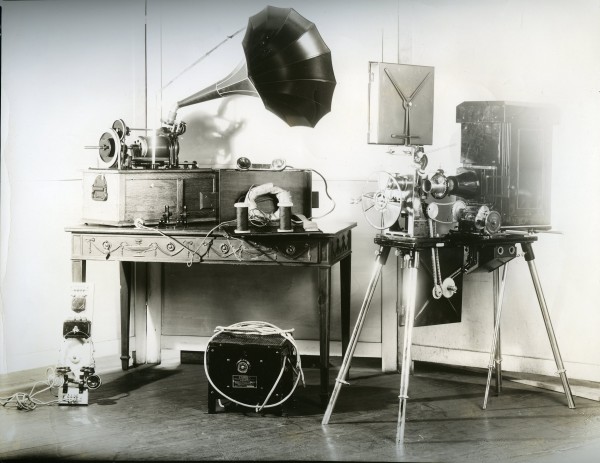

An early system for synchronous-sound films, utilizing a linked 35mm projector and specially designed cylinder phonograph.

Film Explorer

A tinted nitrate release print of Jack’s Joke (Edison Company, US 1913). The print is silent but was synchronized during projection with audio on a cylinder.

National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, United States.

Blue celluloid cylinder for playback.

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

Identification

23.65mm x 17.73mm (0.931 in 0.698 in).

Standard B/W orthochromatic emulsion, sometimes tinted.

None

1

“Edison Kinetophone” appears on the main title card.

A mute 35mm print was synchronized with an Edison Kinetophone Cylinder (7.5 in length, 5 in diameter [190.5mm x 127mm]). Made of a plaster core covered with blue celluloid – identical to the four-minute Edison “Blue Amberol” cylinders for home use.

24.9mm x 18.67mm (0.980 in x 0.735 in).

Standard B/W orthochromatic emulsion.

Unknown

History

Shortly after the development of the Kinetograph camera and Kinetoscope viewing machine, Thomas Edison put his technicians, headed by William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, to work to find a method for adding sound to the new motion picture using the Edison cylinder phonograph then being commercially produced. Early demonstrations were made in the 1890s, but much more development was required prior to the Kinetophone’s public unveiling, on February 17, 1913.

An area was set up in Edison’s New York motion picture studio in the Bronx for the filming and recording of Kinetophones. The film negatives and master sound cylinders were then shipped to Edison’s West Orange, New Jersey, facility for post-production work to prepare the films for exhibition. This included adding titles and a one-second synchronization mark of blank frames to the negative; making prints; re-recording a new master cylinder with additional amplification, and molding new release cylinders. American Kinetophone productions were directed by Allen Ramsay, with orchestral accompaniments (when needed) led by Eugene. A. Jaudas, musical director at Edison’s principal recording studio at 79 5th Avenue, in Manhattan, who conducted an orchestra, selected from Edison’s regular musicians, off-screen during the filming of Kinetophones.

The Edison Company made a decision to exhibit these films separately from the standard Edison Studio silent film productions, making them available to vaudeville houses as an act on the program. To that end, The American Talking Picture Company was formed to sell Kinetophone equipment and distribute the films and cylinders. Three Kinetophone films made up a program. These films would be mounted on a single reel, with 100 ft of black film spliced in between to allow the phonograph operator time to switch sound cylinders.

The debut of the Kinetophone in New York was very successful. At least three films were presented: Edison Kinetophone (The Lecture), The Five Bachelors and The Edison Minstrels. Newspaper reports note that audiences gave the Kinetophone performance a 15-minute ovation and tried to get Mr. Edison to come out on stage, which he refused to do. Within a short amount of time, however, the complaints started. The main complaint was the lack of sound synchronization. Mechanical difficulties aside, the human element of needing two operators to man the film projector and phonograph often resulted in picture and sound being out of sync. The other complaint was with the sound: some patrons found it metallic-sounding and unpleasant. In viewing the films today, a third issue becomes apparent: the primitive shooting style. By 1913, film had already begun to develop its unique cinematic language of editing and shot composition. The Kinetophone, by virtue of its sound component, took all that away, creating six-minute “stage presentations”, in which the camera is static and there are no cuts.

