Although other systems had produced very brief sequences of animated photographs, Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope was the first publicly exhibited process that employed 35mm celluloid film advanced by edge-located sprocket holes. As such, the individually viewed peepshow device served as a major inspiration for projected film.

Film Explorer

A 35mm hand-colored print of A Bar Room Scene (1895). Kinetoscope prints have black edges and Edison-type perforations.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

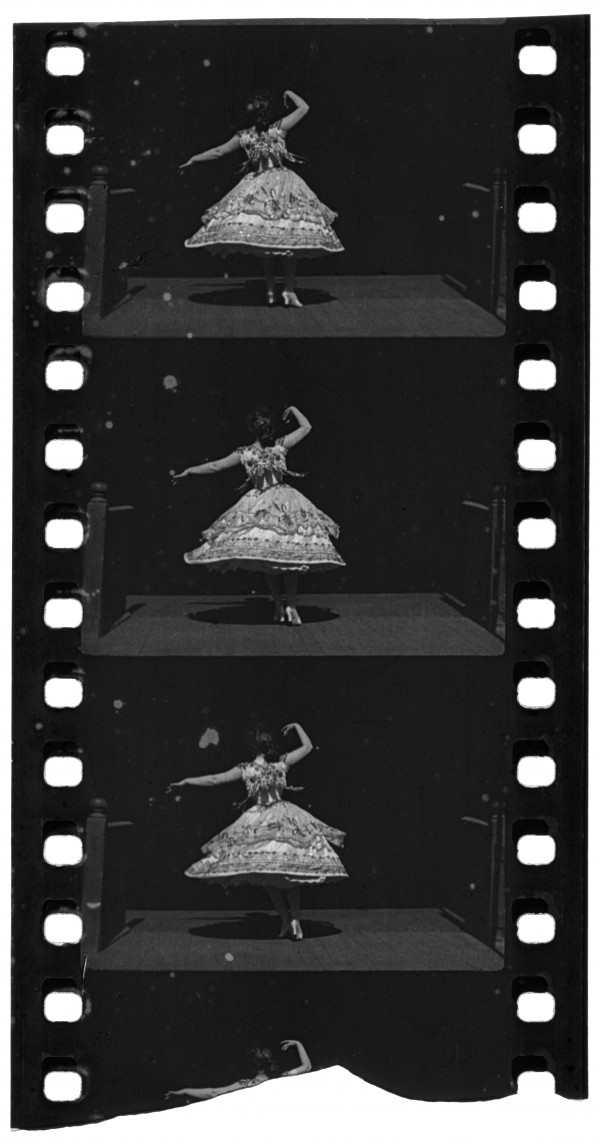

A 35mm B/W print of Carmencita (1894). Each frame was four perforations tall, giving an aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Minor variations of this frame-dimension standard were used for decades to follow.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Natural History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

