A dual-strip stereoscopic 3-D camera system developed and promoted by Milton Gunzburg in the early 1950s.

Film Explorer

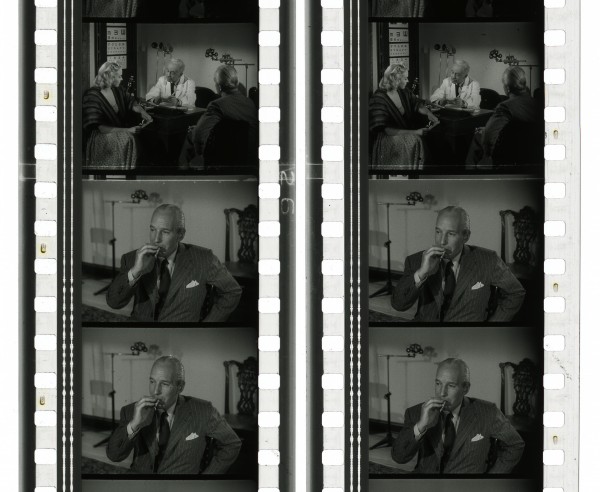

Actor Lloyd Nolan listens intently to an explanation of stereoscopy in the 1952 short M. L. Gunzburg Presents Natural Vision 3-Dimension. These left- and right-eye 35mm prints would have been projected in synchronization through polarizing filters with the images overlaid on the screen. The audience wore corresponding polarized glasses to decode the 3-D image.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Identification

15.24mm x 20.96mm (0.600 in x 0.825 in).

B/W or color (Anscocolor, Eastmancolor and Technicolor). Release prints used an unconventional emulsion orientation, with the emulsion facing the screen (B-wind emulsion orientation, rather than the standard A-wind).

2

Several Natural Vision releases were in color. These were shot on either Anscocolor, or Eastmancolor (WarnerColor), and these original prints now likely show signs of heavy color fading. Fort Ti (1953) and Devil’s Canyon (1953) were shot on Technicolor Monopack stock and released in IB Technicolor prints.

Filmed in Natural Vision Three Dimension.

House of Wax (1953) and The Charge at Feather River (1953) both featured WarnerPhonic sound. During these presentations, the left and right 35mm reels of picture were synchronized to the third reel of 35mm full-coat magnetic film containing left, center and right audio channels. The right-eye picture reel carried the rear sound effects on an optical track, while the left-eye picture reel contained a composite. mono optical track, for use by theaters not equipped for WarnerPhonic sound. (Anon., 1953c). For non-Warner Natural Vision releases, both left and right prints carried the same optical sound tracks. In this way, once all 3-D play-dates had been served, it was possible to "split" the print in order to service two 2-D playdates.

16mm x 22mm (0.630 in x 0.866 in).

B/W or color (Anscocolor, Eastmancolor and Technicolor Monopack).

History

After more than a year of development, the Natural Vision 3-D camera system was used to film Bwana Devil (1952), which became a surprise hit upon its premiere in Los Angeles at Thanksgiving that year. This ignited a brief, intense flurry of 3-D production and exhibition in Hollywood and elsewhere. Eight more Natural Vision features were made in Los Angeles between January and October 1953, while 40 other English-language features were made using competing 3-D systems during the same period.

In 1950, Milton Gunzburg, a former newspaper reporter and screenwriter, hoped to produce a modest feature film based on his screenplay Sweet Chariot, a story of young hotrod automobile enthusiasts (Higham, 1972). Seed money for the project came from sympathetic family members. Preliminary footage, taken at a race meet in B/W 2-D, was underwhelming. But Gunzburg, a dedicated photo hobbyist, was captivated by color stereoscopic slides made on the same occasion using a Stereo Realist consumer camera and subsequently decided to attempt production of his feature in stereoscopic 3-D. Inquiries led him to Friend Baker and Lothrop Worth, veteran camera technicians who had been experimenting with a single-strip stereoscopic device of their own design, called Stereo, designed for use with 16mm equipment (Gunzburg, 1953).

