) and Frank Wilson. Matrix no. 12275e. The Twin Records cat. no. T-2301. Recording date: September 8, 1910. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Sung by Jack Charman. Featuring Alma Taylor Violet Hopson and Madge Campbell. Matrix no. 41351(Beka Records). Beka Records cat. no. 482. Albion Records cat. no. 1243. Recording date: unknown. Beka issue date: December, 1911. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Sung by Jack Charman. Featuring Alma Taylor Violet Hopson and Madge Campbell. Matrix no. 41351(Beka Records). Beka Records cat. no. 482. Albion Records cat. no. 1243. Recording date: unknown. Beka issue date: December, 1911. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Sung by Billy Williams. Matrix no. unknown. Face no. 23574. Jumbo Records cat. No. 899. Recording date November, 1912. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Sung by Billy Williams. Matrix no. unknown. Face no. 23574. Jumbo Records cat. No. 899. Recording date November, 1912. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Sung by Harry Fay. Featuring Harry Buss. Matrix no. ae15266e. Zonophone Records cat. No. 882. Recording date: June 27, 1912. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Sung by Harry Fay. Featuring Harry Buss. Matrix no. ae15266e. Zonophone Records cat. No. 882. Recording date: June 27, 1912. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Sung by Jock Lorimer. Matrix no. 11718e. Zonophone Records cat. No. 551. Recording date: May 31, 1910. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Sung by Jock Lorimer. Matrix no. 11718e. Zonophone Records cat. No. 551. Recording date: May 31, 1910. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Sung by Randall Jackson. Matrix no. 26599 (London Recording). Columbia Phonograph Company cat. no. 1129. Recording date: unknown. Issue date: May, 1909. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Sung by Randall Jackson. Matrix no. 26599 (London Recording). Columbia Phonograph Company cat. no. 1129. Recording date: unknown. Issue date: May, 1909. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Sung by, and featuring, George Grossmith and Edmund Payne. Matrix no. z4916. His Masters’s Voice Records cat. no. 04085. Recording date: March 21, 1911. Survives incomplete. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Sung by, and featuring, George Grossmith and Edmund Payne. Matrix no. z4916. His Masters’s Voice Records cat. no. 04085. Recording date: March 21, 1911. Survives incomplete. Restored by the British Film Institute.

Performed by Peerless American Quartet. Matrix no. 38559 (USA). Columbia Phonograph Company (UK) cat. no. 2248. Recording date: c. Jan, 1913. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Performed by Peerless American Quartet. Matrix no. 38559 (USA). Columbia Phonograph Company (UK) cat. no. 2248. Recording date: c. Jan, 1913. Vivaphone sound disc survives.

Technology

The Vivaphone was a means of keeping perfect synchronisation between the projector showing the image and the gramophone playing the sound from the disc.

To produce a Vivaphone film, the action was performed on set by members of the Hepworth stock company, who would mime to a pre-recorded, commercially available gramophone record. The songs therefore were recordings by other artists, not by the Hepworth performers. The actors would learn the words and block out basic choreography – then the record would play and they would mime along as the film was shot. Although the recordings that the performers mimed to on set were commercially available, the Vivaphone discs themselves were specially made for Hepworth. They were pressed on one side only and featured a lead-in slot so that the projectionist could easily find the right spot to place the needle, so that the disc and print commenced in sync. Surviving Vivaphone discs show that the standard round labels usually placed at the centre of a record were used and a special, semicircular Vivaphone label was stuck over the top.