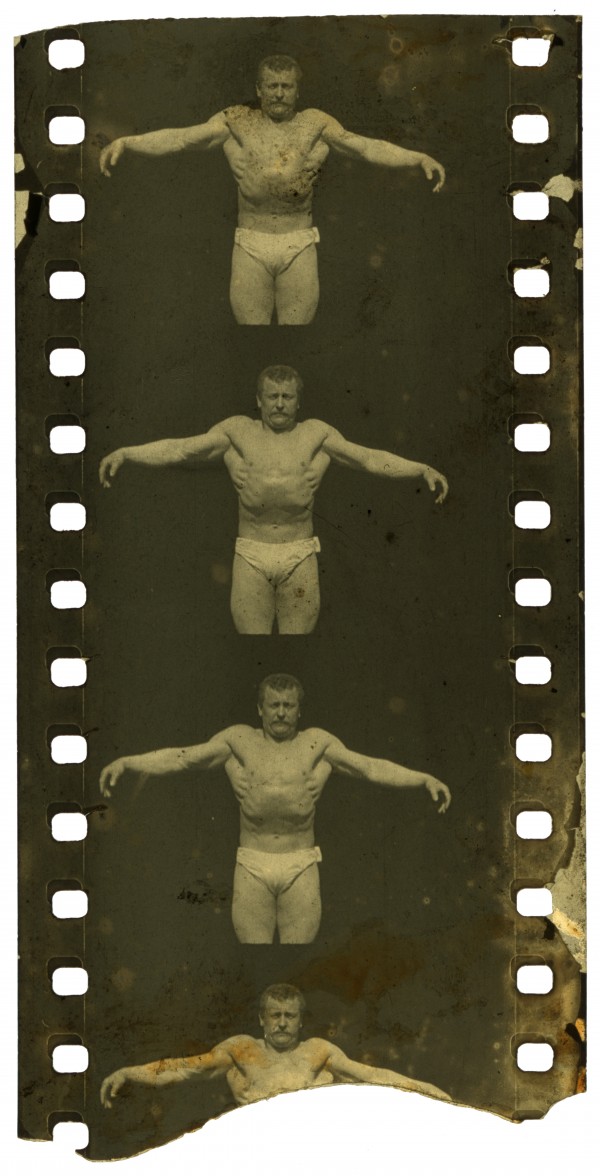

35mm B/W print of Sandow, the Strong Man (1894).

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Natural History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

Identification

During experiments in October 1891, W. K. L. Dickson asked the Eastman Company to supply films 1½-in (38.1mm) wide. Eventually, the width of film settled on was 1⅜ in (34.93mm).

B/W orthochromatic emulsion provided by the Eastman Company and Blair Camera Company.

Edges of the film around sprocket holes were black, not transparent. No markings visible.

The film stock was initially supplied by the Eastman Company and subsequently by the Blair Camera Company, from 1893–96. Because of the proximity of the illuminating light source to the viewing eyepiece, the Kinetoscope required a translucent, or frosted, rather than transparent film to diffuse the light across the frame. Historian Ray Phillips commented that “the film stock is not clear, but has the appearance of ground-glass, a sort of greyish white” (Phillips, 1997: pp. 14–15).

Most films were shot at around 38-40 fps.

1

Some films featured hand coloring.

None

The Kinetophone, commercially introduced in 1895, provided Kinetophone films with an appropriate, though not specific, phonograph accompaniment. (Not to be confused with the later Kinetophone introduced by Edison in 1910, which closely synchronized cylinder recordings with projected films.)

25.4mm x 19.05mm (1 in x 0.75 in).

B/W orthochromatic emulsion provided by the Eastman Company and Blair Camera Company.

Unknown. Likely no markings.

History

Having already astounded the world by reproducing sound with his Phonograph, Thomas Edison set his sights on representing continuous movement by means of photography. Following an inspirational meeting with the chronophotographer Eadweard Muybridge in 1888, Edison drew up preliminary designs for a motion picture viewer to be named the “Kinetoscope”. His principal assistant W. K. L. Dickson was soon enlisted to develop both the viewing device and a supplying camera (the “Kinetograph”), a task that was made easier when George Eastman began to produce thin celluloid film for use in his “Kodak” still cameras in 1889. By 1892–93 Dickson was experimenting with long lengths of celluloid cut by the Eastman Company to a width of 1½ in (38.1mm), which was slightly trimmed at the Edison works. Although Dickson was more concerned with the dimensions of the viewable image, i.e., 1 in (25.4mm) by ¾ in (19.05mm), the film-gauge measurement of 34.93mm – approximating to 35mm – was to set the industry standard for many years into the future. When faced with the possibility of different frame dimensions, Dickson elected to employ a rectangular image. The blueprint for modern film was completed when Edison, after considering various alternatives, chose to transport the film through the camera and viewer by using four sprocket holes per frame, along each side of the film.

