Film Explorer

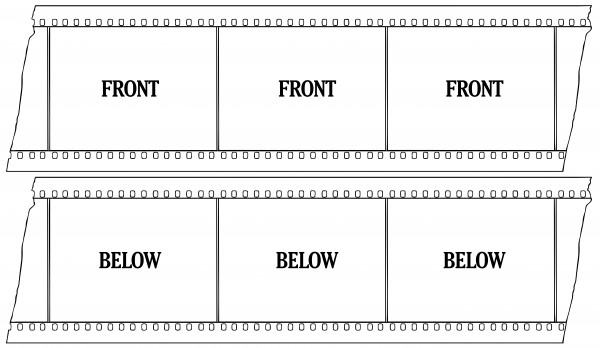

The IMAX Magic Carpet format used two 70mm prints running horizontally; one projected on the screen in front of the audience, and one projected underneath the seats.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

The IMAX format used 65mm Eastman Kodak color negative. The enormous frame was 15 perforations wide.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

Identification

History

While working on concepts for what would become the Labyrinth pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, Canadian filmmaker Roman Kroitor proposed simulating the experience of flying by building a theater with a screen under a transparent floor. Fellow filmmaker Graeme Ferguson recalls that, in 1964, he “visited the hangar at an aircraft factory where [Kroitor and filmmaker Colin Low] were carrying out the early experiments. They invited me to walk out on a very large sheet of plate glass, which turned into a magic carpet. As the lights went down, the carpet lifted off and soared above the skyscrapers of Montreal. I had nothing to hold on to, so the effect was, to put it mildly, alarming. Roman soon discovered that flying on a magic carpet made some people airsick, so they modified the design.” (Ferguson, 2016)

Ultimately, Kroitor’s design for Labyrinth put a large screen on the floor and another on a wall at the end of a long, deep room, surrounded by balconies on which the audience stood to view films projected on both screens. Following the Expo, Kroitor and Ferguson formed IMAX Corporation with business partner Robert Kerr.

By the late 1980s, World’s Fairs and theme parks had become a significant part of IMAX’s business, which gave Kroitor the opportunity to fully realize his Magic Carpet concept. Expo ’90 was held in Osaka, Japan, from April 1 to September 30, 1990, attracting more than 23 million visitors. IMAX provided no fewer than four theaters for the fair, each with a different configuration, with two using technology never seen before. (See IMAX 3D and IMAX Solido)

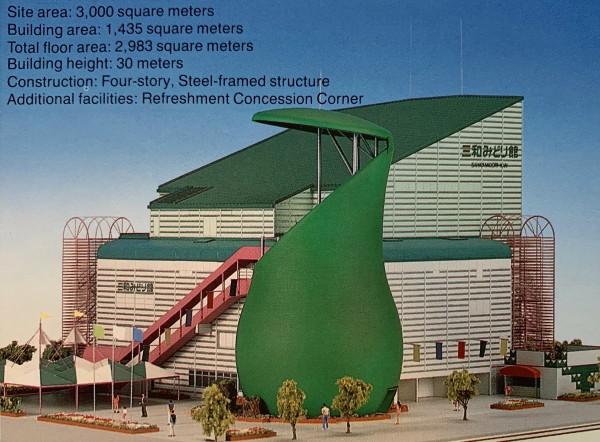

The IMAX Magic Carpet theater was built in the pavilion sponsored by Sanwa Midori-Kai, an Osaka-based banking conglomerate that also funded the US$3 million film for the theater (Konowal, 2022). Seating 294, its upper screen was 18.9 x 25m (62 x 82 ft) and the lower screen was 18.2 x 27.7m (59.7 x 90.9 ft). (IMAX, 1992) Six-channel analog audio was played back by speakers throughout the house.

In keeping with the theme of the Expo, “The Harmonious Coexistence of Nature and Mankind”, the Magic Carpet showed Flowers in the Sky, a 15-minute film about the migration of the monarch butterfly, produced by Kroitor and Charles Konowal, and directed by Michael Scott.

