A subtractive three-color dye-transfer process that utilized equipment formerly used at Technicolor’s London laboratory.

Film Explorer

A 35mm dye-transfer print of Make Ten Million (1992). This sample print was made in 1993 for Technicolor Inc., part of a feasibility study related to Technicolor’s 1990s dye-transfer revival.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

A 35mm dye-transfer print of The Peacock Princess (1982).

Moving Image Research Collections, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, United States.

Identification

Variable

Dye-transfer prints. Blank stock made by the Baoding Film Stock plant.

Typically no text, however there is commonly dye spatter and streaking on the film’s edges, remnants from the dye-transfer printing process.

1

A full color image capable of high levels of saturation.

None

Optical soundtrack printed in black & white.

Variable

Chromogenic negative, typically Chinese Daidaihong stock. Some productions may have been shot using Eastmancolor or Agfacolor negatives. Matrices made by the Baoding Film Stock plant.

“DDH” is evident on Daidaihong negatives.

History

This technique (also known as dye-transfer and dye-imbibition) was operational at the Beijing Film Laboratory between 1978 and 1993. It was identical to the Technicolor V process used at Technicolor’s laboratories in Hollywood, London, Paris and Rome throughout the 1950s, 60s and 70s, and was installed by employees of Technicolor Ltd.—the British wing of the firm. However, the Beijing Film Laboratory was not part of Technicolor’s official laboratory network, and films printed using this process do not carry Technicolor credits.

In 1973 the Chinese government contracted Technicolor Ltd. to install IB machinery at the Beijing Film Laboratory that was identical to the equipment used in London (Yang and Feng). This contract was signed during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76) when Chairman Mao Zedong required a technology to mass produce color prints of propaganda films. During this period film production was largely, though not entirely, restricted to cinematic versions of the Yangbanxi, or ‘revolutionary model stage works’ (both ideological ‘models’ to be imitated by audiences, and ‘models’ that could be replicated by local performance groups). These ballets and operas were designed to spread Maoist ideology across China. All Yangbanxi featured vibrant color design and were most likely filmed using a combination of Agfacolor imported from East Germany, illicitly imported American Eastmancolor and Chinese daidaihong negative stock manufactured by the Baoding Film Stock plant from 1971 (Pang; Dootson and Zhu). From 1975 the Yangbanxi were printed using dye-transfer equipment that had been installed in Shanghai and Beijing based on Soviet models (Yang and Feng). However, Jiang Qing (Mao’s wife, in charge of cultural production) who oversaw the production of Yangbanxi, was a great admirer of Technicolor and it seems that, in combination with the improved efficiency and quality of Technicolor’s system, aesthetic concerns may have motivated the purchase of equipment from London (Dootson and Zhu). This coincided with Technicolor’s decision to cease dye-transfer printing at its various plants in the 1970s due to declining print runs. The installation of the machinery was overseen by Bernard Happé, the Technical Director of Technicolor Ltd. (Happé) and Wang Peifang, the director of the Beijing laboratory.

Technicolor IB equipment was never used to print any Yangbanxi however, as it was not operational until 1978, with a second machine installed in 1981 (Chen), by which point Mao had died and the Cultural Revolution had concluded (both in 1976). Furthermore, China’s new Chairman Deng Xiaoping was about to implement economic reforms in 1979 that would transform the landscape of filmmaking in China (Zhu and Nakajima; Yeh and Davis).

From the late 1970s to mid-1980s studios made films according to quotas set by the government-run China Film Corporation. Studios were not financially rewarded according to the number of people who saw their films (box office was an irrelevant metric for measuring viewership at a time when screenings were usually un-ticketed or free), but according to the number of prints they manufactured. This incentivized large print runs irrespective of audience demand. Technicolor’s IB process, capable of cheaply mass-producing large quantities of release prints, was perfectly suited to these conditions, producing an average print run of 250 per title by the early 1980s (Samuelson). By the 1980s and 1990s Beijing’s IB plant was manufacturing release prints of popular genre films, including comedies like Make Ten Million, historical epics like The Burning of Yuan Ming Yuan and fantasies like The Peacock Princess. Contrary to popular belief, it is unlikely the process was used to print films made by fifth generation filmmakers like Zhang Yimou. It seems the plant initially used a mix of blank and matrix materials supplied by Kodak and 3M before developing these materials domestically at the Baoding Film Stock plant. By 1979 all dye-transfer printing in China used domestically made blank and matrix stock (Di, 1980).

