An enhanced version of Technicolor’s dye-transfer process, reintroduced in the late 1990s.

Film Explorer

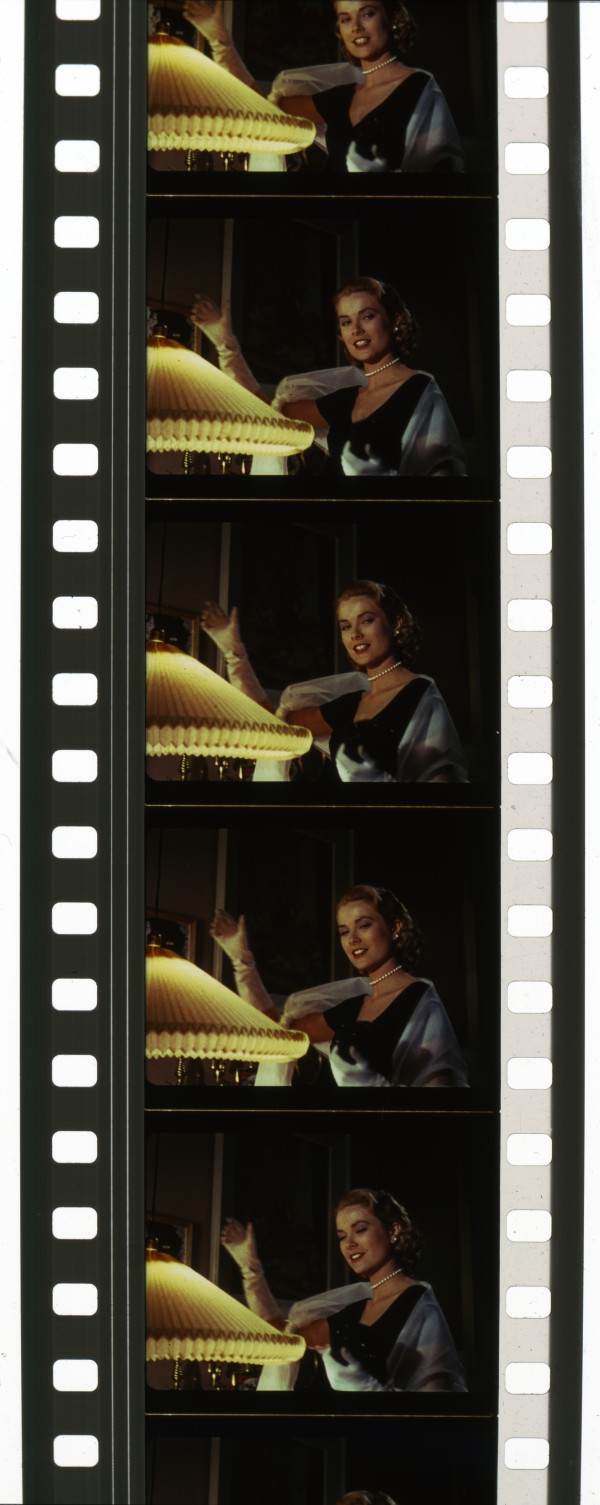

Samples frames from Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz’s 1999 restoration of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). Approximately 40 35mm dye-transfer prints were made for this reissue.

NBCUniversal, Universal City, CA, United States / Robert Harris, Bedford, NY, United States.

