A single-lens camera, designed by Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince, that recorded a rapid succession of images on roll film which, in October 1888, was used to shoot some of the earliest moving pictures.

Film Explorer

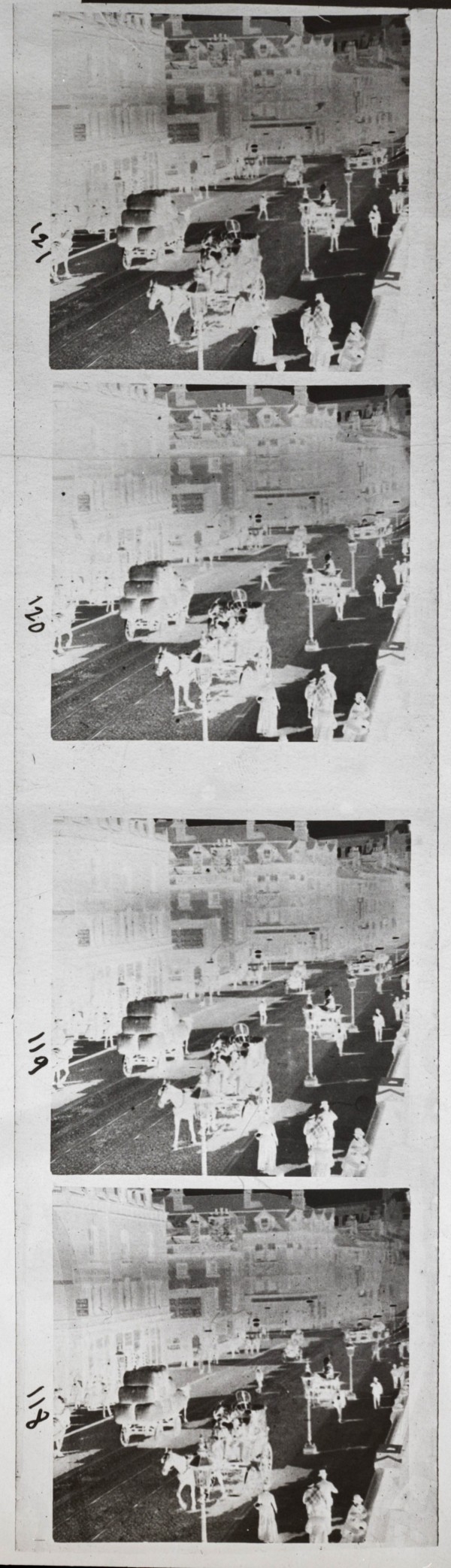

A reproduction of the negative of Le Prince’s shot of Leeds Bridge, Leeds, UK, filmed in October 1888, on stripping film. The frames were hand-numbered along the edge.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Identification

(2.375 in)

54mm x 54mm (2.125 in x 2.125 in).

B/W

Unknown

Paper, later gelatin (filming); gelatin or celluloid slides (from 1889), usually mounted in sprocketed belts, used in various prototype projectors.

Up to three.

(2.375 in)

54mm x 54mm (2.125 in x 2.125 in).

B/W

Prints of two sequences show hand-annotated frame numbers in ink, otherwise none.

History

[This entry is a continuation of Le Prince 16-lens process.]

By the late 1880s, several inventors in Europe, Britain and the United States, inspired by Eadweard Muybridge’s achievement in recording movement and reproducing it on-screen, albeit in a simplified graphical form, attempted to devise their own moving-picture devices, with varying degrees of success.

Having constructed his 16-lens camera in 1887, in Paris, and dealt with the legal matters following his mother’s death, Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince returned to Leeds. The town offered him the engineering expertise, and access to his father-in-law’s foundry, that would facilitate his planned technological developments and, he hoped, a quick return to his family in New York. Le Prince rented a workshop and engaged a joiner, Frederic Mason, and a mechanic, James Longley, in the construction of a new camera employing a single “taking lens” and just one roll of film. The paper negative and stripping negative films then available were too short for his purposes, so several films were spliced together and trimmed – in darkness, broken only by the dim glow of a red safelight – to a width of 60mm to fit the camera.