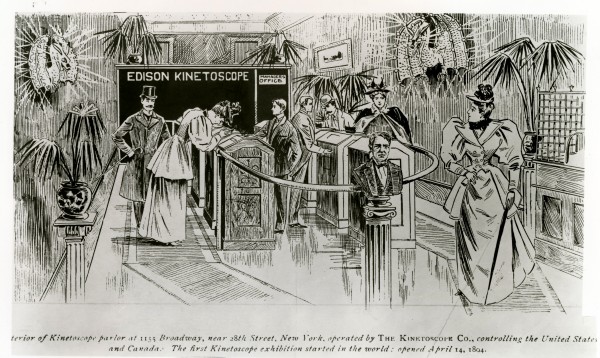

A studio, the “Black Maria”, was constructed with an opening roof that could be oriented to make full use of available sunlight. Tied to the studio by the heavy Kinetograph camera, subjects were usually around half-a-minute long and often featured variety acts, comic skits, or athletic episodes. Although the possibility of projection had been widely discussed, Edison elected to present his films in the Kinetoscope viewer, a peepshow device that owed its rationale to coin-operated Phonographs. A prototype was first publicly exhibited at Edison’s laboratory on 20 May 1891, with a redesigned device being demonstrated at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences on May 9, 1893. In readiness for public exhibition, film production was stepped up, with Dickson and William Heise filming around 75 subjects during 1894 (Musser, 1994: pp. 87–166). The Edison Manufacturing Company assumed responsibility for producing motion pictures and hardware, whilst marketing was in the hands of the Kinetoscope Company, a consortium that included Alfred O. Tate (Edison’s former business manager), Norman C. Raff, Frank R. Gammon, and the Canadian entrepreneur Andrew M. Holland. Along with his brother George, Holland became the Kinetoscope’s first commercial exhibitor, opening a ten-machine parlor at 1155 Broadway, New York, on April 14, 1894.

By the end of the year, the Continental Commerce Company acquired the rights to promote Edison’s Kinetoscope outside the United States and Canada, but not before devices purchased earlier had already been exhibited in Europe. Greek-American entrepreneurs George A. Georgiades, Demetrius Georgiades, George John Tragidis and George Malamakis purchased several Kinetoscopes and brought at least one of them to Paris where they opened an exhibition in June 1894. While continuing with the French business, they opened a London parlor in competiton with the Continental Commerce Company, whose public exhibitions had commenced at 70 Oxford Street on October 18, 1894. Despite the Continental Commerce Company’s efforts to control the sale and distribution of Kinetoscopes, the high purchase price of their proprietary machines quickly led to lower-priced copies appearing on the market. Within a few months the company’s attempts to restrict the sale of Edison-made films to purchasers of their own machines resulted in the independent Kinetoscope manufacturer Robert W. Paul collaborating with Birt Acres to create Britain’s first practical movie camera.

The popularity of the Kinetoscope was beginning to recede in North America and Europe by the time exhibitors were trying their luck in other parts of the world. Five machines were sent from London to Australia where they gave the first public show on 30 November 1894. The first exhibitions were given in South Africa in April 1895, while the Kinetoscope did not reach India until the winter of 1895/96. The first show in Japan occurred as late as 17 November 1896.

The “Wizard” Edison contrived to pull the financial rug from beneath his own feet by arousing public interest with colourful predictions of projected film while continuing to offer the distinctly small-scale viewing experience of the Kinetoscope peepshow. As 1895 progressed, the device’s failing novelty value, combined with high running costs, brought about a steady commercial decline. The writing, or rather the picture, was on the wall for the Kinetoscope as early as May 1895 when the Latham family (with covert assistance of W. K. L. Dickson) first publicly exhibited their Eidoloscope projector in New York. Edison finally bowed to the inevitable by launching the Vitascope projector (invented by Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat) in April 1896, but not until several other devices had been successfully exhibited in Europe and the United States. Unlike the manually operated Mutoscope viewer with its paper prints which remained a source of entertainment for many years, the electrically driven Kinetoscope was soon abandoned. Edison’s bookkeeper, John Randolph, testified that by December 8, 1899, 973 Edison Kinetoscopes had been manufactured, a figure which may eventually have exceeded 1,000. Of these, Ray Phillips has estimated that only nine Kinetoscopes and three Kinetophones survive (Phillips, 1997: p. 98). Although not entirely suitable, Edison-made Kinetoscope films often featured in early projected film exhibitions. About 135 to 150 Edison Kinetoscope films were made in the United States, with a smaller number filmed in the United Kingdom and Germany by Birt Acres.

