An additive three-color lenticular screen process developed by Rodolphe Berthon and the company Société française de cinématographie et de photographie en couleurs Keller-Dorian.

Film Explorer

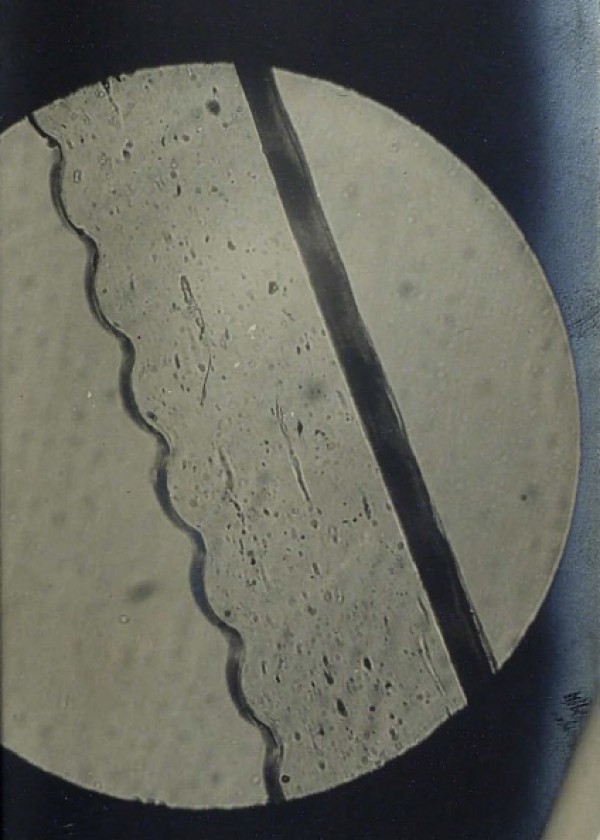

Unidentified film (1920s). 35mm B/W reversal original on nitrate film base with horizontal embossing. The original colors in the film were revealed in projection with a three-banded RGB filter.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

Identification

History

The Keller-Dorian process was an additive color process invented and patented by the French physicist Rodolphe Berthon in 1908. His invention was directly inspired by Gabriel Lippmann’s work on “integral photography” – a relief film process which involved embossing film with lenticular elements. Berthon adapted Lippmann’s idea for color cinematography.

This process allowed color information to be captured on a B/W emulsion, the colors were then revealed in projection using a trichrome filter. The lenticular process can be considered as a screen process, but the array is formed entirely by optical means. A red, green and blue three-banded filter was placed in the lens system, and the screen image was formed by microscopic optical elements engraved on the film base. When the principle was unveiled, most specialists considered it the most elegant solution to the problem of color motion pictures so far discovered.

In 1913, Berthon, who had acquired a certain notoriety, was hired by Charles Pathé as a research engineer. This was an opportunity for him to undertake the development of a film embossing machine and to carry out research on the panchromatization of the film (sensitizing B/W emulsion to the full visible spectrum). The reports he wrote were subsequently used by Pathé to file a patent in the name of his company, without including Berthon’s name on the patent. Feeling cheated, Berthon left the Pathé company in March 1914.

The First World War interrupted further research into the technology in France. After the war, Berthon was in search of practical, scalable solutions and joined forces with the industrialist, Albert Keller-Dorian who ran a custom fabric engraving plant in Mulhouse and in Lyon. Keller-Dorian’s curiosity for photographic technology led him to move in scientific circles, where he came into contact with Berthon and his invention and began work on devising the technology for an embossing machine that would constitute the foundation of the lenticular process. In 1924, some test footage was shown, but the problems associated with making prints of reliable quality were far from being resolved. Soon after the founding of ‘La Société du Film en couleurs Keller-Dorian’ in 1924, Albert Keller-Dorian died and a serious disagreement occurred between the shareholders – who were demanding immediate results – and the research team, who considered that the process was not yet ready to be commercialized. By this time Berthon had been sidelined, and it was Professor Henri Chrétien who was leading the research, but he soon resigned in protest. His departure interrupted any further serious progress.

Eastman Kodak, developing an interest in the process, sent over its engineering consultant, Raymond Edwin Crowther from the US. Kodak acquired the patent for 16mm and launched Kodacolor in 1928, which was well suited to the amateur market. The reversal film enabled direct projections without having to make prints. And later, in the early 1930s, after Berthon's original 1909 patent had fallen into the public domain, the German company Agfa took out a similar patent under the trademark of Agfacolor, also with the intent of bringing color to the 16mm amateur market.

In the UK, Louis Blattner, who was involved in research on magnetic sound recording, became interested in the Keller-Dorian process and bought the rights for Great Britain in 1929. The process, renamed Moviecolor, was short-lived, because Eastman Kodak refused to supply him with embossed film, and Blattner sold back the rights a year later.