The Edison Company filmed around 200 Kinetophones, both in the United States and in Europe, where, according to the Edison Company log, some 29 Kinetophones were made – mostly of operatic selections. None of the European films are known to survive, but a selection of the sound cylinders exists in the archive of the Swedish Radio Corporation and one cylinder bearing a Cyrillic title, which translates to “Ghosts”, is in a private collection. But, after the initial excitement of talking pictures, the popularity waned quickly. In a letter to Thomas Edison dated July 25, 1913, six months after the premiere, M. R. Hutchinson, the man in charge of the Kinetophone project wrote: “The public is interested in seeing Talking Pictures as a Novelty, once or twice, and then they want Longer Subjects and First Class Acting.” Within a year of release, and after the disastrous fire at the Edison plant on December 9, 1914, the Kinetophone system was quietly set aside. As for Kinetophone in Europe, a letter from C. H. Wilson, Edison’s vice president and general manager to Thomas Graf, manager of Edison’s Berlin office, discusses the closing of the Paris and Berlin Kinetophone offices due to a drop in business and the expansion of World War I. This letter is dated October 10, 1914 – almost two months, to the day, from the Edison Fire.

One interesting side note, found in an article by Jan Olsson in Film History (Olsson, 1999), is that an independent producer in Sweden set up a Kinetophone studio and produced a short run of film, which premiered in Stockholm in February of 1914. However, due to Edison’s decision to discontinue Kinetophone, causing a lack of materials and the ever-worsening situation with World War I, the Swedish concern was bankrupt and gone by 1916.

Selected Filmography

One of the last Kinetophones shot in the Bronx Studio features noted industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie speaking on “The Duty of the Wealthy Man”. The film has not survived, but the sound cylinder is preserved at the Edison Historic Site and can be accessed here: https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/photosmultimedia/upload/EDIS-SRP-0199-06.mp3

One of the last Kinetophones shot in the Bronx Studio features noted industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie speaking on “The Duty of the Wealthy Man”. The film has not survived, but the sound cylinder is preserved at the Edison Historic Site and can be accessed here: https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/photosmultimedia/upload/EDIS-SRP-0199-06.mp3

This film is not found in the log of the Edison Company. In the film, Thomas Watson, Alexander Graham Bell’s assistant, speaks about his part in the development of the telephone. The film has not survived, but the sound cylinder is preserved at the Edison Historic Site and can be accessed here: https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/photosmultimedia/upload/EDIS-SRP-0199-05.mp3

This film is not found in the log of the Edison Company. In the film, Thomas Watson, Alexander Graham Bell’s assistant, speaks about his part in the development of the telephone. The film has not survived, but the sound cylinder is preserved at the Edison Historic Site and can be accessed here: https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/photosmultimedia/upload/EDIS-SRP-0199-05.mp3

One of the few multi-part Kinetophones, based on a story by Rupert Hughes (Howard Hughes’ uncle). It is also unusual in that it was shot outdoors. While there are two extant cylinders for this production, only the picture portion survives for the first part. Although this is a dramatic Civil War story, where a deaf man is captured by Union forces and thought to be a spy, the Edison Quartet is also featured singing “Battle Cry of Freedom”. The sound cylinder to part five also survives and concludes the story: tricked by a loud sound, the man does turn out to be a spy.

One of the few multi-part Kinetophones, based on a story by Rupert Hughes (Howard Hughes’ uncle). It is also unusual in that it was shot outdoors. While there are two extant cylinders for this production, only the picture portion survives for the first part. Although this is a dramatic Civil War story, where a deaf man is captured by Union forces and thought to be a spy, the Edison Quartet is also featured singing “Battle Cry of Freedom”. The sound cylinder to part five also survives and concludes the story: tricked by a loud sound, the man does turn out to be a spy.

Also known as The Lecture, this film features a solitary speaker who extolls the virtues of the Edison Kinetophone system. To that end, he has a pianist play a selection, a singer, dogs, smashing plates, firing guns, etc., to show how well sound and picture synchronize. Only portions of the original soundtrack are extant and the cylinder they were derived from has not been located. This was one of the films presented at the opening night program on February 17, 1913.

Also known as The Lecture, this film features a solitary speaker who extolls the virtues of the Edison Kinetophone system. To that end, he has a pianist play a selection, a singer, dogs, smashing plates, firing guns, etc., to show how well sound and picture synchronize. Only portions of the original soundtrack are extant and the cylinder they were derived from has not been located. This was one of the films presented at the opening night program on February 17, 1913.

Featuring The Edison Quartet, Edward Boulden, Arthur Housman and Eugene Jaudas. Believed to be the earliest sound representation of a typical minstrel show, featuring Arthur Housman as interlocutor and Eugene Jaudas as the orchestra conductor. This is the earliest known synchronized sound film to show a conductor leading a live instrumental ensemble. This was one of the films presented at the opening night program, February 17, 1913.