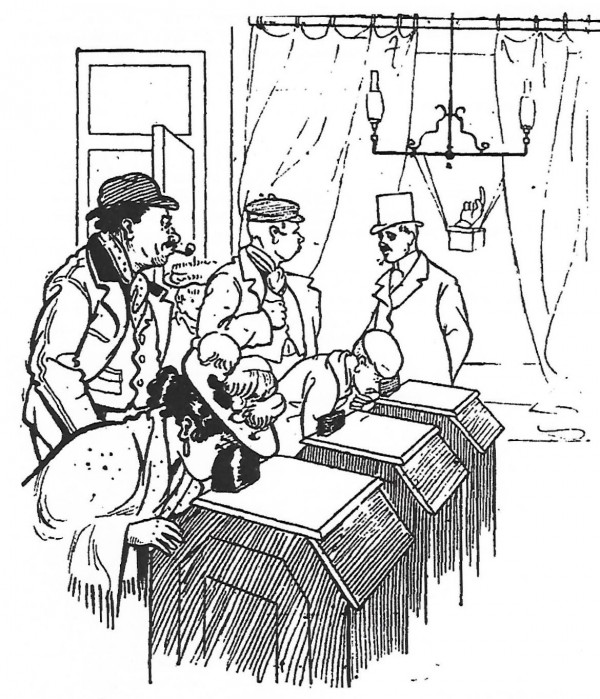

Interior of the first Kinetoscope parlor at 1155 Broadway, New York City.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Interior of Peter Bacigalupi’s Edison Kinetoscope, Phonograph and Graphophone Arcade, 946 Market Street, San Francisco, CA, United States.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Robert W. Paul replica Kinetoscopes on view at 39 Leather Lane, London, in May 1895.

Barry Anthony Collection.

Selected Filmography

The first of several dances performed for the Kinetoscope by Annabelle Whitford. An original copy survives at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, MI, and was preserved by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Another copy also survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

The first of several dances performed for the Kinetoscope by Annabelle Whitford. An original copy survives at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, MI, and was preserved by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Another copy also survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

Fancy shooting by one of the stars of Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” show. An original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

Fancy shooting by one of the stars of Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” show. An original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

A staged scene showing three blacksmiths hammering iron and drinking beer. An original copy survives at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, MI, and was preserved by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Copyrighted as The Blacksmith Shop.

A staged scene showing three blacksmiths hammering iron and drinking beer. An original copy survives at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, MI, and was preserved by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Copyrighted as The Blacksmith Shop.

Performance by a Spanish dancer who became the first woman to appear before Edison’s motion picture camera. An original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

Performance by a Spanish dancer who became the first woman to appear before Edison’s motion picture camera. An original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

A boxing contest featuring Peter Courtney and the world heavyweight champion James J. Corbett. Six 150-ft (45m) films were shot, each one representing a round of the fight. An original copy survives at the Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, United States.

A boxing contest featuring Peter Courtney and the world heavyweight champion James J. Corbett. Six 150-ft (45m) films were shot, each one representing a round of the fight. An original copy survives at the Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, United States.

The English horse race filmed by Birt Acres for Robert W. Paul’s version of the Edison Kinetoscope. Preserved by the BFI National Archive, London.

The English horse race filmed by Birt Acres for Robert W. Paul’s version of the Edison Kinetoscope. Preserved by the BFI National Archive, London.

W. K. L. Dickson welcomes viewers to his invention in a film taken by an experimental horizontally fed camera. Survives at the Thomas Edison National Historic Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

W. K. L. Dickson welcomes viewers to his invention in a film taken by an experimental horizontally fed camera. Survives at the Thomas Edison National Historic Park, West Orange, NJ, United States.

An open-air scene, employing stop-action to represent the unfortunate queen’s head falling from the block. 35mm preservation copies survive at the Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, and The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY.

An open-air scene, employing stop-action to represent the unfortunate queen’s head falling from the block. 35mm preservation copies survive at the Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, and The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY.

Publicity claimed that the 34 persons shown were “the largest number ever shown as one subject in the Kinetoscope”.

Publicity claimed that the 34 persons shown were “the largest number ever shown as one subject in the Kinetoscope”.

An early dramatic scene showing firemen enveloped in clouds of smoke. An original copy survives at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

An early dramatic scene showing firemen enveloped in clouds of smoke. An original copy survives at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

A second version of a subject first filmed in 1893. Some Kinetoscope subjects were reshot when the original negative wore out. An original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

A second version of a subject first filmed in 1893. Some Kinetoscope subjects were reshot when the original negative wore out. An original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

Filmed on March 6, 1894, this film of a strongman flexing his muscles has been described by film historian Paul Spehr as “the start of the American film industry”. Two original copies survive at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, MI, and The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Both copies have been preserved by MoMA. Another original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

Filmed on March 6, 1894, this film of a strongman flexing his muscles has been described by film historian Paul Spehr as “the start of the American film industry”. Two original copies survive at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, MI, and The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Both copies have been preserved by MoMA. Another original copy survives at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Leeds, United Kingdom.

