A nine-screen film installation of 35mm film projections in a 360-degree circular format.

Film Explorer

Magie des rails (1964), shot in the Swiss Alps. Circle-Vision 360º used a custom camera rig to photograph a 360-degree wraparound image onto nine strips of 35mm film. The twelve-channel audio was contained on two separate reels of magnetic film.

Cinémathèque suisse, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Identification

23.01mm x 18.67mm (0.906 in x 0.735 in).

Each of the nine screens was in approximately 4:3 aspect ratio; full-circumference panoramic view was 11.87:1.

Eastman Print Stock.

Single edge tinted near-black; overtop black edge, “Eastman”, “Safety Film” and Eastman Kodak date code for USA-produced film stock printed in black.

9

Film was shot in Eastman color negative, but prints were processed by Technicolor, in a special arrangement held with Walt Disney Productions. High-precision color control was necessary in processing the film prints – any discrepancy in color, between reels, would be noticeable when all nine screens were juxtaposed.

Walt Disney’s Circle-Vision 360º

Two six-channel 35mm magnetic soundtracks were synchronized with the nine reels of picture film. The audio tracks were moved to separate sound reels to maximize the space available for the image.

24.89mm x 18.67mm (0.980 in x 0.735 in).

Eastman color negative.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

History

Circle-Vision 360° is a film technique invented by Ub Iwerks for Walt Disney Studios using nine synchronized 35mm cameras, arranged in a circle to capture a 360-degreee view; subsequently projected onto nine elevated screens, to create a full 360-degree panoramic effect. Upgrading Disney’s innovative Circarama format (16mm film; 11 screens) of the 1958 film, America the Beautiful, featured at Tomorrowland (Disneyland, Anaheim, CA), Circle-Vision 360° increased the earlier format’s image quality, with larger 35mm film, and heightened its immersive effect, by reducing the spatial distortion between screens. (Some Circarama films, such as Italia 61 [1961], as shown at the Torino international labor exhibition, were filmed in 16mm and blown up to a 35mm format.)

The first film created for the new 35mm format, Magie des rails (1964), was scripted, directed and produced by Ernst A. Heiniger (who had previously made films for Disney in the 1950s), for Expo 64 in Lausanne, Switzerland. The 360-degree film was of a railroad journey through Switzerland and its Alps – with additional scenes shot in Paris (France), Pisa (Italy) and Vienna (Austria) – initiating the “travelogue” genre that would characterize subsequent Circle-Vision 360° films. It has been described as, “a four-movement ‘symphonic poem’ … consisting of 64 sequences and structured by the four seasons and the four elements of earth, water, fire and air” (Schärer, 2014: p. 16). In 1965, Canada 67 was commissioned by the Telephone Association of Canada for Montreal’s world exhibition Expo 67. The film was co-produced by Disney and Robert Lawrence Productions in Toronto, and was directed by Robert Barclay and cinematographer Fritz Spiess, both seasoned Canadian filmmakers. As seen in production stills, the production’s $250,000 camera rig was a large, heavy and awkward contraption that had to be transported by plane, boat, and a variety of land carriers, to shoot the film’s 80 scenes capturing Canada’s magnificent, coast-to-coast landscapes. Canada 67 screened alongside numerous expanded multiscreen experiments in other Expo 67 pavilions, including Labyrinth (directed by Colin Low and Roman Kroitor of the National Film Board of Canada) and Polar Life (directed by Graeme Ferguson), both films considered precursors to what would become IMAX; as well as We are Young (directed by Francis Thompson and Alexander Hammid). Like the earlier Expo 64 film, Circle-Vision 360° technology made Canada 67 and the Telephone Pavilion among the most visited at Expo 67. In the same year, America the Beautiful was remade in 35mm for Tomorrowland at Disneyland, Anaheim, CA.