Le Prince’s camera was remarkably close in form to later film cameras. Hand-cranked, it employed a basic intermittent mechanism and a film gate with a rotating shutter behind the lens. His earliest shots were taken with this camera in the garden of the Whitley family, at Roundhay near Leeds. One, taken on October 14, 1888 – possibly the first “family movie” – shows Joseph and Sarah Whitley (Le Prince’s parents-in-law), Le Prince’s eldest son Adolphe (1872–1901), and a family friend, Annie Hartley. It can be dated precisely, as Miss Hartley mentioned the occasion in a condolence letter to Elizabeth Le Prince following Mrs. Whitley’s death on October 24, 1888. Adolphe also appears in another shot, dancing around while playing an accordion (melodeon).

Later that month, Le Prince took his camera into Leeds to film traffic passing across Leeds Bridge from an upper window of a nearby ironmonger’s premises. All earlier examples of recorded movement were of set-up subjects, so this was probably the World’s first “actuality” film. Adolphe stated that it was over 200 ft (61m) long and taken at 20 fps: a running time of around 55 seconds. (Le Prince, 1899)

The films we see today are reconstructed from copy negatives made by the Science Museum, London, in 1931, of vintage contact prints showing up to 20 frames from each of the original negatives. In 1997, this writer, along with Paul Thompson of the then National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford, collaborated with Jean-Dominique Lajoux of the Centre National de la Récherche Scientifique, Paris, to animate those fragments, creating a record of the earliest motion pictures made with a film camera. (Howells, 1997, pp. 190–1)

By coincidence, the French physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904) exhibited a roll of pictures taken with his recently constructed Chronophotographe camera at a meeting of the Académie des Sciences in Paris, on October 29, 1888. Thus, the two Frenchmen were the first to capture motion pictures in succession on a single roll of film. As an inventor, Le Prince, wary of rivals gaining knowledge of his inventions, kept his achievements secret, while Marey, a scientist, freely disclosed his.

Le Prince’s later efforts were mostly concentrated on devising ways to project his films. The transparent film bases he used to print on – such as gelatin, collodion and, latterly, Eastman Transparent Film (available in the UK from early 1890) – would readily warp, or catch fire, under the heat produced by any projecting light source. To overcome this problem, Le Prince devised a water screen, inserted between the light and the film gate. Rather than printing his films in long lengths – itself a challenge – he printed individual frames, which were then fitted between sprocketed ribbons, or into slots in the projectors he constructed.

James Longley recalled making a 16-lens projector based on Le Prince’s patent, one with a single lens and another employing three lenses, which he “considered" a perfect one, it being very simple in construction, and gave the pictures without blurs” (Longley, 1899). Le Prince also tried a variety of illumination sources with the help of electricians, one of whom, Ernest Kilburn Scott (1868–1941), went on to champion the inventor’s work, from the 1920s onwards.

By 1890, work on the 16-lens projector had reached the stage where “we had got the machine perfect for delivering the pictures on the screen” (Longley, 1898). Le Prince made plans to return, with all his equipment, to his home in New York, where he hoped to arrange for a public demonstration. Prior to leaving for America, he visited France with his bank manager friend, Richard Wilson, and his wife. Near the end of their holiday, Le Prince journeyed alone to see his brother Albert in Dijon, arranging to meet up with the Wilsons in Paris on September 16. But he never arrived, and no trace of him was ever found. Various theories about his disappearance are explored in some detail in biographies by Christopher Rawlence (1990) and Paul Fischer (2022).

Le Prince’s disappearance had long-lasting and profound effects on his family. In due course, they asked Wilson to oversee the clearance of his workshop. “Much of the apparatus was sold for what it would bring or melted as scrap,” wrote Adolphe – there were debts to be paid. Wilson reserved what he thought were “some of the important parts” for the family. Frederic Mason “picked up a few relics” and later regretted that he, “did not secure some exposed films and the drawings… That they might have historical importance was not appreciated.” (Mason, 1931; Scott, 1931: p 64)

Could the history of film have been different, had Le Prince made it back to New York? His process was still imperfect, the projection method cumbersome – hardly ready for commercial exploitation. He had recognized that the new celluloid film entering the market could be the technology to make moving pictures viable – a couple more years of work, and he could, maybe, have perfected his process.