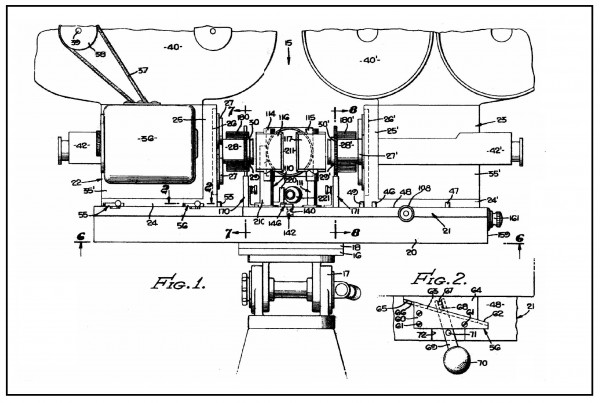

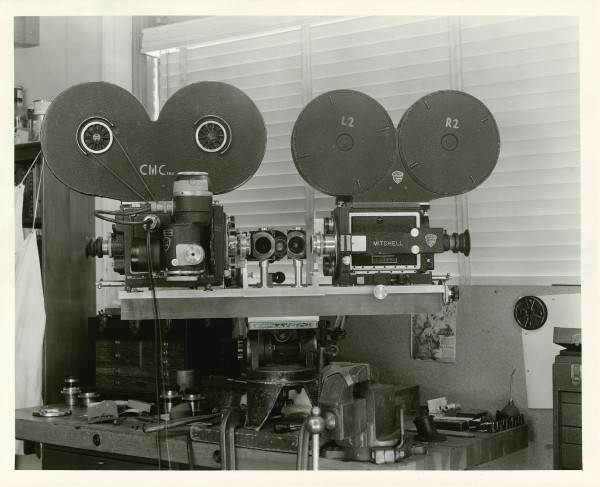

Gunzburg saw merit in Baker and Worth’s basic concept, but he wanted a system suitable for large-screen projection in ordinary cinemas, using standard 35mm equipment. A further stipulation was that the system should be, as nearly as possible, compatible with established 2-D studio production procedures. Baker and Worth, along with their colleague O. S. Bryhn, mounted two Mitchell NC studio cameras on a rigid base in a face-to-face configuration. Paired mirrors on micrometer mounts diverted the optical axes 90 degrees, resulting in a lens separation (or interaxial) of 3.5 in (88.9mm), slightly greater than the average human interpupillary distance of 2.5 in (63.5mm). By sacrificing a variable interaxial, which some other 3-D experimenters held to be essential, Natural Vision could guarantee that its rig would remain in precise alignment through all the expected rigors of studio, or location, filming (Gunzburg, 1953). Gunzburg set aside his proposed film Sweet Chariot to concentrate solely on promoting and developing this new system, now called Natural Vision 3-Dimension.

Unpaid options on the system taken by 20th Century-Fox and MGM were eventually dropped, while discussions with other studios and producers ultimately proved fruitless. Gunzburg finally connected with radio-wunderkind-turned-filmmaker Arch Oboler, who was enthusiastic about making a low-budget feature in Natural Vision (Higham, 1972). Begun under the working title The Lions of Gulu, the film was renamed Bwana Devil. Financing proved piecemeal, and Oboler was forced to woo additional investors on a near-daily basis, to secure the funds to complete the picture. Production proceeded fitfully through June and July 1952 (Zone, 2002).

Despite an all-round critical drubbing, Bwana Devil reportedly sold more than 600,000 tickets in three weeks at two theaters in Los Angeles, during the 1952 holiday season, resulting in a sudden, massive interest in Natural Vision and other competing 3-D systems throughout Hollywood (Paramount Theatres, 1953). Bwana Devil was acquired by United Artists in January 1953 for wide distribution over the next several months (Anon., 1953a).