The first Circle-Vision 360° film installations were presented with nine projectors, each covering a 40-degree arc of the circular screen, capable of creating the illusion of a single 360-degree image with a single horizon line – critical facets of the film’s presentation and reality effect. Up to 1,500 viewers entered the theater and stood freely, inside rails at the center of the auditorium, encircled by screens and speakers. As the viewers’ gazes moved freely, each spectator was essentially creating their own film. As one commentator quipped: “Depending on the range of your peripheral vision, you missed at any moment a quarter to a half of the film; it seemed to be made for people with eyes in the backs of their heads” (Fulford, 1968: p. 90). The visceral immersive experience of the wraparound cinematic panorama made for thrilling sensory viewing and directors maximized the effect with the inspired transport of their Circle-Vision 360° cameras, “moving” audiences swiftly over land and water – with aerial views that created a dramatic, embodied sensation of “being-there” within the expansive landscapes. In later films, such as Impressions de France (1982) and Wonders of China (1982), the single 360-degree image was often broken up, with different sections of the nine-screen composite showing separate images – this technique continued to be used in later Circle-Vision 360° films.

The unique and demanding technical requirements of Circle-Vision 360° production and projection, ensure that most of the films have exclusively screened as attractions inside Disney theme parks. Following presentations at national and world exhibitions in 1964, 1967 and 1986, Circle-Vision 360° film technology has been used for eight additional films from Walt Disney Productions– all housed in the unique theaters and architectures required, in Disney theme parks located in the US, France and Japan. Six of these films were directed by Jeff Blyth who vividly describes the experience of directing Wonders of China (1982) in his 2021 book Polishing the Dragons (Blyth, 2021).

Canada 67 (1967), winter scene (with audience), at Expo 67, Montreal, Canada. Photograph by Ruggles.

Bell Historical Collection 29726-15, Bell Archives, Montreal, Canada.

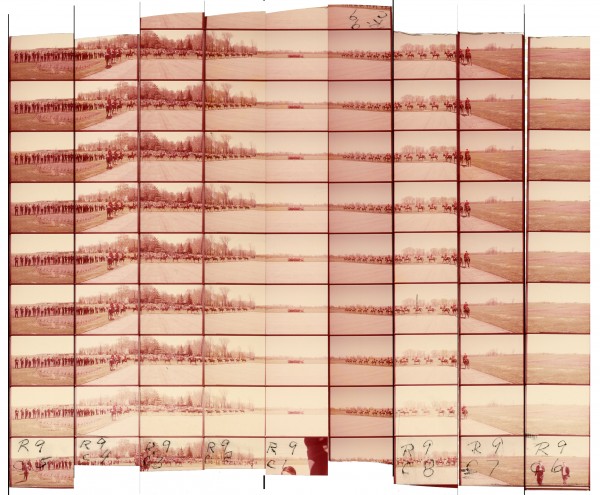

Sample reconstruction from Canada 67 (1967). These variably faded strips of 35mm, from original prints, have been aligned and digitally recombined to illustrate a sense of the full scope of the 360-degree wraparound image.

Courtesy of Lorraine Spiess,Toronto, ON, Canada.

Selected Filmography

Opened at Tomorrowland in Disneyland, California, and Walt Disney World, Florida, where it screened until 1994; also screened at Tokyo Disneyland between 1986 and 1992. Approx. 19 mins.

Opened at Tomorrowland in Disneyland, California, and Walt Disney World, Florida, where it screened until 1994; also screened at Tokyo Disneyland between 1986 and 1992. Approx. 19 mins.

Created and screened at the Telephone Pavilion at Montreal’s world exhibition Expo 67. Original film elements are held at Walt Disney Studio Archives. 22 mins.

Created and screened at the Telephone Pavilion at Montreal’s world exhibition Expo 67. Original film elements are held at Walt Disney Studio Archives. 22 mins.

Replaced O’Canada in the Canada Pavilion at EPCOT Centre, Florida, Narrated by actors Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara. Filmed on 35mm, but projected digitally. 12 mins.

