A hybrid additive/subtractive three-color process, developed by John Eggert and Gerd Heymer of Agfa in Germany.

Film Explorer

Identification

Unknown

Agfa “Tripo” multilayer chromolytic (dye destruction/silver bleach) type emulsion.

Unknown

1

The subtractive three-color Pantachrom process successfully brought together the advantageous aspects of bipack, lenticular and silver dye bleaching methods – resulting in improved brilliance, and stability, of colors. The combination of the lenticular screen and color-band filters, contributed to a good separation of individual colors – whereas the silver dye bleach process used in printing allowed for a wide range of image dyes. Shots in daylight, and under carbon arc lighting, exhibited saturated blue tones, which could be tailored during shooting using a yellow-magenta-yellow color-band filter. Similarly, for incandescent light sources, a magenta-yellow-magenta filter was used. However, this intricate process was not free of the disadvantages of: insufficient color separation; haloing; color deficiency of depth of field; and focusing errors – all dependent upon the wavelength of incident light.

Unknown

The extant samples reveal that Pantachrom projection prints had an iron-blue toned, variable-area soundtrack, on a red-colored background.

Unknown

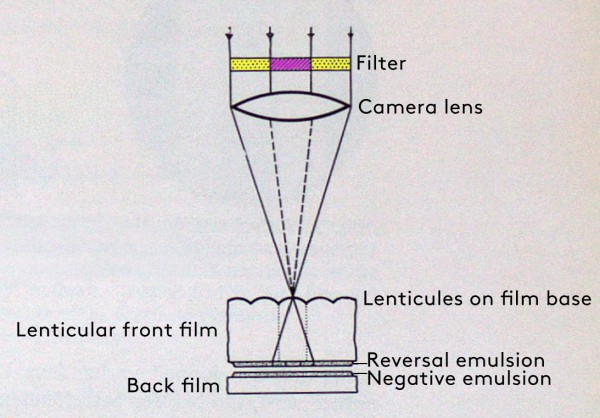

Lenticular bipack. The lenticular, orthochromatic reversal front film was sensitized for the blue and green parts of the spectrum, while the negative back film was panchromatic and sensitized to record the red part of the spectrum.

Unknown

History

In Farbe – Die Agfa-Orwo-Farbfotograhie, the seminal monograph by Erhard Finger, documents the development of multiple different natural color processes at Agfa – one of which was Pantachrom. This complicated process combined lenticular and bipack photography, with a silver dye bleach printing process similar to Gasparcolor. It was a progression of Agfa’s work on Linsenrasterfilm (16mm lenticular film for amateurs) during the early 1930s, and was under development at the same time as Agfa’s revolutionary Agfacolor negative–positive process.

Agfa had been researching lenticular film since 1928, and expanded its research with development of the two-color Ufacolor bipack process in 1930. Both of these processes had flaws. Ufacolor allowed for exposure ratings approaching that of B/W films, but attempts to extend it to three colors, by adding an extra emulsion layer to either the front, or back, of the double-coated print film, led to focus issues – while the lenticular system, by its very nature, required high light intensities. Combining these two principles provided a way to potentially overcome some of these flaws.

Meanwhile, between 1925 and 1930, work on a silver dye bleach process had also moved on with considerable success at Agfa. In December 1935, the label Pantachrom (previously employed for a duplicating stock) was introduced for the new lenticular-bipack process. By the mid-1930s, there was fierce competition between the lenticular processes offered by Agfa and Siemens (Opticolor) – with the latter’s exposure limitations, however, paving the way for Pantachrom. The Ufa film studio suggested a limited monopoly for the process in April 1936; and the first Pantachrom sound film was finished the following month.

However, Ufa's dissatisfaction with the pace of improvements with the process, as well as silver dye bleach patent concerns, led to further changes in the development of the special “Agfa Tripo” print film used in the process. The layer structure of the “Tripo” copy film (i.e. the same three-color-layer print stock used for Gasparcolor, which anticipated later chromogenic film, but was based on the chromolytic principle instead) was the subject of a patent dispute between Agfa and Gasparcolor Naturwahre Farbenfilme GmbH. Prior to this, Agfa and Gasparcolor had enjoyed a cordial working relationship, and they were collaborating on testing the Pantachrom process during 1935–6 – with close cooperation coming from Ufa's advertising department. Ultimately, Gasparcolor wanted to redirect its development efforts towards a recording process employing beam splitting; and, with the expiration of their contract with Agfa in 1938, the companies’ collaboration came to an end. In 1938, Agfa’s strategy was further complicated by advances in developing a chromogenic negative–positive process – demanding either a choice between one, or the other, or a combination of the processes (i.e. combining Agfacolor negative, with Pantachrom’s Tripo printing stock). By mid-1938, however, Ufa was ready for their own Pantachrom development and duplicating work. In October 1938, Agfa’s John Eggert publicly introduced the system with a talk and a screening, followed by the seminal 1939 paper in Veröffentlichungen des wissenschaftlichen Zentral-Laboratoriums der photographischen Abteilung Agfa series of publications.