By 1993 however, the Beijing Film Laboratory saw a fifty percent drop in print runs and decided to discontinue the use of its IB system (Wang). This was due to the film industry’s gradual shift towards a more marketized system that had begun in the mid-1980s. As the Chinese film industry moved increasingly towards performance-related pay, local distributors began to choose the titles they wanted to screen instead of having them dictated by the government, disincentivizing the inflated print runs that had characterized the industry in previous years. Furthermore, the increasing import of international films, combined with a greater take-up of television, caused a severe decline in Chinese print runs that made the costly IB process uneconomical. Although Technicolor’s Hollywood plant negotiated to purchase back this equipment, it was only pin-belt related machinery that was acquired and shipped back to California for use in their IB revival of the 1990s (Anon, 1996).

Film can from the Beijing Film & Video Laboratory for a 35mm IB print of Make Ten Million (1992).

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

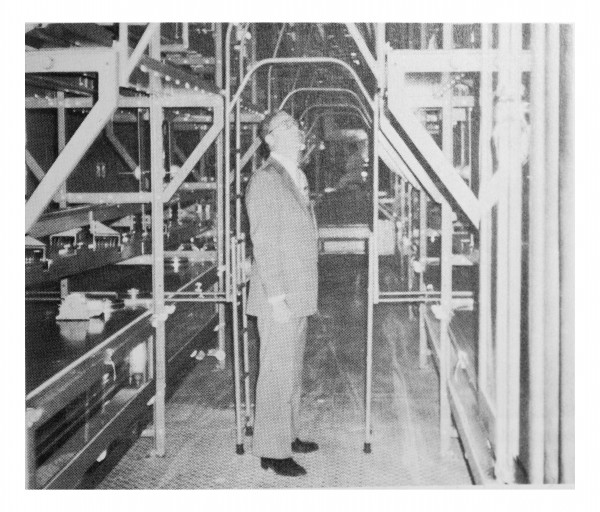

SMPTE President Robert M Smith inspecting the imbibition color processing and printing facility in the Beijing Central Laboratory.

W. D. Hedden, F. M. Remley, and R. M. Smith, ‘Motion-Picture and Television Technology in the People’s Republic of China: A Report’, SMPTE Journal 88, no. 9 (September 1979): 610–18.

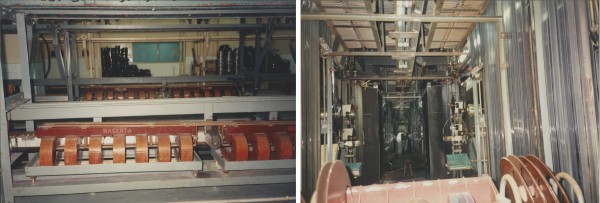

Photographs of the interior of the Beijing Film Lab in 1993.

Richard J. Goldberg Papers, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Selected Filmography

Live action feature. After the May Fourth Movement, the intellectuals Jian Sheng and Zijun, who pursued personal liberation, disregard the constraints of feudal society and fall in love.

Live action feature. After the May Fourth Movement, the intellectuals Jian Sheng and Zijun, who pursued personal liberation, disregard the constraints of feudal society and fall in love.

Live action feature. Film Adaption of Lao She’s novel. This story is set in old Beijing and depicts the tragic fate of Xiangzi, a rickshaw puller nicknamed "The Camel." The story reflects the suffering of the vast laboring population at the bottom of urban society and exposes the evils of the old social order.

Live action feature. Film Adaption of Lao She’s novel. This story is set in old Beijing and depicts the tragic fate of Xiangzi, a rickshaw puller nicknamed "The Camel." The story reflects the suffering of the vast laboring population at the bottom of urban society and exposes the evils of the old social order.

Live action feature. Film Adaption of Lao She’s drama. This film is set against the backdrop of the rise and fall of the Yutai Teahouse in old Beijing. It tells the story of the hardships and gradual collapse of life experienced by the ordinary people of China from the early 20th century to the eve of communist liberation.

Live action feature. Film Adaption of Lao She’s drama. This film is set against the backdrop of the rise and fall of the Yutai Teahouse in old Beijing. It tells the story of the hardships and gradual collapse of life experienced by the ordinary people of China from the early 20th century to the eve of communist liberation.

Live action feature. This film is adapted from the myth of the Dai ethnic group, telling the story of the prince Shao Shutun, who, guided by the Golden Deer, meets and falls in love with the Peacock Princess Namunuo'na.

Live action feature. This film is adapted from the myth of the Dai ethnic group, telling the story of the prince Shao Shutun, who, guided by the Golden Deer, meets and falls in love with the Peacock Princess Namunuo'na.

