A subtractive colour process developed by Karl Grune, Otto Kanturek & Viktor Gluck in the United Kingdom.

Film Explorer

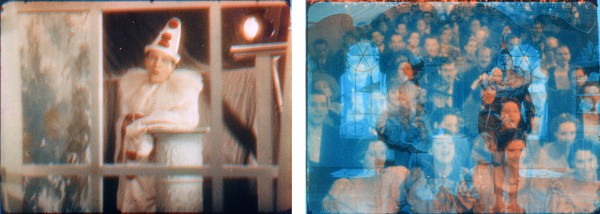

Steffi Duna, as Nedda Salvatini, in Pagliacci (1936), shot by chief cameraman Otto Kanturek and cameraman Alfred Black, and directed by Karl Grune. The Chemicolour process used orange and blue records, printed on either side of the film, to create a two-color image.

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom.

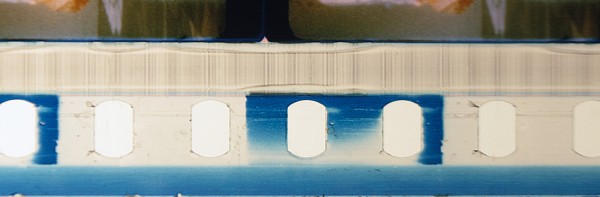

A test shot of an unknown woman. (c. 1935). British Chemicolour experimented with two alternative printing techniques: in this example, the edges of the film appear black; different to the blue edges seen in the release prints of Pagliacci.

Identification

21.0 mm x 15.2 mm (0.825 in x 0.600 in).

1.37:1 (released format); 1.19:1 (tests).

Duplitized (double-coated): one side toned blue; the other orange.

AGFA and a number, which possibly refers to an emulsion number – a system which AGFA began to implement in the 1930s. Blue blocks appear over two perforations every frame, most likely used to align the negatives for printing. This is not present in the surviving test films.

1

The process could not record the full visible colour gamut accurately. The colour range appears much better in surviving test strips than in the release prints, where orange and blue tend to dominate in most shots. The saturation also appears better in testing, than in release prints. Color fringing may be apparent within the image as a result of poor registration during printing. A duplicate, misaligned image in orange and blue is seen often at shot changes.

Colour Sequences photographed in Chemicolour.

Variable-density soundtrack, grey in colour (printed in B/W). Often very low-contrast, sometimes poorly masked or printed, giving a curvy appearance on both edges. This soundtrack was likely masked with varnish before the toning process.

21.50 mm x 18.00 mm (0.846 in x 0.708 in).

B/W, panchromatic.

Unknown

History

Chemicolour was developed by film director Karl Grune, cameraman Otto Kanturek and technician Viktor Gluck in the UK in the 1930s. It was a short-lived process, ambitiously developed in the hope of rivalling established colour processes, such as Technicolor and Cinecolor. On paper it looked like it could potentially rival these processes – projectors needed no special adaptation and cameras very little; less intense additional lighting (compared to B/W photography) than competing colour processes was needed to photograph it; and multiple duplicate prints could be made in a very short time. But despite being well received following its only release, Pagliacci (1936), the absence of solid backing from the British and American film industries, plus mounting financial troubles meant the process never had a chance to develop further.

In 1933, Hitler’s Nazi cabinet began taking control of German film studios, including Emelka and Ufa, where Grune, Kanturek and Gluck worked. The trio, who were all Jewish, suddenly found themselves out of work. They fled to England.

Grune arrived first, beginning work at Elstree Studios. Max Schach, a producer, Grune’s friend and fellow employee from Ufa, followed soon after and established a production base at Elstree in early 1934. Grune was already a well-established director with his films Die Straße (1923), Die Brüder Schellenberg (1926) which starred Conrad Veidt (who also fled to England in 1933) and Waterloo (1929), which was also produced by Schach. Grune joined Schach as a director but also as an associate, forming Capitol Film Productions together in July 1934. Capitol’s first film was Abdul the Damned (1935), a co-production with British International Pictures (BIP), which Grune directed. He was paired with Kanturek as cameraman, who had already been working in the UK for a couple of years at BIP. The two had worked together in Germany several times. They made another B/W film at Capitol before taking on the Chemicolour system.

