An early French 35mm film format from 1896 with five perforations per frame.

Film Explorer

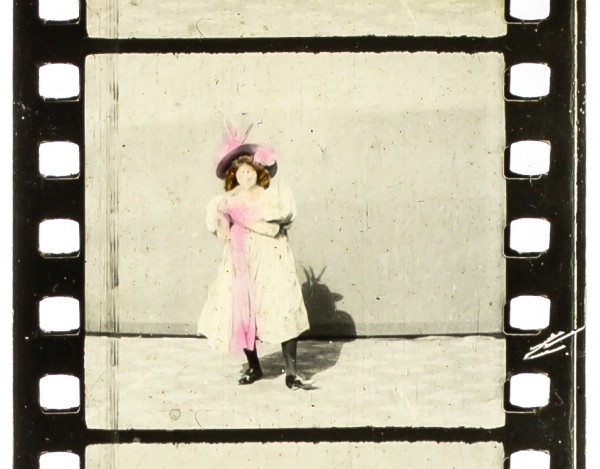

Gigue anglaise (1897). 35mm print with hand coloring. Joly-Normandin prints are distinctive because the frame is five perforations tall.

Tangible Media Collection, Ithaca, NY, United States. Courtesy of John Wallace.

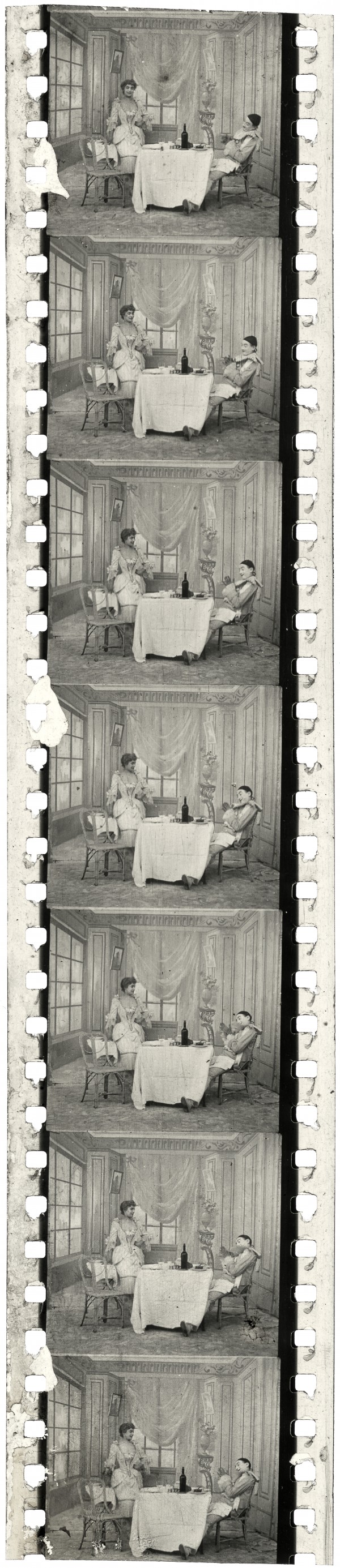

Le Déjeuner de Pierrot (Eugène Pirou, winter 1896–1897).

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

La Bataille de fleurs de Nice (Eugène Pirou, spring 1897). An actuality film shot in the south of France.

Filmoteca Española, Madrid, Spain.

Identification

Approx.

B/W

None. Some prints feature clear edges with thick black frame lines on both sides of the image. On other prints, the edges are entirely black.

1

Some B/W copies were hand coloured.

None

None

c. 24mm x 22.8mm (c. 0.94 in x 0.90 in).

