A 16-lens camera and associated projector, devised by Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince. The camera, built in 1887, was used to shoot short sequences of moving images.

Film Explorer

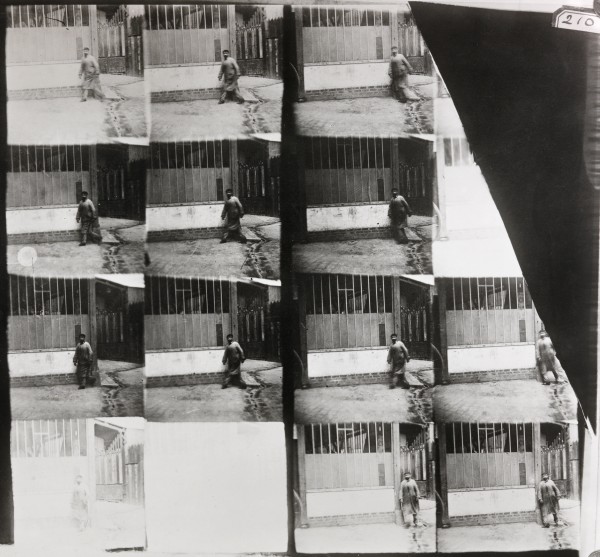

A print of the only surviving sequence, a test taken with the Le Prince 16-lens camera in August 1887, on a single glass plate. The subject, identified by Le Prince as “my mechanic”, is coming around the corner of Rue Bochart-de-Saron and Avenue Trudaine, Paris. The test was only partially successful as frames were inconsistently exposed, some were out of sequence and there were ‘flash frames’ where shutters had stuck open.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Identification

(4 in). In the proposed method of projection, frames were to be individually printed on gelatin and mounted within metallic “ribbons” on two sets of reels, replicating the way they were shot in the camera. For short, repeating cycles of movement – up to 48 frames would be printed as glass slides, for insertion into two spinning disc-shaped mounts.

Approximately 47mm x 47mm (1.875 in x 1.875 in).

B/W

Glass (camera tests); paper (Eastman Negative Paper Film, proposed but no examples known); gelatin, or glass (proposed for projection).

2

Hand-colouring envisaged.

(4 in). Two rolls of film, each four inches wide, were mounted side-by-side in the camera gate, each alternately recording sequences of eight frames, in two vertical columns of four.

Approximately 47mm x 47mm (1.875 in x 1.875 in). Nominal size – the apertures vary between 47mm and 49mm.

B/W

Frame numbers were inscribed after processing to enable the film to be cut and printed, then assembled in the correct sequence for projection.

History

Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince was born in Metz, France and studied painting in Paris, and chemistry at Leipzig University. In 1866, he became friends with John Whitley (1843–1922), who also studied at Leipzig and whose father, Joseph, an engineer, owned a successful brass foundry in the British town of Leeds, West Yorkshire. Le Prince was invited to stay at the Whitley family home, and the following year joined the firm, initially as a draughtsman. He represented Whitley Partners, and other Leeds industrialists, at the 1867 Paris Exposition. In 1869, he married Sarah Elizabeth Whitley (1844-1925), John’s sister.

Le Prince served in the French military at the 1870–71 Siege of Paris, during the Franco-Prussian War. Around two years after returning to Leeds, he and Elizabeth, a talented artist who had studied with the director of the famous Sèvres pottery, established the Leeds Technical School of Art – a valuable resource in a town where applied art had a vital role in many of its resident industries. Alongside his teaching, Le Prince also developed his interest in photography, building a studio at his home and devising techniques for applying hand-coloured photographs to ceramics. The couple were active in the cultural and artistic life of Leeds, regularly exhibiting their own and the school’s work.

In 1881, his life took a new direction: he travelled to America with John Whitley who owned a business interest in Lincrusta, an innovative embossed wallpaper product which is still produced today. “Mr. Le Prince, a Parisian artist of ability and an enterprising businessman, is to represent the manufacturers in New York,” announced the journal The Art Amateur (1882). Their venture was less successful than anticipated, and Whitley sold on his rights to an American company in 1883.