The brilliant colors of Pantachrom were immediately appreciated by the advertising industry, and considerations for using it in the production of feature films emerged. However, an article published on October 22, 1938, in the Film-Kurier expressed skepticism about the future of the Pantachrom process – stating that it was only a bridging method, but not the ideal solution to the color film problem. Echoing similar opinions, Dr. Alfred Miller of Agfa stated that, “regardless of the outcome of the trials […] the Agfacolor process is the more promising”, as it was easier to produce, process, and thus to market, than Pantachrom. Such conjectures underline the fact that lower preference for the Pantachrom process was not only based on its color reproduction capability, but also on then-current market opportunities. This resulted in a lengthy internal dispute between Agfa’s scientific department, led by John Eggert, pursuing the Pantachrom process; and the technical-scientific department, under the supervision of Gustav Wilmanns, working on the Agfacolor process.

After conducting comprehensive comparative tests, at the beginning of 1939 it was finally decided to prioritize the Agfacolor negative–positive process as the cinematographic color process for feature film productions. However, between 1938 and 1939, a number of commercials, animation films and short documentaries were filmed using this process.

Selected Filmography

An animated commercial, for 4711 Eau de Cologne.

An animated commercial, for 4711 Eau de Cologne.

A documentary demonstration film, apparently a compilation of various subtractive and additive color processes

A documentary demonstration film, apparently a compilation of various subtractive and additive color processes

A “Culture film” (popular science documentary), in two parts.

A “Culture film” (popular science documentary), in two parts.

An animated commercial.

An animated commercial.

A “Culture film” in two parts.

A “Culture film” in two parts.

A “Culture film”.

A “Culture film”.

Technology

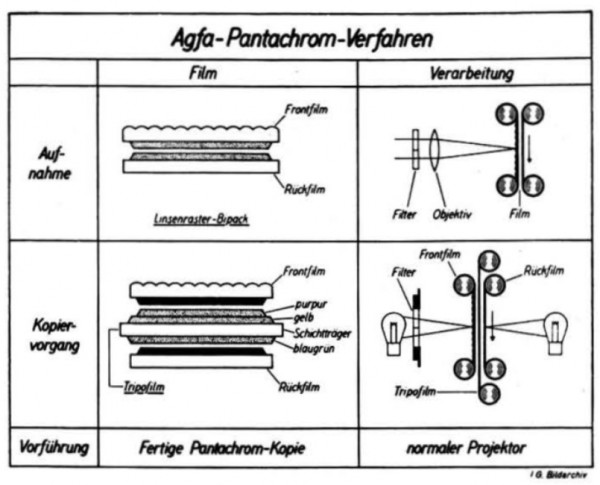

The short-lived, and difficult to categorize, Pantachrom process may seem like a curiosity, with little lasting impact today. However, the process remains historically and didactically intriguing. It united principles of bipack motion photography (employing green and blue sensitized lenticular front film with red-sensitized back film, along with two-color band filters) for recording, and eventually contact-duplicating, the three color records – captured with said bipack – onto a print stock with three emulsion layers. In the latter printing step, the process combined the silver dye bleach process for two of the primary colors, with iron-blue toning of a conventional emulsion for the third primary – essentially bringing together two very different basic principles for both three-color recording (lenticular and bipack) and printing (chromogenic and toning), respectively.

Filming

As described by Eggert and Heymer, a lenticular bipack was employed in photography, with two strips of film sandwiched together in the film gate, emulsion-to-emulsion. The film was shot in a bipack camera where special attention was paid to the film transport, pressure, and registration of the bipack film for optimal results. The front B/W lenticular reversal film was sensitive to blue and green light, while the back B/W negative film was predominantly red sensitive. Both the front and back films of the bipack were optimized for reduced transmittance, to curtail the adverse effects of halation (diffusion of light).

