A subtractive, three-color chromogenic process, developed by Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories engineers after World War II. It became the American industry standard for color negative and was widely adopted around the globe.

Film Explorer

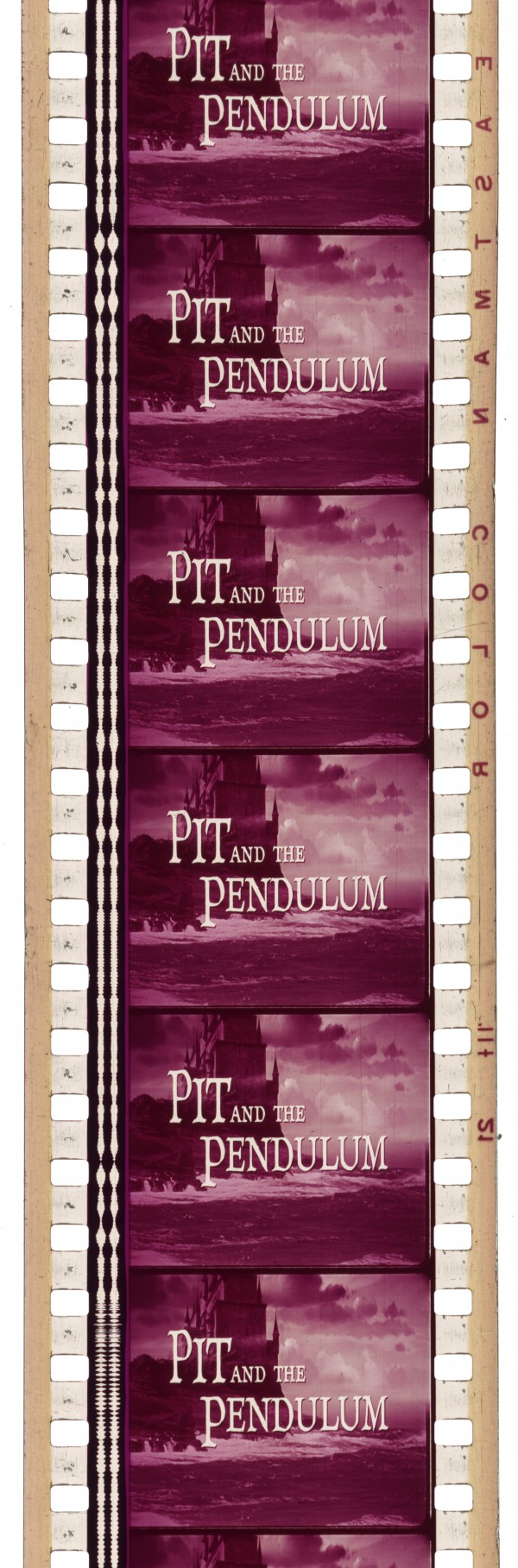

A 35mm print of The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) displaying the “Eastman Color” edge marking used by Kodak until 1963. This example illustrates the dye fading, with time, typical of Eastman Color print film from this period.

Film Atlas collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

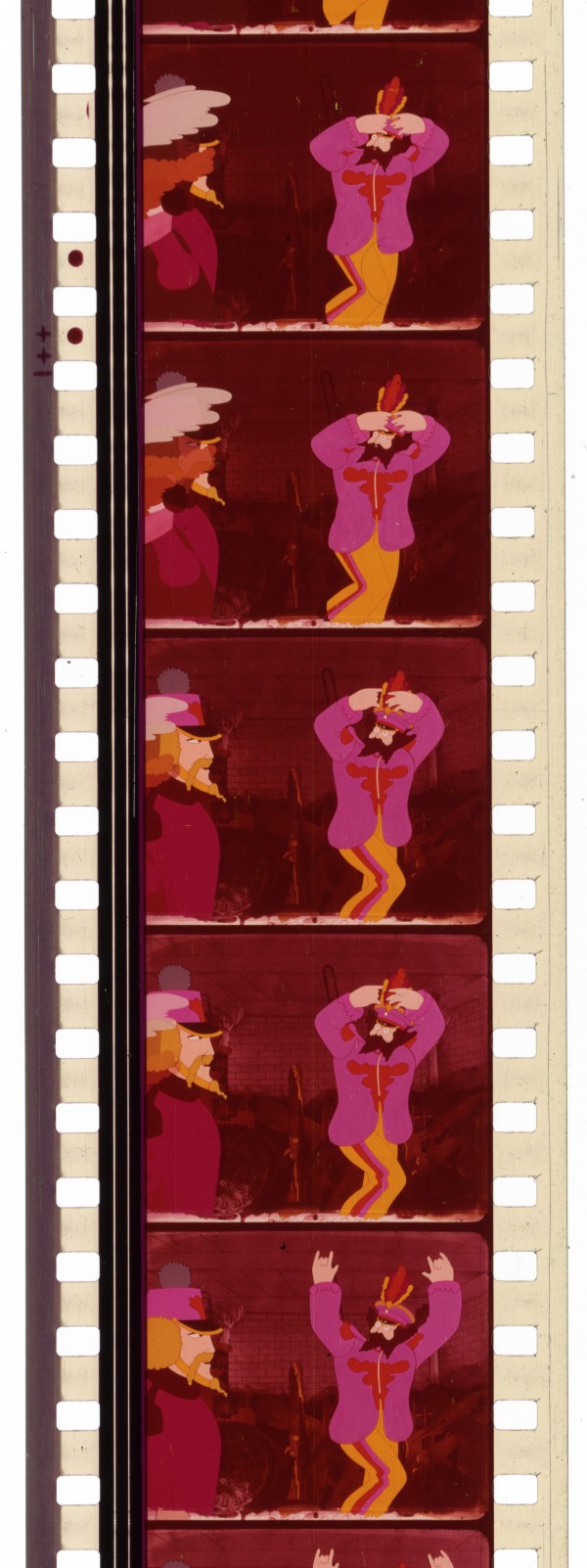

Although the cyan layer has faded, some yellow remains in this 35mm print of Yellow Submarine (1968).