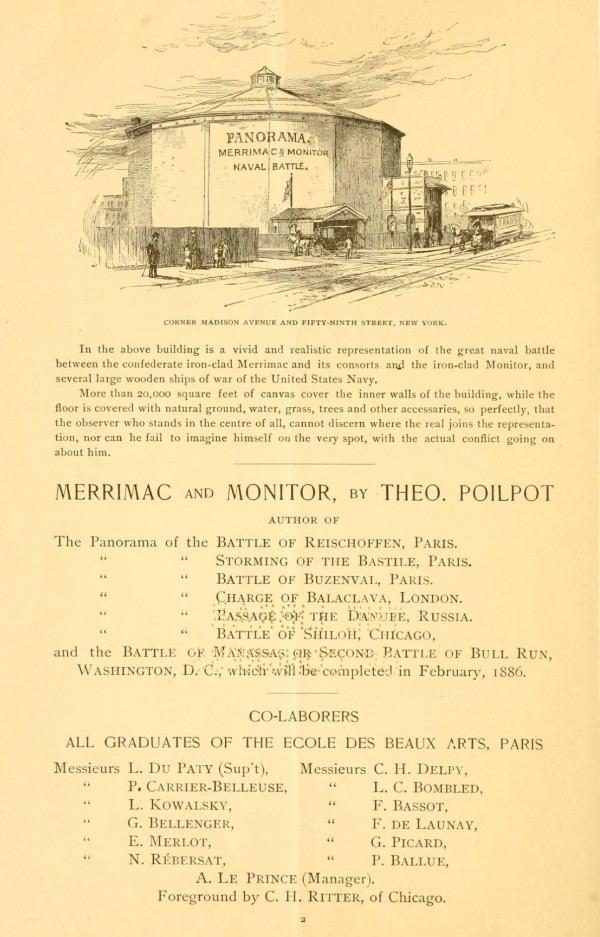

Meanwhile, Le Prince’s family had relocated to New York, and he now became involved in other ventures, notably managing a team of French artists creating cycloramas at sites in Chicago, Washington and New York. These were exhibitions of huge, dramatically lit, painted panoramas depicting historical events which – merging seamlessly with a foreground of soil, grass, water and trees – created a fully immersive viewing experience.

Around 1885, Le Prince started experimenting with ideas for creating moving pictures, building small projection devices and cameras with up to four lenses, taking picture sequences on the recently introduced Eastman Negative paper film. An alternative to glass plates, this came in rolls from 3¼ in (82.55mm) to 25 in (635mm) in width, and in lengths of up to 20 ft (6.10m). After processing, the negative was rendered translucent for printing purposes using an application of Vaseline and paraffin oil (Taylor, J. T., 1886). Paper film and its successor, stripping film, used by Le Prince in 1888, facilitated the work of early film pioneers before celluloid-based emulsions became available, in 1889.

By November 1886, Le Prince had progressed sufficiently to submit a patent proposal for a 16-lens camera (which he termed a “receiver”), and two versions of a projector (“deliverer”), illustrated with his own precise technical drawings. It was only granted by the US Patent Office in January 1888, following torturous negotiations that led to various changes (documented by Irfan Shah, 2023); Richard Howells, writing in Screen (Howells, 2006: pp. 183–6), has examined the differences between the American and British patent systems and their relevance to the commercially important issues of “precedence” and “ownership”.

Le Prince oversaw the construction of his 16-lens camera in 1887, while in Paris visiting his dying mother. He employed Hermann-Josef Mackenstein (1846–1924), a Prussian cabinet maker and mechanic who, having diversified into camera-making in 1878, had established an international reputation by the mid-1880s.

In 2000, a modern replica of this camera was constructed as part of the late Gordon Trewinnard’s The Race to Cinema project. Its website shows the camera working and modern test sequences made with it.

Le Prince returned to Leeds later that year where he carried on work that resulted in his single-lens camera of 1888, as well as various projectors, including the 16-lens one described in the patent.

Page from the programme for the Merrimac and Monitor Panorama, New York, 1886, showing the structure that housed the show and listing Le Prince as Manager. He was always known as “Augustin” or, more familiarly, “Gus”, during his lifetime.