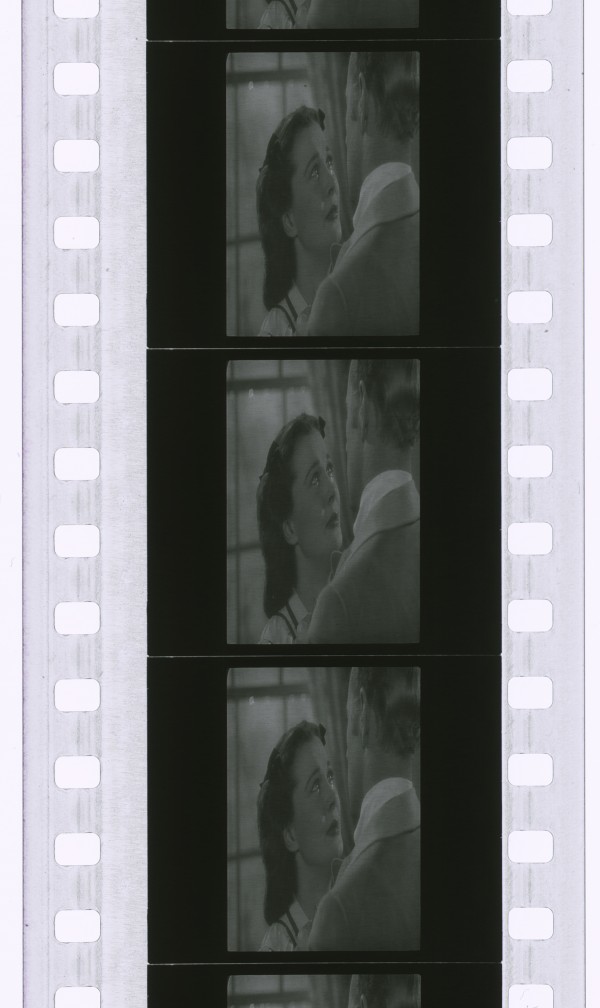

The large-scale 60th anniversary theatrical reissue of Gone with the Wind (1939) required over 200 dye-transfer prints from Technicolor. These 35mm prints contained an optically-converted, squeezed anamorphic image so they could be screened in multiplexes normally unable to screen a 1.37:1 image. Black bars appeared on either side of the frame to maintain the original aspect ratio.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

Technicolor imbibition

None

1

Compared to standard Eastmancolor prints, Technicolor dye-transfer show prints are richer in color, with greater contrast and shadow detail.

Technicolor was credited for laboratory work on all of the titles released with imbibition show prints, however there was no specific credit on screen referencing the dye-transfer printing.

This printing method was compatible with all commonly-used sound technologies of the period, including optical sound, DTS, SDDS and Dolby Digital. These tracks were printed in B/W, rather than dye.

Color negative, most commonly Eastman or Fuji.

History

Technicolor’s revival of its dye-transfer process (also known as Technicolor process #6) was commercially available for a brief period of six years, roughly from 1997–2002, produced solely from the company’s North Hollywood laboratory, located on Universal Studio’s lot. The small team at Technicolor devoted to the reintroduction of imbibition (IB) printing were devotees of the classic imbibition printing process – created by the company in the early-1930s – that had run its commercial course by the end of the 1970s. That earlier period of classic Technicolor IB printing was deservedly known throughout the world of cinema as one of (if not) the greatest examples of motion picture color in cinema history.

The reintroduction of dye-transfer printing in the late 1990s was limited to a select group of noteworthy productions – but proved unsustainable due to its small print runs, higher price point and technical issues.

It should be remembered that the paradigm for theatrical distribution and exhibition changed dramatically in the later half of the 1970s – in great measure prompted by the implementation of significantly larger print runs as seen with blockbusting movies from the New Hollywood directors, such as Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977). Eastmancolor prints, manufactured by Technicolor on new bespoke high-speed printers, had print volumes in the hundreds and premiered “day and date” across North America. Both films did, however, receive a few IB dye-transfer “show prints” from Technicolor London. (This new paradigm for theatrical exhibition grew dramatically over the following decades and peaked around 2010 with the day-and-date global theatrical release of the last Harry Potter films that employed nearly 20,000 35mm Eastmancolor prints, populating screens around the world.)

From the mid-to-late 1970s onward, Technicolor was ideally situated to take full advantage of the explosion of global cinema, while more quietly servicing the equally dramatic growth of home entertainment by manufacturing and duplicating VHS tapes and DVDs en masse. With the continued stability in its revenues and profitability through the 1980s, the company was able to devote the requisite funds required to explore relaunching a dye-transfer line from its Hollywood operations.