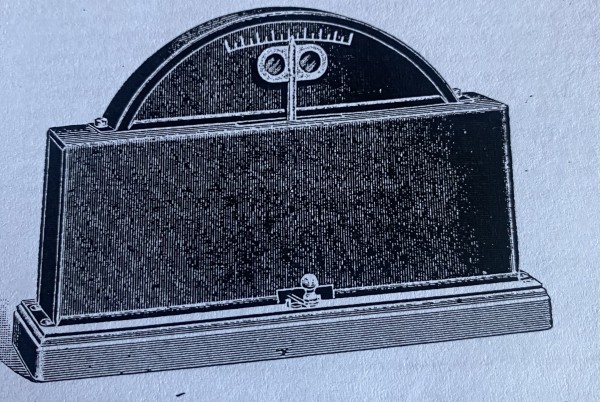

In the cinema venue, the print was projected from the booth and the record was played on a gramophone player, which could be placed anywhere in the auditorium – most likely either behind, or to the side of the screen, or in the projection box. The sound, therefore, came directly from the gramophone horn and was not additionally amplified. The Vivaphone mechanism, itself, comprised a special commutator arm, which fitted over the spindle that held the disc in place on the gramophone. This was connected by wire to a synchroniser in the projection box – with another commutator attached to the projector handle. The synchroniser was basically an indicating needle controlled by two electromagnets: the one attached to the gramophone pulled the needle one way, the other, attached to the projector, pulled it in the opposite direction. When the needle was pointing directly upright, this indicated that the two magnets were in perfect balance – and, thus, picture and sound were in sync. The needle shifting to the left or right indicated that the film print was running either faster or slower than the record, allowing the projectionist to make adjustments to the speed of the projector to compensate. To make these movements more obvious, either side of the needle were small red and green windows, which were illuminated, so that any deviation would cause the projectionist to immediately see either a red, or green, warning light (Anon., 1909a).

The system was therefore simple to install and operate, comprised few parts (and thus at five guineas [a guinea was one pound and one shilling] was priced relatively cheaply), could be fitted to more or less any projector, or gramophone player, and ran off standard batteries. The HMC boasted that the synchronisation achieved was accurate to one-sixteenth of a second and could be used in any sized cinema – although in reality, the relatively small amount of amplification achievable with a standard gramophone meant that it was unsuitable for larger venues. However, they suggested that in combination with an enhanced volume system, such as the Auxetophone, it would work perfectly well in ‘the largest theatre ever built’, although, given the very high cost of the Auxetophone ($500 in the US), this was a very optimistic suggestion (Anon., 1909b).

References

Abel, Richard & Rick Altman (1999). “Introduction”. Film History, 11:4: pp. 395–399.

Anon. (1908). Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (November 19, 1908): p. 707.

Anon. (1909a). Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (February 11, 1909): p.1071.

Anon. (1909b). Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (August 26, 1909): p. 761.

Anon. (1911). Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (September 28, 1911): p. 1179.

Anon. (1913a). Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (May 15, 1913): p. 315.

Anon. (1913b). London Evening News (15 May 15, 1913): p. 7.

Anon. (1913c). Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (September 4, 1913): p. 1947.

Anon. (1916). Picturegoer (February 19, 1916): 470.

Anon. (1935). Picturegoer (May 4, 1935): 10.

Bennett, C. (n.d.) ‘Hepworth Vivaphone’. The Silent Era (accessed September 10, 2023). https://www.silentera.com/info/technology/synchSound/vivaphone.html

Brown, Simon (2016). Cecil Hepworth and the Rise of the British Film Industry 1899–1911. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Hepworth, Cecil M. (1951). Came the Dawn: Memories of a Film Pioneer. London: Phoenix House: pp. 99–105.

White, Chrissie (n.d.). Audio Interview with Denis Gifford, tape GL50, Denis Gifford Audiotape Collection, BFI Reuben Library, London, United Kingdom.

Patents

Hepworth, Cecil Miton. 1909. Improvements in or relating to Apparatus for use in Synchronously Operating Combined Cinematographs and Gramphones or the like, British Patent GB190827766A, patented November 11, 1909.

Hepworth, Cecil Milton. 1911. Synchronic Apparatus for Cinematographs and Sound Producing Apparatus, Canadian Patent CA122250A, patented November 30, 1911.

Hepworth, Cecil Milton. 1912. Apparatus for Use in Synchronously Operating Combined Kinematographs and Sound-Production Apparatis, US Patent US1023846A, patented April 23, 1912.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Simon Brown is Associate Professor of Film and Television at Kingston University, London, UK. He has written extensively on many aspects of film history and technology – including early, silent and British cinema, 3D and colour cinematography. His publications include the monograph Cecil Hepworth and the Rise of the British Film Industry 1899–1911 (University of Exeter Press, 2016) a Technical Appendix on colour film processes in Colour Films in Britain: The Negotiation of Innovation 1900–1955 by Sarah Street (BFI Publishing, 2012) and the online article “Dufaycolor: The Spectacle of Reality and British National Cinema” (2002) – available at http://www.bftv.ac.uk/projects/dufaycolor.htm.

I would like to thank Norman Field and Sue Webber for their help and support in researching this entry.

Brown, Simon (2024). “Vivaphone”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.