In 1930, the French company (Société française de cinématographie et de photographie en couleurs Keller-Dorian) was declared insolvent and the patents were purchased by William Celestin at the head of an Anglo-American group under the name of ‘Keller-Dorian Colorfilm of America’. Kodak, Technicolor and Paramount acquired several patents and conducted research to deal with the problem of producing prints at an industrial scale. After the purchase of these patents, the activity of the French color film company Keller-Dorian was put on hold.

At the same time, Berthon founded a new rival company, La Cinéchromatique, and continued his research into the problem of making prints. But the funds at his disposal were very limited. Berthon entered into a partnership with the Kyslin Corporation, to exploit his patents in the US. Additions to the Berthon’s patents were filed by Kyslin and research engineer Carl Gregory but the project was not commercially developed.

In 1931, the Siemens-Halske German trust purchased the La Cinéchromatique patents. After four years of research, company engineers succeeded in making good-quality embossed prints. In 1936, the first German fiction color film, Das Schönheitsfleckchen (The Beauty Spot) was shown in Berlin during the Olympic games and the film made a notable international impact.

In 1938, Agfa developed Pantachrom, a bipack lenticular process, but Agfa’s own parallel advances in a subtractive monopack film led to the rapid demise of lenticular film development in Germany. Both Agfa and Siemens-Halske had withdrawn from further lenticular development by the end of 1938.

In the early 1930s, the French company Thomson-Houston had undertaken research and shot test footage without much to show for their efforts, then all activity ceased due to the advent of the Second World War. After the Liberation, Thomson-Houston made a new attempt to relaunch its Thomsoncolor process, announcing in 1947 that Jacques Tati’s Jour de Fête was to be its first color production. But the Thomsoncolor printing process failed and the film was eventually distributed only in a B/W version.

In the 1950s, the lenticular process made one last comeback with Eastman Embossed Color Kinescope Recording film, type 5209, used to record color television programs. This technology made it possible to record live shows at a stage when magnetic videotape recording was still only an experimental technology.

The Keller-Dorian process, although based on an elegant and promising idea, never got beyond the experimental stage. It was another 80 years before Lippmann’s work on micro-lenses was to arouse interest again – leading to technology used today in domains as varied as astronomy, holography and fiber optics. While the Bayer matrices used in digital camera sensors (charge-coupled devices, or CCDs) are based on the same underlying principles of lenticular pattern processes.

Matteo Falcone (1928). Left: Actor Chakatouny in B/W on the original reversal film. Right: Frame from a 35mm Eastmancolor negative made from a lenticular Keller-Dorian original after the color was reconstructed through an RGB filter on an optical printer.

Courtesy of Bernard Tichit.

[Untitled film by Sonia Delaunay] (1926). Frame from a 35mm Eastmancolor negative made from a lenticular Keller-Dorian original with vertical embossing. Color decoding was carried out on an optical printer equipped with a trichromatic selection filter.

Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée (CNC), Bois d’Arcy, France.

Selected Filmography

Jacques Sauvageot, a cameraman working on Albert Kahn’s project: Les Archives de la Planète came to shoot some short scenes to test the lenticular process. Restored in color for the Musée Albert Kahn by Alain Hairie in 1998.

Jacques Sauvageot, a cameraman working on Albert Kahn’s project: Les Archives de la Planète came to shoot some short scenes to test the lenticular process. Restored in color for the Musée Albert Kahn by Alain Hairie in 1998.

Technology

Characteristics and manufacture of the lenticular film

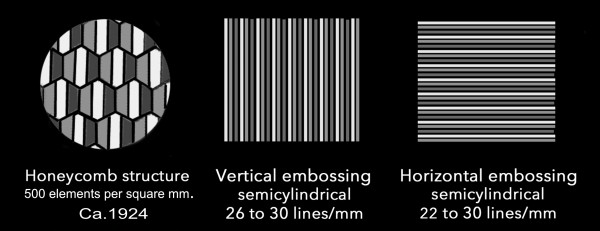

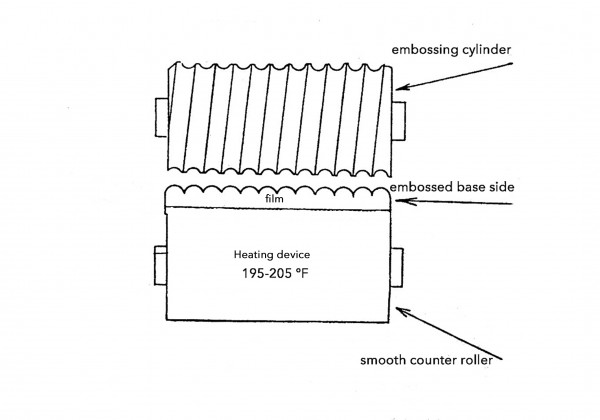

The film base was embossed prior to being coated in emulsion. The film base was run between an engraving cylinder and a smooth cylinder at a temperature of about 212 °F (100 °C). Early versions were produced with honeycomb embossing (approx. 500/square millimeter), which was later replaced by a linear embossing around 1924, consisting of hemispherical microlenses, arranged either vertically or horizontally. The lenticular elements were molded on the back of the film. The embossing pitch was variable: from 22 to 30 lines/mm. After the film base was embossed, a B/W panchromatic fine grain emulsion was coated. After the film had been exposed, it was developed by a B/W reversal process.

