The earliest-known motion-picture colour photographic process. Still in development at the time of its inventor’s early death, this three-colour additive process achieved limited success as the projection method, though theoretically sound, proved mechanically unstable.

Film Explorer

Frame sequence from the Lee and Turner camera negative of Goldfish in a Bowl (1902), showing the three sequential colour separations.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

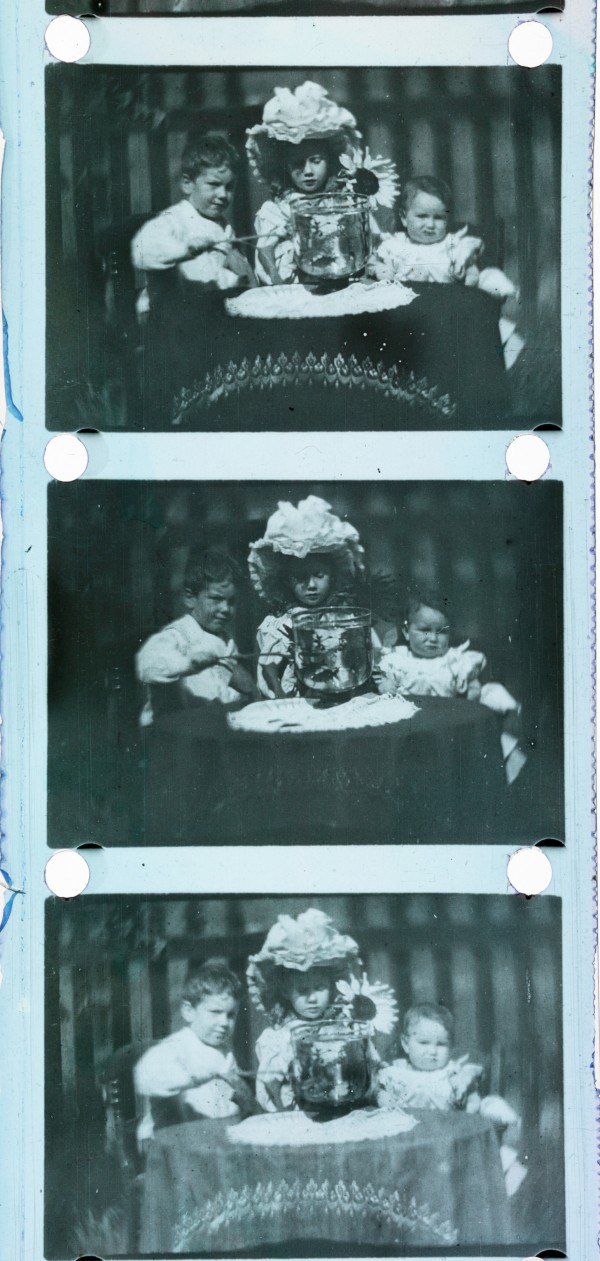

Frame sequence from the Lee and Turner projection print of Edward Turner’s Children (1902), showing the three sequential colour separations.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Identification

(1.5 in.)

22.1 mm x 30.78 mm (0.87 in x 1.2 in).

Single, circular perforation near both edges, between frames, 25.4mm (1 in) pitch.

The film gate was of a height to accommodate three sequential colour records which were projected in register, each through a different lens, as the film advanced one frame at a time. Thus, each frame was projected three times.

B/W

None

Approx.

1

Blue-violet, green and red filters were used in filming to record colour separations on B/W film. Similar colour filters were used in projection to recreate a full-colour image.

(1.5 in.)

22.1 mm x 30.78 mm (0.87 in x 1.2 in).

Single, circular perforation near both edges, between frames, 25.4mm (1 in) pitch.

Each of the three colour records was filmed one frame at a time.

B/W, panchromatic.

None

History

In 1898, Edward Raymond Turner (1873–1903), a professional photographer, started work at The Photochromoscope Syndicate, London – a company established by the American inventor Frederick Ives (1856–1937) to market his stereo, additive three-colour slide viewer, the Krōmskōp, and its associated Krōmōgram slides. The camera Ives invented to make these, employed an arrangement of mirrors, prisms and filters behind the lens to record all three colour separations simultaneously on a single plate. A beam-splitting attachment placed in front of the lens enabled it to take stereo pictures.