Max Schach was keen to expand his business. From 1934 to 1936 he developed the ‘Max Schach Group’ which included another six production companies. One of these six was Trafalgar, the production company which would go on to make Pagliacci. Around this time, he also created British Chemicolour Ltd. Grune was appointed managing director, with Kanturek as cameraman and Gluck as a technician.

The exact specifics of Chemicolour's formulation remain unclear. The process was reportedly based on Ufacolor from the Ufa film studio in Germany, although Grune, Kanturek and Gluck appear not to have had any first-hand experience with the Ufacolor process before being exiled.

Chemicolour has been frequently described by historians as ‘the name under which the German Ufacolor Process was marketed in Britain’ (Street, 2012). Although it shares the same fundamental technology, Grune, Kanturek and Gluck undertook years of additional testing to make improvements to the process. They photographed around 40,000 ft (12,192m) of film – shooting interiors and exteriors in all weather conditions. A camera lens and negative-guiding mechanism was developed in the UK, independently from the original work on Ufacolor in Germany. Around mid-1935, Kanturek felt that the system had finally been perfected. In the same year, Publicity Picture Productions Ltd released a 43-minute version of Faust (1935) to launch the Spectracolor system. Developed in the UK, its origins also stemmed from the Ufacolor process, but was established independently from Chemicolour and shared no personnel. Spectracolor was similarly short-lived and was abandoned by the end of 1936. Its German ties, the war and the imminent construction of the UK Technicolor plant were all cited as reasons for its demise.

The film chosen to premiere Chemicolour was Pagliacci, an English-language adaptation of Ruggero Leoncavallo’s 1892 opera. The film was given a large budget, in part to pay for the colour photography, but also to compensate lead actor Richard Tauber, a renowned opera star who would draw in a broad audience for the new colour system. The film also starred Steffi Duna, who had already appeared in colour in the Technicolor films La Cucaracha (1934) and Dancing Pirate (1936). Production began on the film with close attention to the colour scenes, which were to open and close the film. Wendy Toye, choreographer on the film, spoke of Grune being “so engrossed in the colour of the colour sequences, that he handed it over to me to direct those sequences. And when I say direct, I mean rehearse them and direct it with the actors and then he put the cameras on it.” (Toye, 1991) The colour sequences were also shot in B/W as a back-up.

Colour printing systems were established at Elstree around August 1936. Kanturek stated that “copies can be produced in any number desired and in the same time as black and white prints, yet without injury to the quality of photography or colour” (Kanturek, 1937: p. 106).

Around the same time, Chemicolour was first demonstrated at Elstree Studios. About 1,200 ft (365.76m) of film was screened – mostly outdoor subjects of European locations and indoor costume shots. The tests were well received. The American trade journal Motion Picture Daily reported “very true color values” (Allan, 1936a).

Pagliacci was released in England in December 1936 to mixed reviews. Motion Picture Daily called it “box-office material of a classic”, praising the colour as “a pleasant surprise. Nothing so good has been made from a British process before and plenty worse has been sent from America” (Allan, 1936b). However, The Film Daily labelled it as “very creaky and laborious” but did approve of the colour stating it was “very effective, done in soft sepia effect and the colors very true and pleasing to the eye” (The Film Daily 1938e).

Following the release of Pagliacci, development of the Chemicolour system continued, with a patent being filed for improvements to the camera system in July 1937. The printing systems were also now fully operational.