Film Atlas collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

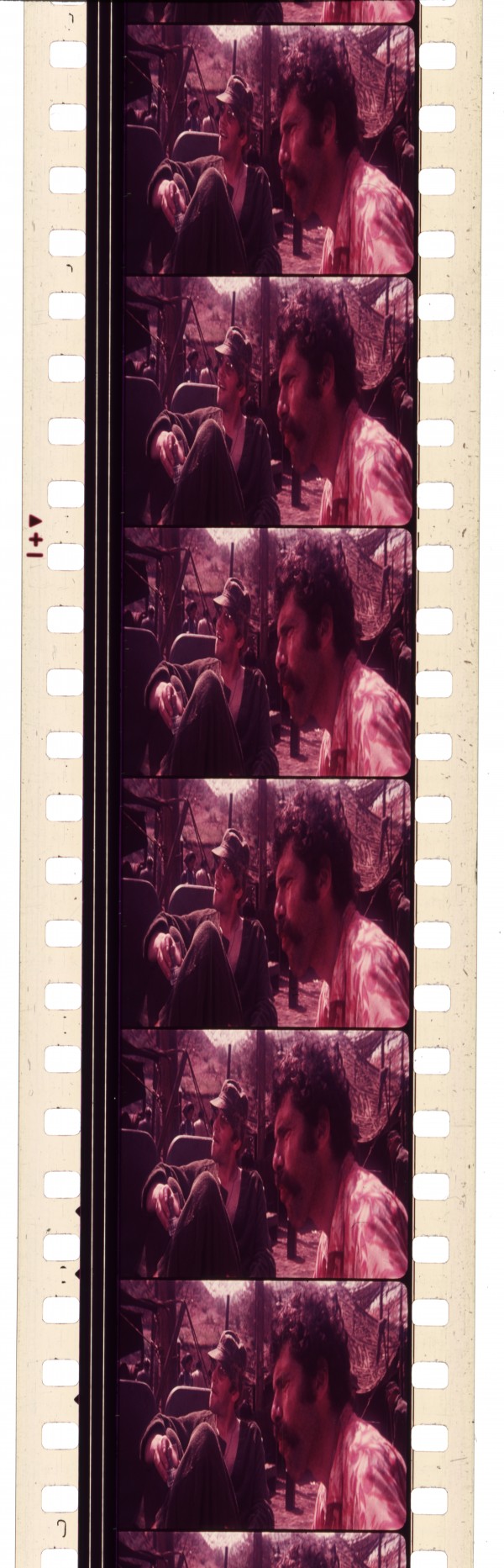

Eastman Color’s adoption period overlapped with the introduction of widescreen formats. Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould (front), in Robert Altman’s hit M*A*S*H (1970). Known for its sharp rendition, Kodak’s film stock was well-suited to anamorphic releases. Demonstrates dye fading typical of Eastman Color print film.

Film Atlas collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

The orange cast, typical of Eastman Color negative stock, evident in this 35mm camera negative of The Creation of Woman (1961), was the result of Eastman Color’s “integral mask” technology.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

N/A

Multiple aspect ratios.

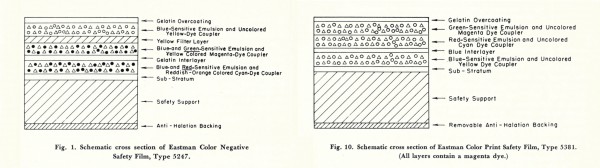

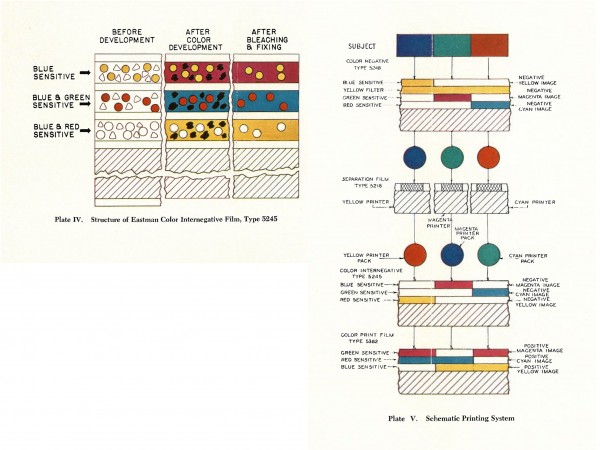

Eastman color positive film had eight layers. From top to bottom: protective gelatin overcoat; green-sensitive emulsion with magenta-dye-forming couplers; red-sensitive emulsion with cyan-dye-forming couplers; blue interlayer; blue-sensitive emulsion with yellow-dye-forming couplers; substrate; triacetate base; removable anti-halation backing. All print film couplers were uncolored. A magenta dye was dispersed throughout all three emulsion layers, which was removed during processing.

Edge markings included the standard Eastman Kodak dating and manufacturing symbols. “Color”, or “Eastman Color”, appeared on edges between 1950 and 1963.

1.

One strip typically; although for Cinerama films, three 35mm film strips were simultaneously projected one next to the other on a curved screen.

Superior color rendition to competing, contemporary chromogenic stocks (Salt. 2009: p. 268). Colors were described as natural and true-to-life by contemporary sources (DuPar, 1952). Eastman Color negative 5247, rendered blue subjects abnormally bright in reproduction, an issue that was corrected in the subsequent 5248 negative, introduced in 1952 (Hanson & Kisner, 1953). Dyes in Eastman Color film stocks of this era were unstable. Most extant materials exhibit serious dye fading.

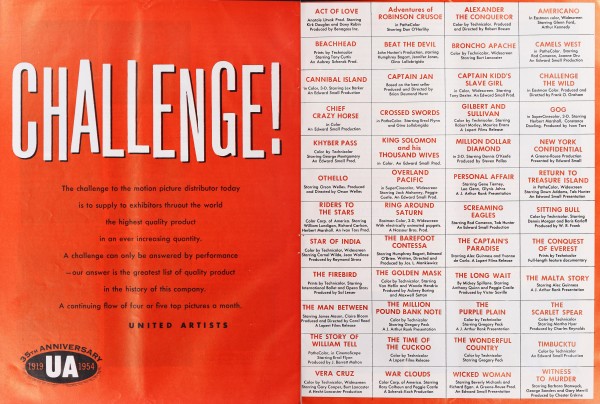

None required by Kodak. Studios and laboratories often branded Eastman Color print film as though it were an in-house color system, e.g.: WarnerColor, PathéColor, MetroColor, DeLuxe Color, ColumbiaColor. Eastman Color prints produced by Technicolor typically carried the credit, “Print by Technicolor”. Eastman Color negative could be paired with other color print stocks or systems, including Technicolor productions released with the “Color by Technicolor” credit.

Eastman Color prints used optical soundtracks (variable density, or variable area) and magnetic stripe soundtracks. The optical soundtrack was developed by edge application of a reducing agent – converting silver bromide into metallic silver – after the bleach bath. Kodak recommended a combination color-and-silver soundtrack.

Mono, 1 channel; multi-track, 4 channels (35mm prints with 4-track mag and mag/opt; and, from the mid-1970s, 35mm prints with Dolby Stereo-encoded optical soundtrack); multi-track, 6 channels (70mm).

Eastman Color negative was a multi-layer film, with three differently sensitized emulsions with incorporated color couplers. The structure of the film included nine layers. From top to bottom: protective gelatin overcoat; blue-sensitive emulsion, with uncolored yellow-dye-forming couplers; yellow filter; green-sensitive emulsion, with yellow-colored magenta-dye-forming couplers; gelatin interlayer; red-sensitive emulsion, with red-orange-colored cyan-dye-forming couplers; substrate; triacetate base; removable anti-halation backing.