Based on the passionate regard for the storied process from major American and international filmmakers, Technicolor began feasibility studies in the early-1990s to reintroduce “the greatest name in color”. The company’s head of operations in Hollywood, Ron Jarvis, was committed to the reintroduction of IB printing and tasked company technical director/engineer Frank Ricotta to evaluate the realities of bringing back IB printing. A key member of the engineering team advising on IB printing was Keith Burnham who had earlier overseen dye-transfer printing at Technicolor West Drayton, near London. Further, Jarvis rehired famed Technicolor color scientist Dr. Richard Goldberg to oversee the effort. Ricotta and Goldberg negotiated with the Chinese government to repurchase the Technicolor printing equipment, originally based at Technicolor, West Drayton, that had been sold to the Chinese in the late 1970s. Earlier, Goldberg had consulted with the Chinese lab in Beijing having visited the facility with producer Jeffrey Selznick in the later part of the 1970s.

The goal was a quality product that satisfied filmmakers’ needs, that could also be scaled-up sufficiently to meet demand for massive day-and-date print runs at a cheaper price point than standard Eastmancolor prints. (In the early 1970s, it was not uncommon for up to 800 dye-transfer prints to be made from one set of matrices, greatly decreasing the cost of release prints). Ricotta explained at the time that the new process yielded sharper, less grainy images than conventional color positive prints, as well as “an extended tone scale resulting in blacker blacks, whiter whites and improved color rendition” (Desowitz, 1997).

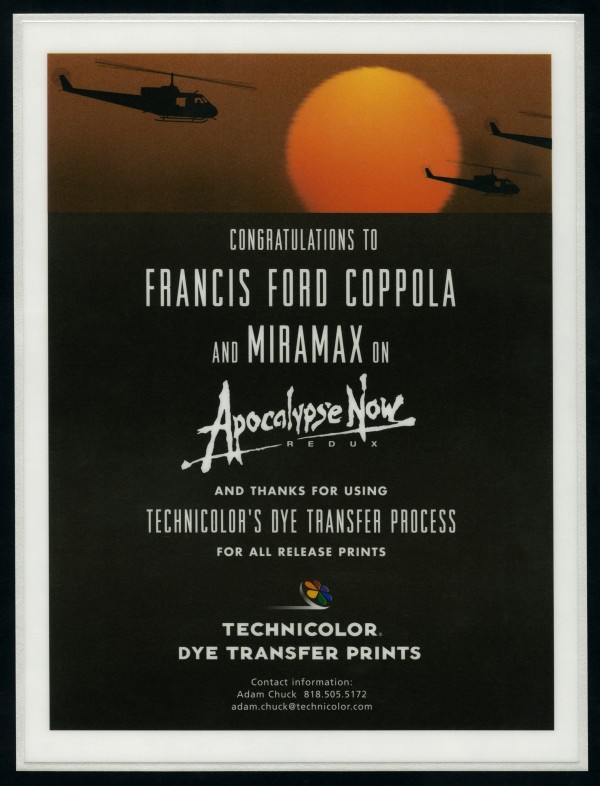

The films released on dye-transfer prints between 1997 and 2002 were an interesting group of new features, with a smattering of restorations of earlier classics: for director Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now Redux (2001), as noted by cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, Technicolor’s Rome lab had originally planned on producing select dye-transfer prints for the film’s initial release in 1979 – but the film’s post-production was seriously delayed, and by release Technicolor had shut down its dye-transfer line in Rome.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) was fully restored by Robert Harris and James Katz for Universal Pictures and printed in dye-transfer under the supervision of Dr. Goldberg. The film’s initial release in 1954 was assumed to have been printed in dye-transfer, as were other Hitchcock color classics – but this was not the case for Rear Window for a myriad of reasons. Other classics restored and printed in dye-transfer included Gone with the Wind (1939) and The Wizard of Oz (1939). New films given dye-transfer release or show prints included: director Warren Beatty’s Bulworth (1998), Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line (1998), Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor (2001) and Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla (1998).

In parallel with the relaunch and demise of IB printing in the early 2000s, Technicolor was investing heavily in the transition to digital workflows with the creation of two divisions devoted to digital intermediate color-grading, and a separate group created to produce DCP masters and copies for digital projection that the world of theatrical exhibition would soon embrace. Despite the company's intentions to scale-up print volume to meet day-and-date release demands the industry desired, Technicolor's dye-transfer revival was hampered by quality-control issues and technical failures – as well as the impending industry transition to digital exhibition. As a result, the revival was not fully implemented as intended. It was ultimately used for only small print runs of show prints and classic film reissues.