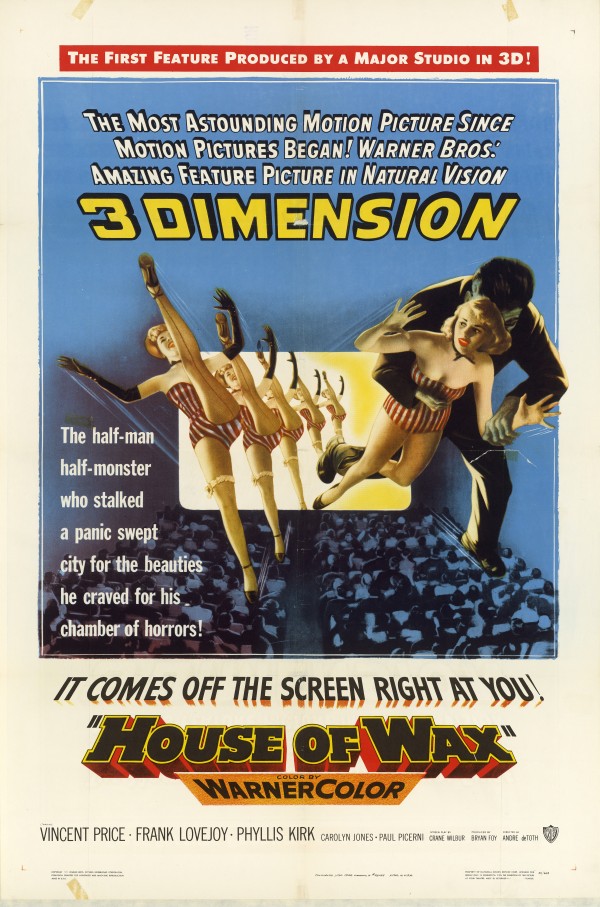

Warner Bros. then broadly announced its plans to start producing films in 3-D and signed a deal with Natural Vision. Warners commenced photography on House of Wax in January 1953 (Higham, 1972) – the completed film went on to outperform Bwana Devil at the box office when it opened in April 1953, becoming the most commercially successful 3-D film of the 1950s (Anon., 1961). Warners followed this up in July 1953 with The Charge at Feather River in Natural Vision – another tremendous commercial hit – and later the independent pick-up The Moonlighter in Natural Vision, which did only modest business. Later 3-D films from Warners used the studio's own proprietary camera rig, designed and built by Al Tondreau, head of the studio’s camera machine shop.

Other studios and independent producers hired Natural Vision rigs and camera crews for their own productions: among them, Columbia (Fort Ti); RKO (Devil's Canyon); Albert Zugsmith (Top Banana); Edward Small (Southwest Passage); and Ivan Tors (Gog). In the meantime, many studios built their own proprietary camera rigs, including Paramount, Columbia, Universal, MGM, 20th Century-Fox and Allied Artists. Yet more 3-D camera systems were available for hire from independent vendors such as Loucks & Norling Studios, Stereo Techniques Ltd, Stereo-Cine, Cinecolor, Producers Service Corporation and Technicolor. Before long, a multitude of competing proprietary options were available to producers who wished to make films in 3-D.

The heady initial success of Natural Vision rapidly subsided. Milton Gunzburg's exclusive contract to distribute the Polaroid Corporation’s 3-D glasses to theatrical clients expired in July 1953 (Anon., 1953d) The United States Patent Office rejected Natural Vision’s patent applications, declaring the system’s basic principles as already well-known to inventors and technicians working in stereo cinematography (Gunzburg, 1953). By mid-1953, numerous companies were supplying theaters with projection equipment for 3-D presentations, leeching what had become a vital source of revenue for the Natural Vision Corporation. Mere months after its greatest commercial successes, the Natural Vision Corporation ceased operations (Anon., 1953e) .

At least eight Natural Vision camera units were built under the general supervision of O. S. Bryhn – most of these were later sold off and dismantled, with their Mitchell NC cameras being repurposed for ordinary 2-D use. At least one intact Natural Vision camera mount survives to the present day. This unit was used to film the 1960 20th Century-Fox release September Storm, which combined 3-D with 2.35:1 anamorphic projection (derived from original spherical photography). The last known use of Natural Vision came with the 1962 “nudie-cutie” feature, Adam and Six Eves.

