A subtractive two-color process, developed in the UK by Albert Hopkins and Reginald Wyer of Publicity Pictures.

Film Explorer

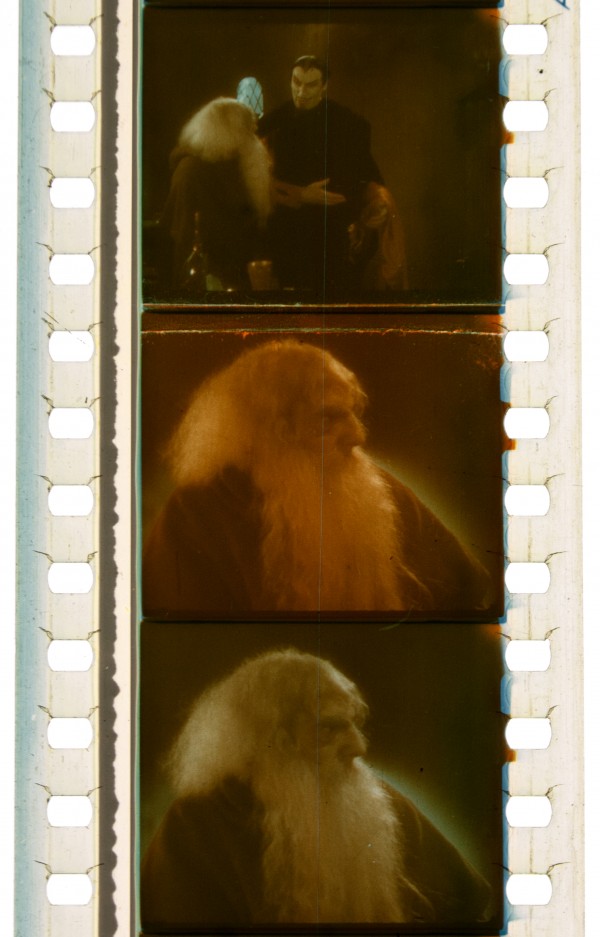

Anne Ziegler, as Marguerite, in Faust (1935). She starred alongside Webster Booth, who played the title role in this short, directed by Albert Hopkins. A 35mm colour print, on AGFA Dipo Stock (double-coated with emulsions on both sides of the base).

FI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom. Photograph by J. M. Fernandes.

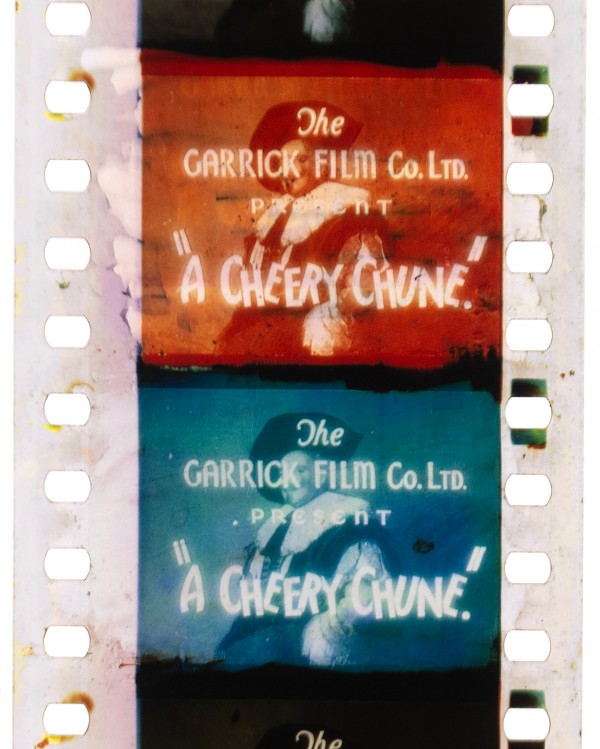

A shot from the animated advertising film, The Gay Cavalier (1935). The copy has inconsistent colour printing, is missing a soundtrack and has shots that are not sequential – suggesting this was a test print.

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom. Photograph by J. M. Fernandes.

Identification

22.0mm x 18.0mm (0.866 in x 0.709 in).

Duplitized (double-coated), dye-toned blue-green on one side, and red-orange on the other. Fixed with a mordant.

AGFA in blue, or GEVAERT BELGIUM in black or yellow. Dark rectangular markings, and other protruding shapes, are found in the perforation area of every frame – these were probably for aligning the negatives during printing.

1

The process could not record the full color spectrum accurately, with blues and reds appearing more prominently in images. Colors tend to be duller in live action, and more vibrant in animation. Occasional color misregistration in the first frame following a shot change.

Photographed in Spectracolor

Variable-area, unilateral soundtrack – grey in color.

Unknown

Bipack

Unknown

History

Spectracolor was a two-colour process, similar to the German Ufacolor system. It was used in the UK by Publicity Pictures who produced it in-house at their Bushey studios, Hertfordshire, during the 1930s, for shorts and advertising films. Spectracolor shared some similarities with Chemicolour, which was also based on the Ufacolor process, but was developed and marketed separately.