Edge markings included the standard Eastman Kodak dating and manufacturing symbols. “Color”, or “Eastman Color”, appeared on edges between 1950 and 1963.

History

Eastman Color was Kodak’s first commercially viable color motion picture negative–positive film stock, with integrated color couplers. Unlike many of the color technologies that preceded it, Eastman Color was both a color system in its own right, and a modular set of film stocks that could be used in combination with other color processes. Compatible with existing cameras and projectors, because the full system of filters and dyes was embedded in the film’s emulsion, Kodak’s product could also be developed with modified B/W processing equipment. Eastman Color’s commercialization in 1950 radically expanded access to color for professional productions. The new stock rapidly became the American industry standard for color negative, and was adopted around the globe.

In Eastman Color, and related stocks, color-forming chemicals called “couplers” are dispersed in layered emulsions, each sensitive to different light primaries. Integrated-coupler film stocks were sometimes called monopack, or integral tripack, in the motion picture industry, to distinguish them from Technicolor’s three-strip solution, and interest in them dated to experiments by Rudolph Fischer in the early twentieth century (Weissberger, 1970: p. 654). An early and persistent problem, though, was that the couplers would diffuse within the emulsion – straying between layers sensitized to different light colors. As a result, image sharpness and color reproduction were both poor. Additionally, and importantly for the professional market, duplication through multiple generations proved difficult – with color quality degrading significantly between the camera original and the final print film (Heckman, 2015: pp. 46–7).

Kodak introduced chromogenic development – processing that generated color automatically, via chemical reaction – with Kodachrome, in 1935. Kodachrome films did not suffer from “wandering” couplers, because they were not manufactured with integrated color couplers; instead, dye-forming couplers were introduced during an elaborate development process that resulted in a reversal positive (Wilhelm & Brower, 1993: pp. 21–2). This elaborate development process made Kodachrome a good match for the amateur market, but a poor one for professional film production. Hollywood filmmakers required many copies, which was difficult with Kodachrome, both because making one copy was labor-intensive, and because the process of duplication through multiple generations remained unsolved.

In the following year (1936), Germany’s IG Farben introduced Agfacolor Neu, the first film stock to employ integrated couplers. Initially, like Kodachrome, Agfacolor Neu was available only as reversal positive. Integrated couplers afforded a simpler developing process – and, within a few years, Agfacolor negative and positive were also being manufactured (Wilhelm & Brower, 1993: p. 22).

Recognizing the advantages of integrated couplers, Kodak managed to solve the problem of coupler migration in the years leading into World War II (Mees, 1942). Kodak Research Laboratory (KRL) engineers suspended couplers in fatty acid droplets to “anchor” them within the correct emulsion layer. Kodak’s solution – distinct from the innovations at IG Farben (also incorporated into Agfa Color [Weissberger, 1970: p 656]) – was applied to Kodacolor Aero, an aerial still photography stock used by the American military during World War II; and to Kodacolor, a still photography stock marketed to American consumers, from 1942.

Duplication remained a problem, and KRL continued to make major investments in color film chemistry into the postwar era. In the late 1940s, at least four groups at KRL were assigned to this work: Color Process Development (led by Wesley T. Hanson); Color Process Research (led by Nicholas Groet); Color Photographic Chemical (led by Paul Vittum); and Synthetic Organic Chemical (led by Arnold Weissberger). The specific target of a marketable 35mm film for the film industry likely grew out of a program, assigned to Hanson’s group, to create a daily print film for Technicolor – but, all four groups would ultimately contribute to Eastman Color’s innovation and refinement. Perhaps the most significant breakthrough was the decision to incorporate colored couplers, a photochemical technology that would satisfactorily resolve the duplication issue – these were designed by engineers in the Color Photographic Chemical, and Synthetic Organic Chemical groups (Waner, 2000: pp. 36–52, 222–3).

Eastman Color went on sale in early 1950, with duplicating stocks following to market later that year. In a departure from many preceding color systems, Kodak offered no in-house processing, and required no branding – laboratories were responsible for the development of Eastman Color products, and were allowed to market the service as they saw fit. Because wet processing time was significantly longer than for B/W, most laboratories that installed the process opted to buy new, larger-capacity processing equipment, rather than repurpose existing equipment (Waner, 2000: pp. 83–128). DuArt, for example, the New York-based independent lab that made the release prints for Royal Journey (1951), the first feature distributed with Eastman Color release prints, installed new machines for negative, and new tanks for positive (Waner, 2000: p 89). In Hollywood, Kodak’s stock was adopted first by specialized color labs (e.g., Technicolor, Cinecolor) – who could incorporate it into pre-existing workflows – and then, more gradually, by studio-owned and independent B/W labs (Waner, 2000: pp 83–128; Variety, 1950; Variety, 1952a; Variety, 1952b; Variety, 1953a; Variety, 1953c). Eastman Color print stock was branded by studios and laboratories as their in-house color system. For example: “PatheColor”, “Print by Technicolor”, and “Color Corp. of America” designated Eastman Color positives – printed by Pathe, Technicolor and CCA (formerly Cinecolor), respectively. Eastman Color negative was used as the camera stock for the SuperCinecolor process, and for many productions released with Technicolor prints. Innovations in printing and process-control workflows and equipment continued over the course of the ensuing decade (Horton, 1952; Bartleson & Huboi, 1956; Stott, Weller & Jackson, 1956).

Eastman Color negative outcompeted Technicolor three-strip, integrated coupler alternatives like Ansco Color (briefly adopted by MGM [Variety, 1953a]), and two-color options, such as Cinecolor and Trucolor. Unlike these color processes, which were bound to a relatively small number of laboratories with specialized expertise, Eastman Color could be sold effectively anywhere. It would ultimately be adopted in virtually every country that had an established professional film industry. Unfortunately, particularly given their immediate success and wide distribution, dye fading was a recognized problem in Eastman Color stocks from the start. Panchromatic separation film, introduced in 1951, provided some protection from fading (Foster, 1953; Motion Picture Film Department, 1957: pp. 57–8; Widmayer, 1961).

In 1951, the four groups working on color film at KRL were reorganized into a single Color Photography Division, under Hanson’s leadership (Waner, 2000: p. 223). Engineers in the Division made iterative improvements and added new products to the Eastman Color line, and associated processing sequences, over time, improving the stock’s speed, sharpness, and color rendition (see tables). Major changes, to both the stocks and the process, arrived in the mid-1970s, starting with color negative. In recognition of the magnitude of the change, Kodak renumbered the line, “rebooting” with Negative Film Type 5247 II and a new ECN-2 process, in 1974. The transition, within the industry, from ECN to ECN-2, and from ECP to ECP-2, proved gradual, with Kodak continuing to sell ECN- and ECP-compatible stocks into the 1980s. Also in the 1980s – in part due to increased demand for neglected back-catalog titles, for home video content – Kodak began to address the serious dye-fading problem that affected all of the color stocks described in this entry (Waner, 2000: pp. 152–7).