An early Natural Vision camera rig being assembled at Richardson Camera in Burbank, CA. Note the mirrors mounted on micrometers between the two lenses. Note, also, the central viewfinder behind and between the mirrors.

Mike Ballew collection; courtesy Richardson family.

A massive 24-sheet billboard poster (from 1953) plays up audience expectations for spectacular ‘off-the-screen’ 3-D illusions in Arch Oboler’s Bwana Devil (1952). Such expectations arose from earlier, gimmick-laden 3-D shorts dating back decades – Plastigrams (1924), Audioscopiks (1935) and others. But Bwana Devil offers only a handful of such “gimmick” effects.

Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, CA, United States.

One-sheet US poster for House of Wax (1953). A two-dimensional poster sells 3-D as a barrage of off-the-screen effects. Preparations for the ad campaign were begun before principal photography had started, so the poster art bears only a superficial resemblance to anything in the completed film.

Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, CA, United States.

Actress Phyllis Kirk tries her hand at lining up the Natural Vision camera rig on the set of House of Wax (1953).

Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, CA, United States.

Selected Filmography

A low-budget jungle adventure starring Robert Stack, Barbara Britton, Nigel Bruce and two rather unmenacing lions. Despite questionable production trappings, the film was a massive commercial success in late 1952 and early 1953.

A low-budget jungle adventure starring Robert Stack, Barbara Britton, Nigel Bruce and two rather unmenacing lions. Despite questionable production trappings, the film was a massive commercial success in late 1952 and early 1953.

A handsomely mounted horror thriller starring Vincent Price and Phyllis Kirk, produced in early 1953 to capitalize on the sudden public interest in Natural Vision, and in 3-D generally. The film was a top grosser in the United States and across the globe in 1953. It also did respectable business with reissues in 1958, 1971 and 1982.

A handsomely mounted horror thriller starring Vincent Price and Phyllis Kirk, produced in early 1953 to capitalize on the sudden public interest in Natural Vision, and in 3-D generally. The film was a top grosser in the United States and across the globe in 1953. It also did respectable business with reissues in 1958, 1971 and 1982.

A Western action-adventure starring Guy Madison and Frank Lovejoy. The film makes energetic use of “off-the-screen” gimmick effects: with spears, arrows and sabers – even a spat jet of tobacco juice – launched into the audience.

A Western action-adventure starring Guy Madison and Frank Lovejoy. The film makes energetic use of “off-the-screen” gimmick effects: with spears, arrows and sabers – even a spat jet of tobacco juice – launched into the audience.

A science-fiction action film that in some ways anticipates the James Bond franchise. A government agent (Richard Egan) investigates mysterious fatal accidents plaguing a top-secret underground research facility in the Southwestern desert. Two berserk robots, Gog and Magog, wreak havoc in the third act.

A science-fiction action film that in some ways anticipates the James Bond franchise. A government agent (Richard Egan) investigates mysterious fatal accidents plaguing a top-secret underground research facility in the Southwestern desert. Two berserk robots, Gog and Magog, wreak havoc in the third act.

A Mediterranean maritime adventure starring Mark Stevens and Joanne Dru. The film aimed to revive interest in 3-D by combining it with 2.35:1 CinemaScope projection (extracted from spherically photographed original negatives, after the fashion of SuperScope 235) under a new trade name, Stereovision. The film did not perform as hoped at the box office.

A Mediterranean maritime adventure starring Mark Stevens and Joanne Dru. The film aimed to revive interest in 3-D by combining it with 2.35:1 CinemaScope projection (extracted from spherically photographed original negatives, after the fashion of SuperScope 235) under a new trade name, Stereovision. The film did not perform as hoped at the box office.