Replaced O’Canada in the Canada Pavilion at EPCOT Centre, Florida, Narrated by actors Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara. Filmed on 35mm, but projected digitally. 12 mins.

Created in Switzerland for the Autostadt theme park near Wolfsburg. 20 mins.

Created in Switzerland for the Autostadt theme park near Wolfsburg. 20 mins.

Created for EuroDisneyland (later Disneyland Paris) and subsequently, in an edited form renamed The Timekeeper, for the Magic Kingdom, Florida, and Tokyo Disneyland from 1994 to 2006. 18 mins.

Created for EuroDisneyland (later Disneyland Paris) and subsequently, in an edited form renamed The Timekeeper, for the Magic Kingdom, Florida, and Tokyo Disneyland from 1994 to 2006. 18 mins.

Created for, and screened during, the world exhibition Expo 64 at Lausanne, Switzerland (April 30–October 25, 1964), and later, in summer/autumn 1965, at the Internationale Verkehrsausstellung [International Transportation Fair], Munich, Germany. The nine reels of film were digitized and recombined in 2014. Approx. 20 mins.

Created for, and screened during, the world exhibition Expo 64 at Lausanne, Switzerland (April 30–October 25, 1964), and later, in summer/autumn 1965, at the Internationale Verkehrsausstellung [International Transportation Fair], Munich, Germany. The nine reels of film were digitized and recombined in 2014. Approx. 20 mins.

Created for the Canada Pavilion at EPCOT Centre, Florida, where it screened from 1982 up to 2019 – replaced by Canada Far and Wide in 2020. 18 mins.

Created for the Canada Pavilion at EPCOT Centre, Florida, where it screened from 1982 up to 2019 – replaced by Canada Far and Wide in 2020. 18 mins.

Created for the Telecom Canada Pavilion at the world exhibition Expo 86 in Vancouver, Canada. Approx. 21 mins.

Created for the Telecom Canada Pavilion at the world exhibition Expo 86 in Vancouver, Canada. Approx. 21 mins.

Replaced Wonders of China in the China Pavilion at EPCOT Centre at Walt Disney World, Florida. Screened through to 2003. 14 mins.

Replaced Wonders of China in the China Pavilion at EPCOT Centre at Walt Disney World, Florida. Screened through to 2003. 14 mins.

Created for the China Pavilion at EPCOT Centre at Walt Disney World, Florida. Screened through to 2003, when it was replaced by Reflections of China. Approx. 19 mins.

Created for the China Pavilion at EPCOT Centre at Walt Disney World, Florida. Screened through to 2003, when it was replaced by Reflections of China. Approx. 19 mins.