[Editor’s Note: The story of Eastman Color continues in the entries on Kodak SP and Kodak LPP stocks.]

A United Artists ad in the November 21, 1953, issue of the Motion Picture Herald shows the diverse ways that Eastman Color stock was marketed. PatheColor, Print by Technicolor, and Color Corp. of America designated Eastman Color positives; printed by Pathe, Technicolor and CCA (formerly Cinecolor), respectively. Eastman Color camera negative was used for SuperCinecolor technology prints and for some productions released with Technicolor prints, including Alexander the Great (1954, referred to by a working title, Alexander the Conqueror, in this ad).

Motion Picture Herald, November 21, 1953.

The independent laboratory DuArt, based in New York City, provided color developing and printing services for Royal Journey (National Film Board of Canada, 1951), the first feature film produced using negative and positive Eastman Color stock.

DuArt collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Selected Filmography

Antonioni’s iconic first color film was shot on Eastman Color stock, while dye-transfer prints were created by Technicolor in Rome. It won the Golden Lion at the 1964 Venice Film Festival.

Antonioni’s iconic first color film was shot on Eastman Color stock, while dye-transfer prints were created by Technicolor in Rome. It won the Golden Lion at the 1964 Venice Film Festival.

The edging effect attributed to potassium dichromate bleach is visible in many scenes in Giant (Waner, 2000: p. 100).

The edging effect attributed to potassium dichromate bleach is visible in many scenes in Giant (Waner, 2000: p. 100).

The first Indian co-production with the United States, and a significant commercial success in India, Guide was publicized on posters as an “Eastmancolor” film “printed and processed in New York”; described in the American press as shot using “Pathe color cameras” (Cameron, 1965).

The first Indian co-production with the United States, and a significant commercial success in India, Guide was publicized on posters as an “Eastmancolor” film “printed and processed in New York”; described in the American press as shot using “Pathe color cameras” (Cameron, 1965).

Daiei used imported Eastman Color stock for its first ever color production. Gate of Hell won the Grand Prix at Cannes, and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Doubtless, much of the impact derived from the color mise-en-scène and from the work of cinematographer Kohei Sugiyama.

Daiei used imported Eastman Color stock for its first ever color production. Gate of Hell won the Grand Prix at Cannes, and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Doubtless, much of the impact derived from the color mise-en-scène and from the work of cinematographer Kohei Sugiyama.

A short film, commissioned by Kodak from Sara – a Chicago-based sponsored film production company – to demonstrate its new color film stock technology. The film may have used a different, more stable, cyan coupler to that which was ultimately incorporated into Eastman Color print film Type 5381 (Waner, 2000: p. 143).

A short film, commissioned by Kodak from Sara – a Chicago-based sponsored film production company – to demonstrate its new color film stock technology. The film may have used a different, more stable, cyan coupler to that which was ultimately incorporated into Eastman Color print film Type 5381 (Waner, 2000: p. 143).

Shot on Eastman Color negatives, this is Ray’s first color film, and, arguably, the first Bengali feature film ever shot in color. Ray’s deliberate use of color enhances emotional and narrative depth, and captures the unique moods of the Himalayan landscape.

Shot on Eastman Color negatives, this is Ray’s first color film, and, arguably, the first Bengali feature film ever shot in color. Ray’s deliberate use of color enhances emotional and narrative depth, and captures the unique moods of the Himalayan landscape.

Warner Bros. was the first studio to commit to installation of the Eastman Color process (Variety, 1953c), and The Lion and the Horse was the first Eastman Color feature Warners released. It was also notable as the first feature to use newly available Eastman Color Negative Type 5248, Eastman Color Print Film Type 5381; and duplicating stocks, Types 5216 and 5247.

Warner Bros. was the first studio to commit to installation of the Eastman Color process (Variety, 1953c), and The Lion and the Horse was the first Eastman Color feature Warners released. It was also notable as the first feature to use newly available Eastman Color Negative Type 5248, Eastman Color Print Film Type 5381; and duplicating stocks, Types 5216 and 5247.

Sembène initially resisted filming in color, in no small part due to concerns about Eastman Color’s technical bias in reproducing black skin tones. However, the French co-producers of the film, eager to appeal to international tastes, imposed the use of Eastman Color negative. Mandabi guided the transition to color filmmaking in post-colonial, Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1970s (Yumibe, 2024).

Sembène initially resisted filming in color, in no small part due to concerns about Eastman Color’s technical bias in reproducing black skin tones. However, the French co-producers of the film, eager to appeal to international tastes, imposed the use of Eastman Color negative. Mandabi guided the transition to color filmmaking in post-colonial, Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1970s (Yumibe, 2024).

A pinnacle of color design – filmed and released on Eastman Color. Won the Palme d'Or at the 1964 Cannes Film Festival; nominated for five Academy Awards.

A pinnacle of color design – filmed and released on Eastman Color. Won the Palme d'Or at the 1964 Cannes Film Festival; nominated for five Academy Awards.

Posters for Godard’s first color film, Une Femme est une femme (Unidex, 1961), were proudly emblazoned with “EASTMANCOLOR”. After his second color film, Le mépris/Contempt (1963), was released in Technicolor, Godard returned to Eastman Color print film for his third, Pierrot le fou.

Posters for Godard’s first color film, Une Femme est une femme (Unidex, 1961), were proudly emblazoned with “EASTMANCOLOR”. After his second color film, Le mépris/Contempt (1963), was released in Technicolor, Godard returned to Eastman Color print film for his third, Pierrot le fou.

Fox intended to release its first CinemaScope feature, shot on Eastman Color negative, on Technicolor dye-imbibition (IB) prints. When Technicolor IB proved too soft for anamorphic widescreen, though, the lab had to pivot to costlier Eastman Color print film (Variety, 1953b). Variety reported that prints for The Robe cost $830 per copy (or $250,000 total, for the approximately 300 copies in a standard run) vs $600 per copy ($180,000 total) for Technicolor IB (Variety, 1953a). Technicolor addressed the issue in time for the release of How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco / 20th Century Fox, 1953), but it may nevertheless have driven the greater adoption of Eastman Color positive (Variety, 1955).

Fox intended to release its first CinemaScope feature, shot on Eastman Color negative, on Technicolor dye-imbibition (IB) prints. When Technicolor IB proved too soft for anamorphic widescreen, though, the lab had to pivot to costlier Eastman Color print film (Variety, 1953b). Variety reported that prints for The Robe cost $830 per copy (or $250,000 total, for the approximately 300 copies in a standard run) vs $600 per copy ($180,000 total) for Technicolor IB (Variety, 1953a). Technicolor addressed the issue in time for the release of How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco / 20th Century Fox, 1953), but it may nevertheless have driven the greater adoption of Eastman Color positive (Variety, 1955).