Publicity Pictures was founded in 1925, by director Albert Hopkins (often credited as A.E.C. Hopkins) and cinematographer Reginald Wyer. The company’s main focus was advertising films, which often included animation provided by Laurie Price.

Publicity Pictures saw the influx of colour systems in the early 1930s as an opportunity to distinguish its output from its competitors’. Hopkins and Wyer created the Spectracolor system to realise their colour projects. Spectracolor used AFGA bipack negative film, which was also used by the Ufacolor system. However, there is no known connection between Ufacolor and either Publicity Pictures, or Spectracolor.

In 1933, Publicity Pictures launched new studios in Bushey, to the north of London, fully equipped for sound, shooting colour and for laboratory work. They introduced Spectracolor with two films: an animation short, Morris May Day (1935), advertising the Morris Motors company; and the 45-minute live-action short Faust (1935), based on the Charles Gounod opera of the same name (1859). Faust was made in six weeks and premiered at the Curzon Cinema in Mayfair, London, in March 1935 – with Morris May Day screening before it. Reviews described Faust as a “praiseworthy attempt” (The Era, 1935), but criticised the colour, noting: “the only colours discernable were blue-green and a colour which gradually changed as the film proceeded from brown to orange” (Kinematograph Weekly, 1935).

Publicity continued using Spectracolor in a series of animated advertising shorts titled “Cheery Chunes” – of which, Morris May Day became the first in the series. Other “Cheery Chunes” included The Midshipman (1935) and The Gay Cavalier (1935), both of which advertised Worthington beer. Publicity worked almost exclusively in advertising throughout 1936 and 1937, but did lend their services to other companies. In partnership with Publicity Pictures, Carnival Films used Spectracolor for its short Railroad Rhythm (1937), which Hopkins directed; as did L. C. Beaumont in his comedy for Viking Pictures, The Beauty Doctor (1937).

Towards the end of 1937, Reginald Wyer left Publicity Pictures, to focus on a career as a cinematographer. Laurie Price also left, around this time, to work for fellow animator Anson Dyer. By now, Publicity had sold its Bushey studio and began to move away from using Spectracolor as a system. They produced at least one more live-action advertising film in Spectracolor, titled Land of the Four Kings, for Cow and Gate (a British dairy products and baby food company), which was in production, November 1937. For their short Homes of Great Britain (1939), Publicity used Dufaycolor, further suggesting that Spectracolor had been abandoned.

As war broke out in 1939, Publicity Pictures (now renamed National Interest Picture Productions Limited) switched to producing government training films, which often included animated elements. All of their titles during this period were B/W. The move away from colour films and Spectracolor may have been due to a number of factors. There would have been difficulty importing AGFA bipack films from Germany after the start of World War II, although some Gevaert products remained available for making prints. In addition, after Publicity sold the Bushey studio, they outsourced printing to other labs who were evidently not capable of dealing with Spectracolor. This resulted in a legal dispute with one lab, where Spectracolor negatives had been damaged beyond repair. The lack of a competent laboratory for printing may have been a factor in dropping the process.

There is some evidence that further experimentation with Spectracolor may have occurred. In January 1956, the British Film Institute acquired two copies of the Spectracolor live-action short Fashion Sketches (1936), advertising Bestway patterns and starring Binnie Hale. The copies were catalogued by Harold Brown, with assistance from Major Adrian Cornwell-Clyne. One copy was Spectracolor, but the second copy was on a double-coated Eastman stock from 1940. Brown noted “a two-colour image is produced, apparently by dye-toning and the soundtrack is toned blue” (Brown, 1956). Notes from Cornwell-Clyne added that the film was in a can marked “Tonachrome” (Brown, 1956). It is possible that this was a later experiment to further develop Spectracolor – and, possibly, rebrand it as Tonachrome. Eastman stock may have been used in place of AGFA or Gevaert stocks, due to the German stocks being less accessible during wartime.

Selected Filmography

Animated advertisement short.

Animated advertisement short.

Colour live-action short.

Colour live-action short.

Animated advertisement short.

Animated advertisement short.

Live-action advertisement short.

Live-action advertisement short.

Live-action short. Also known as Faust Fantasy.

Live-action short. Also known as Faust Fantasy.

Animated advertisement short.

Animated advertisement short.

Animated sections in a live-action, advertisement short.

Animated sections in a live-action, advertisement short.

Advertisement live-action short.

Advertisement live-action short.

Animated advertisement short.

Animated advertisement short.

Animated advertisement short.

Animated advertisement short.

Colour live-action short.

Colour live-action short.

Technology

Documented technical information on Spectracolor is very limited, in both a historical and contemporary context. No technical diagrams or patents relating to Spectracolor have been located and few documents or articles have been discovered. Only projection prints, and test prints, have been found – no negatives.

The following description of the technology is largely based on a 1935 Kinematograph Weekly article, Adrian Cornwell-Clyne’s description in Colour Cinematography (1951), BFI Catalogue Notes, and examination of the surviving copies at the British Film Institute.