Forty years after his death, Le Prince’s daughter Marie travelled from America to attend the unveiling, on December 12, 1930, of a memorial plaque to her father at the site of his workshop in Leeds, organized by E. Kilburn Scott. She brought over Le Prince’s cameras and other items which she deposited with the Science Museum, London. This collection is now housed at the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, just 11 miles from where Le Prince lived and worked.

Left: Le Prince’s single-lens camera, 1888, front view from right. The taking lens is at the bottom, the viewfinder lens at the top. The lever on the right adjusted focus. The cover on the right is open to reveal an inspection window, glazed with a red ‘safety’ glass. The crank handle is on the left-hand side, out of view. Right: the camera was supported by four legs that were attached to the lugs at the base of the camera. The legs were sold in the 1890s, to a Leeds commercial photographer, Charles Pickard, who donated them to the Science Museum, South Kensington, London, in 1939.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

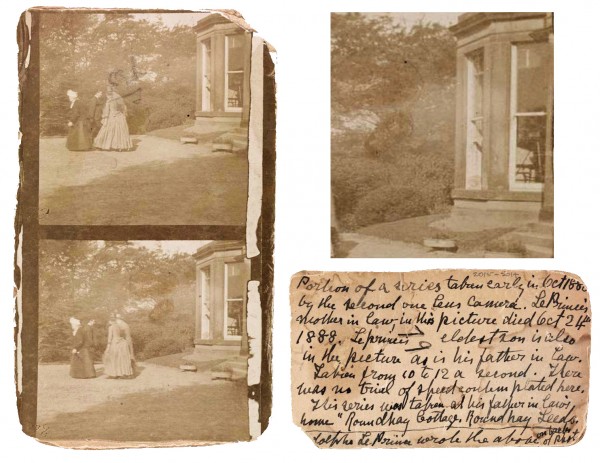

Frames from a sequence shot on paper film at Le Prince’s father-in-law’s house at Roundhay, Leeds, showing Joseph and Sarah Whitley, Adolphe Le Prince and Annie Hartley moving in circles, to keep within the camera’s field of view.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Two other frames from the Roundhay Garden Scene film (left), mounted on card, annotated on the back by Adolphe Le Prince (bottom right). It’s possible to discern another camera on a tripod, mounted in the bay window (top right). Adolphe Le Prince stated that the single-lens camera used for the sequence was the second of two made. (Scott, 1931: p. 54).

Copy of a contact print made from the original gelatin negative strips of Le Prince’s October 1888 film of traffic crossing Leeds Bridge, Leeds. This copy was made by the Science Museum, London, photographic department in 1931. Note the inconsistent spacing between frames. Le Prince numbered the frames, prior to printing slides from the negative.

Marie Le Prince (1871 –1953) alongside the single-lens camera, on top of its travelling box, holding a developing reel, at the unveiling of a memorial plaque at 160 Woodhouse Lane, Leeds (site of his workshop), December 12, 1930. The plaque is now on the premises of Leeds Beckett University Northern Film School, which stands on the site.

Courtesy Irfan Shah. Source unknown.

Selected Filmography

Test film photographed, in October 1888, at Le Prince’s in-laws’ family house in Roundhay, Leeds. Reanimated in 1997.

Test film photographed, in October 1888, at Le Prince’s in-laws’ family house in Roundhay, Leeds. Reanimated in 1997.

Test film photographed on October 14, 1888, at the Whitley family house in Roundhay, Leeds, showing Joseph and Sarah Whitley (Le Prince’s in-laws), Adolphe Le Prince (his eldest son) and a family friend, Annie Hartley. Surviving frames from this film were reanimated by the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television (Bradford) and the Centre National de la Récherche Scientifique (Paris) in 1997.

