A groundbreaking, multiscreen film event at Expo 67 in Montreal, Canada, that exemplified the concept of cinema as an all-encompassing environment.

Film Explorer

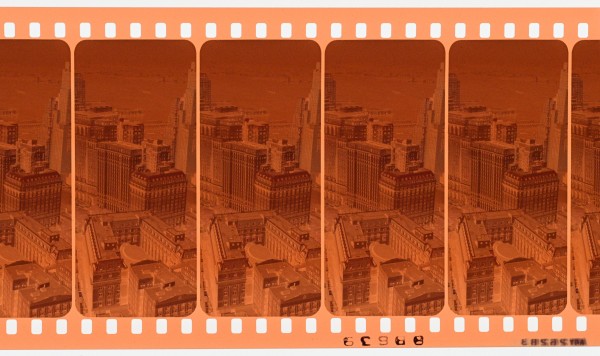

Chamber 1 of Labyrinth featured two panels of vertical images (one projected onto an upright screen, and the other onto a screen mounted horizontally on the floor) from 70mm prints in synchronization. Both the 65mm camera negative (seen here) and the 70mm prints were advanced horizontally.

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Special thanks to Marie-France Rousseau, Cecilia Ramirez, Steve Hallé and Adam Abouaccar.

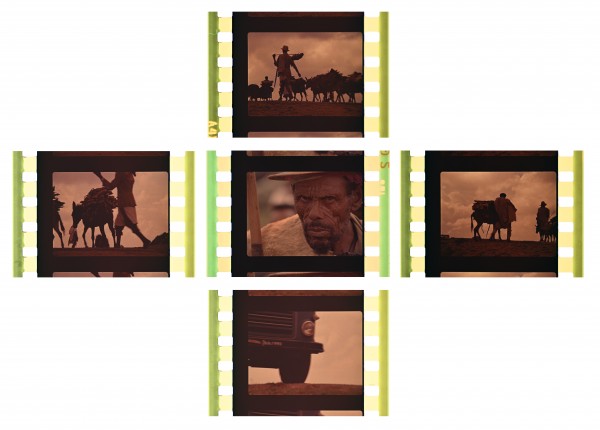

Chamber 3 of Labyrinth presented a cruciform screen consisting of five 35mm prints projected in synchronization.

Identification

70mm (Chamber 1); 35mm (Chamber 3).

Unknown (Chamber 1); 20.96mm x 15.24mm (0.825 in x 0.600 in) (Chamber 3).

1:1.92 (Chamber 1, 70mm); 1.37:1 (Chamber 3, 35mm, five panels arranged in cruxiform).

5-perforation, horizontal (Chamber 1, 70mm); 4-perforation, vertical (Chamber 3, 35mm)

Eastman Color

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

2 (Chamber 1); 5 (Chamber 3).

Color

A separate reel of 35mm full-coat magnetic film was synchronized to the two 70mm prints in Chamber 1; an additional reel of 35mm full-coat magnetic film was synchronized to the five 35mm prints in Chamber 3.

65mm (Chamber 1); 35mm (Chamber 3).

70.41mm x 52.61mm (2.772 in x 2.032 in) (Chamber 1); 22.05mm x 16.03mm (0.868 in x 0.631 in) (Chamber 3).

5-perforation, horizontal (Chamber 1, 65mm); 4-perforation, vertical (Chamber 3, 35mm)

Eastman Color

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

History

The Labyrinth project, a groundbreaking, multiscreen film event at Expo 67, exemplified the concept of cinema as an all-encompassing environment. Expo 67, one of the most successful World Fairs, was held in Montreal, Canada, from April 27 to October 29, 1967, and showcased architectural marvels and expanded cinema and media experiments. The Expo theme was “Man and His World” – the event celebrated human progress and cultural exchange. Expo 67 played a significant role in promoting Canadian culture and placed Montreal on the World map. Labyrinth was housed in a purpose-built structure, unlike other film presentations at the exposition. It was designed to immerse viewers in a highly choreographed cinematic experience across three distinct spaces, or “chambers”, two of which contained unique, multiscreen theatre designs. This project demonstrated the National Film Board of Canada’s (NFB) pioneering artistic and technological innovation achievements.