Each Krōmōgram consisted of three monochrome glass positives, printed from the negative, which were then cut into separate slides. These were held together by tape hinges, so they could be placed on the three stepped apertures of the Krōmskōp viewer – each of which held the appropriate colour filter to reproduce the full-colour image.

This process inspired Turner to explore applying similar techniques to moving pictures, though Ives later claimed he suggested the idea to him (Ives, 1926). Turner persuaded Frederick Marshall Lee (1871–1914) – a fellow employee, according to Ives – to fund the project and they signed a contract on October 11, 1898 (Ives, 1926). On March 22, 1899, they applied for a patent for a method ‘to produce and exhibit cinematographic pictures in such manner that they are seen in the colours of the originals’. Turner submitted the complete specification on December 22 and was granted the patent on March 3, 1900.

But, as Turner was soon to discover, this was when the real work began. There were challenges associated with colour-sensitizing film stock to the full visible spectrum, as well as mechanical and optical difficulties to overcome. Progress proved slow, and in 1901 the partners sought to interest Charles Urban (1867–1942), an American prominent in the burgeoning British film industry, in the project. Urban, the managing director of the Warwick Trading Company, the foremost producer and distributor of films and equipment in Britain, persuaded his fellow directors to fund Turner for six months. He commissioned Alfred Darling (1862–1931), the leading cinematograph engineer of the day, to construct Turner’s camera and a 38mm film perforator. These were ready by October, enabling Turner to start making test films of London scenes and colourful subjects, such as a Scarlet Macaw and his own children, in their Edwardian finery, at his home in Hounslow.

Nevertheless, by the end of the year, progress was deemed insufficient by Warwick’s directors and they withdrew. Undaunted, Urban undertook to fund Turner himself, despite his colleagues considering him ‘a damned fool’. He bought out Frederick Lee’s interest in September 1902 (Urban, 2003).

Darling completed work on the projector, modified from the patented design, in February 1902.

Then, on March 9, 1903, Turner died – his death certificate citing heart disease, rheumatic fever and pneumonia as the causes. His widow, Edith, was left with three children to support and Urban was left with a project nowhere near ready for commercial exploitation. Urban asked a long-term associate of Warwick’s, George Albert Smith (1864–1959), one of the ‘Brighton School’ of pioneer film makers, who also ran a flourishing processing laboratory, to take over development.

One of the extant films was probably shot by Smith. However, by March 1904 Smith had concluded that the projector could never be made to work as intended. So, the process was abandoned and Smith immediately embarked on developing a sequential-frame two-colour additive process, Kinemacolor.

Urban kept possession of Turner’s films and they passed to the Science Museum, London, as part of the Urban Collection, in 1937. When the Collection was relocated to the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, in 2010, this writer conceived the idea of restoring and realizing the films – applying Turner’s methods using modern imaging technology.

Film archivists, David Cleveland and Brian Pritchard, undertook the task with the collaboration of the BFI National Archive (Cleveland & Pritchard, 2012). Because of the films’ unique 38mm format and mix of negative and positive originals, they were copied frame-by-frame to a 35mm film intermediate, which was then scanned to digital files. These were used to generate the colour composite, at the London facilities house Prime Focus, using the visual effects program Smoke set to emulate the same methods as Turner’s projector. Though the results display the colour fringing associated with sequential-frame processes, the images are steady and the colours remarkably life-like, as promised in the 1899 patent.

The films were shown for the first time, 110 years after they were taken, at a press launch at the Science Museum, London on September 13, 2012, and formed the subject of a BBC TV programme The Race for Colour, transmitted on September 17, 2012.

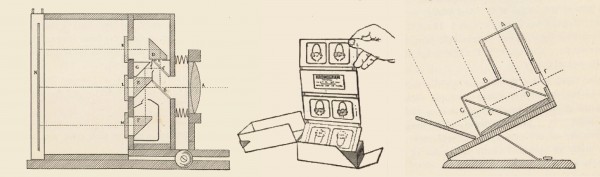

Sectional drawings of the Krōmskōp camera (left) and viewer (right), with an illustration of a Krōmōgram slide (centre). Looking through the viewer eyepiece, F, you saw the green record, C, on which the red and blue records, A and B, reflected by the transparent mirrors, D and E, were superimposed.

Ives, Frederick E. 1898. Krōmskōp Color Photography, London: The Photochromoscope Syndicate Limited.