Test film photographed on October 14, 1888, at the Whitley family house in Roundhay, Leeds, showing Joseph and Sarah Whitley (Le Prince’s in-laws), Adolphe Le Prince (his eldest son) and a family friend, Annie Hartley. Surviving frames from this film were reanimated by the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television (Bradford) and the Centre National de la Récherche Scientifique (Paris) in 1997.

Test film photographed in October 1888. Reanimated in 1997.

Test film photographed in October 1888. Reanimated in 1997.

Technology

Le Prince’s original single-lens camera designs have been lost, although they are scarcely needed to understand how it works – the camera’s concept, apart from the direction of film travel, is similar to that of later film cameras. Inside, at the bottom, was a feed spool holding a roll of 60mm-wide (2.375 in) paper film or stripping film. The film passed through a gate behind the lens where it was held in place by a back plate while a rotating shutter exposed the film. As the shutter cut off incoming light, pressure on the backplate was released and the film pulled upwards to the take-up spool. Turning a crank handle, sited at the right-hand side of the camera. activated these actions through a system of gears, cams and pulleys.

Nevertheless, the film transport was rudimentary: no sprocket holes, claws, or sprocket drive. The rotation of the take-up spool pulled the film through the gate, causing frame spacing to widen, as the spool’s diameter increased with the bulk of film taken up – early frames sometimes overlapped. Le Prince’s mechanic James Longley did not consider this a problem for projection, so long as the footage was wound onto identical spools in projector and camera (Longley, 1898).

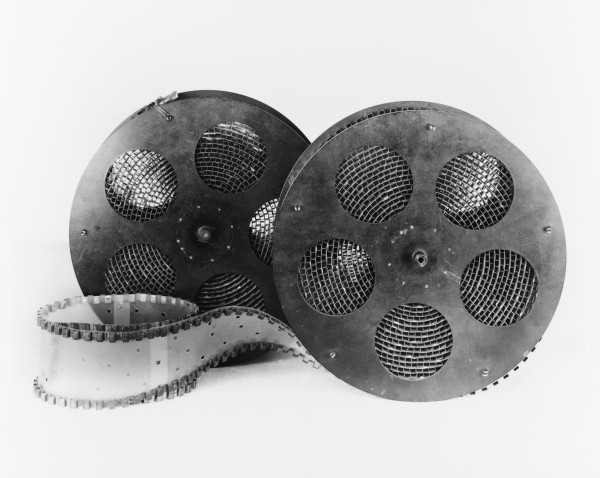

Up to this time, photographers had processed their glass plates individually in developing dishes, or in small batches using a rack in a tank. Faced with long lengths of film requiring immersion in developer for a uniform time, and subsequent drying without surfaces touching, Le Prince devised a new processing method. This employed a long roll of celluloid (cellulose nitrate had been developed during the 1870s, for non-photographic uses), studded along its edge and perforated, into which the film was rolled in a spiral. In this way, the entire length could be immersed in the processing solutions simultaneously and then, at the end of the process, dried without its surfaces touching.