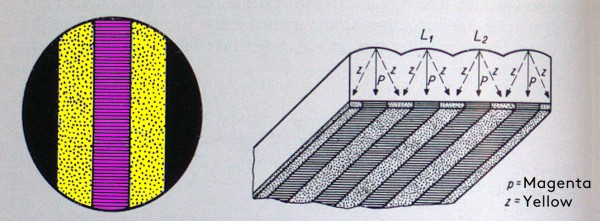

Although working according to a two-color principle, the band filter attached to the camera lens employed three alternating yellow-magenta-yellow filters – resulting in alternating green and blue rows of color separation of roughly the same width. Following the additive principle, this use of the yellow (red + green) and magenta (red + blue) filter bands, allowed red light to pass through the front lenticular reversal film unaffected to reach the back negative film, ensuring the recording of the red part of the spectrum. This filter arrangement could also be altered to magenta-yellow-magenta bands – depending on whether the shooting used daylight, or carbon arc light sources, to optimize sensitivity. Furthermore, the lenticular front recording film was produced by a casting process that produced a 43µm spacing of the vertical cylindrical lenses – which was 54% larger than the 28µm spacing of 16mm Agfacolor lenticular film – combining enhanced color separation with the higher spatial resolution afforded by the 35mm stock.

The front lenticular recording film of the bipack was processed as a B/W reversal film to produce a positive image. This resulted in improved contrast of the screen process’ lines, and better compensation for color losses that were caused due to light scattering in the emulsion layers. The back recording film was developed akin to a usual negative. The sensitivities of the emulsion layers were adjusted to harmonize for both daylight and carbon-arc photography, as per shooting conditions. Any remaining differences were compensated for in the copying process.

Printing

After shooting, each of the color separations recorded on the bipack film were precisely contact printed onto the designated layers of the Agfacolor Tripo copy film (which contained two layers of emulsion on one side of the film and another layer on the reverse side) using subtractive principles. From the front lenticular recording film, the blue separation, intended for the red-sensitive yellow layer of the Tripo film, was copied with red light; and the green separation, intended for the blue-sensitive magenta layer of the Tripo film, was copied with blue light. The red separation recorded in the back negative of the recording film was subsequently copied to the layer on the reverse side of the Tripo film using blue light. In this case, the color of the light used for copying was not directly related to the color of the resulting dyes. These printing light wavelengths were intricately chosen in order to avoid interferences between the different layers of the Tripo copy film. The directionality of the copying light striking the front film, optimal placement of the copying filters, and accurate registration of the film during the copying process, were all critical to achieve the desired results.

Following the silver dye bleaching process, the developed silver in the yellow and magenta dye layers of the Tripo film were bleached out, without affecting the unexposed silver bromide. Therefore, these areas represented a positive color image identical in proportion to the developed silver, removed in the process of bleaching and fixing. The rear emulsion of the Tripo was subsequently toned using iron blue, which was opaque in the infrared spectrum. This conveniently solved the problem of sound reproduction prevalent in subtractive processes of the time – which resulted from the transparency of the organic dyes in the red and the near-infrared spectrum. Although the Pantachrom process used the same Agfa Tripo film that had been developed for the Gasparcolor process, Gerd Heymer suggested that the lengthening of the processing time caused by the iron blue toning was compensated for by the simplified development of the backing layer – and, additionally, produced higher luminosity and color stability.

By early 1939, the sensitivity of the bipack films had further been improved, and the brilliance and light stability of the “Tripofilm III” led to considerable interest from the advertisement industry, with 98 copies ordered for a cologne commercial, and two hundred for a cigarette one, respectively – yet a comparative analysis, from January 1939, proved it somewhat inferior to Technicolor. Regardless of further chemical improvements, Pantachrom had to yield to the Agfacolor process and the comparative ease of its recording.

The bipack recording film, in which Z and P indicate the yellow and magenta stripes on the filter F, while A and R indicate the front lenticular and the back negative film, respectively.

Eggert, John & Gerd Heymer (1939). “Das Agfa-Pantachrom-Verfahren”. Veröffentlichungen des wissenschaftlichen Zentral-Laboratoriums der photographischen Abteilung Agfa, 15:6: pp. 46–64.

A bipack camera with the magazine on the top containing the front and the back recording films interleaved together.