The Labyrinth project was conceived by renowned documentary filmmakers Colin Low and Roman Kroitor, from Unit B of the NFB, and was five years in the making. Unit B produced short documentaries for Canadian television, starting with The Candid Eye series in the 1950s. These films were shaped by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s realist aesthetics, capturing everyday life in a “decisive moment”.

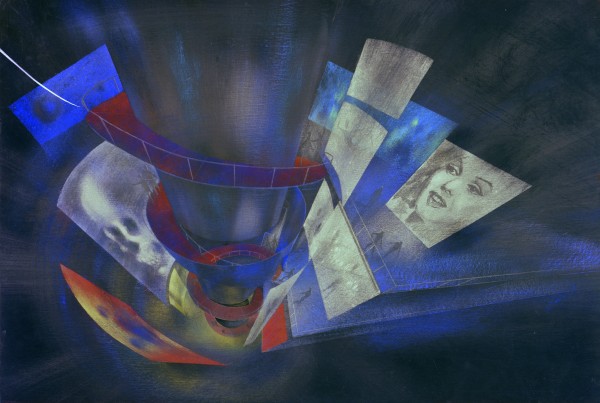

For Labyrinth, Low drew inspiration from Mary Renault’s 1958 novel, The King Must Die, a popular reinterpretation of the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur – the half-man, half-bull creature that resided within the Labyrinth, at Knossos in Crete. In the myth, Theseus navigates the labyrinth by following Ariadne’s thread and slays the Minotaur. In collaboration with Northrop Frye, Low and Kroitor used this myth as a framework for a narrative centered on self-realization, portraying the Minotaur as a metaphor for the inner struggles we must overcome. Their goal was to craft a “ritual” or “artistic” experience designed to evoke a transformative “state of mind”. Like the 1955 Family of Man photographic exhibition (at MoMA in New York), the Labyrinth project emphasized humankind’s shared experiences and commonalities.

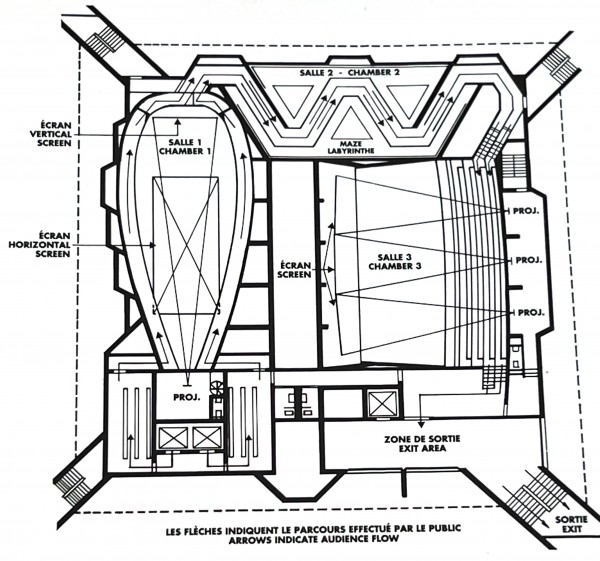

The Chambers

The Labyrinth journey began in Chamber 1, titled “Childhood, Confident Youth”, and was a theater space unlike any other. Its design featured two enormous 70mm screens: one orientated vertical, rising 38 ft (11.6m) from the ground, and one horizontally placed, which stretched across the floor beneath. Audience members sat on balconies arranged in a horseshoe formation, gazing up at the towering vertical screen, while simultaneously looking down at the horizontal, ground-level display. The dual-screen setup, enhanced by a sophisticated audio system with 5 independent sound channels, played through 288 strategically placed speakers, created an overwhelming sense of immersion. The interplay of sound and image, combined with the physical demands of shifting gaze between the two enormous screens, evoked a powerful sense of movement through space. This chamber served as a dynamic introduction, establishing the experimental and boundary-pushing nature of the pavilion.