Technology

The Kinetograph camera used 35mm film and was extremely heavy, being specially weighted to provide stability. Manoeuvrability was further restricted by its dependence on a supply of electricity for motive power. It was claimed that running speeds could be set as high at 46 fps and as low as 16 fps, but it seems that most films were shot at around 38–40 fps. The 35mm films taken usually consisted of 50-ft (15m) lengths which were reduced to 42 ft (12.8m), or less, when shown as continuous loops in the Kinetoscope. Running times usually varied between about 20 and 40 seconds. In the summer of 1894, a modified Kinetoscope viewer capable of taking lengths of film approaching 150 ft (45m) was introduced, specifically to show the individual rounds of boxing contests (3 mins).

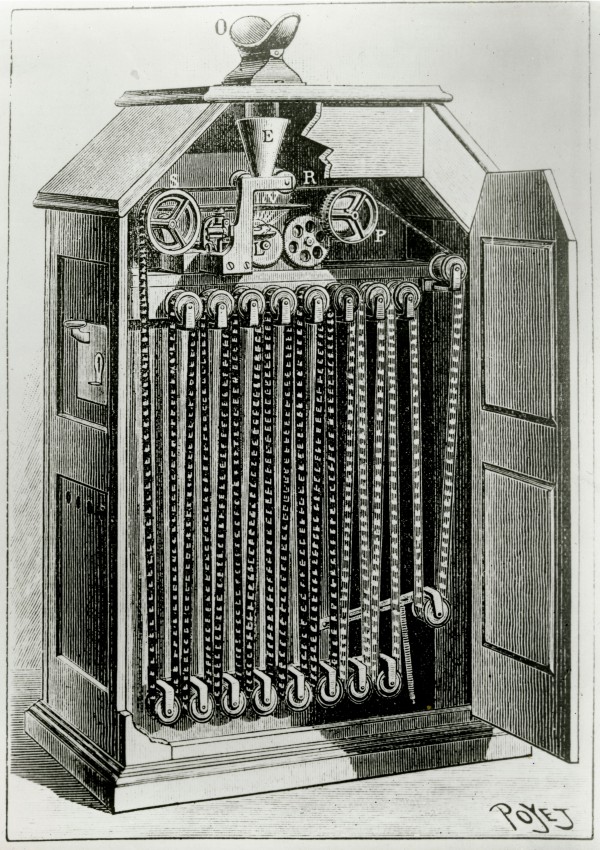

The Kinetoscope also relied on electricity for its operation, power usually being supplied by four 80 ampere-hour batteries. Inside the device’s wooden cabinet (dimensions of Kinetoscope in Eastman Museum 48.25 in high, 18.5 in wide, 27 in deep (1.23m x 0.47m x 0.69m) a band of film was joined as a loop and run over a series of rollers, past a magnifying eyepiece. The movement of film was continuous and depending on a large rotating, disc-shaped shutter, which briefly revealed each frame via a small aperture, or slit. Using the Kinetoscope was not comfortable for the viewer as they had to stand next to the cabinet and then stoop forward to look down at the film.

References

Brown, Richard & Barry Anthony (2015). The Kinetoscope. A British History. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Flicks Books.

Hendricks, Gordon (1966). The Kinetoscope. America’s First Commercially Successful Motion Picture Exhibitor. New York, NY: Beginnings of the American Film.

Musser, Charles (1997). Edison Motion Pictures, 1890–1900. An Annotated Filmography. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Musser, Charles (1994). The Emergence of Cinema. The American Screen to 1907. Berkeley, CA:University of California Press.

Phillips, Ray (1997). Edison’s Kinetoscope and Its Films. A History to 1896. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Flicks Books.

Spehr, Paul (2008). The Man Who Made Movies: W. K. L. Dickson. High Barnet: John Libbey.

Patents

Edison, Thomas A. Kinetographic Camera, US Patent 589,168, filed August 24, 1891, and issued August 31, 1897.

Edison, Thomas A. Stop Device, US Patent 491,993, filed on April 11, 1892, and issued February 21, 1893.

Edison, Thomas A. Apparatus for Exhibiting Photographs of Moving Objects, US Patent 493,426, filed August 24, 1891, and issued March 14, 1893.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Barry Anthony is a social historian with a particular interest in film and theatre. He has written extensively on many aspects of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century popular culture.

Anthony, Barry (2024). “Edison Kinetoscope”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.