Live action feature. The film is set against the historical backdrop of the burning of the Imperial Palace by the Anglo-French forces, and tells the story of how Empress Dowager Cixi is transformed from an unnoticed young girl to the favored concubine of Emperor Xianfeng.

Live action feature. The film is set against the historical backdrop of the burning of the Imperial Palace by the Anglo-French forces, and tells the story of how Empress Dowager Cixi is transformed from an unnoticed young girl to the favored concubine of Emperor Xianfeng.

Live action feature. After the burning of the Yuanming Palace, the Ching Dynasty is in great disorder. Empress Dowager Cixi carries out Xinyou Coup d’ Etat’ and overthrows the opposition forces. The six-year-old master is enthroned and the “Reign Behind a Curtain” begins.

Live action feature. After the burning of the Yuanming Palace, the Ching Dynasty is in great disorder. Empress Dowager Cixi carries out Xinyou Coup d’ Etat’ and overthrows the opposition forces. The six-year-old master is enthroned and the “Reign Behind a Curtain” begins.

Live action science-fiction/exploitation film in which aliens crash-land on earth in the 1930s and assume human identities, only to discover years later a comic book has been made about them. In the present they attempt to kill the comic-book artist in New York.

Live action science-fiction/exploitation film in which aliens crash-land on earth in the 1930s and assume human identities, only to discover years later a comic book has been made about them. In the present they attempt to kill the comic-book artist in New York.

Live action feature. The film tells the story of Niu Dawei, who fantasizes about striking it rich, and the events that unfold after he inherits over 10 million yuan from his uncle.

Live action feature. The film tells the story of Niu Dawei, who fantasizes about striking it rich, and the events that unfold after he inherits over 10 million yuan from his uncle.

Live action feature. In the late Qing Dynasty, a young Mongolian man named Menghe does business in the capital city with his adoptive father Boyin. The prince of the grasslands, Bahawang, wants to take Menghe's fiancée for himself and conspires with the prince of the capital city, Zhang, to harm Menghe and his adoptive father. When their plan is exposed, Bahawang's men set fire to Boyin's wife, killing her. Menghe and the daughter of Qingfeng, a skilled martial artist, vow to return to their homeland for revenge. Menghe and Qingfeng's daughter, Longxia, return to the grasslands to seek vengeance and settle the blood feud, resulting in a tragic ballad of the grasslands.

Live action feature. In the late Qing Dynasty, a young Mongolian man named Menghe does business in the capital city with his adoptive father Boyin. The prince of the grasslands, Bahawang, wants to take Menghe's fiancée for himself and conspires with the prince of the capital city, Zhang, to harm Menghe and his adoptive father. When their plan is exposed, Bahawang's men set fire to Boyin's wife, killing her. Menghe and the daughter of Qingfeng, a skilled martial artist, vow to return to their homeland for revenge. Menghe and Qingfeng's daughter, Longxia, return to the grasslands to seek vengeance and settle the blood feud, resulting in a tragic ballad of the grasslands.

Reprinted in Beijing in 1993 as an experimental test for the 1990s American Technicolor dye-transfer revival.

Reprinted in Beijing in 1993 as an experimental test for the 1990s American Technicolor dye-transfer revival.

Technology

The process was identical to Technicolor’s method of making dye-transfer prints from chromogenic negatives, used at Technicolor’s plants in Hollywood, London, Paris and Rome.

The Beijing IB system was never used in combination with three-strip cinematography, which had not been in use since 1955 when the Hollywood and London unites retired their camera units. Regional film studios would shoot on color negative, and after editing was complete, local film laboratories would make an initial answer print on standard color stock, before sending final cut negative and soundtracks to Beijing for dye-transfer release printing (Happé, 1989).

Using filters, chromogenic negatives were transformed into three B/W color separation master positives carrying information for red, green, and blue color information respectively. These master positives were optically printed to make duplicate separation negatives that were then used to manufacture matrices. (In some cases, matrices were made directly from the camera negative). These matrices were developed to harden the gelatin in the most exposed areas of the image. Unhardened gelatin was washed off, leaving a gelatin relief image corresponding to the latent image on the film. Each matrix was passed through a dye-tank in the corresponding complementary color (the red record was dyed cyan, the green dyed magenta, and the blue record dyed yellow). A dyed matrix was held in register with a blank strip of film (coated in gelatin) by a metal pinbelt, and under pressure from the rollers in the roll-tank, the dye transferred from the matrix to the blank. The gelatin on the blank absorbed—or drank in—the dye, hence the name dye-imbibition. Each color was printed in turn onto the blank to reproduce the full spectrum.