35mm prints of Apocalypse Now Redux (2001). A dye-transfer show print (left) and an Eastmancolor release print (right). Note the soundtracks on the left edge are printed in B/W on the dye-transfer print.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States / George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

A plaque commemorating the dye-transfer print run of Apocalypse Now Redux (2001).

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Technicolor President Ron Jarvis (left) and Eastman Kodak's President of Professional Motion Imaging Dick Ashman (right), c. 1996. They are likely signing an agreement for Kodak to manufacture and supply polyester blank stock for Technicolor’s dye-transfer revival.

Selected Filmography

Several hundred dye-transfer prints were made.

Several hundred dye-transfer prints were made.

The first film released with Technicolor’s new dye-transfer prints. Show prints only.

The first film released with Technicolor’s new dye-transfer prints. Show prints only.

Re-released in the United States with approximately 20 dye-transfer prints in 2001.

Re-released in the United States with approximately 20 dye-transfer prints in 2001.

Some test prints were made c. 1996.

Some test prints were made c. 1996.

Approximately 250 dye-transfer prints were made.

Approximately 250 dye-transfer prints were made.

Over 200 dye-transfer prints were made.

Over 200 dye-transfer prints were made.

Only two dye-transfer prints were made.

Only two dye-transfer prints were made.

Approximately 40 dye-transfer prints were made for the restored 1999 reissue.

Approximately 40 dye-transfer prints were made for the restored 1999 reissue.

Only one dye-transfer print was made.

Only one dye-transfer print was made.

TV movie. One dye-transfer print was made.

TV movie. One dye-transfer print was made.

One 35mm test print of the 1996 restoration was made.

One 35mm test print of the 1996 restoration was made.

Re-released in the United States in 1998. Approximately 50 dye-transfer prints were made.

Re-released in the United States in 1998. Approximately 50 dye-transfer prints were made.

Technology

The fundamental technology and methodology employed in Technicolor’s dye-transfer revival was much the same as Process #5 (Technicolor prints from color negatives): three color separation matrices (one for each dye record: yellow, cyan and magenta) were extracted from the original camera negative (OCN) and then optically printed on custom matrix stock. The B/W separations were then imbibed with a specific color then contact printed – in three separate passes – on blank release print stock, that, upon final application of all three hues, would aggregate into the remarkable color rendition Technicolor IB printing was internationally acknowledged for. As noted by director Francis Ford Coppola, the dye-transfer process was more akin to lithographic printing popularized in the 1930s principally for magazine advertising (Coppola, 2014)

