A variation of Disney’s nine-camera Circle-Vision 360 system, in which only five cameras and projectors were used to create a 200-degree widescreen image viewed on a curved screen by audiences seated in a theater.

Film Explorer

Circle-Vision 200 created an extra-wide 200-degree curved image by projecting five strips of 35mm film in synchronization.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

Identification

23.01mm x 18.67mm (0.906 in x 0.735 in).

Five-screens wide by one-screen high.

Eastman print stock.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings.

5

Accurate screen-to-screen color was required as the slightest variations in tint or density were immediately apparent since the five screens were side-by-side and contiguous. All original camera negative rolls came from the same emulsion batch of Kodak film. A few shots in low-light conditions required 8518 Fujicolor A250T. Technicolor maintained consistent and rigorous laboratory standards, such as ensuring all matching camera rolls were developed in fresh chemicals, and all at the same time. In the theater, projector light sources needed to have matching illumination levels and color temperature.

None

Unlike earlier Circle-Vision 360 and Circarama productions, starting with Disney’s EPCOT theme park in 1982, the soundtracks for multi-screen attractions matched the imagery, utilizing the individual speakers behind each screen as well as sub-woofer and overhead-speaker arrays as discrete channels. For post-production this necessitated a circular mixing stage incorporating hundreds of channels synchronized to five video displays in order to have specific sounds or dialogue follow the action precisely from screen to screen. A typical 18-minute film required six weeks of pre-mixes and then a final mix-down.

24.89mm x 18.67mm (0.980 in x 0.735 in).

Eastman color negative, or Fuji color negative.

Standard Eastman Kodak, or Fuji edge markings.

History

Disney’s experimentation with 360-degree film experiences date back to before the advent of the original Disneyland (see Circarama). All of the system’s variations incorporate an array of film cameras pointed outward from a central hub to capture in-the-round cinema, which is then projected from a ring arrangement of film projectors. Audiences stand in the middle of the circular theater with the freedom to look in any direction at the surrounding images. When Disney’s EPCOT Center opened in October 1982 in Orlando, Florida, the World Showcase featured three pavilions with new Circle-Vision presentations: two films made on location in China and Canada in full 360-degrees (see Circle-Vision 360), and a third film about France with a 200-degree field of view. The concept for a 200-degree five-screen presentation was the inspiration of filmmaker Rick Harper who wrote, directed and was the cinematographer for Impressions de France (1982). Harper felt guests needed an opportunity to sit comfortably in a theater to fully appreciate the French culture and scenery on display, unlike the Circle-Vision 360 format where the audience had to stand to enjoy the fully-immersive experience.

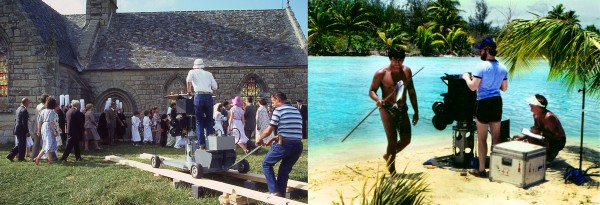

Because it was less expensive to shoot with five cameras rather than Circle-Vision 360’s nine, Harper’s idea quickly received approval from Marty Sklar and Randy Bright of Walt Disney Imagineering, and Bob Gibeaut and Ron Miller of Disney Studios. The new system also opened up opportunities for the filmmaker to avoid one of the central difficulties of filming in full Circle-Vision. Instead of having to remove all equipment boxes and extraneous personnel out of a shot – normally a very time-consuming process – filming in 200-degrees made it easier to clear the scene of unwanted items and to bring lighting equipment in close where it might otherwise be seen on film. Additionally, this system offered what does not exist in Circle-Vision 360: a limited theatrical proscenium that framed the scene. In effect, entrances and exits could be made “stage left”, or “stage right,” as in a play. Dolly shots were simplified, even cranes could be used, and, perhaps significantly for directors, there was no crawling on hands and knees to stay out of the shot while trying to monitor what was happening in every direction. Being able to simply stand behind the camera to observe the entire scene was liberating for both the director and crew.

Opportunities expanded even further for the second Circle-Vision 200 production, this time for Tokyo Disneyland, in 1983. Filmed in the air, on land and underwater, The Eternal Sea pushed the format by adding professional actors playing historical roles in ways that would have been difficult without a theatrical-style proscenium that allowed for entrances and exits. The limited scope of the panoramic shot also allowed more precise and dramatic photography because lighting equipment could be brought in as close as necessary and positioned just out of shot. The 200-degree process even affected the editing of both productions because the director could control where the audience was looking from shot to shot. The Eternal Sea filmed with two units in locations as varied as the Greek islands, Venice, Japan, Australia, Truk Lagoon, Micronesia, (now known as Chuuk), the Bahamas, and Bora Bora, French Polynesia.

Randy Bright, who supervised the many EPCOT film productions, wanted to include an outtake from Impressions de France in a 360-degree Tokyo Disneyland attraction called Magic Carpet Around the World. Because all the French footage had originally been shot with five cameras, there were no outtakes available in the studio library of stored and unused materials. Rick Harper had to refilm an aerial scene of a French chateau, this time with nine cameras. To avoid a similar situation on The Eternal Sea, which was to be shot on far-flung locations around the world, Bright’s directive was to film whenever possible with all nine cameras, and select the final five images in post-production. All underwater shots and aerials, in addition to a few ground-based scenes, were filmed with all nine cameras so as to make any outtakes more useful to the studio library.