The first commercial film to use the original negative and positive Eastman Color stocks: Type 5247 and Type 5381, respectively. Premiered, December 21, 1951. All release prints were made directly from the original camera negative.

The first commercial film to use the original negative and positive Eastman Color stocks: Type 5247 and Type 5381, respectively. Premiered, December 21, 1951. All release prints were made directly from the original camera negative.

Cries and Whispers’ famous fades to red, were printed to Eastman Color positive. Its sumptuous red interiors were filmed by cinematographer Sven Nykvist, on Eastman Color negative.

Cries and Whispers’ famous fades to red, were printed to Eastman Color positive. Its sumptuous red interiors were filmed by cinematographer Sven Nykvist, on Eastman Color negative.

Technology

Eastman Color was a set of negative–positive motion picture film stocks marketed for use on the professional market. Photochemical innovations incorporated into Eastman Color stocks increased complexity in manufacturing, but simplified photographic processing relative to preceding color systems and stocks.

In typical three-color film stocks designed for chromogenic development, three emulsion layers are coated onto a plastic base layer. Dispersed within each emulsion layer (Kodachrome excepted) are color-forming chemicals, known as dye (or color) couplers, and light-sensitive silver halides. In photographic development, developers react with exposed silver halides to form a latent image, and are oxidized in the process. In turn, those oxidized developers react with the color couplers – triggering the release of dye clouds around the exposed silver halide crystals. The silver image is removed in subsequent processing steps, leaving only the color image formed by the dye clouds.

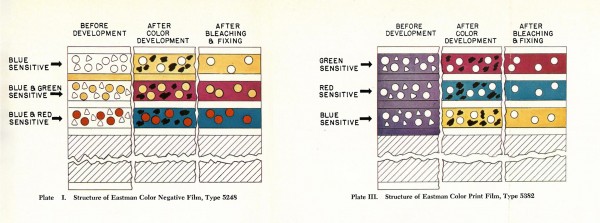

In Kodacolor negative for still photography, and then Eastman Color, color couplers were suspended in oily droplets that kept them within the correctly sensitized emulsion layer (Weissberger, 1970). Uniquely in Eastman Color negative at the time of its debut, the couplers were themselves coloured yellow and red-orange, creating an “integral mask”, which improved color rendition in subsequent generations of prints derived from the original camera negative (Hanson, 1952: pp. 224–5). Masks, traditionally applied by hand in still photography, modify part of the photographic image for a desired effect. Couplers that change from one color to another during development automatically create a color-filter mask, only in the unexposed areas of each emulsion layer. Together with an applied yellow filter layer that prevented blue-light exposure of lower emulsion layers, the colored couplers lent an orangish coloration to Eastman Color negative (Ibid.).

Eastman Color positive, or print, film was chemically simpler, with uncolored couplers (Hanson, 1952: pp. 230–1). Because screening prints were seen as more ephemeral than negatives, KRL prioritized color rendition, and cost control over stability, when selecting couplers for the positive film (Waner, 2000: p 238; Sargent, 1974: p 35). Before the late-1970s, all Eastman Color film suffered from dye fading, but the issue was particularly acute in prints.

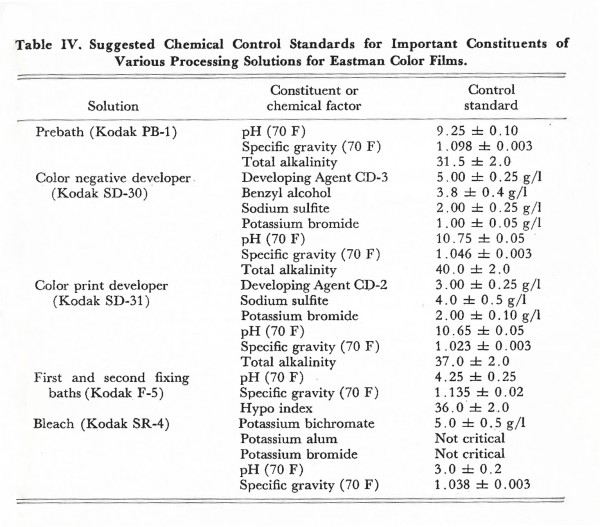

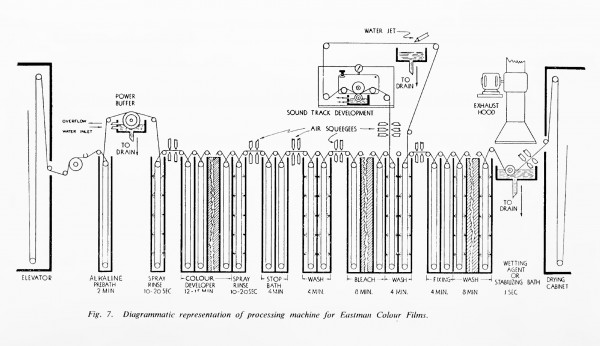

To increase sharpness, and reduce fog, in both the positive and negative stocks, Kodak applied a removable carbon backing to the reverse side of the acetate base. Deep black in color, it prevented light that reached as far as the bottom of the film strip, from reflecting back into the emulsion layers. This anti-halation layer, commonly called RemJet (for “removable” and “jet black”), was removed as a first step of film processing (W. T. Hanson, Jr. & Kisner, 1953: pp. 671, 681). Eastman Color processing involved more steps than monochrome processing; and developing time was longer. While simple for a color film stock, processing instructions for Eastman Color were complex and inflexible, relative to standard B/W. Adjustments to processing bath temperatures and duration of film immersion, which were part of the standard laboratory toolkit for controlling contrast in B/W work, were advised against and demanded consultation with Kodak staff.

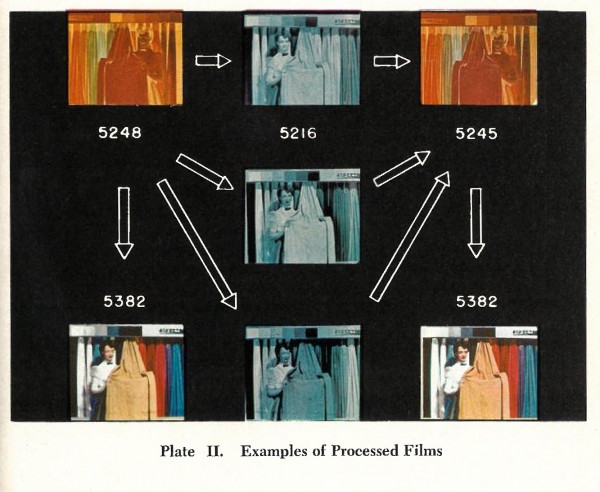

Eastman Color duplicating stocks initially comprised a color internegative and panchromatic separations (Anderson et al., 1953). Separations were a set of three B/W film strips – each a record of one emulsion layer in the color negative. Separations had several advantages: they allowed for adequate quality control in the final print film, by reducing color duplication steps (still problematic despite integral mask technology), and they were an excellent medium for long-term preservation. But they added to costs. In addition to requiring three times the length of film stock, printing from separations was prone to registration error and added significant labor to the duplicating process.