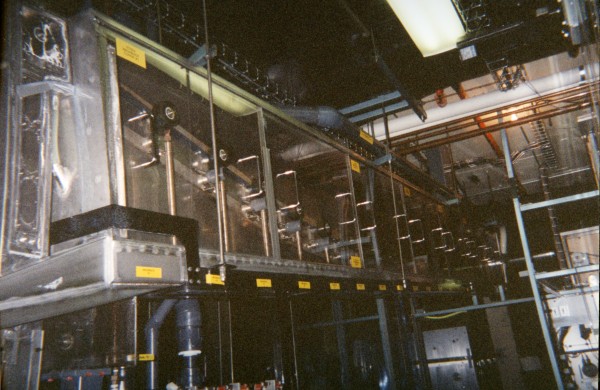

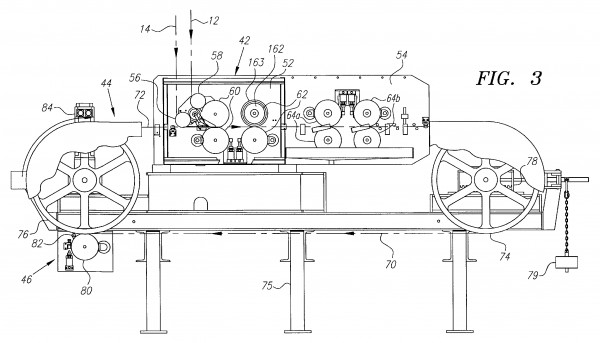

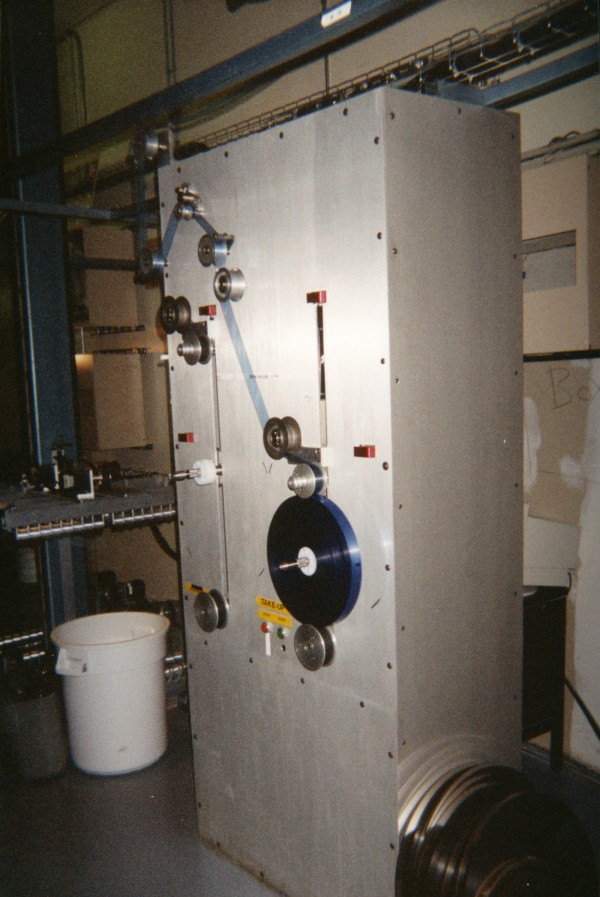

To make this dye-transfer revival viable, it was designed by Dr. Goldberg to be fully automated and to operate continuously: 24-hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week. A prototype machine was built, as a proof of concept. Per electronic engineer Hal Rattray, who built all of the computerized systems: “It was a single machine with all of the basic elements but required passing the blank stock through the machine three times changing the matrix and dye for each pass. It worked and a few show prints were done on it.” Subsequently, two full-scale printing machines were constructed that had a combined footprint of approximately 100,000 ft2 (9,300m2), occupying “virtually all of the third floor and a large part of the second floor” of the Technicolor laboratory on the Universal lot (Rattray, 2024). These vast machines operated continuously, without requiring matrices to be swapped out at the end of each pass, as with the prototype. Dyes were computer-controlled with input received by the color timers (graders). Dye amounts could be carefully controlled from scene to scene as needed, while transfer speeds reached around 800 ft (243.84m) per minute. A dye-transfer print reportedly cost $0.15 per ft, compared to $0.20 per ft for an Eastmancolor print (Haines, 2000).

Despite the scale and ambition of Technicolor’s plans – reportedly costing tens of millions of dollars – the dye-transfer revival failed. The newly introduced polyester blank stock manufactured by Eastman Kodak proved problematic, resulting in flaking of the dyes which then gummed-up 35mm projectors. And Technicolor was unable to produce hundreds of prints from each matrix, as it had been the case in the 1970s. While solutions to these issues could have been addressed with time, Technicolor was fighting an uphill battle. The Hollywood studios remained committed to the status quo and were not inclined to support filmmakers’ desire to present their films with any more than a limited number of dye-transfer prints, or a few token, yet exquisite, “show prints”. As demand withered, so too did the company’s resolve to support the required IB infrastructure.

Dye-transfer matrix element from Gone with the Wind (1939). Matrix and blank stocks were manufactured by Eastman Kodak for Technicolor.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Each matrix passed through a dye spray cabinet, where either yellow, cyan or magenta dye was applied, before the matrix moved on to the roll tank, where the image was transferred to the blank in its specific color, before the process began again for the next dye.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

The roll tank and pinbelt loop, the most crucial part of the dye-transfer process, where the dyed matrix and blank stock were pressed together and held in contact while the dyes were imbibed by the blank.