Featuring The Edison Quartet, Edward Boulden, Arthur Housman and Eugene Jaudas. Believed to be the earliest sound representation of a typical minstrel show, featuring Arthur Housman as interlocutor and Eugene Jaudas as the orchestra conductor. This is the earliest known synchronized sound film to show a conductor leading a live instrumental ensemble. This was one of the films presented at the opening night program, February 17, 1913.

Featuring Edward Boulden and The Edison Quartet. A mixture of music and comedy as Boulden comes to join a secret society and is run through a gauntlet of hazing to prove his worthiness. According to the Edison Company log, this was the third Kinetophone completed and was part of the opening program, February 17, 1913.

Featuring Edward Boulden and The Edison Quartet. A mixture of music and comedy as Boulden comes to join a secret society and is run through a gauntlet of hazing to prove his worthiness. According to the Edison Company log, this was the third Kinetophone completed and was part of the opening program, February 17, 1913.

Edward Boulden plays Jack, who brings his friend, played by Arthur Housman, home and decides to play a prank on both him and his girlfriend, played by Nellie Grant Mitchell. Jack tells both Arthur and Nellie separately that the other one is nearly deaf and then steps away as they proceed to shout at each other. This Kinetophone is one of the best surviving examples of the system, since the original nitrate camera negative survives. It is interesting that two of the surviving Kinetophone films use deafness as a plot element: in Jack’s Joke comically and in The Deaf Mute dramatically.

Edward Boulden plays Jack, who brings his friend, played by Arthur Housman, home and decides to play a prank on both him and his girlfriend, played by Nellie Grant Mitchell. Jack tells both Arthur and Nellie separately that the other one is nearly deaf and then steps away as they proceed to shout at each other. This Kinetophone is one of the best surviving examples of the system, since the original nitrate camera negative survives. It is interesting that two of the surviving Kinetophone films use deafness as a plot element: in Jack’s Joke comically and in The Deaf Mute dramatically.

On a blacksmith shop set, The Edison Quartet sings several songs accompanied by Eugene Jaudas’s off-screen orchestra. A little girl, played by “Little Leonie Flugrath” (better known later as Shirley Mason), brings them lunch as they sing “Sally in Our Alley” to her.

On a blacksmith shop set, The Edison Quartet sings several songs accompanied by Eugene Jaudas’s off-screen orchestra. A little girl, played by “Little Leonie Flugrath” (better known later as Shirley Mason), brings them lunch as they sing “Sally in Our Alley” to her.

One of the best-known Kinetophones, having been made available by Blackhawk Films in both 16mm and 8mm sound in the 1970s. The Edison Quartet along with Leonie Flugrath, Robert Lett and possibly Viola Dana sing and perform as Nursery Rhyme characters. Robert Lett does a wonderful patter song and eccentric dance as Old King Cole This film also features orchestral accompaniment.

One of the best-known Kinetophones, having been made available by Blackhawk Films in both 16mm and 8mm sound in the 1970s. The Edison Quartet along with Leonie Flugrath, Robert Lett and possibly Viola Dana sing and perform as Nursery Rhyme characters. Robert Lett does a wonderful patter song and eccentric dance as Old King Cole This film also features orchestral accompaniment.

Featuring William Bechtel, Albert H. Busby and Cora Williams. A Napoleonic-era drama about an old, French army guard, his daughter and a young officer. The Edison Company records do not give a release date for this, which might be because the original sound is so muffled as to be almost unintelligible. It is also one of the few Kinetophones where the original nitrate negative survives, in addition to being the only one to feature an optical effect – the appearance of Napoleon’s spirit at the end.

Featuring William Bechtel, Albert H. Busby and Cora Williams. A Napoleonic-era drama about an old, French army guard, his daughter and a young officer. The Edison Company records do not give a release date for this, which might be because the original sound is so muffled as to be almost unintelligible. It is also one of the few Kinetophones where the original nitrate negative survives, in addition to being the only one to feature an optical effect – the appearance of Napoleon’s spirit at the end.

A “work for hire” (a designated term in US copyright law, where the commissioning party owns all rights to the resulting work), made at the request of the leaders of the Suffragette Movement. The film features short speeches by several of the suffragettes. A nitrate print survives at The Library of Congress, but the sound cylinder is considered lost.

A “work for hire” (a designated term in US copyright law, where the commissioning party owns all rights to the resulting work), made at the request of the leaders of the Suffragette Movement. The film features short speeches by several of the suffragettes. A nitrate print survives at The Library of Congress, but the sound cylinder is considered lost.