Color intermediate stock that could be used as both intermediate negative and positive was introduced in 1956, to provide an alternative to these costlier, cumbersome and more error-prone separations – a change that was especially welcome for effects and process shots (Bello et al., 1957). Then in 1968, Kodak announced Eastman Color Reversal Intermediate (CRI), which eliminated one generation from the duplication process (Beckett et al., 1968). The broadening range of Eastman Color products – Color intermediate, CRI, internegative and panchromatic separations – offered a menu of options for producers and laboratories to choose from.

Kodak’s dye options were constrained by Eastman Color’s advanced photochemistry, which both affected color rendition and contributed to the grave dye fading observed in the stock line from its debut (Wilhelm & Brower, 1993: p. 23; Sargent, 1974: pp. 35-6). Technicolor offered superior color rendition and dye stability, and it remained price competitive for release printing, long after the introduction of Eastman Color. But, on the other hand, shooting Eastman Color negative in a standard camera offered vast logistical improvements compared to filming with Technicolor’s cumbersome, and proprietary, three-strip cameras. More complex than B/W printing, Eastman Color printing was, nevertheless, much simpler than Technicolor printing. In addition, Eastman Color prints were sharper than Technicolor – a particular benefit for widescreen and small-gauge formats (Morris, 1954; Foster, 1953; Merritt, 2008).

Thanks to its colored couplers, Eastman Color provided superior color rendition when compared to its chromogenic competitors, such as Ansco Color. And it could faithfully render a much larger color space than two-color competitors, such as Cinecolor. With Ansco out of the theatrical market by the mid-1950s, and few competitors in foreign markets, Kodak easily conquered domestic and global demand for professional color motion picture stock. Only in the 1970s, in the final years of the ECN process, as Fuji Film began to penetrate the world market, would Kodak’s complete dominance be threatened.

Left: The layers of Eastman Color negative. The top, yellow-forming layer, had standard, uncolored couplers. This seems to have been due to technological, or chemical, constraints; Hanson noted that the rendering of yellows and greens would be improved if the top layer incorporated colored couplers. The yellow filter layer absorbed blue light, preventing it from exposing the green- and red-sensitive layers closer to the base (W. T. Hanson, Jr., 1952) – all photographic emulsions are sensitive to blue light. The negative’s red layer also had sensitivity in the green portion of the spectrum. Right: The layers of Eastman Color print film. The yellow image layer was placed against the base, since it contributed least towards final image sharpness. A blue interlayer, and magenta dye infused throughout all three print-film emulsion layers, reduced unwanted exposure – the magenta dye was removed during processing (Hanson, 1952; Hanson & Kisner, 1953). Because print is the final step in duplication, the positive incorporated standard, uncolored couplers.

Hanson, W. T., Jr. (1952). “Color Negative and Color Positive Film for Motion Picture Use”. Journal of the SMPTE, 58:4 (Mar.): pp. 223–38.

A cross section of Eastman Color print film, showing the magenta, cyan and yellow emulsion layers on top of the base.

Image Permanence Institute, Rochester, NY, United States.

Left: This illustration of the development process in Eastman Color negative film) models the integral mask, and demonstrates how the emulsion layers change during development and bleaching. Unwanted dye absorption, differentially affected exposure in printing, resulting in progressively poorer color rendition through successive duplication generations. Ideally, dyes would absorb only the light of their complement, but Kodak engineers had to balance this technical goal against other factors in dye selection, including chemical compatibility with the coupler reaction and stability over time. Colored couplers presented a clever solution. For example, the magenta dye in Eastman Color negative absorbed not only green light (desirable) but also blue light (undesirable). Giving the magenta couplers a yellow hue meant that blue printer light would be absorbed evenly across the layer, no matter whether it struck still-yellow couplers, which had not reacted in development, or magenta ones that had. Right: The development process in Eastman Color print film, illustrated in the same manner.

Hanson, W. T., Jr. & W. I. Kisner (1953). “Improved Color Films for Color Motion-Picture Production”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, 61:6 (December): pp. 667–701.

Chemicals used in the original iteration of the ECN process, which debuted with Type 5248. Note the inclusion of highly toxic potassium bichromate (now called potassium dichromate) in the bleaching solution – such a toxic compound could not safely be held in all processing machines designed for B/W use (Hanson, 1952). Hazards aside, potassium dichromate would later be replaced, due to concerns over its role in unwanted edge effects in high-contrast areas of the image (Waner, 2000: pp. 135–6).

Hanson, W. T., Jr. & W. I. Kisner (1953). “Improved Color Films for Color Motion-Picture Production”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, 61:6 (December): pp. 667–701.

Laboratories that had historically processed only B/W could, in principle, convert existing equipment for the Eastman Color processes – so long as their machines could safely hold potassium dichromate bleach. However, as this schematic demonstrates, Eastman Color processing involved a great number of baths – subdividing the tanks of machines designed for B/W posed multiple problems, especially as the film had to spend longer, on average, in each bath. As a result, many laboratories opted to install new equipment. Note the separate side tank for soundtrack development.

Craig, G.J. (1953). “Eastman Colour Films for Professional Motion Picture Work”. British Kinematography, 22:5 (May): pp. 146–58.

Duplication two ways – direct from camera negative (left); or via B/W panchromatic separations and color internegative(right). During this period, release prints for the domestic market were commonly made direct from the camera negative – foreign release prints were copied from intermediate materials, and, therefore, suffered from poorer image quality (Simmons, 1962). Note also the color created in the negatives by Eastman Color’s colored couplers and yellow filter layer – this immediately recognizable hue aids in quick identification of Eastman Color negative materials.

Hanson, W. T., Jr. & W. I. Kisner (1953). “Improved Color Films for Color Motion-Picture Production”. Journal of the SMPTE, 61:6 (Dec.): pp. 667–701.

Eastman Color internegative Type 5245’s "false sensitization", represented in the film’s structure (on the left), and within the duplication workflow, from color negative to print, through B/W separations and color internegative (on the right). To achieve better sharpness, Kodak engineers mismatched color forming layers and light primaries – a possibility afforded by the necessity of printing through B/W separations. Note that the red-sensitive layer in the internegative (the third step depicted in the workflow) forms the yellow (not cyan) image; the green-sensitive layer forms the cyan (not magenta) image; and the blue-sensitive layer forms the magenta (not yellow) image. Grain reduction in Type 5253 obviated the need for false sensitization, simplifying printing work, especially when intermediate and original camera negative materials were intercut (Anderson et al., 1953) – quite possibly an all-too-frequent practice.

Hanson, W. T., Jr. & W. I. Kisner (1953). “Improved Color Films for Color Motion-Picture Production”. Journal of the SMPTE, 61:6 (Dec.): pp. 667–701.