Shooting the film required a massive aerial rig to hold the two IMAX 15/65 cameras in positions corresponding to the orientation of the theater’s screens. In keeping with the “surprise reveal” tradition of such previous films as This is Cinerama (1955), North of Superior (1971) and To Fly (1976), Flowers in the Sky opened with the lower screen dark and a macro sequence of butterflies emerging from their cocoons on the upper screen. As the butterflies start to fly, the lower screen lit up with a POV shot of flying over the landscape, to create Kroitor’s dramatic “Magic Carpet” effect (Konowal, 2022).

Flowers in the Sky was one of the three most popular attractions at Expo ’90. The top two were also IMAX theaters (see IMAX Solido and IMAX 3D) (Konowal, 2022).

The Magic Carpet theater was demolished shortly after the Expo, along with nearly all other structures built for the fair.

In 1992, Parc du Futuroscope, France’s theme park of moving images, opened the first and only permanent Magic Carpet theater (Tapis Magique in French) and began showing Flowers in the Sky. It ran there continuously until 2003.

Futuroscope had opened near Poitiers in 1987. Its first attraction was Kinemax, an IMAX (2D) theater, and it subsequently added a theater featuring Douglas Trumbull’s Showscan system (5-perf 70mm at 60 fps) in 1988, and venues with IMAX Dome (1990), IMAX Solido (1993), IMAX 3D (1996), and IMAX Ridefilm (2000) – all in buildings with strikingly unique architecture.

In 2003, the park commissioned a new Magic Carpet film, Voyageurs du ciel et de la mer (Travelers of Sky and Sea). The 16-minute film was produced by Galatée Films and directed by Jacques Cluzaud and Jacques Perrin. Much of the film was shot with a two-camera rig. But when the filmmakers wanted the action to move from the bottom screen to the top screen, or vice versa, they used a single 15/65 camera, turned 90 degrees (i.e., portrait mode), and separated each frame into two 7.5-perf frames that were blown up to two 15/65 internegatives (Hyder, 2004). Voyageurs opened in 2004 and ran until the theater was closed in late 2014. In 2016, the building was repurposed to house a motion-simulation ride.

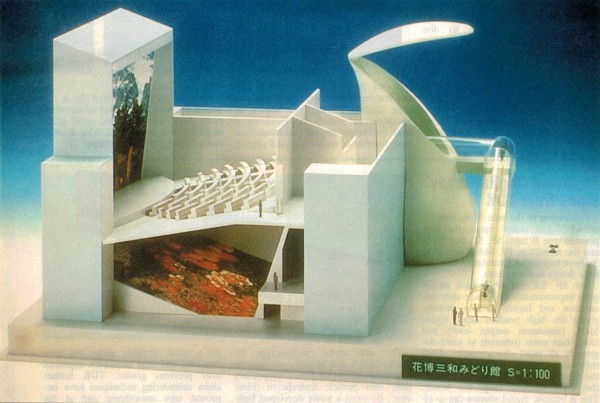

A model of the Sanwa Midori-Kan pavilion at Expo ’90 in Osaka, Japan, which housed the IMAX Magic Carpet Theater.

Expo ’90 brochure. Courtesy of Charles Konowal.

Interior view of the Magic Carpet theater at Futuroscope in France, 2012. The floor panels in front of the seats and the slanted panels behind the seats are transparent to allow viewing of the lower screen.

Photo by James Hyder / © 2012 by Cinergetics, LLC.

The crew of Voyageurs du ciel et de la mer (2004) filming a royal eagle in the Alps. Note that the 15/65 camera is mounted vertically.

Courtesy of Galatée Films.