Merrimac and Monitor Panorama Company (1886). A Comprehensive Sketch of the Merrimac and Monitor Naval Battle: Giving an Accurate Account of the Most Important Naval Engagement in The Annals of War, New York: The Merrimac and Monitor Panorama Company.

Advertisement for the Eastman Roll Holder, 1887. Designed for Eastman negative paper film, the device fitted in the plate holder slot at the rear of photographic cameras.

American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac, New York: Scovill Manufacturing Co., 1888.

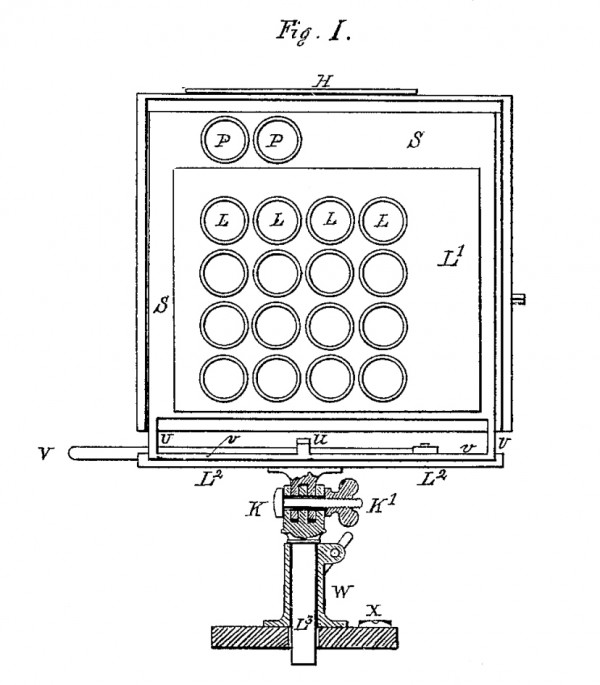

Drawing from Le Prince’s US Patent No. 376247, showing the front of the camera. There are 16 taking lenses (L), and two viewfinder lenses (P). The camera, which is about the size of standard photographic studio cameras of the period, is shown supported on a form of pan-and-tilt head.

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life. US Patent No. 376247, filed November 2, 1886, and issued January 10, 1888.

Advertisement for the photographic business of Hermann-Josef Mackenstein, 1886.

The British Journal Photographic Almanac and Photographer's Daily Companion, London: Henry Greenwood, 1886.

Selected Filmography

A test shot referenced by his son and assistant, Adolphe Le Prince in 1898/9. Not known to have survived.

A test shot referenced by his son and assistant, Adolphe Le Prince in 1898/9. Not known to have survived.

A 16-frame test, shot in Paris in August 1887, on a glass photographic plate. In a letter to his wife, Le Prince identified the man as “my mechanic” (Le Prince, 1887b). The surviving version is a copy made in 1931 by the Science Museum, London, from a vintage contact print derived from the original camera negative.

A 16-frame test, shot in Paris in August 1887, on a glass photographic plate. In a letter to his wife, Le Prince identified the man as “my mechanic” (Le Prince, 1887b). The surviving version is a copy made in 1931 by the Science Museum, London, from a vintage contact print derived from the original camera negative.

A test shot referenced by Adolphe Le Prince in 1898/9. Not known to have survived. Most likely shot in Leeds.

A test shot referenced by Adolphe Le Prince in 1898/9. Not known to have survived. Most likely shot in Leeds.

Technology

Le Prince’s patent allowed for 3–16 lenses on camera and projector, alternative methods of film drive (hand-crank, clockwork, compressed air, or electricity) and various bases for projection positives, which he proposed would be coloured by artists. He also stated, “that the details of the mechanisms forming my apparatus might be greatly varied without departing from the spirit of my invention.”

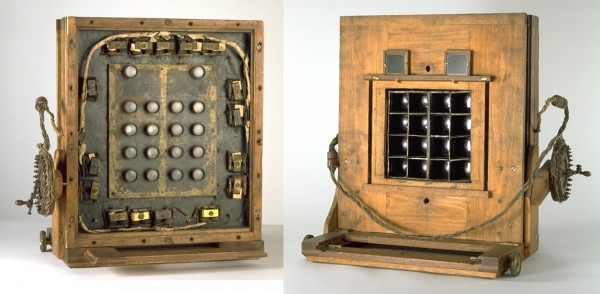

Even so, the resulting camera – now in the collection of the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford – is a surprise. With the assistance of the experienced camera-maker, Mackenstein, Le Prince had replaced his ingenious but complex hand-cranked arrangement of gears and rods, with a battery-powered system of electromagnetic relays triggering each shutter as the rotary switch was turned. Le Prince was aware that Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) had, in 1883, patented a similar method for triggering the single-shot cameras used in his motion study experiments (Muybridge, 1883), but Le Prince’s camera the shutters could be repeatedly opened and closed.