The experience then shifted to Chamber 2, known as “The Maze”, or “The Desert”, which journalist Wendy Michener described as akin to an “acid trip”. Designed by Colin Low, this octagonal room was lined with mirrors on every surface – walls, floor and ceiling – and contained three glass prisms with half-silvered surfaces. When illuminated, the prisms reflected a seeming infinity of lights, creating a cosmic visual effect that dissolved the boundaries of the space. The audience became part of the spectacle – their images were reflected and fragmented endlessly in the mirrors. A soundtrack of electronic tones mixed with animal sounds further heightened the surreal, disorienting atmosphere. Lights flashed and multiplied through the glass while the mirrored passageways zigzagged, reinforcing the sensation of space without end. This chamber sought to dissolve the boundaries between human and nonhuman, self and other – enveloping visitors in a boundless, acoustic and visual cosmos.

The final chamber, Chamber 3, titled “Death/Metamorphosis”, was a fixed-seated theater, where 35mm images were projected onto five screens arranged in the shape of a cross – a symbolic reference to the tree of life. Here, the immersive multiscreen techniques reached their apex. Films showcased cultural rituals and everyday life worldwide, including a crocodile hunt in Ethiopia, a baptism in Greece, childbirth in Montreal and snow-covered streets in Quebec. These scenes were accompanied by a richly layered soundtrack combining location audio, voiceover and a score composed by NFB’s Eldon Rathburn. The vertical editing style, devised by producer Tom Daly, allowed images to flow across multiple screens, creating moments of striking visual poetry. This compositional approach prevented sensory overload, while encouraging viewers to form subconscious associations. Colin Low described the multiscreen format as a gateway to the “ultimate image”, imagining a future where images would become electronic, stereoscopic, or even holographic.

The film budget for Labyrinth was CA$4.5 million. Among the most popular attractions at Expo 67, with wait times of up to seven hours, the films were seen by 1,324,560 people and ran for 5,545 shows. With the Labyrinth project, Low and Kroitor envisioned an entirely new audiovisual experience – an expanded form of cinema they believed could redefine the medium’s future. Their innovative approach transformed cinematic storytelling at the time and laid the foundation for new technological developments in screen design. Kroitor worked with filmmaker Graeme Ferguson to create IMAX (IMAGE MAXIMUS) for the Osaka Expo in 1970. Low later contributed to the evolution of IMAX 3D with his film Transitions for the Vancouver Expo in 1986.

Media theorist Gene Youngblood later described Expo 67's pioneering experiments, including Labyrinth, as examples of “expanded cinema”, heralding a new visual language that continues to influence filmmaking today.

The Labyrinth Project imagined by director Colin Low, 1963.

Colin Low Fonds, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

An exterior view of the Labyrinth at Expo 67, Montreal, Canada.

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

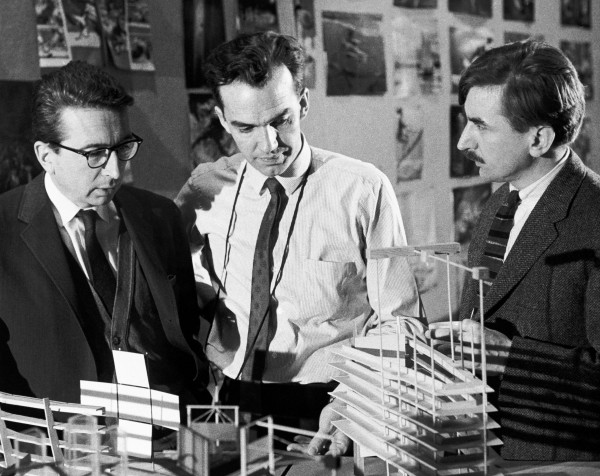

Hugh O’Connor, Colin Low and Roman Kroitor with the maquette of the Labyrinth Pavillion.

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Floor plan depicting the three chambers.

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Technology

The National Film Board of Canada was, at this time, at the forefront of technological advancements, particularly in sound recording, film camera design and projection systems. These innovations enhanced the mobility and versatility of filmmaking, enabling projects like Labyrinth to push the boundaries of cinematic form and viewing, producing highly interactive environments. Labyrinth’s multiscreen format and environmental design epitomized the NFB’s vision of integrating film, technology and storytelling into a spectacular, immersive experience. The “quest for mobility”, as Gerald Graham (director of technical operations and research at the NFB, 1944–64) described it, was exemplified by the advent of synchronous sound-recording technology in 1955. This innovation allowed for greater flexibility in location shooting and bolstered the NFB’s reputation in direct cinema. Another significant breakthrough, developed for Expo 67, was large-screen projection technology using 70mm and 35mm film, which later evolved into IMAX’s 70mm film projection system.