Technology

Photography

Natural Vision was designed to make stereoscopic cinematography immediately available to Hollywood studios, using largely familiar equipment and filming techniques only slightly more complex than ordinary 2-D. Two lightly modified Mitchell NC cameras were mounted on a common base in a face-to-face configuration. The cameras, precisely synchronized with shutters in exact phase, captured a left-eye view of the scene on one length of film, and a right-eye view on another

Twin mirrors on micrometer mounts diverted the optical axes of the lenses 90 degrees. This arrangement allowed for quick, precise pivoting of the mirrors to effect stereoscopic convergence (that is, the “centering” of subject matter in each eye, such that the projected images coincided perfectly and appeared spatially at the very plane of the screen). This mirror arrangement also allowed a relatively close interaxial (lens separation) of 3.5 in (88.9mm), 40 percent wider than the average human interpupillary distance of 2.5 in (63.5mm).

Some competing camera systems were designed to provide variable interaxials – that is, the separation of the camera lenses could be reduced to delimit parallax for closeups, or increased to achieve a more naturally rounded look to distant subjects photographed using long-focal-length lenses. But Natural Vision employed a strictly fixed interaxial, which was thought to guarantee complete stability in the camera platform so that the precise alignment of all optical elements could be maintained throughout the course of an average workday.

Dr. Julian Gunzburg, Milton’s brother and technical advisor, sought to spin Natural Vision’s overly wide interaxial into a virtue, claiming that: “In comparing the human eyes, with their shorter focal length optical system and smaller viewing field, with the larger viewing field and longer focal length lenses of the 35-mm cameras, a 3½-inch interaxial would be comparable to the 2½-inch interocular of the human eyes.” (Gunzburg, 1953)

Dr. Gunzburg created easy-to-read distance tables for use by camera crews, allowing them to produce stereo imagery that was easy to fuse and comfortable to view for extended periods. Lens focal length and camera-subject distance were the key variables. Dr. Gunzburg's mathematical model (or transmission system) was derived from the foundational work of Dr. Rudolf K. Luneburg of the Dartmouth Eye Institute. It was also indebted to Dr. Armin J. Hill of the Motion Picture Research Council, who acted as an apostle of sorts for the late Dr. Gunzburg’s ideas in Hollywood and who claimed, in his autobiography, to have introduced Milton Gunzburg to Baker and Worth (Hill, 1982).

Projection

The resulting negatives were reversed mirror images. Contrary to some published reports, Natural Vision release prints were not generally “flopped” using optical printing. Instead, release prints typically used an unconventional emulsion orientation, with the emulsion facing the screen in projection. (United Artists Corp., 1953). Special aperture plates in the camera ensured that the optical soundtrack would appear in its standard position along the guided edge of the film, despite the use of mirrors. According to Lothrop Worth, one camera aperture plate was notched to allow easy distinction between the left and right “eyes” during post-production and projection (Worth, 1995/96). This notch is not always present, or obvious, in release-print examples.

Like other two-strip 3-D films, Natural Vision prints were shown using synchronized projectors through light-polarizing filters onto a specular (“silver”, or aluminized) screen for viewing through matching light-polarizing glasses (Anon., 1953b). The basic technique of dual-strip projection was by no means proprietary and the Natural Vision Corporation made no claim of ownership. But the technique was unfamiliar to most projectionists and fraught with difficulties, creating challenges the corporation worked hard to overcome, as best it could.

Milton Gunzburg and his colleagues initially envisioned a limited number of special roadshow presentations of Bwana Devil, run by carefully trained personnel. The sudden, widespread clamor for 3-D movies in early 1953 compelled them to create projection techniques and corresponding equipment that could be employed in any ordinary cinema, by typical projectionists without much in the way of additional training. However, it seems that consistent results were not easily achieved (Higham, 1972; Oboler, 1956).

