A 35mm film format, with custom perforations, that debuted in France in 1896. Invented by Ambroise-François Parnaland.

Film Explorer

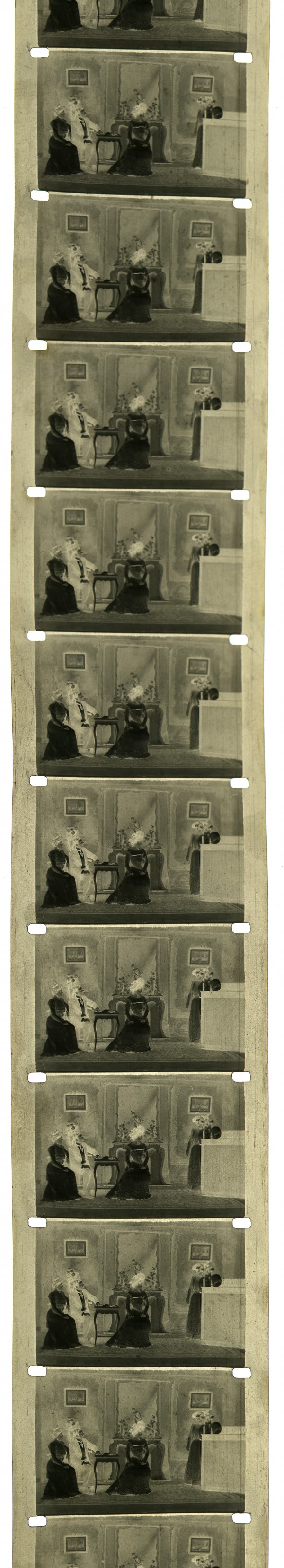

L’Enfant prodigue (1900). The 35mm Parnaland format employed three different perforation arrangements. In this example, there is a single, wide central perforation between each frame.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

This 35mm Parnaland print (of an unidentified film) features three perforations: one at each edge of the frame, plus a slightly wider, centrally placed one.

Ma Cousine (1900). This 35mm Parnaland negative features two perforations between each frame – one at the left edge, one at the right.

Identification

Unknown

Approx.

B/W, orthochromatic.

None

1B/W, orthochromatic.

All prints were B/W; some prints were hand colored.

Some Paranland prints were used for Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre presentations, in 1900, synchronized to wax-cylinder recordings.

Approximately 28.81mm x 19.42mm (1.134 in x 0.764 in).

B/W, orthochromatic.

None

History

Inventor and cinema pioneer Ambroise-François Parnaland (1854–1913) founded the Parnaland Frères company in April 1895. He filed his first patent, on February 25, 1896, for a cinematographic device using non-perforated 35mm film: the “Photothéagraphe”. On March 5, 1896, he filed another patent for the “Kinébléposcope” viewer – a variant of Georges Demenÿ’s Phonoscope. The reversible 35mm camera/projector, with perforated film, described in Parnaland’s patent of May 6, 1896, is of greater interest due to some novel innovations: an escapement movement drives a 35mm film strip, by means of an eyelet-reinforced perforation, centered between each frame, and “embossings” at left and right edges (two per frame). These embossings are driven by two mechanical feeders. No extant samples of this film have yet been unearthed.

A new patent, registered on June 9, 1896 (with several successive additions), enabled Parnaland to offer a high-performance camera, with an original mechanism, using film with several types of perforation, driven by spring-loaded “blades” – this new advancement mechanism, unique to the Parnaland’s system, was far gentler on the film stock than either the Edison or Lumière systems.

In June 1898, Doctor Eugène-Louis Doyen asked Parnaland, among others, to record some of his groundbreaking surgical procedures. Six different operations were subsequently filmed by Parnaland (using his own camera) and Clément-Maurice [Gratioulet] (1853 –1933) (with a Lumière Cinématographe). Doyen’s archive contains two negatives: one with round Lumière perforations; the other with two lateral rectangular Parnaland perforations. Parnaland, assuming he owned films made with his camera, decided to sell some of the Doyen footage in Edison 35mm format to the distributors Pathé, Radiguet and Massiot, and Georges Mendel. Films of Dr Doyen’s operations were subsequently exhibited by fairground stallholders, which caused a scandal in medical circles. The surgeon filed a complaint against Parnaland, who was ordered to pay compensation to Doyen. After these events, the two men broke off their collaboration. Yet, a 35mm camera, specially built by Parnaland for Doyen, along with the sole-surviving example of an amateur 17.5mm film camera model, survive to the present day in the preserve of Dr Doyen’s family. Curiously, Doyen registered a patent for this 17.5mm camera on January 29, 1900, even though it was clearly based on the Parnaland system.