In Chamber 1, visitors were transported by elevator to one of four levels, each with eight balconies. The theatre was designed in a horseshoe formation, with the two screens arranged in an L shape. From the four tiers of eight balconies, viewers gazed out at a vertical screen that rose 38 ft (11.6m) from the ground, and looked down at the long horizontal screen on the floor. Five large theatre speakers were placed behind the screens, and a surround-sound experience was created via 288 smaller speakers, placed strategically throughout the balconies. This arrangement ensured that the sound amplified the visual and spatial depth of the images.

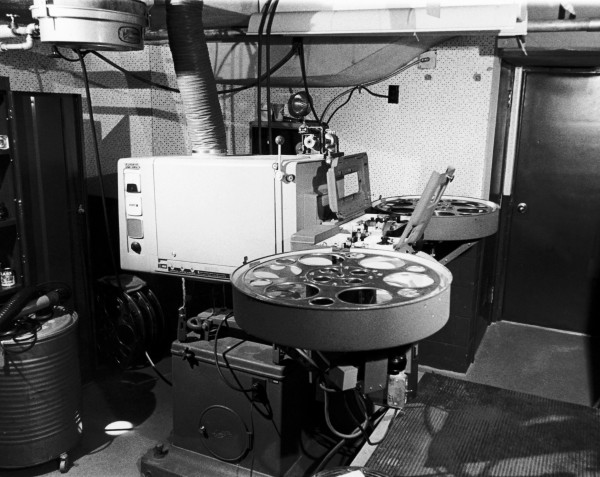

70mm prints were used for both screens. Some images projected across both screens and were part of the same scene; while other arrangements presented contrasting views. To support this effect, the NFB engineers chose two 70mm JJ-3 projectors fitted with Hughs 5KW Xenon lamp housings and Panavision-Steinheil 95mm lenses. As the NFB technical bulletin reports, the projectors featured “positive lubrication systems”. These projectors were carefully chosen since one needed to operate pointing “face down” towards the horizontal screen on the floor, and the other placed on its side for the vertical, deeply portrait-oriented screen. Plain white matt screen material was chosen to accommodate some of the extreme viewing angles from the wildly different viewing positions in the theatre. Since this material needed to be replaced regularly, a special mounting system was designed to facilitate easy removal and cleaning (NFB, 1968).