B/W

History

On March 17, 1896, engineer Henri Joly patented a new cinematographic device which had the peculiarity, at a time when many different systems were being proposed, of employing 35mm film, but in an almost-square format, with five perforations per frame rather than four. Joly was soon contacted by engineer Ernest Normandin, who offered to commercialise the device – Normandin apparently also suggested certain technical improvements. The duo’s first films were shot during the summer of 1896, probably in the context of the upcoming Exposition internationale du théâtre et de la musique, where Normandin and the camera manufacturer Louis Doignon were the only ones presenting a cinematograph and were both awarded a diploma of honour. Patent applications were soon made in France, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Normandin’s ambition to expand is evident in the advertisements he took out in the international press and his forging of links with foreign exhibitors. Normandin needed new films to supply to exhibitors along with his system, because, at least initially, the system was not compatible with films on offer from other firms due to its use of five perforations per frame. Normandin's catalogue offered titles shot by exhibitors in France and abroad, but his commercial relationship with these “exhibitor-operators” remains unclear. It is not known whether he shared the profits from the sale of prints with them.

By the first months of 1897, there were at least a dozen Joly-Normandin cinematographs operating in France and abroad (United States, Germany, Australia, Ireland, Spain, Italy). At the end of March 1897, Normandin decided to lower the price of the apparatus, and in May he was invited to organise some screenings as part of a cinematographic attraction at the Bazar de la Charité in Paris, a charity event intended to gather the whole of Parisian high society. But the whole set-up at the Bazar was somewhat precarious and potentially hazardous: hosted in a huge wooden hanger crowded with painted scenery and a reconstructed “Old Paris” made from papier-mâché and fabrics, about twenty stalls, a buffet and a space for the cinematograph booth. Safety measures were inadequate – reduced to the absolute minimum stipulated by the police prefecture. Normandin, given very short notice, set up his cinematograph on May 4, after the opening of the Bazar. As there was no electricity supply, an Alfred Molteni oxy-ether lamp was used and projection was entrusted to his employees Bellac and Grégoire Bagrachow. The theatre was full when a handling error by Bellac and Bagrachow caused a fire that spread rapidly through the building. The turnstile at the entrance to the hall prevented the swift evacuation of the audience. Disaster was inevitable: 126 people died and many more were injured – most by burns.

Normandin, even if not held responsible for the fire, inevitably came to be associated with the drama. Unfortunately for him, on June 14, 1897, his apparatus, installed at the Eden Musée in New York City, also caught fire. The incident was minor and there were no victims, but the Joly-Normandin cinematograph was forced to leave the Musée. A few months later, in August, the cinematograph installed above the performance venue Parisiana in Paris resulted in another fire. Although fire damage to the buildings appeared to be considerable, there were no injuries or deaths. Three fires in four months were too much for Normandin to handle. Advertisements for the Joly-Normandin cinematograph became increasingly rare in the French press, and in the latter months of 1897 the Cinématographe Joly-Normandin was mainly to be found abroad.

Ernest Normandin decided to sell all the equipment, patents and exploitation of the “Cinématographe perfectionné, système Joly” to Alfred Saunier and Charles Flahault. A new company was formed on April 22, 1898, and on August 24, 1898, Edgard Normandin (Ernest’s brother) registered the trademark “The Royal Biograph”. In October 1899, Edgard Normandin joined forces with Rodolphe Fouchier in order to buy, sell and exploit cinematographs and their accessories. But the company would not survive for long, and it was declared bankrupt in June 1901. The company briefly became “Fouchier, Normandin et Cie” but was dissolved in December 1901.

Selected Filmography

Technology

The Cinématographe Joly-Normandin was a dual camera and projector – it was among the first to use perforated film. The qualities of the device were praised in several scientific publications. These included: toothed rollers that engaged with the film and allowed loops to be formed (minimising tension); a much brighter image and less flickering; and larger images (the almost-square frame was five perforations tall). The device was sold as being ideal for projection in larger theatres. Henri Joly also designed a perforating machine and a copying machine (printer). Construction was entrusted to Albert Doignon, an engineer at Arts et Manufactures.