Technology

Filming

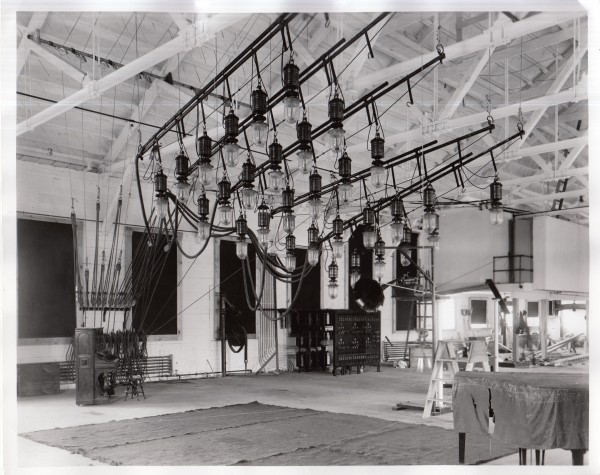

For the filming of a Kinetophone, an electrically operated camera was fixed on a small table, connected to a synchronizing device. The recording phonograph sat above the heads of the performers; a huge horn pointed down to catch the sound. A long pole attached to the other edge of the horn acted as a sort of “microphone boom pole” to readjust the recording horn proximate to the actors as they moved around the set. No camera movement is found in any surviving Kinetophones.

To obtain a running time of up to six minutes, a special phonograph and cylinder had to be developed. Traditional Edison Phonograph cylinders had a typical duration of two to four minutes, with a diameter of 2.25 in (57.2mm), and a length of 4 in (102mm). The new larger Kinetophone cylinders were 5.5 in (139.7mm) in diameter with a length of 7.5 in (190.5mm). The Kinetophone cylinder utilized the same recording arrangement of 100 grooves per inch as the original two-minute commercial cylinders, which allowed for a wider groove, enabling louder playback. The recording cylinder was made of brown wax, while the final playback cylinders had a plaster core covered with blue celluloid – the same as the four-minute Edison “Blue Amberol” cylinders for home use.

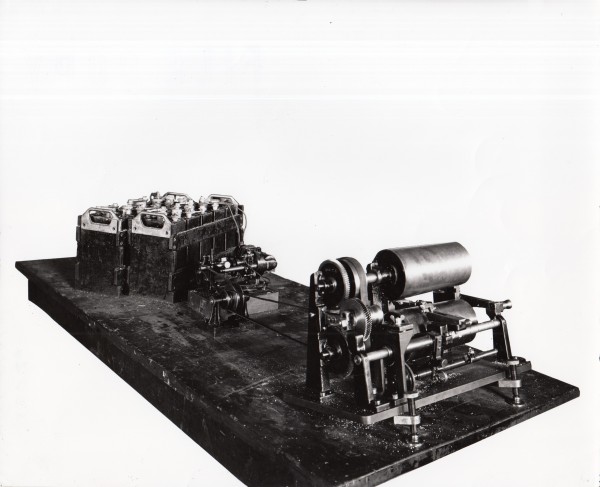

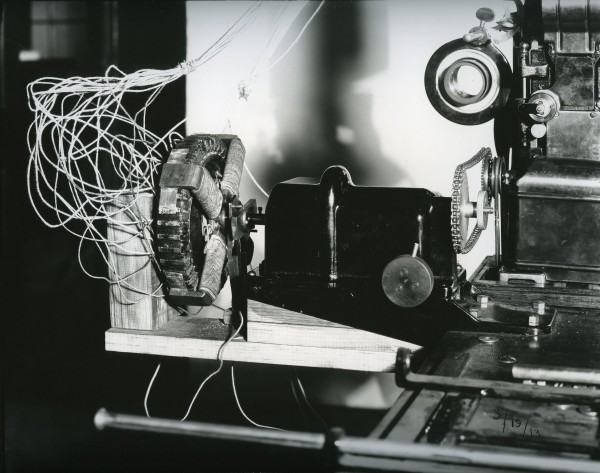

To further amplify the sound, the wax master recording was copied using a pantograph duplicating device which further deepened and widened the groove in the re-recorded master cylinder which, when combined with Charles Higham’s mechanical friction-action amplifier (which had been used on Columbia domestic cylinder phonographs some years earlier), increased final volume output for the completely acoustic system.

Projection

To help with synchronization, an audible marker of two coconut shells smacked together was used – this can be heard at the start of every cylinder. This sound was used as the point where the projectionist would set the stylus on the phonograph, throwing the clutch to start playback as the first image appeared. To further assist with this manual synchronization, one second of black film was placed between the title and first image, giving the operator that one second to prepare.