Test films by Edward Raymond Turner. Left: Knightsbridge, London, looking east towards Hyde Park Corner, 1901/2. Right: Turner’s children at a table with a goldfish and sunflowers, 1902. They are, from left to right, Alfred Raymond (1898–1994), Agnes May (1896–1920) and Wilfred Sidney (1901–1990).

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Test films by Edward Raymond Turner. Left: Agnes May Turner on a swing in the Turner family garden, Hounslow, Middlesex, 1902. Right: Goldfish in a bowl, 1902.

Selected Filmography

Duration: 21 seconds.

Duration: 21 seconds.

Duration: 11 seconds.

Duration: 11 seconds.

Duration: 1 minute 12 seconds.

Duration: 1 minute 12 seconds.

Duration: 9 seconds.

Duration: 9 seconds.

Duration: 4 seconds.

Duration: 4 seconds.

Duration: 24 seconds.

Duration: 24 seconds.

Duration: 37 seconds.

Duration: 37 seconds.

Duration: 16 seconds.

Duration: 16 seconds.

Technology

The first colour cinematography patent was German, filed by Herman Isensee in 1897. It described a three-colour process, but only in the briefest of terms. Of two British patents listed in Adrian Cornwell Clyne’s Colour Cinematography as preceding Lee and Turner’s, one, by William Friese Greene, referred to a photographic process; the other, by Lascelles Davidson, was incorrectly dated 1898, rather than 1899 (Cornwell Clyne, 1951: pp. 4–5).

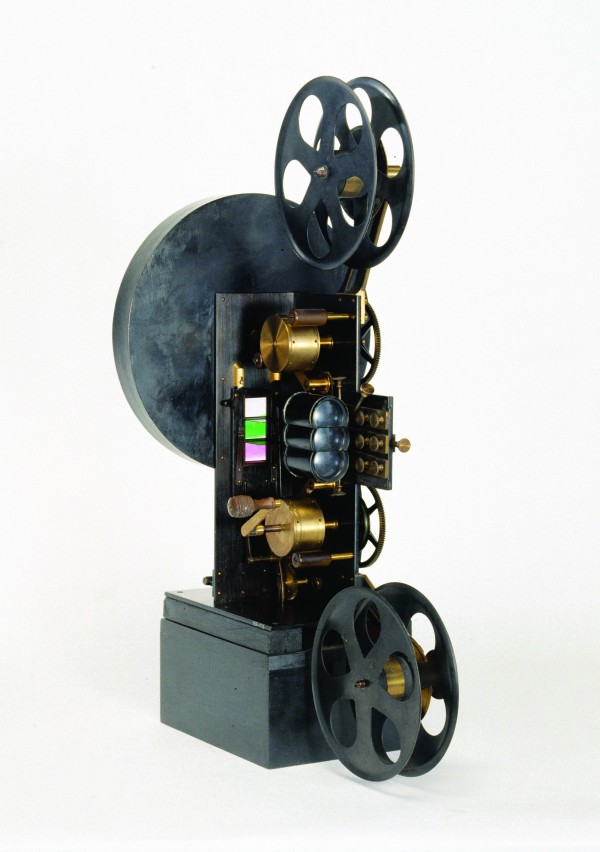

Lee and Turner’s, therefore, is the first such British patent, describing the camera and projector in detail. The camera has not survived, but the projector is in the collection of the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

At that period, film stock was sensitive mostly to the blue end of the spectrum. Anyone devising a colour process had first to treat the film with aniline dyes to extend its colour sensitivity to the green and red regions of the visible spectrum (Jones, 1911: pp. 129–131). Turner probably treated small batches of photographic plates with such dyes while working for Ives, but cine film required a laboratory capable of running long lengths of film through sensitizer baths, then drying them on a high-speed drum before being re-spooled – a three-hour process undertaken in complete darkness (Talbot, 1912; pp. 292–294).