Graphic representations of lenticular bipack filter with a magenta strip in the middle, flanked by two yellow strips (left); and (right) the superimposition of yellow filter images in the lenticular front recording film, in which both the right yellow filter image designated by the lens L1, and the left one by the lens L2, get recorded on the same side of the layer.

Graphical representation of the filming (Aufnahme) and copying (Kopiervorgang) stages of the Pantachrom process.

Eggert, John & Gerd Heymer (1939). “Das Agfa-Pantachrom-Verfahren. Ein Aufnahme- und Kopierverfahren für subtraktiven Farbenfilm”. Forschungen und Fortschritte. Nachrichtenblatt der Deutschen Wissenschaft und Technik, 15:4 (Feb.): pp. 49–51.

References

Anon. (1928a). “Nitralicht im Filmatelier”. Der Kinematograph, 22:1102 (Apr.): p. 32.

Anon. (1928b). “Die Verwendung der Glühlampen für Kinoaufnahmen”. Der Kinematograph, 22:1144 (Aug.): p. 144.

Anon. (1939). “Progress in the Motion Picture Industry. Report of the Progress Committee for the Year 1938”. Journal of the SMPE, 33 (Aug.): pp. 123–5.

Alt, D. (2011). “Der Farbfilm marschiert!”: Frühe Farbfilmverfahren und NS-Propaganda 1933-1945. Munich: Belleville: pp. 53–4, 160–5.

Beyer, F., G. Koshofer & M. Krüger (2010). UFA in Farbe. Technik, Politik und Starkult zwischen 1936 und 1945. Munich: Collection Rolf Heyne: p. 51.

Cauda, E. (1938). “Il cinema a colori. Quaderno mensile”. Roma: Bianco e nero, 2:11: pp. 69, 74–7.

Eggert, John & Gerd Heymer (1938). “Ein Zweipackverfahren für subtraktive Dreifarbenkinematographie. Agfa Pantachrom-Verfahren”. Die Kinotechnik, 20:12: p. 323.

Eggert, John & Gerd Heymer (1939a). “Das Agfa-Pantachrom-Verfahren. Ein Aufnahme- und Kopierverfahren für subtraktiven Farbenfilm”. Forschungen und Fortschritte. Nachrichtenblatt der Deutschen Wissenschaft und Technik, 15:4 (Feb.): pp. 49–51.

Eggert, John & Gerd Heymer (1939b). “Das Agfa-Pantachrom-Verfahren”. Veröffentlichungen des wissenschaftlichen Zentral-Laboratoriums der photographischen Abteilung Agfa, 15:6: pp. 46–64.

Finger, Ehrhard (2014). “Linsenraster Bipack (Pantachrom) – Kinefilm”. In Farbe: Die Agfa-ORWO-Farbfotografie, pp. 100–15. Berlin, Hildesheim & Luzern: Fruehwerk Verlag.

Koshofer, G. (1966). “Fünfundzwanzig Jahre deutscher Farbenspielfilm”. Film – Kino – Technik, 20:10: pp. 259–62.

Meyer, K. (1940). “Die farbenfotografischen subtraktiven Mehrschichten-Verfahren”. Ergebnisse der angewandten physikalischen Chemie (Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig), 6:2: pp. 427–30.

Schultze, W. & H. Berger (1938). “Das Agfa-Pantachrom-Verfahren”. Kinetechnische Mitteilungen der Agfa, 3/4 (Dec.): pp. 3–7.

Patents

I. G. Farbenfilmindustrie Aktiengesellschaft in Frankfurt am Main. Photographisches Dreifarbenverfahren. German Patent DE583747C, filed May 5, 1931, and issued September 8, 1933. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/007190547/publication/DE583747C?q=DE583747C

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Ulrich Ruedel holds a doctorate in Analytical Chemistry. Following film preservation training, and work in the US, Netherlands and the United Kingdom, he is now Professor of Conservation and Restoration at the University of Applied Sciences (HTW), Berlin, teaching and researching preservation of the moving image.

Sreya Chatterjee is a scientific researcher and teaching assistant at the University of Applied Sciences (HTW), Berlin, and a doctoral student at Martin Luther University, Halle-Wittenberg. She holds a BA in Mass Communication and Film Studies, a Post-graduate Diploma in Film Editing, and an MA in Conservation and Restoration from HTW, Berlin.

Isabell Krek, University of Lausanne and the Timeline of Historical Film Colors for many of the references used.

Ruedel, Ulrich & Sreya Chatterjee (2025). “Pantachrom”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.