Spectracolor was a two-colour subtractive process. Bipack negatives (two strips of film sandwiched together in the camera – one negative capturing green-blue, the other capturing red-orange) were exposed in a Vinten camera, which was equipped with a bipack gate and a custom magazine. Positive prints were double-coated (or duplitized, with emulsions on both sides of the base) dye-toned blue-green on one side, and red-orange on the other – these were then fixed with a mordant. Prints were on both AGFA and Gevaert Belgium stocks.

Spectracolor, Ufacolor and Chemicolour are often linked by historians, but there is no evidence, yet located, to confirm that they are the same process, albeit rebranded.

The soundtracks on surviving copies are variable-area, printed in B/W. To save the soundtrack from any potential loss of quality, this part of the film strip was coated with a thin line of varnish, to prevent it from being bleached and dyed, during processing, along with the picture. Varnishing of the soundtrack also appears in Chemicolour prints.

The quality of surviving Spectracolor prints is generally good. Although the process could not capture a full range of colours, reds and blues appear decent – particularly in animation. The prints are sharp, with fair contrast. Registration issues and fringing are not found in Spectracolor prints, a problem which frequently occurred in Chemicolour prints. Colour differentials could appear in the first frame following some shot changes.

A printing error shows the two colour records, isolated, in a test print of The Gay Cavalier (1935).

The Gay Cavalier (1935), left, on Gevaert Belgium stock, and Faust (1935), right, on AGFA. The Gay Cavalier appears very different from Faust – largely due to it being badly printed, leading to uneven colouring which extends into the perforation area. The perforation area has also suffered from mold damage. The two prints have different markings in different locations within the perforations, with the AGFA marks appearing less prominent than the Gevaert marks.

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom. Photographs by J. M. Fernandes.

Colour differentials in the first frame of a shot in Faust (1935).

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom. Photograph by J. M. Fernandes.

References

Alt, Lutz (1986). “The Photochemical Industry: Historical Essays in Business Strategy and Internationalization”. Ph. D. Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/4426306.pdf (accessed: 23 October 2024).

Aman, Leigh (1937). “Says Anson Dyer”. The Journal of the Association of Cine-Technicians, 2:8 (Feb.–Mar.): pp.143-4.

Anon. (1935). “Speed Combined with the Highest Possible Quality”. The Journal of the Association of Cine-Technicians, 1:3 (Nov.): p. 74.

Anon. (1978). “Notice to Creditors”. The London Gazette, 47452 (January): p. 1307.

Brown, Harold (1956). Personal correspondence from Harold Brown (with notes from Major Adrian Cornwell-Clyne) to Ernest Lindgren (March 7, 1956). Acquisitions paperwork. BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom.

Brown, Simon (2009). “Colouring the Nation: Spectacle, Reality and British Natural Colour in the Silent and Early Sound Era”. Film History, 21:2 (Early Colour: Part 2): p. 144.

Brown, Simon (2012). “Technical Appendix”. In Street, Sarah, Colour Films in Britain: pp. 282–3.

Coe, Brian (1981). “In All the Hues of Nature”. The History of Movie Photography. London: Ash & Grant, p. 129.

Cornwell-Clyne, Major Adrian (1951). “Spectracolor”. Colour Cinematography. London: Chapman and Hall, pp. 342–3.

Era, The (1935). “Faust” (review by “R. B. M.”). The Era (March 20): p. 3. London: Unknown Publisher

Gordon, Kenneth (1935). “Spectracolor”. The Journal of the Association of Cine-Technicians, 1:1 (May): p. 9.

Hale, Peter (2017). A History of British Animation (last modified 2017). http://s200354603.websitehome.co.uk/main/BAHpreface.htm (accessed December 14, 2024).

Hopkins, A. E. C. (1937). “Secrets of Cartoon Techniques”. The Journal of the Association of Cine-Technicians, 2:7 (December–January): p. 96.

Kinematograph Weekly (1935a). “Spectracolor: Ingenious Process” (review by “R.H.C.”). Kinematograph Weekly, 1457 (March 21): p. 61.

Kinematograph Weekly (1935b). “Making Colour Cartoons”. Kinematograph Weekly, 1467 (May 30): p. 50.

Kinematograph Year Book (1937). “Films Registered Under the Act”. Kinematograph Year Book. London: Kinematograph Publications Ltd., p. 112.

Low, Rachael (1985). “Colour Films”. Film Making in 1930s Britain. London: Allen and Unwin, p. 107.

SMPTE (1954). “The Production of Motion Pictures in Color 1930–1954”. The Journal of the SMPTE, 63:4 (Oct.): pp. 138–40.

Street, Sarah (2012). Colour Films in Britain. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Patents

None found.

Compare

Related entries

Author

J. M. Fernandes is an archivist at the BFI National Archive. Fernandes has a particular interest in early colour systems and has previously written an article on Technicolor II for Sight and Sound. Fernandes also contributed stills to FIAF’s expanded edition of Harold Brown’s Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification (2020).

I would like to thank James Layton and Crystal Kui for their help and guidance throughout, as well as those who reviewed my entry and gave their valuable feedback.

Fernandes, J. M. (2025). “Spectracolor”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.