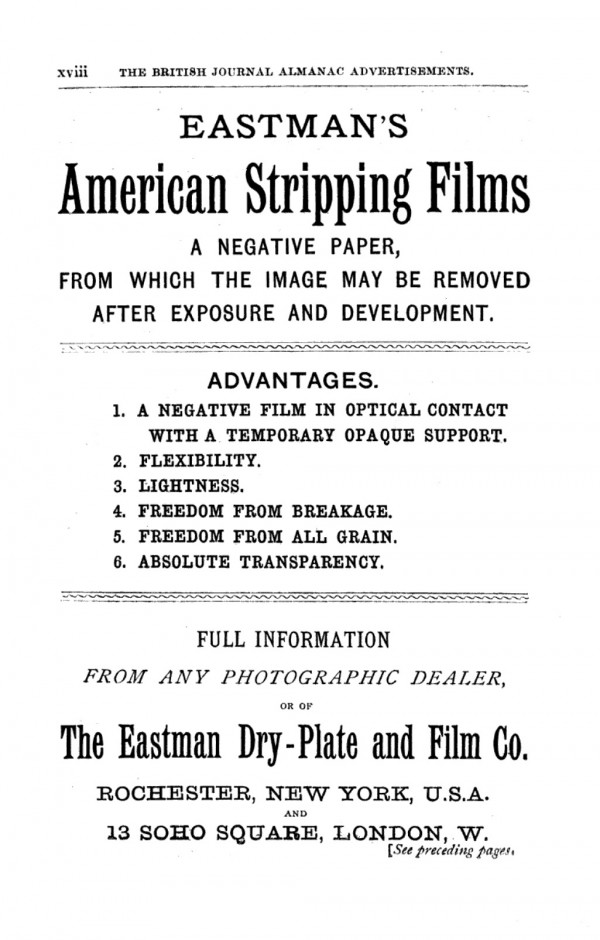

Le Prince used both paper film and stripping film (probably manufactured by the Eastman Dry-Plate and Film Company). Stripping film, available in the UK from 1887, had a gelatin–silver emulsion attached to a paper backing by a soluble gelatin layer, which was dissolved after processing, enabling the emulsion to be stripped from the backing and coated with a protective gelatin/glycerin skin, for printing. (Manfield, 1887: pp. 160–2; Anon., 1888: p. 485)

By examining the contact prints of the film strips, it is possible to determine that the Adolphe Le Prince and Leeds Bridge sequences were shot on stripping film, as the edges of transparent films diffract light and print as a white line, whilst the Roundhay Garden scene was made on paper film, where this effect is not seen.

Le Prince numbered the film frames so that transparencies made from them could be assembled in the correct order, for projection using the various “deliverers” he designed.

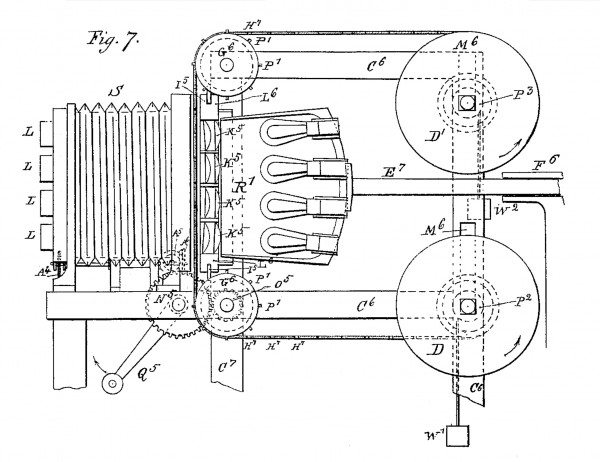

The 16-lens projector was the first to be made – in 1888. A Leeds engineer, Edgar Rhodes (Longley’s former employer) who was involved in its construction, described it thus:

“The machine consisted of four sets of gearing working alternately with a fixed amount of movement. In each of these sets of gearing was a drum having on its periphery pins…at equal intervals [which] were caused to engage with an endless band, the edges of which were perforated with holes to correspond. These endless bands were carried over guide rollers in such a manner as to form a vertical face. To each of these bands was fixed a portion of a series of Photographs of the subjects being exhibited or reproduced, these were moved by the gearing and drums at certain intervals a sufficient distance so as to cause each Photograph to be exactly central with the lenses, each band alternative with the other.

The light was supplied by a battery of sixteen limelight burners mounted on a frame and was projected on a screen by means of sixteen lenses which were focussed on the same centre.

In front of these lenses was a frame to which was fixed sixteen shutters, one in front of each lens, and was worked by four shafts, each having four cams and driven by the same shaft that drove the gearing and drums in such manner as to cover and uncover the lenses as the pictures or Photographs came opposite to them.” (Rhodes, 1898)

Rhodes witnessed the projector working “many times” and it appears to have been a fixture in the workshop, being continually refined.