Despite these legal headwinds, the Parnaland company continued, and succeeded in selling its machines to various distributors – the hybrid nature of the system (a variety of perforation types) was appreciated in the trade. Radiguet and Massiot announced that Parnaland projectors came with spring-loaded blades: “[allowing] two strips of different width, Lumière or Edison, to be run through, one after the other, without any modification to the device … [B]y simply adjusting the length of the connecting rod, we can accommodate special widths for strips that we would be well advised to keep for ourselves”.

Parnaland also took part in the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre project with Clément-Maurice. This dual-purpose camera, also used for Doctor Doyen’s operations, filmed L’Enfant prodigue (1900), with Félicia Mallet, and Ma Cousine (1900), with Gabrielle Rejane, with lateral perforations, and others with central perforations.

In 1897, Parnaland started to film productions of his own, specifically targeting fairground audiences. In 1904, he partnered with photographer Emmanuel Ventujol, a former operator with the Lumière brothers, to continue producing films – film catalogs were published. In 1907, having abandoned the Parnaland format, Ambroise-François Parnaland co-founded the new company Eclair, alongside Charles Jourjon. But after a few months, Parnaland was dismissed and withdrew from Eclair. In 1910, Parnaland returned to manufacturing cinematographic equipment, but, by this time, his patents had become outdated and commercial success did not follow.

Selected Filmography

Parnaland #366. Approximately 18m (59.1 ft) in length.

Parnaland #366. Approximately 18m (59.1 ft) in length.

Parnaland #60. Approximately 20m (65.6 ft) in length.

Parnaland #60. Approximately 20m (65.6 ft) in length.

Parnaland #24. Approximately 14m (45.9 ft) in length.

Parnaland #24. Approximately 14m (45.9 ft) in length.

Parnaland #208. Approximately 17m (55.8 ft) in length.

Parnaland #208. Approximately 17m (55.8 ft) in length.

Parnaland #353. Different sources list this at approximately 19m, or 25m (62.3/82.0 ft) in length.

Parnaland #353. Different sources list this at approximately 19m, or 25m (62.3/82.0 ft) in length.

Parnaland # 37. Approximately 17m (55.8 ft) in length.

Parnaland # 37. Approximately 17m (55.8 ft) in length.

Parnaland #399. Different sources list this at approximately 23m, or 35m (75.5/114.8 ft) in length.

Parnaland #399. Different sources list this at approximately 23m, or 35m (75.5/114.8 ft) in length.

Parnaland #211.

Parnaland #211.

Technology

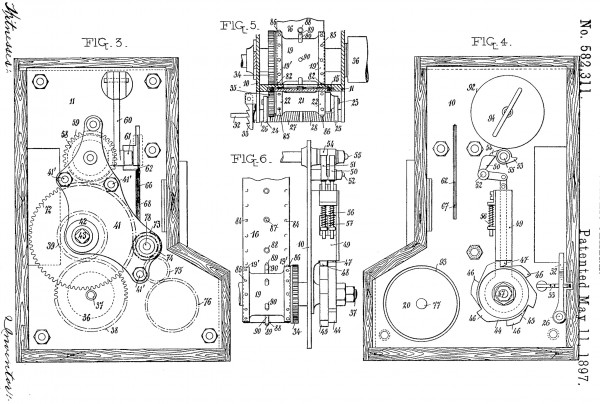

Parnaland asserted his originality on the basis of his patent filed on June 9, 1896, along with several successive additions. The 54-page patent included four additions – respectively dated August 6, 1896; November 7, 1896; March 6, 1897; and February 28, 1899. The innovative aspect of this reversible camera and projector was its drive mechanism: spring-loaded blades penetrated each central perforation in the film, pulling the film downwards and going out again, thanks to a system of two connecting rods articulated on a crankshaft.