Selected Filmography

Technology

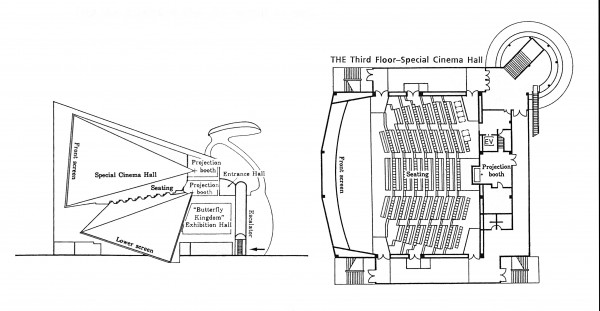

Magic Carpet consisted of a full-size IMAX screen in front of the audience, and a second beneath its feet, visible through transparent floor panels and slanted portals under the seats.

Two strips of 15/70 film were projected by two electronically synchronized IMAX projectors with water-cooled 15kW xenon lamps from two projection booths above and behind the auditorium. Both strips ran through continuous loop cabinets in the upper booth to eliminate the need for rewinding and rethreading, permitting quick turnaround of the theater between shows. The lower projector was angled 45 degrees downwards to project directly onto the screen below the audience (Wales, 2022).

In Osaka, six-channel analog audio was played back from an Otari half-inch, eight-track tape deck to speaker arrays in six positions. Channels 1–5 went to the normal IMAX theater positions: screen left; center; right; house rear left; and rear right. But unlike all other IMAX installations, Channel 6 was not assigned to the screen top position, but to the lower screen. Since sound would not pass through the floor panels, this was achieved with speakers under the seats that reflected sound off the angled glass portals. A sub-bass array, whose signal was derived from the six main channels, was located behind the upper screen.

For the permanent Magic Carpet theater at Futuroscope, six channels of uncompressed digital audio were played back from a Sonics DDP unit, which used three compact discs. The seat-mounted lower-screen speakers were also improved.

To allow for a good view of the lower screen, the seats were farther apart and much less steeply raked than in a standard IMAX theater. This significantly reduced seating capacity. For instance, the upper screen in the Magic Carpet theater at Futuroscope was 22.3 x 31.5m (73.1 x 103.3 ft), the fourth largest in the world while it was in operation, but the house seated only 246 people. In comparison, some theme-park IMAX theaters with smaller screens seated nearly 1,000, and the average capacity for IMAX theaters of the time was between 400 and 500.

A model of the IMAX Magic Carpet theatre at Osaka Expo ’90. The projection box is on the right and the two screens on the left: one is a vertical position and the other beneath a clear plastic floor.

Smith, Barrie (1991). “A Magic Carpet – and 3D with LCD's”. Electronics Australia (January): p. 12.

Sanwa Midori-Kan pavilion at Expo ’90 in Osaka, Japan, which housed the IMAX Magic Carpet Theater.

Expo ’90 brochure. Courtesy of Charles Konowal.

References

Ferguson, Graeme (2016). “Remembering Colin Low”. LF Examiner, April 2016.

Hyder, James (2004). “LFCA Coverage Cont’d”. LF Examiner, Summer 2004.

IMAX Corporation (1992). “International Directory of Theatres with IMAX® or OMNIMAX® Motion Picture Projection Systems”, May 1992.

Konowal, Charles (2022). Unpublished interview with James Hyder, December 5, 2022.

Wales, Alvis (2022). Unpublished e-mail correspondence with James Hyder, December 27–28, 2022.

Patents

None.

Preceded by

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

James Hyder worked at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, from 1984 to 1996, where he managed the world's most popular IMAX theater and assisted in the development and production of sveral IMAX films for the museum. In 1997, he founded MaxImage!, the first independent publication dedicated exclusively to the giant-screen industry, renamed LF Examiner in 2000. He was the newsletter's writer, photographer, designer, editor, and publisher for 24 years until its closing, and his retirement, in 2021.

The following individuals provided essential assistance for this article:

Leo Baljet, IMAX Corporation

Gordon Harris, ex-IMAX Corporation

Charles Konowal, producer

Stephen Low, director

Dominque Prisset, Futuroscope

Alvis Wales, ex-IMAX Corporation

Hyder, James (2024). “IMAX Magic Carpet”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.