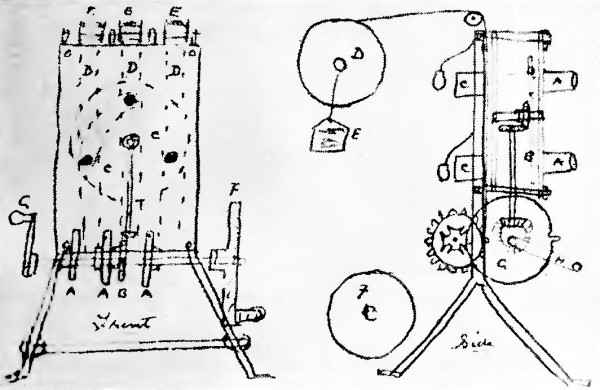

Longley went on to construct a simpler projector of Le Prince’s design with three lenses, three sprocketed “picture belts”, and a rotating shutter that opened each lens in turn. Each belt was loaded with every third frame of a sequence: belt 1 contained frames 1, 4, 7, etc.; belt 2 had frames 2, 5, 8, etc.; and belt 3, frames 3, 6, 9 etc. – they each advanced a frame, in turn, after being projected.

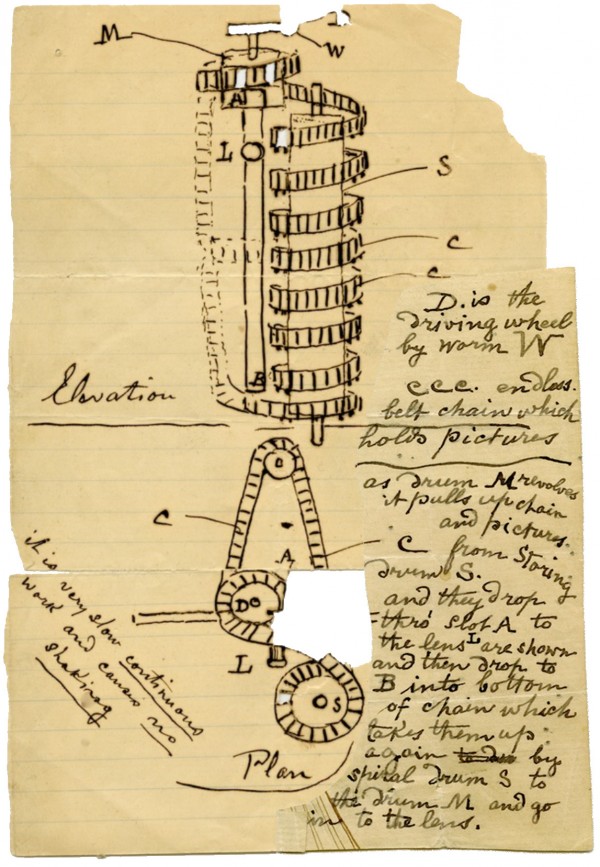

There is a sketch in Le Prince’s papers showing a single-lens projector that Longley also constructed, but neither it, nor the other projectors, have survived.

Le Prince single-lens camera, constructed in 1888. Left: interior from the rear, showing the spools of paper film and the gate. The tip of the crank handle can just be seen at the right. Right: front view, with flap open to display the aperture in the rotating shutter wheel. Photographed in 1931, at the time of acquisition by the Science Museum, London.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Le Prince’s developing spool designed to accommodate long lengths of roll film. It was constructed from 3 in x 12 in (75mm x 300mm) lengths of celluloid, glued together and edged with raised “studs” to keep the layers from touching when rolled up. The celluloid was perforated to allow for the free movement of processing solutions.

National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

Advertisement for Eastman’s American Stripping Films, 1887.

The British Journal Photographic Almanac and Photographer's Daily Companion, London: Henry Greenwood, 1887.

Figure 7 from the US patent, showing a side view of the 16-lens “deliverer”, or projector, for long sequences. It was constructed in Le Prince’s workshop in Woodhouse Lane, Leeds. The descriptions left by Rhodes and Longley, the two engineers who constructed the mechanism, indicate that it closely resembled this drawing.

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life. US Patent No. 376247, filed November 2, 1886, and issued January 10, 1888.