With a solid system behind them, Grune and Schach eyed the American market. In late 1937, Grune travelled to America looking for a location for a printing plant, similar to the one established at Elstree, but on a larger scale. Kanturek and Gluck would help establish the process and train staff, once a facility was found. While in Hollywood, Grune attracted the attention of former studio mogul William Fox and hoped to tempt him out of retirement to support the project. Preliminary funding was seemingly secured in Chicago and rumours circulated that the Kromocolor plant in New Jersey was to be Chemicolour’s American home, secured by a bid from Fox’s associates. However, the bid fell through and shortly after, it was reported that William Fox was “no longer identified with British Chemicolor” (Motion Picture Daily 1937b). Grune continued his efforts to launch Chemicolour in America, but nothing tangible ever came to pass.

While Grune was selling in America, Chemicolour was due to be used on the British film Over She Goes (1937) – with Kanturek providing the cinematography – but the film was eventually released in B/W only. Meanwhile, it was reported that production company Trafalgar was working on 24 educational and travel shorts using the Chemicolour system, but none of these films have been found. It is possible the films were never produced, as mounting financial problems began to impact Schach’s companies.

Pagliacci was released in America on October 11, 1938, again to mixed reviews. Around the same time, Schach and his companies were facing financial and legal difficulties, which had been approaching since late 1937. This situation was unfolding while Grune was drumming up trade in America and was the likely cause for the collapse of nascent deals around the American Chemicolour plant. The legal woes were a big scandal at the time, the fallout spreading to impact other British studios and producers.

By December 1938, British Chemicolour was in receivership. Trafalgar and Schach’s other companies were also failing. Schach soon lost control of everything, resigned and retired shortly afterwards. Grune co-produced one more film, then retired and joined Schach in Bournemouth. Kanturek continued as a cinematographer until 1941, when he sadly died in a plane crash while filming aerial shots. Gluck continued to live in England until his death in 1957, but had no recorded credits beyond 1934. British Chemicolour was officially dissolved in 1951.

Selected Filmography

Various colour tests of the Chemicolour process. A print survives at the BFI National Archive.

Various colour tests of the Chemicolour process. A print survives at the BFI National Archive.

B/W feature with colour inserts. Prints survive at the BFI National Archive and in a private collection.

B/W feature with colour inserts. Prints survive at the BFI National Archive and in a private collection.

Technology

Only incomplete descriptions have been found for the Chemicolour process, mostly from Otto Kanturek’s own explanation in The Journal of the Association of Cine-Technicians (Kanturek, 1937). As the article might be considered as advertorial for the process, it is difficult to verify if his descriptions are a true and accurate depiction of the Chemicolour process. No documents or technical diagrams have been located to demonstrate how the camera worked, or how the negatives and positives were developed. Only printing tests and release prints have been found. The description of the process below is based on Kanturek’s article, the limited descriptions from the time, and analysis of the prints found in the BFI National Archive collection.

Chemicolour has been described as two-colour, three-colour and four-colour in different publications during its development and use – and by later historians. Kanturek described the process himself as “a subtractive process based on the four spectral colours of the colour spectrum (Yellow, Red, Green and Blue) and is produced by a means of genuine photographic galvanochemic system” (Kanturek, 1937: p. 106). He continued: “the negative is sensitised to the four colours, and is exposed to complementarily, so that after development of the negatives, which are controlled exactly by means of a sensitometer so that they remain equal in intensity and density, the actual print produces the same natural complementary colour picture which was photographed.”

Any camera could be used, adapted with “colour corrected lenses” and a device that could guide “several negatives” through the camera (Kanturek, 1937: p. 106).

To save the optical soundtrack from any potential loss of definition, it was coated with a thin layer of varnish, to prevent it from being bleached and dyed along with the picture. The contrast of the surviving soundtrack was incredibly low and poorly masked, leading to wavily bleached margins. Despite the low contrast, the soundtrack is still sufficiently audible.