The camera’s support and, more importantly, its film magazine, are missing so we must rely on the patent to understand how it was meant to work. It was designed to take two rolls of Eastman Negative Paper Film (each 4 in [101.6mm] wide) mounted side-by-side, with the feed spools at the bottom and take-up spools at the top. Mutilated gear wheels, with teeth around half of their circumference, engaged alternately with the reels to advance the films. While one film was clamped in position behind one of two stacks of four lenses, whose shutters were triggered in sequence from top to bottom, the other film was advanced. The other film was then exposed through the second set of lenses, while the first was moved up in preparation for the next eight images. Thus images 1–8 were to be recorded on the first film; 9–16 on the second; 17–24 on the first; and so on.

The important point is that the shutter firing sequence and the film transport were designed to be synchronised through the drive shaft connected to a crank handle, or another mechanical traction method, and an integral part of the magazine. As built, the camera only has a series of relays controlling the shutters, with no provision for film advancement. To use film, the transport method connecting it to the shutters would have had to be redesigned. It may be that, because of the problems involved and the time required to solve them, the magazine was never manufactured. No examples of images recorded on film with this camera are known to exist. Le Prince used glass plates for the test sequences – he mentions this in a letter to his wife, saying they “will decide the practical possibility of my work” (Le Prince, August 27, 1887) which may have sufficed if he was already contemplating his next steps.

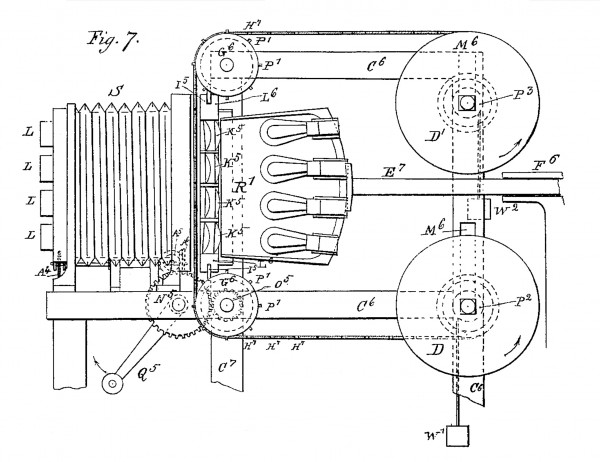

When it came to projection, Le Prince proposed that the negative frames were numbered before being cut and printed onto “flexible transparent material – such as gelatine, mica or horn” (Le Prince, 1888/9) then hand-coloured and fixed into two flexible, sprocketed metallic, or fabric, ribbons that would run side-by-side between two sets of spools in the larger of the two versions of projector he envisaged. Though designed to work in the same way as the camera, the projector’s lenses were set further apart and angled to converge at a convenient projection distance – its shutters modified to remain open longer, “to give full exposure and no interruption between successive pictures” (Le Prince,1888/9), and a set of electric light sources and condensers fitted behind the film gates. Figure 7 from the patent shows the arrangement of the spools and sprocket rollers together with the shutters, driven by a hand crank.