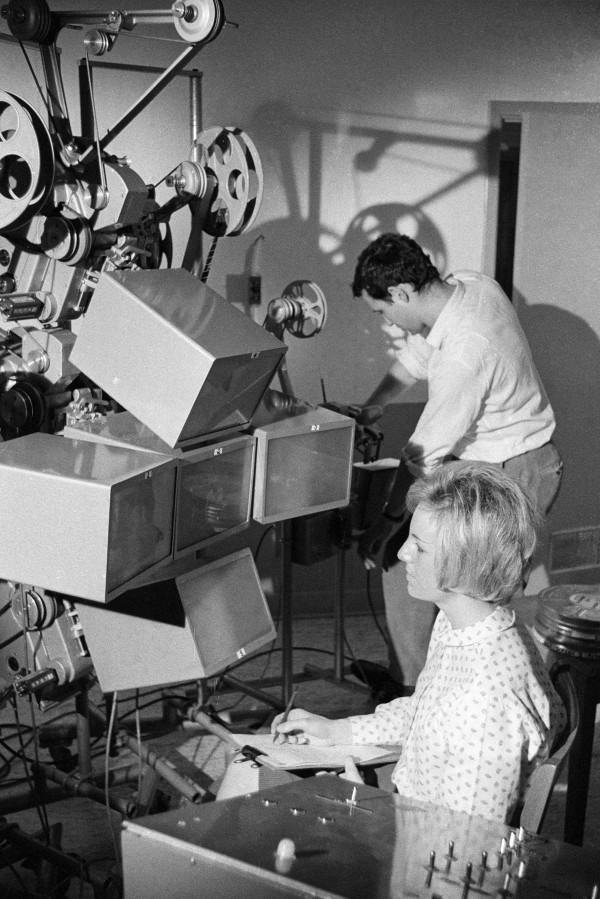

For Chamber 3, the NFB created a synchronous multicamera setup consisting of five Arriflex 35mm cameras mounted in a cruciform arrangement, with a 9.5-in (24.13cm) distance between the lenses for optimal shared perspective. These cameras could be operated in various combinations, recording unified, or disparate images, and the resulting films were projected using five Century WMDA 35mm projectors synchronized and arranged similarly. Both the camera and projection systems were adaptations of television studio switching technology – as an example, the cameras operated on “Syncontrol”, an electrical interlock system devised by the NFB.

An interior view of the audience watching one of two massive screens in the first chamber of the Labyrinth Pavilion.National Film Board of Canada, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

One of the Century JJ-3 horizontal 70mm projectors used in Chamber 1.

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

The special 35mm editing system designed for editing the cruciform film for Chamber 3.

Chamber 3 screen prototype, built and tested in an airplane hangar.

References

Douglas, Creighton, R.R. Epstein and P. Mundle. “The Labyrinthe Pavilion at Expo 67.” Paper no 59, SMPTE 102nd Technical Conference Program, 1967.

Expo 67 (1967). Expo 67: Official Guide. Toronto: Maclean-Hunter.

Frye, Northrop (1963). Fables of Identity: Studies in Poetic Mythology. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Glassman, Marc & Wyndham Wise (1999). “Interview with Colin Low, Part I”. Take One, 23: pp. 29–40.

Glassman, Marc & Wyndham Wise (2000). “Interview with Colin Low, Part II”. Take One, 26: pp. 22–32.

Marchessault, Janine (2007). “Multi-Screens and Future Cinema: The Labyrinth Project at Expo 67”. In Fluid Screens: Expanded Cinema, Susan Lord & Janine Marchessault (eds), pp. 29–51. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Marchessault, Janine (2017). “Terre des Hommes / Man and His World: Expo 67 as Global Media Experiment”. In Ecstatic Worlds: Media, Utopias, Ecology, Janine Marchessault, pp. 129–60 (Chapter 4). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Michener, Wendy (1966). “Through a Multi-Screen Darkly”. Maclean’s, 17 (Sep.): p. 58.

National Film Board of Canada Technical Operations Branch, Roman Kroitor, Colin Low et al. (1964). “Minute no. 3, Labyrinth Design Committee. Meeting” (April 11). Toronto: NFB.

National Film Board of Canada (1968). Labyrinth Technical Bulletin, 8. National Film Board of Canada Technical Operations Branch (Mar.).

Youngblood, Gene (1970). Expanded Cinema. New York: Dutton.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Janine Marchessault is a professor in Cinema and Media Arts at York University in Toronto. Her research engages with the history of large-screen media from multiscreen to IMAX to media as architecture and VR. She belongs to the CinemaExpo67.ca research group, as well as the transnational history of IMAX (1970–1990). She is the author of Ecstatic Worlds: Media, Utopias and Ecologies (2017) and numerous collections including the Oxford Handbook of Canadian Cinema, with W. Straw (2019), Process Cinema: Handmade Film in the Digital Age, with S. MacKenzie (2019), Reimagining Cinema: Film at Expo 67, with M. Gagnon (2014), Cartographies of Place: Navigating the Urban, with M. Darroch (2014).

Most of the research for this entry is drawn from (1) Marchessault, Janine (2007), “Multi-Screens and Future Cinema: The Labyrinth Project at Expo 67”. In Fluid Screens: Expanded Cinema, Susan Lord & Janine Marchessault (eds), pp. 29–51. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; (2) Marchessault, Janine (2017), “Terre des Hommes / Man and His World: Expo 67 as Global Media Experiment”, pp. 129–60 (Chapter 4). In Ecstatic Worlds: Media, Utopias, Ecology, Janine Marchessault. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Thanks to Dr. Cameron Moneo, post-doctoral researcher on the history of Imax project at York University for detailed research as well as James Layton for precise technical specifications and image research.

Marchessault, Janine (2025). “Labyrinth”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.