References

American Cinematographer (1950). “New Eastman Color Film Tested by Hollywood Studios and Film Labs”. American Cinematographer, 31:3 (Mar.): pp. 95 & 102.

Anderson, C. R., N. H. Groet, C. A. Horton & D. M. Zwick (1953). “An Intermediate Positive-Internegative System for Color Motion Picture Photography”. Journal of the SMPTE, 60:3 (Mar.): pp. 217–25.

Bartleson, C.J. & R.W. Huboi (1956). “Exposure Determination Methods for Color Printing: The Concept of Optimum Correction Level”. Journal of the SMPTE, 65:4 (Apr.): pp. 205–15.

Beckett, Clark, Robert A. Morris, K. Schafer & J. Marvin Seemann (1968). “Preparation of Duplicate Negatives Using Eastman Color Reversal Intermediate Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 77:10 (Oct.): pp. 1053–6.

Beeler, Raymon L., Robert A. Morris & C. Weston Simonds (1968). “A New, Higher Speed Color Negative Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 77:9 (Sep.): pp. 988–90.

Bello, H. J., Jr., N. H. Groet, W. T. Hanson Jr., C. E. Osborne & D. M. Zwick (1957). “A New Color Intermediate Positive-Intermediate Negative Film System for Color Motion-Picture Photography”. Journal of the SMPTE, 66:4 (Apr.): pp. 205–9.

Cameron, Kate (1965). “Inspirational India Film”. New York Daily News (January 31), Drama Section, p. 1.

Craig, G.J. (1953). “Eastman Colour Films for Professional Motion Picture Work”. British Kinematography, 22:5 (May): pp. 146–58.

Crowther, Bosley (1952). “New Color Deal”. The New York Times (March 9), Drama Section, p. 1.

Dundon, Merle I. & Daan M. Zwick (1959). “A High-Speed Color Negative Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 68:11 (Nov.): pp. 735–38.

DuPar, Edwin B. (1952). “WarnerColor – Newest of Color Film Process”. American Cinematographer, 33:9 (Sep.): pp. 384–5, 402–4.

Eastman Kodak Company (1942). Eastman Motion Picture Films For Professional Use (Motion Picture Film Department). Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Company. https://archive.org/details/kodak-1942-eastman-motion-picture-films-for-professional-use/page/n1/mode/2up.

Eastman Kodak Company (1957). Storage and Preservation of Motion Picture Film. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Company. https://archive.org/details/kodak-1957-storage-preservation-motion-picture-film/page/1/mode/2up.

Eastman Kodak Company (2007). Kodak Essential Reference Guide. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Company. https://archive.org/details/KodakEssentialReferenceGuide/mode/2up.

Evans, C.H. & J. F. Finkle (1951). “Sound Track on Eastman Color Print Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 57:3 (Aug.): pp. 131–9.

Evans, Ralph M., W. T. Hanson Jr. & Lyle W. Brewer (1953). Principles of Color Photography. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Foster, Frederick (1953). “Eastman Negative-Positive Color Films For Motion Pictures”. American Cinematographer, 34:7 (Jul.): pp. 322–3, 348–9.

Foster, Frederick (1959). “A Faster Color Negative”. American Cinematographer, 40:6 (Jun.): pp. 364–5, 368 & 370.

Hanson, W. T., Jr. (1952). “Color Negative and Color Positive Film for Motion Picture Use”. Journal of the SMPTE, 58:4 (Mar.): pp. 223–38.

Hanson, W. T., Jr. & W. I. Kisner (1953). “Improved Color Films for Color Motion-Picture Production”. Journal of the SMPTE, 61:6 (Dec.): pp. 667–701.

Heckman, Heather (2015). “WE’VE GOT BIGGER PROBLEMS: Preservation during Eastman Color’s Innovation and Early Diffusion”. The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists, 15: 1: pp. 44–61. https://doi.org/10.5749/movingimage.15.1.0044.

Horton, C. A. (1952). “Printer Control in Color Printing”. Journal of the SMPTE, 58:3 (Mar.): pp. 239–44.

Kisner, W. I. (1962a). “A Higher Speed Color Print Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 71:10 (Oct.): pp. 779–81.

Mees, C. E. Kenneth (1942). “Direct Processes for Making Photographic Prints in Color”. Journal of the Franklin Institute, 233:1 (Jan.): pp. 41–50.

Merritt, Russell (2008). “Crying in Color: How Hollywood Coped When Technicolor Died”. Journal of the National Film and Sound Archive (Australia), 3: 2/3: pp. 1–15.

Morris, James (1954). “1954 Seen as Biggest Year for Color”. International Projectionist, 29:1 (Jan.): pp. 7–8, 31–2.

Motion Picture Daily (1958). “Technicolor Takes Over Warner Laboratories”. Motion Picture Daily (Sept. 3): p. 2.

SMPTE (1959). “New Products (and Developments): A New 35mm Eastman Color Negative Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 68:6 (June): p. 444.

Rowan, Arthur (1950). “Capturing Realism in Color”. American Cinematographer, 31:9 (Sep.): pp. 306–7, 322–4.

Salt, Barry (2009). Film Style & Technology (3rd edn). London: Starword. http://www.starword.com/fstyleTZ.pdf.

Sargent, Ralph N. (1974). Preserving the Moving Image. Washington, DC: Corporation for Public Broadcasting & the National Endowment for the Arts. https://archive.org/details/preservingmoving00sarg/mode/2up.

Simmons, Norwood L. (1962 ). “The New Eastman Color Negative and Color Print Films”. American Cinematographer, 43:6 (Jun.): p. 362–3, 385.

Stott, John G., William R. Weller & J. Edward Jackson (1956). “Automatic Timing of Color Negatives”. Journal of the SMPTE, 65:4 (Apr.): pp. 216–21.

Stull, William (1942). “Kodacolor Introduces Negative-Positive Color Stills”. American Cinematographer, 23:3 (Mar.): pp. 118–9.

Variety (1950a). “373G Net Loss for Cinecolor”. Variety (Jan. 25) : p. 4.

Variety (1950b). “Techni Customers, Via Decree, Get Right to Cancel Future Prod. Pacts”. Variety (Mar. 1): p. 18.

Variety (1952a). “Declining Costs, Added Facilities Seen Cueing All Tinters in 3 Years”. Variety (Apr. 9): p. 7.

Variety (1952b). “N.Y. Labs Look to Color Video to Get ’Em Out of the B&W Lag”. Variety (Nov. 26): p. 7.

Variety (1953a). “Metro Seen Switching to Eastman Color on Coast; Techni Problem”. Variety (Aug. 26): p. 7.

Variety (1953b). “Print Problem Delaying ‘Robe.’”. Variety (Aug. 5): p. 4.

Variety (1953c). “WarnerColor Process Set to Replace Technicolor on Entire WB Roster”. Variety (Sep. 16): p. 4.