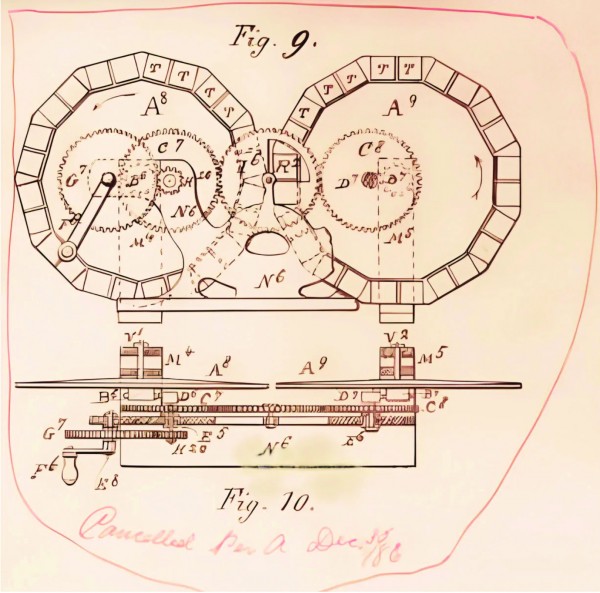

For short, repetitive movement cycles, Le Prince designed a separate “deliverer” replacing the spool arrangement and mounted between a light source and just four of the lenses. This device had a rotating shutter mechanism between two side-by-side polygonal discs, each holding up to 24 glass transparencies. As the discs rotated, the spinning shutter revealed four successive images at each turn. The illusion of movement continued for as long as the crank handle (F6) was turned. The rotating shutter idea was adopted in Le Prince’s next camera.

Both projector versions were constructed in Leeds in early 1888, and worked, according to statements made by two mechanics (Longley, 1898, 1899; Rhodes, 1898) who worked with Le Prince.

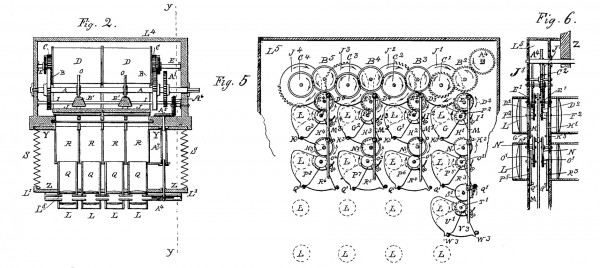

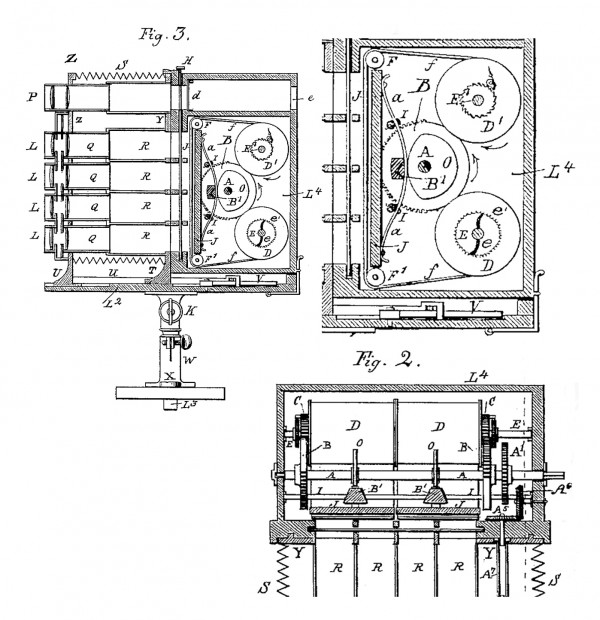

Figures from Le Prince’s 1888 US Patent. Plan view of camera and magazine (Fig. 2), showing the main shaft (A), which drives the film reels (D), operates the pressure plate (J), and, via a gear train leading to gear A4, activates the 16 shutters at the front of the camera (Fig, 5) in four vertical sequences. Cross-section of lenses and shutters (Fig. 6).

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life. US Patent No. 376247, filed November 2, 1886 and issued January 10, 1888.

Left: Front of the 16-lens camera, 1887, with cover removed, showing the 16 taking lenses, and two viewfinder lenses. By rotating the contact wheel handle (on the left side), the shutters were triggered in sequence via the relays around the edge.

Right: Camera, rear view – the knobs on the baseboard moved the front panel forwards and backwards for focusing. This, and framing, could be checked on the ground-glass viewfinder screens. A film magazine or plate holder could be fitted into the slot behind the lenses.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Top left: Figure 3 from the patent showing a side view of the 16-lens camera and magazine with, top right, an enlarged view of the magazine, showing the drive shaft (A) in cross-section, connected to half-gear wheels (B), at the side of the spools, and eccentric cams (O) that bear on and release the film pressure plate (J). Bottom right: plan view of magazine from Fig. 2, showing the counterposed half-gear wheels (B), which engage with gears (C), on the spool drums, to advance the spools alternately.