Historians have surmised that Chemicolour used much of the same technology as Ufacolor, but it was evidently revised independently, given its differing appearance to Ufacolor. Ufacolor used an AGFA bi-pack negative and a duplitized (double-coated) positive mordant-toned with iron and uranium – for orange and blue respectively. It is possible Chemicolour used a similar process. No Chemicolour negatives have been found, but positives are printed on duplitized AGFA stock. Interestingly, no contemporary press from the 1930s mentions any links with Ufa, or Ufacolor.

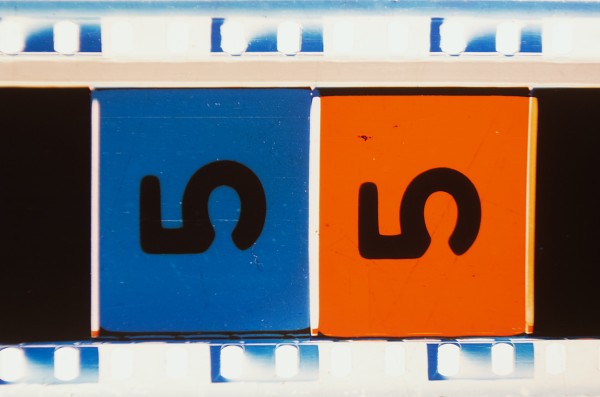

Ufacolor – a two-colour system – has been incorrectly described as ‘four-colour’ in the past, similarly to the descriptions of Chemicolour. Release prints of Pagliacci look similar to Ufacolor, but appear orange and blue rather than the reds and blues of Ufacolor. The countdown leader on prints of Pagliacci has both orange and blue frames for each number, possibly to aid with printing.

Trade papers from the time reported that Chemicolour was developing a four- and five-colour system around the time of Pagliacci’s release. The colour in the surviving prints of Pagliacci is inconsistent across prints. Some have better contrast, but most are somewhat washed out. All lean much more towards orange and blue, than red and blue. Some shots are out of register and almost all cuts between shots exhibit a distracting printing error. The focus is soft in all prints, with the colour-fringing often exaggerating this.

The tests that survive at the British Film Institute are much richer in colour, which may have been achieved by means of a four-colour process, like the one Kanturek describes. As they would have been processed on a smaller scale, there was probably a greater opportunity to fine tune the colour, resulting in a more balanced colour image, compared to the mass-produced prints. The perforation area in the tests also differs from those in the prints of Pagliacci. The film edges appear black, whereas the edges of the Pagliacci release prints are clear with blue blocks. The reason for the difference is unknown, but could be due to changes in the process over time.

Poorly masked B/W soundtrack on a 35mm print of Pagliacci (1936).

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom.

Countdown leader from a print of Pagliacci (1936). All numbers in the countdown are repeated twice, once in blue, once in orange, possibly to aid the line up of negatives for printing.

Pagliacci (1936). Poor registration resulting in fringing (left); and a printing error at a shot change (right).

References

Alicoate, Jack (ed.) (1938). “Color Processes”. In The Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures, Jack Alicoate (ed.), p. 1080. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc.

Allan, Bruce (1936a). “Television Intrigues U.K.: Values in New Color Seen”. Motion Picture Daily, 40:58 (Sep. 8): p. 1.

Allan, Bruce (1936b). “Overseas Previews – Pagliacci”. Motion Picture Daily, 40:150 (Dec. 26): p. 2.

Arnau, Frank (1933). Universal Filmlexikon. London: London General Press.

Boorne, Henry W. (1935). “Why Not a Stock Company?”. Film Pictorial, 8:198 (December 7): p. 40.

Brown, Simon (2012). “Technical Appendix”. In Colour Films in Britain: The Negotiation of Innovation 1900–1955, Sarah Street, pp. 265–266. Basingstoke, Hampshire: BFI/Palgrave Macmillan.

Coe, Brian (1981). The History of Movie Photography. London: Ash & Grant.