Shooting

The three-banded color filter was placed at the nodal point (optical center) of the lens. The inventor Rodolphe Berthon designed a special lens (manufactured by Optis) with a large aperture (50mm, f/2.5). “The presence of a banded filter in the aperture of the lens means that the lens must be used at full opening, if only to allow the light rays from each filter area to reach each lenticular element.” (Friedman, 1945).

The sensitivity of the film was considerably reduced (probably below 10 ASA) by the presence of the trichrome filter, which absorbed a considerable amount of light. Tests of hypersensitization with ammonia were attempted to increase the sensitivity of the film emulsion without much success.

As the image was recorded through the lenticular base, the resolving power was poor and caused color overlapping (crosstalk). Moreover, the optical system itself was far from perfect. If the image of the trichrome filter was correctly positioned in the center of the image, it was not the same on the edges, because the distance from the filter was greater and the image of the filter was therefore defocused (circle of confusion). This phenomenon caused an overlapping of the three primary colors, and thus a desaturation.

Projection and printing

The original reversal film could be projected without difficulty using the principle of the reversibility of light. The Keller-Dorian color film company organized very successful private screenings of the original film. George Eastman, who was in Paris in 1926, attended one of them and was enthusiastic, sending his engineers to Paris to study the validity of the Keller-Dorian process (see Kodacolor). But the Keller-Dorian company, in its haste to exploit its patents, had probably hidden the fact that the projected tests were not release prints, but were original camera reversal films.

The inability to make prints was indeed the Achilles heel of the lenticular process. Making prints on lenticular film had given rise to countless patents, but it had never been satisfactorily resolved.

Contact printing caused moiré interference effects, when the pattern of the master film was placed on top of the pattern of the duplicate.

Microscopic cross section of an embossed film, made by Rodolphe Berthon in 1914.

Cahiers des ingénieurs Pathé #33125. Film gaufré, CECIL & Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, Paris, France.

Different embossing types: Honeycomb, vertical and horizontal.

Diagram by François Ede.

Keller-Dorian embossing machine. Microscopic lenticules were pressed into the surface of the film base.

Diagram by François Ede.

Jardin Albert Kahn, The rose garden Boulogne, May 1928. Screen capture converted from a B/W reversal original to color through a trichrome filter.

François Ede collection, Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

Film technician Michel Richard setting up the optical system and the RGB filter on an optical printer at Hiventy laboratory in Paris, France in 2019. The optical system and trichrome filter were redesigned on the basis of Berthon and Keller-Dorian patents. As the film being copied had considerable shrinkage, the color copy produced on the optical printer was subsequently digitized, stabilized and graded.

Courtesy of François Ede.

References

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography. London: Chapman & Hall: pp. 317 & 324.

Ede, François (1995). Jour de Fête ou la couleur retrouvée. Paris: Cahiers du cinéma.

Ede, François (2013). “Un épisode de l’histoire de la couleur au cinéma: le procédé Keller-Dorian et les films lenticulaires” (“An Episode in the History of Film Colour: The Keller-Dorian Process and Lenticular Film”). 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze, 71 (Winter): pp. 187–202. https://journals.openedition.org/1895/4787

Friedman, Joseph S. (1945). History of Color Photography. Boston, MA: The American Publishing Company.

Ryan, Roderick T. (1977). A History of Motion Picture Color Technology. London: Focal Press.

Patents

Berthon, Rodolphe. 1908. Perfectionnements aux procédés de photographie trichrome. French Patent FR399,762, filed May 1, 1908, and issued July 1, 1909.

Compagnie Générale des Établissements Pathé Frères. 1913. French Patent FR472,090, filed July 28, 1913, and issued July 27, 1914.

Keller-Dorian Albert. 1913. Système de gravure pour projections photographiques reproduisant les couleurs de la nature. French Patent FR466,781, filed December 29, 1913, and issued May 23, 1914. https://data.inpi.fr/brevets/FR466781?q=keller-dorian#FR466781

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

François Ede is a cinematographer and a documentary filmmaker. He has restored several films shot with the Keller-Dorian process, including Jour de fête in 1994 and recently carried out the reconstruction and restoration of Abel Gance's La Roue (1923) for the Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé Foundation.

Bernard Tichit, Michel Richard, Simone Appleby, CNC Patrimoine and La Cinémathèque française.

Ede, François (2024). “Keller-Dorian”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.