Technology

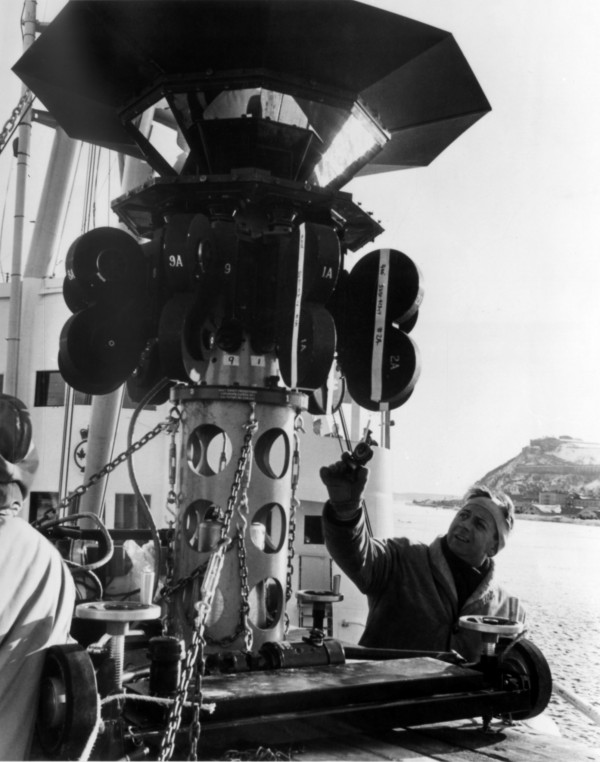

Like other panoramic film technologies, Circle-Vision 360º is notable for its comprehensive field of view – only made possible by unique camera rigs and projection set-ups. The camera rig, developed over several iterations from the earlier 16mm Circarama camera assembly, consisted of nine custom-modified Mitchell 35mm GC cameras, mounted radially around a central column, pointed upwards towards a circular array of mirrors (Iwerks, 2019). Shooting via a tight, mirrored array reduced dead-spots between the individual camera fields of view that would arise if the cameras were arranged pointing horizontally outward around a central point. Cameras were synchronized by mechanical coupling, via a common geared shaft, to a single 24V DC motor mounted inside the column, which could be adjusted to run at speeds anywhere between 6 fps to 36 fps (American Cinematographer, 1967: p. 569). The common gear ensured that every film movement, in every camera, rotated in synchrony, resulting in precisely the same number of frames exposed for every shot. The fully assembled camera rig was approximately 3-ft (0.91m) tall and weighed about 300–350 lb (136–158.8kg).

Subsequent projection of the nine concurrent strips of film was achieved by positioning nine projectors in small gaps between the nine screens, projecting diametrically across the theater. These projectors consisted of 35mm Simplex heads and 2,500w lamp houses and were, much like the synchronized camera assembly, mechanically connected to each other. Audio playback was via a custom 220V, three-phase interlock system (American Cinematographer, 1967: p. 569). Screens for Canada 67 measured 23 ft (7.01m) high and had a 273-ft (83.21m) circumference. In the Canada 67 projection room, a lead projectionist was supported by three additional projectionists, each in charge of three projectors. Subsequent advancements and innovations in the projection technology eventually led to the need for no live projectionists. The development of continuous-loop cabinets meant no rewinding of film, no rethreading of the projectors – at the end of the show, the system automatically returned to the start-point for the next presentation. Virtually all of the Circle-Vision 360º presentations in the theme parks used this technology until recently, when projectors were converted to digital.

One particular feature of the early camera assembly was that, despite its bulk and relative complexity, it was designed for mounting on a variety of vehicles, including not only land-based vehicles, but also air- and water-craft. For instance, during the filming of Canada 67, the most technically impressive of these mountings was used for aerial photography.

Various techniques were devised to overcome the unique physical restrictions presented by the camera assembly. Early in the development of Circle-Vision 360º, a rig with an indexing plate and a single camera was used for filming panoramas where there was minimal movement, and stable lighting conditions, but restricted space. The camera would shoot a length of film, before being rotated to the next angular position, simulating the full bank of nine cameras (Iwerks, 2019). The restrictions of physical space within the rigs had an impact on the maximum length of each shot, when the desire for longer continuous scenes in later films necessitated larger film magazines. Newer 1,000-ft (304.8m) magazines (unlike the earlier 400-ft [121.92m] magazines) would encroach into shot, so their profiles were redesigned to remain out of frame. In later iterations, motorized lens adjustment was added, enabling control of both exposure and zoom in the nine cameras without the need to remove them one-by-one from the mirror assembly. Disney now uses an all-digital Circle-Vision rig, consisting of seven RED cameras, with output blended in post-production into a seamless 360-degree presentation.

Cinematographer Fritz Spiess with nine-camera Circle-Vision 360º rig, Halifax, Canada, 1966, during the filming of Canada 67 (1967).

Bell Historical Collection 37737, Bell Archives, Montreal, Canada.

Lead Projectionist Ben Spielvogel checking sound playback machines, Canada 67 projection room, 1967. In addition to the lead projectionist, three additional projectionists overlooked three projectors a piece. Photograph by Ruggles.

Bell Historical Collection 29742, Bell Archives, Montreal, Canada.