Space Avenger (1989). 35mm Eastmancolor picture negative (left), B/W soundtrack negative (center), and dye-transfer print (right). The print was created from three color separation matrices derived from the Eastmancolor negative. The soundtrack was printed separately in B/W onto the blank film directly from the soundtrack negative. Note the yellow dye staining on the right edge of the dye transfer print. This film was produced in the United States, but dye-transfer release prints were made in China.

Academy Film Archive, Hollywood, CA, United States / The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

References

Anon. 1996. “Chinese pinbelt purchase”, Richard J. Goldberg Collection, Technicolor Archives, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York.

Chen, Bo. 2005. Zhongguo Dianying Biannian Jishi: Zonghe Juan (The Chronicle of Chinese Cinema: Comprehensive Volume), Beijing: zhongyang wenxian chubanshe: 818.

Di, Shijei. 1980. “The People’s Republic Of China: Addendum to The Progress Committee Report”, SMPTE Journal 89, no. 6 (June 1980): 468.

Dootson, Kirsty Sinclair and Zhaoyu Zhu. 2020. “Did Madame Mao Dream in Technicolor? Rethinking Cold War Colour Cinema through Technicolor’s “Chinese Copy””, Screen 61, no. 3 (1 September 2020): 343–67.

Happé, Bernard. 1989. Interview by Frank Littlejohn, Alan Lawson and Alf Cooper, 13 June 1989, made by the Broadcasting, Entertainment, Communications and Theatre Union Oral History Project (BECTU), https://historyproject.org.uk/interview/bernard-happe

Heckman, Heather, Lydia Pappas, Laura Major. 2024. “The Chinese Film Collection at the University of South Carolina’ in Global Film Colour: The Monopack Revolution at Midcentury Sarah Street and Joshua Yumibe eds., New Brunswick, N.J., Rutgers University Press, 2024), pp. 126-136.

Pang, Laikwan. 2012. “Colour and Utopia: The Filmic Portrayal of Harvest in Late Cultural Revolution Narrative Films”, Journal of Chinese Cinemas 6, no. 3 (January 2012): 263–82.

Samuelson, D.W. 1983. “Filming in China”, American Cinematographer 64, no. 5 (May 1983).

Wang, Peifang. 1993. Fax to Richard Goldberg, 29 October 1993, Richard J. Goldberg Collection, Technicolor Archives, George Eastman Museum, Rochester New York.

Yang, Haizhou and Shulan Feng. 1998. Zhongguo dianying wuzi chanye xitong lishi biannianji (Chronicle of Chinese Cinema Material Industrial System) (Beijing: Zhongguo Dianying chubanshe)

Yeh, Emilie Yueh-yu and Darrell William Davis. 2008. “Re-nationalizing China’s film industry: case study on the China Film Group and film marketization”, Journal of Chinese Cinemas, vol. 2, no. 1: 37–51.

Zhu, Ying and Seio Nakajima. 2010. “The evolution of Chinese film as an industry”, in Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen (eds), Art, Politics and Commerce in Chinese Cinema (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press): 25–28.

Patents

None

Preceded by

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Kirsty Sinclair Dootson is a Lecturer in Film and Media at University College London. She specializes in the material and technical history of modern color media. Her first book The Rainbow’s Gravity: Colour, Materiality and British Modernity was published in 2023. With Alice Lovejoy and Pansy Duncan she is co-editing the first volume dedicated to the history of film stock and has an essay on Technicolor’s global history in Global Film Color: The Monopack Revolution at Midcentury, Sarah Street & Joshua Yumibe (eds), (Rutgers University Press, 2024.)

Zhaoyu Zhu is a Teaching Fellow in Communication and Cultural Studies at the University of Nottingham, Ningbo, China. He is presently working on his monograph on the production of film technology in the Mao era. He has published articles on Screen and Journal of Beijing Film Academy (Chinese).

This entry is based upon an article originally published as Kirsty Sinclair Dootson and Zhaoyu Zhu, ‘Did Madame Mao Dream in Technicolor? Rethinking Cold War Colour Cinema through Technicolor’s “Chinese Copy”’, Screen 61, no. 3 (1 September 2020): 343–67. We are grateful to the journal’s editors for allowing us to reproduce a highly truncated version here.

Dootson, Kirsty Sinclair & Zhaoyu Zhu (2024). “Chinese imbibition prints (Beijing Film Laboratory)”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.