Several newspapers reproduced an identical description of the device, probably communicated by the manufacturer:

“It is in fact a sort of magic lantern, whose glass strips are replaced by a transparent film strip on which 1,200 to 1,500 photographs of an eventful scene are printed. The hundreds of photographs were taken successively over a period of about 1 minute and 20 seconds, at a speed of 15 photographs per second. In this way it was possible to capture different phases of the fastest movements, while the still objects are reproduced absolutely identically in each photograph. The film strips, which are between 15 and 16 metres long, are wound onto a cylinder which is placed in the camera and operated by high-precision gears, so that the film strip is unwound at a certain speed and then wound onto another cylinder which receives the same impulse as the first.”

Normandin and Joly also proposed other models: a “Cinématographe petit modèle” (“small model”), with a mechanism based on a ratchet wheel; and a “Cinématographe de famille” – a smaller model, “allowing animated views to be taken during journeys and projected at home”.

References

Associazione Giornate del cinema muto (2013). Le Giornate del cinema muto 2013 (32), October 5–12 2013 (filmography of the titles located in archives), pp. 155–161. Pordenone: Associazione Giornate del cinema muto. http://www.cinetecadelfriuli.org/gcm/ed_precedenti/edizione2013/immagini_2013/GCM2013_Catalogo_w_REV.pdf

Blot-Wellens, Camille (2014). El cinematógrafo Joly-Normandin (1896–1897). Dos colecciones: João Anacleto Rodrigues y Antonino Sagarmínaga. Madrid: Filmoteca Española, Ministerio de Cultura. https://www.calameo.com/read/00007533591cd2141932c

Brunel, Georges (1897). La Photographie et la projection du mouvement, pp. 79–91. Paris: Mendel.

Brunel, Georges (1897). La Projection du mouvement. Historique, dispositifs; le cinématographe-Normandin, par Georges Brunel. Paris: Normandin.

Breton, Jules-Louis (1898). La Chronophotographie, la photographie animée, analyse et synthèse du mouvement, par J.-L. Breton, pp. 195–198. Paris: E. Bernard.

Hennion, Jean Baptiste (2002). “L’Emergence des machines cinématographiques: la contribution d’Henri Joly (1895–1896)”. DEA dissertation, Université Paris VIII – UFR Arts, Philosophie & Esthétique, Département d’études cinématographiques et audiovisuelles.

Huret, Jules (n.d.). In memoriam. La Catastrophe du Bazar de la Charité (4 mai 1897). Historique du Bazar de la Charité, la catastrophe, les victimes, les sauveteurs, les blessés, les funérailles, détails rétrospectifs, les responsabilités, liste officielle des récompenses, etc., liste complète des souscripteurs du “Figaro”: documents recueillis et mis en ordre par Jules Huret, pp. 153–155. Paris: F. Juven.

Lange, Eric (2008). “Henry Joly”. http://cinematographes.free.fr/joly.html (accessed April 7, 2024).

Mannoni, Laurent & David Robinson (1995). Le Grand art de la lumière et de l'ombre: archéologie du cinéma, p. 397. Paris: Nathan.

Meusy, Jean-Jacques (2016). Paris-Palaces ou Le temps des cinémas, 1894-1918, pp. 50–51. Paris: Nouveau Monde.

Mollier, Etienne (1947). “Souvenirs sur Henri Joly et les premiers essais de cinéma sonore”. Bulletin de l’AFITEC, 1: pp. 7–10.

Noverre, Maurice (1929). “Notice biographique de M. Joly”. Le Nouvel art cinématographique, 3:2 (July): pp. 62–63.

Trutat, Eugène & Étienne-Jules Marey (1899). La Photographie animée, par Eug. Trutat ... avec une préface de J. Marey, pp. 82–87. Paris: Gauthier-Villars.

Mannoni, Laurent (1996). “Repères biographiques sur Henri Joly, l'initiateur technique de Charles Pathé”. 1895, revue d'histoire du cinéma, 21, “Du côté de chez Pathé (1895–1935)”: pp. 16–38. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3406/1895.1996.1193

Patents

Joly, Marie Joseph Henri. 1896. Appareil chronophotographique pouvant également servir à la projection des positifs. French Patent FR254836, issued March 17, 1896.