Three inter-locked KEM flatbed editing machines used in making Circle-Vision 360º films. This arrangement used nine images synchronized with three 35mm magnetic sound tracks.

Courtesy of Jeff Blyth.

References

American Cinematographer (1967). “Circle-Vision 360”. American Cinematographer, 48:8 (August): pp. 568–9.

Association of National Advertisers Audiovisual Committee (1968). Pioneering Audiovisual Techniques. New York: Association of National Advertisers.

Barclay, Robert (2014). “Making Disney’s Canada 67”. In Reimagining Cinema: Film at Expo 67, Monika Kin Gagnon & Janine Marchessault (eds), pp. 234–40. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP.

Bell Archives, Montreal, Canada.

Blyth, Jeff (2021). Polishing the Dragons: The Making of EPCOT’s Wonders of China. Bamboo Forest Press.

Fritz Spiess Fonds, Toronto, Canada http://mediacommons.library.utoronto.ca/fonds/spiess-fritz

Fulford, Robert (1968). This was Expo! Toronto: Canadian Illustrated Library.

Gagnon, Monika Kin (2014). “All-embracing Circle-Vision 360º: Canada 67 at Expo 67’s Telephone Pavilion”. In Reimagining Cinema: Film at Expo 67, Monika Kin Gagnon & Janine Marchessault (eds), pp. 218–33. Montreal: McGill-Queen's UP.

Iwerks, Don (2019). Walt Disney’s Ultimate Inventor: The Genius of Ub Iwerks. Glendale, CA: Disney Publishing Group.

Michaux, Emmanuelle (1999). Du panorama picturale au cinéma circulaire. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Schärer, Thomas (2014). “Das Circarama-abenteur der Scweizerischen bundesbahnen [The Circarama Adventure of the Swiss Federal Railway]”. MemoriaV Bulletin, 21 (September): pp. 16–17. https://memoriav.ch/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Bulletin-21_Web.pdf

Spiess, Lorraine (2014). “Introduction to the Panoramic Reconstruction of Canada 67”. In Reimagining Cinema: Film at Expo 67, Monika Kin Gagnon & Janine Marchessault (eds), pp. 246–53. Montreal: McGill-Queen's UP.

Witte, Gerhard (n.d.). “Circarama at Expo in Lausanne Switzerland”. www.in70mm.com. https://www.in70mm.com/presents/1963_circarama/expo/index.htm (accessed November 17, 2024).

Patents

Walter E. Disney and Ub Iwerks, for a “panoramic motion picture presentation arrangement”. US Patent 2,942,516, filed July 17, 1956, and issued June 28, 1960 (contained within patent related to Circarama).

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Monika Kin Gagnon is professor of Communication Studies at Concordia University, Montreal, Canada. She is author, editor and co-editor of numerous essays and books, including Reimagining Cinema: Film at Expo 67 (2014), co-edited with Janine Marchessault; and In Search of Expo 67 (2021) based on a 2017 exhibition of 22 artists co-curated with Lesley Johnstone, which included a programmed section of restored and simulated expanded cinema from Expo 67. She is currently a member of the research group, Locating Transnational Collaborations in the Early History of Imax Films and Architectures (1970–1990).

Chip Limeburner is a doctoral student at Concordia University, Montreal, Canada, where their research turns on questions of tech integration in themed entertainment. While their dissertation work is focused on nighttime spectaculars, through membership to both the Technoculture, Arts, and Games (TAG) Lab, and the Centre for Sensory Studies, they are also engaged with design research on interactive embedded tech, multisensory cinema and stuntronics. A scenic designer and creative technologist by professional experience, they not only maintain ties to the Themed Experience and Attractions Academic Society (TEAAS), but also the Themed Entertainment Association (TEA) and International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions (IAAPA) as well.

Many thanks to Jeff Blyth, interview (via Zoom) with Monika Gagnon and Chip Limeburner, January 16, 2024.

Gagnon, Monika Kin & Chip Limeburner (2025). “Circle-Vision 360º”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.