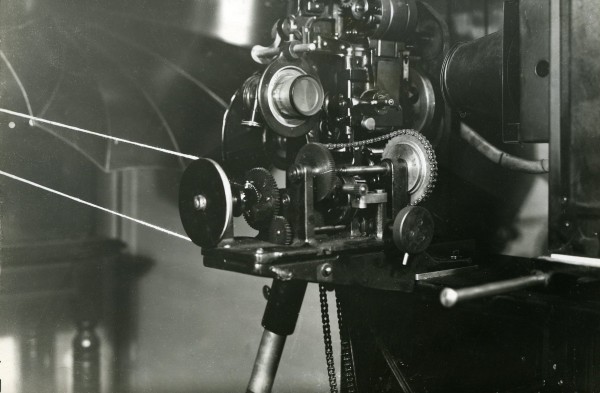

One of the main components of the Kinetophone system was the Synchronizer, which was attached to the rear side of a standard Edison Projecting Kinetoscope. It was further integrated with the projector, by a series of chain drives and then to the phonograph by a long linen belt that was run across the ceiling of the theatre down to the screen area. If the projectionist noticed the sound going out of sync, he could turn a large knob on the synchronizer one direction to advance the film four frames and the other to retard four frames. This required reaching the left arm through the projector – risking a burn from the hot lamp house – while still maintaining proper projection speed with the right arm. Technical photographs from the Thomas Edison National Historic Site show that it was realized very early on that this synchronizer was one of the major weak spots in the system and they quickly tried to find ways to automate the process.

To run a Kinetophone required two technicians: a projectionist and a phonograph operator. The two communicated via a crude electrical headphone setup. The projectionist would start the film, hand-cranking the projector and calling the phonograph operator to tell him to get ready. The phonograph operator would watch the screen, hand on the clutch, waiting for the opening title and one second of black. At the first frame of picture, he would press a button, engaging the running phonograph into gear. Then it was up to the projectionist, through watching and listening and utilizing the control knob on the Synchronizer, to keep the film and sound playing properly together in time.

Kinetophone Studio set up at the Edison Studio in the Bronx, New York City, NY, United States.

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

Left: Kinetophone wax cylinder master.

Right: Kinetophone “Blue Amberol” celluloid cylinder for playback.

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

Pantograph for re-recording of Kinetophone cylinders, utilizing Higham Amplifier.

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

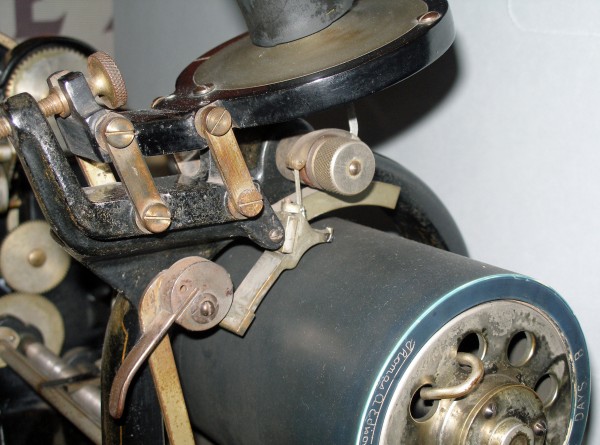

In playback, the phonograph was fitted with a “Higham Amplifier” – a device which further amplified the sound by means of friction against a spinning wheel of rosin.

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

Kinetophone Synchronizer installed on Edison Projector.

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

Edison Lab photos showing attempt to improve the Kinetophone Synchronizer.

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

References

Shifrin, Art (1983). “The Trouble with Kinetophone”. American Cinematographer, 64:9 (September): pp. 50–68.

Blacker, George A. (1981). “Some Comments on the Edison Kinetophone Cylinders of 1912”. Antique Phonograph Monthly, 6:10: pp. 3–7.

Rogoff, Rosalind (1976). “Edison’s Dream: A Brief History of the Kinetophone”. Cinema Journal, 15:2 (Spring / American Film History): pp. 58–68.

Olsson, Jan (1999). “In and out of Sync: Swedish Sound Films 1903–1914”. Film History, 11:4 (Émigré Filmmakers and Filmmaking): pp. 449–455.

Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, NJ, United States. Kinetophone production papers, 1913.

Wilson, C.H. (1914). Letter to Thomas Graf, 10 October 1914. Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange. NJ, United States.

Compare

Related entries

Author

George Willeman has been with the Library of Congress since 1984 and is the Nitrate Film Vault Leader at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in Culpeper, Virginia. In 2016, he undertook the reconstruction of the eight surviving Kinetophone films with sound, utilizing recordings provided by the Thomas Edison National Historic Park in West Orange, New Jersey.

Leonard DeGraff, Valerie Shoffner and Jerry Fabris, Thomas Edison National Historic Site.

Willeman, George R. (2024). “Edison Kinetophone”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.