Theatres showing Bwana Devil, and all later dual-strip 3-D features, were expected to install a whole panoply of specialized equipment. A silver screen was essential to preserve light polarization, ensuring the proper transmission of left and right images to the eyes of spectators. While certain model soundheads could accommodate a mechanical interlock to hold the projectors in sync, a Selsyn electrical interlock was recommended for the sake of greater reliability, enhanced safety and overall greater ease of use. Special 25-in (63.5cm) magazines and 24-in (61cm) reels permitted a complete feature (along with perhaps a short and some trailers) to be shown with one intermission mid-program, to allow a single reel change in houses with only two projectors. Polarizing filters had to be placed over the port glass, cooled with special blowers to prevent depolarization due to overheating. These filters had to be cleaned often using a “Staticmaster” brush, specially designed to capture dust. The burning time of carbon trims had to be sufficient to cover a runtime equal to the amount of film on the outsized reels. The power capacity of DC generators or rectifiers had to be sufficient to run two projectors and lamphouses simultaneously without overheating. A maximum amount of light had to be put on the screen, to make up for loss of light through the projection filters and polarizers worn by the audience. In addition, the brightness of the left and right image fields onscreen had to balance precisely to ensure the easy fusion of the stereoscopic images (Motion Picture Research Council, 1953).

A survey of theatres showing dual-strip 3-D films in October 1953 (only some of which were filmed in Natural Vision) showed a very disappointing 25 per cent of all shows were afflicted by asynchronism (Jones, 1954). No definite numbers are available for shows marred by misalignment, mismatched illumination, out-of-focus images, or other known impediments to acceptable 3-D presentation.

References

Anon. (1953a). “Oboler Gets 500G Advance in UA's ‘Bwana’ Buyout”. Weekly Variety (January 14): p. 3.

Anon. (1953b). “Some Technical Details of Natural Vision”. International Projectionist, 28:1 (January): pp. 6–8.

Anon. (1953c). “World-Premiere of Altec-Paramount 4-Projector, No Intermission, 3-D Color Showing”. International Projectionist, 28:4 (April): p. 15.

Anon. (1953d). “Gunzberg [sic] Gets $2,500,000 From 3-D Specs; Polaroid May ‘Go It Alone’”. Weekly Variety (July 29): p. 3.

Anon. (1953e). “3-D Service, Renting Ended by Gunzburg”. Motion Picture Daily, 74:60 (September 24): p. 2.

Anon. (1961). “All-Time Top Grosses”. Weekly Variety (January 4): p. 49.

Gunzburg, Dr. Julian (1953). “The Story of Natural Vision”. American Cinematographer, 28:11 (November): pp. 534, 556, 616.

Higham, Charles (1972). Hollywood At Sunset. New York: Saturday Review Press: pp. 82–87.

Hill, Dr. Armin J. (1982). Seven Years in Magic Land. Provo, UT: Stevenson's Genealogical Center: p. 25.

Jones, R. Clark & William A. Shurcliff (1954). “Equipment to Measure and Control Synchronization Errors in 3-D Projection”. Journal of SMPTE, 62:2 (February): p. 135.

Motion Picture Research Council (1953). “Informational Bulletin #2: Recommendations to Projectionists for Showing Stereoscopic 3-D Motion Pictures”. (April 2, 1953): pp. 1–3.

Oboler, Arch (1956). Deposition of Arch Oboler. Brenco Pictures Corporation v. Arch Oboler. February 17, 1956. [Folder 7, Box 63], Arch Oboler Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress, Washington DC: p. 199.

Paramount Theatres (1952). Advertisement. Los Angeles Times (December 18): Part III, p. 11.

United Artists Corporation (1953). “Circular Letter #9” (January 30, 1953): p. 2.

Worth, Lothrop (1995–96). An Oral History with Lothrop Worth, interviewed by Douglas Bell, Academy Oral History Program, AMPAS (Academy Foundation, 1995-96), Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, CA: p. 677.

Zone, Ray (2002). “Behind the Scenes of Bwana Devil”. Stereo World, 29:2: p. 13.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Mike Ballew is a writer and film historian specializing in the history of stereoscopic motion pictures. He is currently working on a book, Close Enough to Touch: 3-D Comes to Hollywood, which tells the story of 3-D movies in the English-speaking world, prior to 1985. He has been employed in television post-production for 25 years.

Special thanks to the family of Lee Roy Richardson for providing the photograph of the Natural Vision camera rig under assembly, and to Louise Hilton and the entire staff of the Margaret Herrick Library, who have been unfailing in their assistance to the author.

Ballew, Mike (2024). “Natural Vision 3-Dimension”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.