Sketch by James Longley, 1888, of the three-lens projector. Left: front view showing the lenses; the rotary shutter (C), reels (E, F and G) and the paths followed by the “picture belts” (D). Each belt was loaded with every third frame: belt 1 contained frames 1, 4, 7, etc.; belt 2 had frames 2, 5, 8, etc; and belt 3, frames 3, 6, 9 etc. The belts advanced a frame, in turn, after being projected. Right: side view, showing the nearest reels (D and C), with a weight (E) – on what was likely the take-up reel – to maintain tension on the ribbons. Details – such as, how the reels were supported – are omitted, but note the use of a Maltese cross on the sprocket drive.

E. Kilburn Scott (1931), “Career of L A A Le Prince”, Journal of the SMPE, 17:1 (July).

Drawing by Le Prince (composited from two fragments) of a single lens “deliverer” (projector), 1880s. This appears to be a continuous loop device for projecting short, repeating sequences. The slide belt (C), is looped around a vertical driving wheel (D) and travels to the top, where a slide drops into a slot behind the lens (L) and, once projected, drops down into the bottom of the belt which then takes it up to the lens, to repeat the process.

MS/DEP/2015/1/1 Leeds Philosophical Society Le Prince Collection, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom. https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/439724

References

Anon.(1888). “Improved Method of Stripping Films”. In The British Journal Photographic Almanac and Photographer's Daily Companion, p.485. London: Henry Greenwood. https://archive.org/details/britishjournalph1888unse/page/485/mode/1up

Aulas, Jean-Jacques and Jacques Pfend (2000). “Louis Aimé Augustin Leprince, inventeur et artiste, précurseur du cinéma”. 1895, Revue de l’Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma, 32: pp. 9–74. https://journals.openedition.org/1895/110

Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company (1886). Illustrated Catalogue and Price List. Rochester, NY: pp. 11–12. https://archive.org/details/illustratedcatal00eastuoft/page/11/mode/1up

Fischer, Paul (2022). The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Howells, Richard (2006). “Louis Le Prince: the body of evidence”. Screen, 47:2 (Summer): pp. 179–200.

Le Prince, Adolphe W. (c.1899). “Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures. Notes on L A A Le Prince”. Unpublished typescript. E. Kilburn Scott Collection MS165, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds.

Longley, James W. (1898). Letter to Adolphe Le Prince (December 13). E. Kilburn Scott Collection MS165, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds.

Longley, James W. (1898/9), “Declarations” (September 19, 1898 & March 25, 1899). Transcribed in Elizabeth Le Prince, “Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures: The Life Story of Augustin Le Prince, Inventor of Moving Pictures, with Letters and Affidavits”. Unpublished MS, Private Collection.

Longley, James W. (1899a). Letter to Adolphe Le Prince (January 15). MS/DEP/2015/2/11, Leeds Philosophical Society Le Prince Collection, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds. https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/439746

Longley, James W. (1899b). “Declaration” (March 25). E. Kilburn Scott Collection MS165, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds.

Manfield, H. (1887). “Stripping Films”. In The British Journal Photographic Almanac and Photographer's Daily Companion, pp. 160–2. London : Henry Greenwood. https://archive.org/details/britishjournalph1887unse/page/n171/mode/2up

Mason, Frederic (1931). “Declaration Regarding Pioneer Work in Moving Pictures Done By Louis Augustin Aime Le Prince at 160 Woodhouse Lane, Leeds, England During The Years 1887 to 1890” (April 2). MS 165 E. Kilburn Scott Collection, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds.

Mason, William Jr. (1898). “Declaration” (September 19). Transcribed in Elizabeth Le Prince, ”Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures: The Life Story of Augustin Le Prince, Inventor of Moving Pictures, with Letters and Affidavits”. Unpublished MS, Private Collection.

Race to Cinema (2013). Website with detailed photographs of 14 working replicas of early film cameras (plus an original) from between 1886 and 1895, and examples of test clips made with them, including the Le Prince Single-lens camera (Jeff Cousins, John Adderley, Ivan Rose, Stephen Herbert and Gordon Trewinnard). http://www.theracetocinema.com/cameras/

Rawlence, Christopher (1989). The Missing Reel : Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures (ZED Productions for Channel Four and La Sept). TV documentary about the life and death of Le Prince. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8R7W6IZiRFE

Rawlence, Christopher (1990). The Missing Reel: The Untold Story of the Lost Inventor of Moving Pictures, London: HarperCollins.