Collinson, Naomi (2003). “The Legacy of Max Schach”. Film History, 15:3: pp. 376–389.

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian, Major (1951). Colour Cinematography. London: Chapman and Hall.

Film Daily (1936a). “New Color Process London”. The Film Daily, 70:25 (July 30): p 12.

Film Daily (1936b). “New Color System London”. The Film Daily, 70:59 (Sep. 9): p. 71.

Film Daily (1937). “Further Delay is Likely in Kromocolor Takeover”. The Film Daily, 72:66 (Sep. 17): p. 2.

Film Daily (1938a). “Karl Grune Here to Set Up British Chemicolor Branch”. The Film Daily, 73:90 (April 19): pp. 1 & 8.

Film Daily (1938b). “Chemicolor Finance Deal Is Nearly Set”. The Film Daily, 73:101 (May 2): pp. 1 & 5.

Film Daily (1938c). “Chicago Money to Finance Chemicolor Lab. on Coast”. The Film Daily, 73:127 (June 2): pp. 1 & 3.

Film Daily (1938d). “Grune Plans Early Return to Effect U. S.”. The Film Daily, 74:57 (Sep. 8): pp. 1 & 4.

Film Daily (1938e). “A Clown Must Laugh”. The Film Daily, 74:84 (Oct. 17): p. 7.

Gough-Yates, Kevin (1991). “The European Filmmaker in Exile in Britain 1933-1945”. PhD thesis, The Open University.

His Majesty’s Stationary Office (1951). “Companies Act 1948”. The London Gazette (Feb. 16): p. 859.

Kanturek, Otto (1937). “A.C.T. Inventor Talk – Otto Kanturek on British Chemicolour”. The Journal of the Association of Cine-Technicians, 2:7 (Oct. 1936–Jan. 1937): pp. 106–107.

Kinematograph Publications (1940). “Bankruptcies, Liquidations, etc.”. The Kinematograph Year Book 1940, p. 190. London: Kinematograph Publications Ltd.

Klein, Adrian B. (1937). “Colour Consolidates Its Position”. The Journal of the Association of Cine-Technicians, 73.

Lobban, Grant (2004). The BKSTS Illustrated History of Colour Film. London: British Kinematograph Sound and Television Society.

Low, Rachael (1985). Film Making in 1930s Britain. London: Allen and Unwin.

Motion Picture Daily Inc. (1937a). “Report Fox Behind Sale of Color Lab”. Motion Picture Daily, July 14,: p. 1.

Motion Picture Daily Inc. (1937b). “Sale of Kromocolor Ordered Cancelled”. Motion Picture Daily, November 9: p. 7.

Quigley, Martin (1937). “Buy Kromo-Color Englewood Laboratory”. Motion Picture Herald, July 17: p. 36.

Steen, Al. 1938. “Color”. In The Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures, edited by Jack Alicoate, 65. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc.

Street, Sarah (2012). Colour Films in Britain: The Negotiation of Innovation 1900–1955. Basingstoke, Hampshire: BFI/Palgrave Macmillan.

Toye, Wendy (1991). Interview by Linda Wood and Dave Robson. BECTU, June 17, 1991 (accessed June 25, 2024). Audio, 03:30:00. https://historyproject.org.uk/interview/wendy-toye.

Wood, Linda (1986). British Films 1927–1939. London: BFI Library Services.

Patents

British Chemicolour Process Ltd. Improvements to toothed reels for motion picture. French Patent FR823944A, filed July 5, 1937, granted January 1, 1938. https://patents.google.com/patent/FR823944A/en 1938-01-28

Compare

Related entries

Author

J. M. Fernandes is an archivist at the BFI National Archive. Fernandes has a particular interest in early colour systems and has previously written an article on Technicolor II for Sight and Sound. Fernandes also contributed stills to FIAF’s expanded edition of Harold Brown’s Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification (2020).

Fernandes, J. M. (2024). “British Chemicolour”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.