Joly, Marie Joseph Henri. 1896. Chronophotographic Apparatus. US Patent US569875A, issued October 20, 1896.

Joly, Marie Joseph Henri. 1896. Appareil servant à impressionner les pellicules positives employées dans les appareils chronophotographiques. French Patent FR261526, issued November 23, 1896.

Joly, Marie Joseph Henri. 1897. Kinetographic Camera. US Patent US574851A, filed October 16, 1896, and issued January 5, 1897. https://patents.google.com/patent/US574851A/

Joly, Marie Joseph Henri. 1897. Improvements in Chrono-photographic Apparatus adapted for the Projection of Positives upon a Screen. British Patent GB189621381A, filed September 26, 1896, and issued September 11, 1897. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/032339554/publication/GB189621381A?q=pn%3DGB189621381A

Joly, Marie Joseph Henri. 1897. Improvements in Chrono-photographic Apparatus. British Patent GB189621382A, filed September 26, 1896, and issued September 11, 1897. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/032339555/publication/GB189621382A?q=pn%3DGB189621382A

Joly, Marie Joseph Henri. 1897. An Apparatus for use in Exposing the Positive Films used in Chrono-Photographic Apparatus. British Patent GB189621383A, filed September 26, 1896, and issued September 4, 1897. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/032352009/publication/GB189621383A?q=pn%3DGB189621383A

Compare

Author

Camille Blot-Wallens is an independent film historian, researcher, and archivist. She studied History at University Paris 1 and Film Archives at University Paris 8 and the European program Archimedia. She started collaborating with Filmoteca Española in 2000 as independent researcher, and more specifically on the identification and analysis the Sagarmínaga Collection (1895-1906) together with Encarni Rus Aguilar and the Joly-Normandin films of the Sagarmínaga collection and Anacleto Rodrigues Collection from Cinemateca Portuguesa. Alongside, she obtained the grant Lavoisier from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2001) to assist Luciano Berriatúa on the restoration of Der letzte Mann (F. W. Murnau, 1925) and continued working with him on other Murnau’s films for the Murnau-Stiftung. In 2007, she joined the Cinémathèque française as Head of the Films Collections. Since 2012, she has been an independent researcher and historian residing in Stockholm, where she works on restoration and research projects for European and International archives. Member of the FIAF Technical Commission since 2012, she takes part to numerous trainings for archivists, and she recently edited a new, enriched edition of Harold Brown’s Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification for FIAF (2020). Camille is also associate professor at the University Paris 8 Vincennes – St-Denis, where she is co-responsible of the Master in Film Studies, Specialisation Film Heritage, and she is also a lecturer at University of Lausanne where she runs a workshop on conservation and restoration as part of the Cinema Network (Réseau Cinéma CH). In 2018, she was recipient of the Jean Mitry Award (Giornate del cinema muto, Pordenone – Italy) and of the The Outstanding Achievement Award for Film Preservation (Film Heritage Foundation, Mumbai – India). In 2019, she was invited to honour Film Preservationist Harold Brown giving the Jonathan Dennis Memorial Lecture during Il Giornate del cinema muto and the Ernest Lindgren Lecture at the British Film Institute.

Alfonso del Amo, Chema Prado (then at Filmoteca Española); Tiago Baptista, Rui Machado and Jose Manuel Costa (Cinemateca portuguesa); Laurent Mannoni, Joël Daire (Cinémathèque française); Bryony Dixon (British Film Institute); Jon Wengström (Svenska Filminstitutet) as well as Denis Condon, Roland Cosandey, Maurice Gianati, Eric Lange, Tony Martin-Jones, Jean-Jacques Meusy, Charles Musser, Deac Rossell.

Blot-Wellens, Camille (2024). “Cinématographe Joly-Normandin”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.