In the November 7, 1896, addition, the spring-loaded blades could drive the film strip by means of double lateral perforations (at left and right frame edges), like the Lumière system – but, instead of Lumière’s round perforations, the Parnaland perforations were rectangular, as with Edison. In the final addition on February 28, 1899, two sets of spring-loaded blades were installed in the camera: one to drive centrally perforated film, the other set for operating with laterally (edge) perforated film. This 1899 version was manufactured and sold in a variety of forms – sometimes under the name “Cinépar”.

The surviving Parnaland films are all 35mm, but display the three different perforation types: a single wide rectangular perforation centered between each frame; three rectangular perforations between each frame, the central one being wider; and, two rectangular side perforations between each frame.

The 35mm Parnaland Cinepar camera and projector, introduced in 1899.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

Patent diagram, showing the novel spring-driven advancement mechanism. Springs [56] held and released two vertical rods [47] that caused the intermittent movement of a ratchet-gear [46], which then advanced the film.

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Kinetographic camera. US Patent 582,311, filed May 25, 1896, and issued May 11, 1897. https://patents.google.com/patent/US582311A/

References

Cinépar-Paris (1902). Le Cinépar, appareil perfectionné bté SGDG en France et à l’Étranger, Photographie animée, Liste des sujets (catalogue of films produced by Parnaland, 20pp). Paris: Edmond Lyon.

Groupe de Recherche sur l'Image dans le Monde Hispanique (GRIMH)(n.d.). Les origines du cinéma (1896–1906), “Parnaland catalogue”. https://grimh.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&layout=edit&id=7427&Itemid=717 (accessed December 10, 2024).

Mannoni, Laurent (1993). “Ambroise-François Parnaland, cinema-pioneer, co-founder of the Eclair Company”. Griffithiana, 16:47 (May): p. 10–30.

Patents

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Nouvel appareil photographique pouvant également être employé comme appareil chronophotographique dit Photothéagraphe. French Patent 254,249, filed February 25, 1896.

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Appareil de reproduction de scènes animées d’après des vues enregistrées chronophotographiquement dit le Kinébléposcope. French Patent 254,540, filed March 5, 1896.

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Appareil pour la reproduction chronophotographique de la projection de scènes animées. French Patent 256,140, filed May 6, 1896.

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Improvements in or relating to apparatus for use in receiving and projecting photographic images. British Patent 10,006, filed May 11, 1896.

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Kinetographic camera. US Patent 582,311, filed May 25, 1896, and issued May 11, 1897. https://patents.google.com/patent/US582311A/

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Appareil pour la reproduction chronophotographique et la projection de scènes animées. French Patent 257,089, filed June 9, 1896.

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Improvements in or relating to apparatus for use in receiving and projecting photographic images. British Patent 13,642, filed June 20, 1896.

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Kinetographic camera. US Patent 610,560, filed July 6, 1896, and issued September 13, 1898. https://patents.google.com/patent/US610560A

Parnaland, Ambroise-François. Improvements in or relating to apparatus for photographing and reproducing objects in motion. British Patent 6202, filed March 9, 1897.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Laurent Mannoni is Scientific Director of Heritage and Director of the Conservatoire des Techniques at the Cinémathèque Française, Paris. Author of a doctoral thesis on motion recording in the 19th century, he has published some 20 works, including: Le Grand art de la lumière et de l'ombre (1994), Etienne-Jules Marey, la mémoire de l'œil (1999), Lettres d'Etienne-Jules Marey à Georges Demenÿ (with Thierry Lefebvre and Jacques Malthête (2000), Mouvements de l'air, Etienne-Jules Marey photographe des fluides (with Georges Didi-Huberman (2004), Histoire de la Cinémathèque française (2006), L'œuvre de Georges Méliès (with Jacques Malthête) (2008), Lanterne magique et film peint (with Donata Pesenti Campagnoni) (2009), Tournages, Paris - Berlin - Hollywood, 1910-1939 (with Isabelle Champion) (2010), Alice Guy, Léon Gaumont et les débuts du film sonore (with Maurice Gianati) (2012), Les Enfants du Paradis (with Stéphanie Salmon) (2012), Georges Méliès, la magia del cine (2013), La Machine cinéma (2016), Méliès, La magie du cinéma (2020), Objectif mer, l'océan filmé (2023). He has produced around fifteen exhibitions on these subjects.

Mannoni, Laurent (2024). “Parnaland”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.

Margaux Chalançon