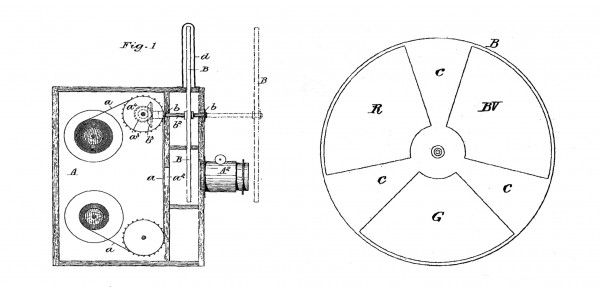

Turner’s camera photographed the colour separations in sequence on 38mm B/W negative film. It had a rotating six-sector shutter wheel, with blue-violet, green and red filters in the open sectors and adjustable shutter blades between. The shutter blades made it possible to vary the exposure proportionate to the light transmission characteristics of each filter – ensuring all three separations were recorded at a similar density. A monochrome print was made for projection.

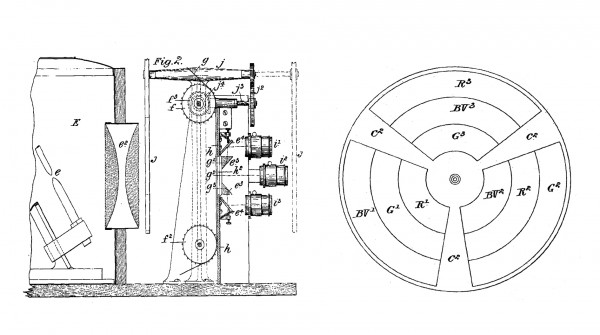

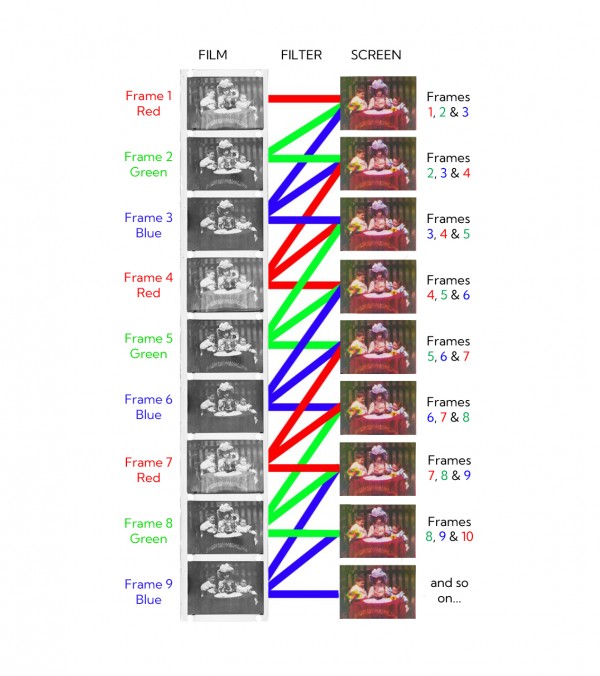

Because it was a sequential-frame process, some historians assumed that it employed a fast frame rate. However, the 2012 restoration established that Turner’s films were shot and projected at around 16 fps. With a design inspired by tri-unial magic lanterns, Turner devised a projector where three sequential colour separations were simultaneously projected in register using a three-frame gate, three lenses and a rotating filter wheel. As the film advanced through the gate, the separations moved down and the next separation of the same colour as the frame which had left the bottom gate, entered at the top.

In front of the gate are three lenses cemented together, a departure from the original design. Behind the gate, in front of the light source, is the filter wheel. This has three segments, each separated by a shutter. Each segment has red, green and blue filter bands, though in different positions, designed so that as each frame moves from the top to the bottom gate it is illuminated by its appropriate colour. The filter rotates in synchrony with the top film sprocket drive, bringing the correct filter segment into place.

Whether its mechanism was insufficiently precise, or the cemented lens arrangement limited control of on-screen registration, the projector did not work as intended. “As soon as the handle of the projecting machine was worked”, observed George Albert Smith, “the three pictures refused to remain in register … and when the minute defects of registration in the first three pictures are followed by minute defects of another sort in the next three … the effect on the observer is almost unbearable.” (Smith, 1908)

Sectional drawing of the Lee & Turner camera (left); and the combined shutter and filter wheel (right), as shown in Lee and Turner’s patent. The shutter (B) is shown in two alternative positions on the camera. The filter colours were red (R), blue-violet (BV), and green (G).

Lee, F. M. & E. R. Turner. Means for Taking and Showing Cinematograph Pictures. British Patent 6202, filed March 22, 1899, and issued March 3, 1900.