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life. US Patent No. 376247, filed 2 November 2, 1886, and issued January 10, 1888.

Figure 7 from the US patent showing a side view of the “deliverer” for projecting long sequences. The apparatus is supported by a framework (C6), and the light assembly is on a movable rod (E7). Label H7 indicates the sprocket holes in the ribbon. In the patent’s text, “D” is identified as the supply spool and “D1” the take-up spool: as in all Le Prince’s apparatus, the film moves up through the gate. However, this drawing shows the crank handle (Q5) turning in a clockwise direction which would turn the drive drum (G6) anti-clockwise, moving the belts in a downward direction which is confirmed by the arrows on spools D and D1! Label W1 indicates one of two weights keeping tension on the spools.

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life. US Patent No. 376247, filed 2 November 2, 1886, and issued January 10, 1888.

Front and plan views of the “deliverer” (projector) for short repetitive sequences, which were struck from the American patent – though text referring to them, remained. Crank handle F6 was used to rotate the two discs (A8 and A9) as well as the rotating shutter whose aperture (R2) exposed four successive frames on each turn.

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life – illustrations originally included in the application but cancelled by the US Patent Examiner. Courtesy: Irfan Shah https://louisleprince.net/

References

Art Amateur (1882). “Embossed Wall Decorations”, The Art Amateur, 6: 3 (February 1882): 65. https://archive.org/details/sim_art-amateur-art-in-the-household_1882-02_6_3/page/65/mode/1up

Aulas, Jean-Jacques & Jacques Pfend (2000). “Louis Aimé Augustin Leprince, inventeur et artiste, précurseur du cinéma”, 1895, Revue de l’Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma, 32: pp. 9–74. https://journals.openedition.org/1895/110

Fischer, Paul (2022). The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder and the Movies, New York: Simon & Schuster/London: Faber & Faber.

Howells, Richard. “Louis Le Prince: the body of evidence”, Screen, 47:2 (2006): pp. 179–200.

Le Prince, Adolphe W. (1898/9). “Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures. Notes on L A A Le Prince”. Typescript. E Kilburn Scott Collection MS165, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds.

Le Prince, Augustin (1887a). Letter to Elizabeth Le Prince (May 27). In Elizabeth Le Prince, “Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures: The Life Story of Augustin Le Prince, Inventor of Moving Pictures, with Letters and Affidavits”. Unpublished MS, Private Collection.

Le Prince, Augustin (1887b). Letter to Elizabeth Le Prince (August 18). Archive File: MS/DEP/2015/2/1. Le Prince Collection, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds. https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/439729

Le Prince, Elizabeth (1922). Letter to E Kilburn Scott. (November 1). MS165. Kilburn Scott Collection, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds.

Longley, James (1898/9). Declarations (September 19, 1898 & March 25, 1899). Transcribed in Elizabeth Le Prince, “Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures: The Life Story of Augustin Le Prince, Inventor of Moving Pictures, with Letters and Affidavits”. Unpublished MS, Private Collection.

Muybridge, E. J. (1883). Method of and Apparatus for Photographing Changing or Moving Objects. US Patent No. 279,878, filed August 31, 1881. Issued June 19, 1883.

Merrimac and Monitor Panorama Company (1886). A Comprehensive Sketch of the Merrimac and Monitor Naval Battle: Giving an Accurate Account of the Most Important Naval Engagement in The Annals of War, New York: The Merrimac and Monitor Panorama Company. https://archive.org/details/comprehensiveske00merr/page/n1/mode/2up

Manassas Panorama Co. (1886). A Comprehensive Sketch of the Battle of Manassas, or, Second Battle of Bull Run: Giving a Brief Account of One of the Most Important Engagements of the Late Civil War, Washington DC: The Manassas Panorama Company. https://archive.org/details/comprehensiveske00unse/mode/2up

Race for Cinema (2013). Website with detailed photographs of 14 working replicas of early film cameras (plus an original) from between 1886 and 1895, and examples of test clips made with them, including the Le Prince 16-lens camera (Jeff Cousins, John Adderley, Ivan Rose, Stephen Herbert and Gordon Trewinnard). http://www.theracetocinema.com/the-cutting-room/

Rawlence, Christopher (1989). The Missing Reel: Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures (ZED Productions for Channel Four and La Sept). TV documentary about the life and death of Le Prince. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8R7W6IZiRFE

Rawlence, Christopher (1990). The Missing Reel: The Untold Story of the Lost Inventor of Moving Pictures, London: HarperCollins.