Jarvis, Ronald, Richard J. Goldberg, Frank J. Ricotta, Ronald W. Corke, Lawrence A. Curtis, Steven Garlick, David M. Gilmartin. Dye transfer apparatus and method for processing color motion picture film. US patent US6,002,470, filed September 9, 1997, and issued December 14, 1999.

The take-up for completed prints at the end of the process. An elevator to the rear allowed operators time to cut the film, change to another spindle, and restart the take-up without stopping the machine.

References

Coppola, Francis Ford (2014). Email correspondence with Robert Hoffman.

Desowitz, Bill (1997). “Film restoration more than ‘Rear Window’-dressing”. CNN Interactive. (December 11) (accessed October 18, 2024). https://web.archive.org/web/20221020014231/http://edition.cnn.com/SHOWBIZ/9712/11/rearwindow.restoration.lat/

Dootson, Kristy Sinclair & Zhaoyu Zhu (2020). “Did Madame Mao dream in Technicolor? Rethinking Cold War colour cinema through Technicolor’s ‘Chinese copy’”. Screen, 61:3 (Autumn): pp. 343–367.

Haines, Richard W. (2000). “Technicolor Revival”. Film History, 12:4: pp. 410–416.

Harris, Robert & John Belton (2000). “Getting It Right: Robert Harris on Colour Restoration”. Film History, 12:4: pp. 393-409.

Hoffman, Robert (2024). Alchemy in Technicolor. Medley Lane Scribes (self-published).

Rattray, Hal (2024). Email correspondence with James Layton, Crystal Kui and Rob Hummel (July 30).

Ricotta, Frank (c. 1998/99). Interview by Craig McCall (n.d.).

Ricotta, Frank (2013). Oral history conducted by James Layton, Shannon Fitzpatrick and Almudena Escobar Lopez (April 26). George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Sprocket School (2020). “IB Technicolor”. Sprocket School (April 23, 2020) (accessed 1 October 2024), https://www.sprocketschool.org/wiki/IB_Technicolor

Patents

Jarvis, Ronald, Richard J. Goldberg, Frank J. Ricotta, Ronald W. Corke, Lawrence A. Curtis, Steven Garlick, David M. Gilmartin. Dye transfer apparatus and method for processing color motion picture film. US patent US6,002,470, filed September 9, 1997, and issued December 14, 1999.

Jarvis, Ronald, Richard J. Goldberg, Frank J. Ricotta, Ronald W. Corke, Lawrence A. Curtis, Steven Garlick, David M. Gilmartin. Dye transfer apparatus and method for processing color motion picture film. US patent US6,094,257, filed October 13, 1999, and issued July 25, 2000.

Jarvis, Ronald, Richard J. Goldberg, Frank J. Ricotta, Ronald W. Corke, Lawrence A. Curtis, Steven Garlick, David M. Gilmartin. Dye transfer apparatus and method for processing color motion picture film. US patent US6,327,027 B1, filed July 24, 2000, and issued December 4, 2001.

Jarvis, Ronald, Richard J. Goldberg, Frank J. Ricotta, Ronald W. Corke, Lawrence A. Curtis, Steven Garlick, David M. Gilmartin. Dye transfer apparatus and method for processing color motion picture film. US patent US6,469,776 B2, filed June 15, 2001, and issued October 22, 2002.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Robert Hoffman served as Vice President of Marketing & Public Relations at Technicolor for 18 years. Earlier, for seven years, he was the head of Communications & Public Relations at director James Cameron’s award-winning Visual Effects studio, Digital Domain. He studied filmmaking at The American Film Institute, and in a career that spanned over 50 years, he was an award-winning educational documentary filmmaker as well as having worked for Warner Bros., Paramount, and 20th Century Fox in Marketing and Publicity. Most recently, Hoffman authored Alchemy in Technicolor – a personalized study of Technicolor’s greatest achievement in motion picture color.

James Layton, Rob Hummel, Craig McCall, and all of the blind peer reviewers.

Hoffman, Robert (2024). “Technicolor dye-transfer revival”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.