Sectional drawing of the Lee & Turner projector (left) and the stepped filter/shutter wheel (right) from Lee and Turner’s patent. The similarity to Ives’ Krōmskōp camera can be seen in the prism and mirror arrangement in front of the film gate (g1, g2 & g3), omitted from Darling’s realisation of the design.

Lee, F. M. & E. R. Turner. Means for Taking and Showing Cinematograph Pictures. British Patent 6202, filed March 22, 1899 and issued March 3, 1900.

Schematic showing how the progressive simultaneous colour sequencing worked. Every frame – with the exception of those at the very start – is shown three times. In any three-frame set, there is a 1/8-second gap between the first and last frames, leading to colour fringing of any significant movement in a shot.

Courtesy of Michael Harvey.

The Lee and Turner projector, seen from the front, showing the stacked lenses, the three-frame gate and filter wheel.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Left: Close-up showing how the lenses align with the gate and filters. The blue-violet filter (at the top of the gate) has faded over time.

Right: The filter wheel and shutter blades, shown from the lamphouse side. As the film moves through the projector, the filter colours change accordingly. Note the filter banding differs from that shown in the patent with red and green reversed.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

References

BBC Television (2012) The Race for Colour. Producer/director: Vince Casey. 29 minutes. Broadcast, BBC1 South East & Yorkshire, September 17, 2012.

Cleveland, David & Brian Pritchard, (2012). “Restoring Lee & Turner's 1902 Colour Films”. Archive Zones, 84 (Winter): pp. 8–10.

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography (3rd edn). London: Chapman & Hall. https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.11295

Ives, Frederick E. (1898). Krōmskōp Color Photography. London: The Photochromoscope Syndicate Ltd. https://archive.org/details/kromskopcolorpho00ives_1/mode/1up

Ives, Frederick E. (1926). “Subtractive Color Motion Pictures on Single Coated Film”. Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 25 (September): pp. 74–78. https://archive.org/details/transactionsofso25soci/page/n79/mode/2up

Jones, Bernard E. (1911). Cassell’s Cyclopaedia of Photography. London: Cassell & Company. Republished in 1983 as The Encyclopaedia of Early Photography. London: The Bishopsgate Press.

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.167822/page/n153/mode/2up

Smith, G. Albert. (1908). “Animated Photographs in Natural Colours”. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 57:2925 (December 11): pp. 70–76.

Talbot, Frederick A. (1912). Moving Pictures: How They Are Made and Worked. London: William Heinemann. https://archive.org/details/cu31924030699445/page/n395/mode/2up

Urban, Charles. (2003). “Terse History of Natural Colour Kinematography” (with an introduction by Luke McKernan), Living Pictures: The Journal of the Popular and the Projected Image Before 1914, 2:2: pp. 60–68. Transcribed from the 1921 manuscript, File no URB 9/1/1, Charles Urban Collection, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Patents

Lee, F. M. & E. R. Turner. Means for Taking and Showing Cinematograph Pictures. British Patent 6202, filed March 22, 1899 and issued March 3, 1900.

Lee, Frederick Marshall & Edward Raymond Turner. Kinetographic Camera. US Patent 645,477, filed October 14, 1899 and issued March 13, 1900.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Following a career as a professional photographer and film, video and multivision programme maker, Michael Harvey was, until 2013, Curator of Cinematography at the National Media Museum, Bradford, UK (now the National Science and Media Museum). He was responsible for managing its world-class collection of professional and amateur cinema technology, broadening it to reflect the realities of film production with the addition of artwork, photographs, posters, documentary material and discrete collections such as that of the Hammer Films special effects make-up artists.

He curated major exhibitions including Magic Behind the Screen: 100 Years of British Cinema (1996); Bond, James Bond (2002), which toured to major venues in the USA and Canada; Myths and Visions: The Art of Ray Harryhausen (2006); Live by the Lens, Die by the Lens: Film Stars and Photographers (2008); and Drawings that Move: the Art of Joanna Quinn (2009). He also initiated a long-term series of on-stage interviews with those working in the wide range of disciplines involved in film and television production, under the banner Script to Screen.

In 2012, his work on researching and realising the first colour moving images from the original footage by Edward Raymond Turner in the Museum’s collection attracted worldwide media attention.

My thanks to former colleague Toni Booth at the National Science and Media Museum for accessing original objects and artefacts to check measurements.

Harvey, Michael (2024). “Lee and Turner process”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.