Rhodes, Edgar (1898). Declaration (September 19). Transcribed in Elizabeth Le Prince, “Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures: The Life Story of Augustin Le Prince, Inventor of Moving Pictures, with Letters and Affidavits”. Unpublished MS, Private Collection.

Scott, E. Kilburn (1923). “The Pioneer Work of Le Prince in Kinematography”, The Photographic Journal, 63 (August): pp. 373–378.

Scott, E. Kilburn (1931). “Career of L A A Le Prince”, Journal of the SMPE, 17:1 (July): pp. 46–66. https://archive.org/details/journalofsociety17socirich/page/46/mode/2up

Shah, Irfan (2020). “Louis Le Prince and Leeds”, Publications of the Thoresby Society, 2nd Series: 30: pp. 1–47.

Shah, Irfan (2023). “Louis Le Prince – New Thinking: Parts 3 & 4.” The Optilogue: Studies in Popular Optical Media. https://theoptilogue.wordpress.com/2023/04/30/louis-le-prince-new-thinking-part-3/ and https://theoptilogue.wordpress.com/2023/07/10/louis-le-prince-new-thinking-part-4/

Taylor, J Traill (1886). “Film Photography”, pp. 51-61. In The British Journal Photographic Almanac and Photographer's Daily Companion, London: Henry Greenwood. https://archive.org/details/britishjournalph1886unse/page/50/mode/2up

Wilkinson, David (2015). The First Film: The Greatest Mystery in Cinema History (Guerilla Films). Feature-length documentary about the life of Le Prince.

Patents

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life. US Patent No. 376247, filed November 2, 1886 and issued January 10, 1888.

Le Prince, A. Improvements in the Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Photographic Pictures. British Patent No. 423 AD 1888, filed January 10, 1888. Addendum specifying the option of electromagnets to activate shutters and the possibility of a single lens variant filed October 10, 1888. Issued November 16, 1888.

Le Prince, A. Méthode et appareil pour la projection des tableaux animées. French Patent No. 188089, filed January 10, 1888, and issued March 23,1888.

Le Prince also patented the camera in:

Austria: Filed February 15,1888.

Belgium: Filed February 3,1888, and issued February 15,1888.

Hungary: Filed July 5,1888.

Italy: Filed March 24, 1888, and issued March 29,1889.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Following a career as a professional photographer and film, video and multivision programme maker, Michael Harvey was, until 2013, Curator of Cinematography at the National Media Museum, Bradford, UK (now the National Science and Media Museum). He was responsible for managing its world-class collection of professional and amateur cinema technology, broadening it to reflect the realities of film production with the addition of artwork, photographs, posters, documentary material and discrete collections such as that of the Hammer Films special effects make-up artists.

He curated major exhibitions including Magic Behind the Screen: 100 Years of British Cinema (1996); Bond, James Bond (2002), which toured to major venues in the USA and Canada; Myths and Visions: The Art of Ray Harryhausen (2006); Live by the Lens, Die by the Lens: Film Stars and Photographers (2008); and Drawings that Move: the Art of Joanna Quinn (2009). He also initiated a long-term series of on-stage interviews with those working in the wide range of disciplines involved in film and television production, under the banner Script to Screen.

In 2012, his work on researching and realising the first colour moving images from the original footage by Edward Raymond Turner in the Museum’s collection attracted worldwide media attention.

My thanks to former colleague Toni Booth at the National Science and Media Museum for answering various questions and accessing the original objects to check details and measurements while the Museum was closed for redevelopment. I’m also indebted to Irfan Shah for promptly responding to my queries and generously making illustrations available.

Harvey, Michael (2025). “Le Prince 16-lens process”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.