Variety (1955). “Techni Price Rise Consequences; Kalmus Gives Views; Eastman’s Stand”. Variety (Nov. 2): p. 25.

Waner, John (2000). Hollywood’s Conversion of All Production to Color. Newcastle, ME: Tobey Publishing.

Weissberger, Arnold (1970). “A Chemist’s View of Color Photography: How Does Color Photography Work? What Is Required of the Light-Sensitive Material? What Is the Origin of the Image Dyes?”. American Scientist, 58:6: pp. 648–60.

Widmayer, William (1961). “Cold Storage Protects Color Negatives”. American Cinematographer, 42:3 (Mar.): pp. 170–2, 174.

Wilhelm, Henry & Carol Brower (1993). The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs: Traditional and Digital Color Prints, Color Negatives, Slides, and Motion Picture. Grinnell, IA: Preservation Publishing Company.

Yumibe, Joshua (2024). “On Vivid Colors and Afrotropes in African and Diasporic Cinemas”. In Yumibe, Joshua & Sarah Street (eds), Global Film Color: The Monopack Revolution at Midcentury. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Zwick, Daan (1962). “How Color Negative Film Surface Characteristics Affect Picture Quality”. Journal of the SMPTE, 71:1 (Jan.): pp. 15–20.

Patents

Eastman Color was the result of decades of innovation and research activities. Relevant patents include:

Evans, Ralph M. & Wesley T. Hanson Jr. Neutral Gray Sound Track. US Patent 2,231,663, filed May 6, 1938, and issued February 11, 1941.

Evans, Ralph M. & Wesley T. Hanson Jr. Sensitizing in Color Photography. US Patent 2,360,214, filed March 4, 1943, and issued October 10, 1944.

Fierke, Scheuring S. Dispersing Mixtures of Resins and Coloring Materials in Gelatin. US Patent 2,272,191, filed December 26, 1940, and issued February 10, 1942.

Glass, Dudley B., Paul W. Vittum & Arnold Weissberger. 1-Hydroxy-2-Naphtamide Colored Couplers. US Patent 2,521,908, filed March 13, 1947, and issued September 12, 1950.

Glass, Dudley B., Paul W. Vittum & Arnold Weissberger. Colored Couplers. US Patent 2,453,661, filed May 3, 1944, and issued November 9, 1948.

Glass, Dudley B., Paul W. Vittum & Arnold Weissberger. Colored Couplers. US Patent 2,455,169, filed May 3, 1944, and issued November 30, 1948.

Glass, Dudley B., Paul W. Vittum & Arnold Weissberger. Colored Couplers. US Patent 2,455,170, filed May 3, 1944, and issued November 30, 1948.

Hanson, Wesley T., Jr. Color Correction. US Patent 2,294,981, filed May 25, 1940, and issued September 8, 1942.

Hanson, Wesley T., Jr. Color Correction Mask. US Patent 2,336,243, filed July 8, 1941, and issued December 7, 1943.

Hanson, Wesley T., Jr. False-color or False-sensitized Photographic Film Containing Colored Couplers. US Patent 2,763,549, filed November 3, 1951, and issued September 18, 1956.

Hanson, Wesley T., Jr. Integral Mask for Color Film. US Patent 2,499,966, filed May 3, 1944, and issued September 21, 1948.

Hanson, Wesley T., Jr. Photographic Developers Containing Acylamino Groups. US Patent 2,350,109, filed September 11, 1941, and issued May 30, 1944.

Higgins, George C. & Nicholas H. Groet. Multilayer Photographic Film Having Improved Resolving Power. US Patent 2,697,036, filed November 23, 1949, and issued December 14, 1954.

Jelley, Edwin E. & Paul W. Vittum. Color Photography. US Patent 2,322,027, filed December 26, 1940, and issued June 15, 1943.

Jelley, Edwin E. & Paul W. Vittum. Color Photography. US Patent 2,378,265, filed November 29, 1941, and issued June 12, 1945.

Jelley, Edwin E. & Paul W. Vittum. Color Photography with Azo-substituted Couplers. US Patent 2,434,272, filed May 3, 1944, and issued January 13, 1948.

Jelley, Edwin E. & Paul W. Vittum. Photographic Screening Layer. US Patent 2,350,764, filed February 5, 1943, and issued June 6, 1944.

Mannes, Leopold D. & Leopold Godowsky Jr. Color Photography. US Patent 2,304,940, filed January 19, 1940, and issued December 15, 1942.

Mannes, Leopold D. & Leopold Godowsky Jr. Multi-layer Photographic Material Containing Color Formers. US Patent 2,304,939, filed January 19, 1940, and issued December 15, 1942.

Porter, Henry D. & Arnold Weissberger. Acylated Amino Pyrazolone Couplers. US Patent 2,369,489, filed September 4, 1942, and issued February 13, 1945.

Salminen, Ilmari F., Paul W. Vittum & Arnold Weissberger. Acylaminophenol Photographic Couplers. US Patent 2,367,531, filed June 12, 1942, and issued January 16, 1945.

Schinzel, Karl. Color Development. US Patent 2,306,410, filed July 3, 1937, and issued December 29, 1942.

Vittum, Paul W. & Rebecca J. Arnold. Photographic Color Correction Using Colored Couplers. US Patent 2,428,054, filed August 30, 1945, and issued September 30, 1947.

Vittum, Paul W., Arnold Weissberger & Lot S. Wilder. Elimination Coupling with Azo-substituted Couplers. US Patent 2,435, 616, filed July 7, 1944, and issued February 10, 1948.

Vittum, Paul W. & Lot S. Wilder. Color Photography. US Patent 2,401,713, filed March 28, 1944, and issued June 4, 1946.

Weissberger, Arnold. Nondiffusing Sulphonamide Coupler for Color Photography. US Patent 2,298,443, filed August 22, 1940, and issued October 13, 1942.

Weissberger, Arnold, Charles J. Kibler & Paul W. Vittum. Color Couplers. US Patent 2,407,210, filed April 14, 1944, and issued September 3, 1946.

Weissberger, Arnold, Ilmari F. Salminen & Paul W. Vittum. 1-Naphthol-2-Carboxylic Acid Amide. US Patent 2,474,293, filed September 10, 1947, and issued June 28, 1949.

Weissberger, Arnold, Paul W. Vittum & Charles O. Edens. 1-Cyanophenyl-3-Acylamino-5-Pyrazolone Couplers for Color Photography. US Patent 2,511,231, filed March 26, 1949, and issued June 13, 1950.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Heather Heckman is Associate Dean for Information Resources and Technology at the University of South Carolina Libraries. She formerly served as Director of the Moving Image Research Collections at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. She has a PhD in Communication Arts (Film Studies) from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Daniela Currò is Director of Moving Image Research Collections at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. She formerly served as Director and Head Curator of Cineteca Nazionale, Rome, the Italian National Film Archive, and Preservation Manager at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York.

Heckman, Heather & Daniela Currò (2025). “Eastman Color”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.