Rhodes, Edgar (1898). “Declaration” (September 19). Transcribed in Elizabeth Le Prince, ”Missing Chapters in the History of Moving Pictures: The Life Story of Augustin Le Prince, Inventor of Moving Pictures, with Letters and Affidavits”. Unpublished MS, Private Collection.

Scott, E. Kilburn (1923). “The Pioneer Work of Le Prince in Kinematography”. The Photographic Journal, 63 (August): pp. 373–378.

Scott, E. Kilburn (1931). “Career of L A A Le Prince”, Journal of the SMPE, 17:1 (July): pp. 46–66. https://archive.org/details/journalofsociety17socirich/page/46/mode/2up

Shah, Irfan (2020). “Louis Le Prince and Leeds”. Publications of the Thoresby Society (2nd Series): 30: pp. 1–47.

Shah, Irfan (2023). “Louis Le Prince – New Thinking” (Parts 3 & 4). The Optilogue: Studies in Popular Optical Media. https://theoptilogue.wordpress.com/2023/04/30/louis-le-prince-new-thinking-part-3/ and https://theoptilogue.wordpress.com/2023/07/10/louis-le-prince-new-thinking-part-4/

Taylor, J Traill (1886). “Film Photography”. In The British Journal Photographic Almanac and Photographer's Daily Companion, pp. 51–61. London: Henry Greenwood.

https://archive.org/details/britishjournalph1886unse/page/51/mode/1up

Wilkinson, David (2015). The First Film: The Greatest Mystery in Cinema History (Guerilla Films). Feature-length documentary about the life of Le Prince.

Patents

Le Prince, A. Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life. US Patent No. 376247, filed November 2, 1886, and issued January 10, 1888.

Le Prince, A. Improvements in the Method of and Apparatus for Producing Animated Photographic Pictures. British Patent No. 423 AD 1888, filed 10 January 1888. Addendum specifying the option of electromagnets to activate shutters and the possibility of a single lens variant, filed 10 October 1888, and issued November 16, 1888.

Le Prince, A. Méthode et appareil pour la projection des tableaux animées. French Patent No. 188089, filed January 10, 1888, and issued March 23, 1888.

Le Prince also patented the camera in:

Austria: Application filed 15 February 1888.

Belgium: Application filed 3 February 1888. Approved 15 February 1888.

Hungary: Application filed 5 July 1888.

Italy: Application filed 24 March 1888. Approved 29 March 1889.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Following a career as a professional photographer and film, video and multivision programme maker, Michael Harvey was, until 2013, Curator of Cinematography at the National Media Museum, Bradford, UK (now the National Science and Media Museum). He was responsible for managing its world-class collection of professional and amateur cinema technology, broadening it to reflect the realities of film production with the addition of artwork, photographs, posters, documentary material and discrete collections such as that of the Hammer Films special effects make-up artists.

He curated major exhibitions including Magic Behind the Screen: 100 Years of British Cinema (1996); Bond, James Bond (2002), which toured to major venues in the USA and Canada; Myths and Visions: The Art of Ray Harryhausen (2006); Live by the Lens, Die by the Lens: Film Stars and Photographers (2008); and Drawings that Move: the Art of Joanna Quinn (2009). He also initiated a long-term series of on-stage interviews with those working in the wide range of disciplines involved in film and television production, under the banner Script to Screen.

In 2012, his work on researching and realising the first colour moving images from the original footage by Edward Raymond Turner in the Museum’s collection attracted worldwide media attention.

My thanks to former colleague Toni Booth at the National Science and Media Museum for answering various questions and accessing the original objects to check details and measurements while the Museum was closed for redevelopment. I’m also indebted to Irfan Shah for promptly responding to my queries and generously making illustrations available.

Harvey, Michael (2025). “Le Prince single-lens process”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.