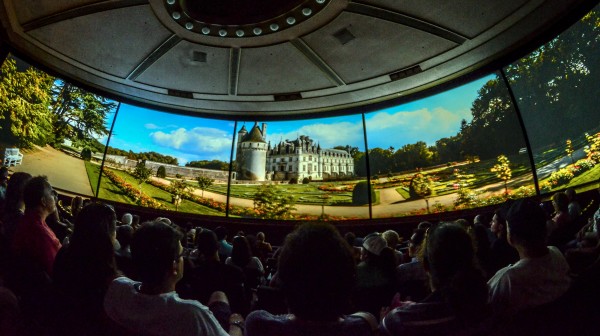

Audience seated for Circle-Vision 200 theater presentation of Impressions de France (1982) at EPCOT Center in Orlando, Florida.

Disney Studios.

Filming a flower market for Impressions de France (1982) in Circle-Vision 200 (below) and the finished presentation (top) – here seen on three of the five screens.

Top: Disney Studios; bottom: by the director’s wife, Ann Harper.

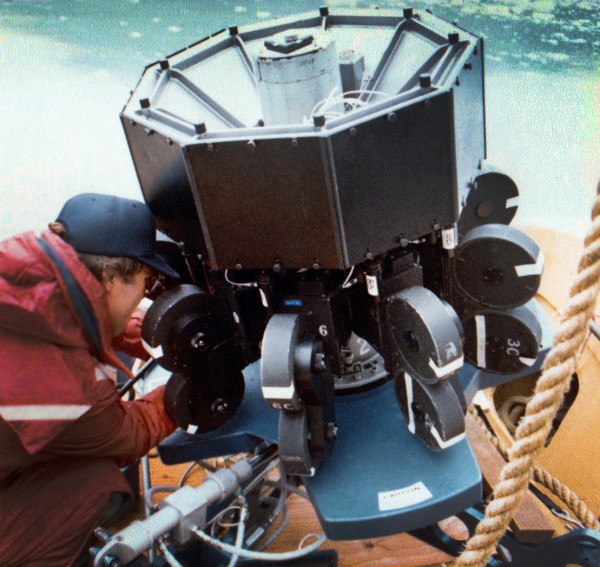

Left: Director Rick Harper behind the Circle-Vision 200 camera on location for Impressions de France (1982); right: Director Jeff Blyth stands behind the camera on location in Tahiti for The Eternal Sea (1983).

Left: Photo by the director’s wife, Ann Harper; right: photo by script supervisor Susan Stribling.

Filming The Eternal Sea (1983) in Circle-Vision 200 on board the sailing ship Marques in the English Channel, with actors portraying the British Royal Navy c. 1790.

Photographs by the director, Jeff Blyth.

Selected Filmography

Made for Tokyo Disneyland, Tokyo, Japan.

Made for Tokyo Disneyland, Tokyo, Japan.

Made for EPCOT Center World Showcase, Orlando, FL, United States.

Made for EPCOT Center World Showcase, Orlando, FL, United States.

Technology

From a physical standpoint, the main difference between shooting Circle-Vision 200 and Circle-Vision 360 was mounting only five cameras on the central pedestal, instead of nine. All of the support equipment remained the same, but physical production was expedited because the narrower field of view created a 160-degrees space to the rear that could be used to hide personnel and keep technical equipment close at hand. This also facilitated using specially built camera rigs designed for the limited view, in addition to cranes and dollies that typically would be visible in the back cameras of Circle-Vision 360.

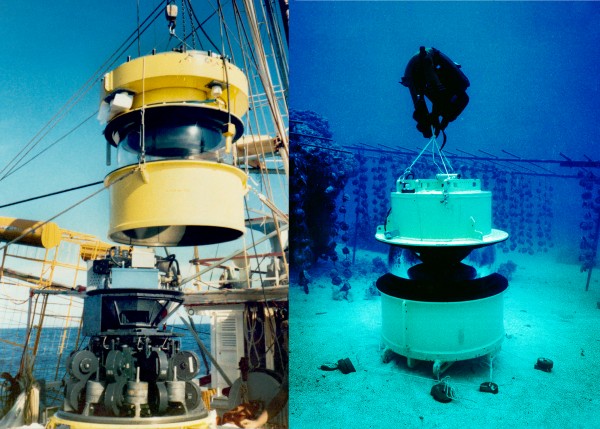

The enormous underwater housing that had been created for photography on The Eternal Sea required ballast to maintain an even weight distribution. Despite being a five-camera production, nine cameras had to be loaded in the rig at all times underwater, even if this meant the back screens might be obscured or otherwise unusable. The bulk and weight of the water-tight housing necessitated using a huge crane on a barge to lower the unit into the water. The same underwater rig was also used in a salmon stream for Portraits of Canada (1986), with a submersible at a shipwreck in the Bahamas for From Time to Time (aka The Timekeeper) (1992), and in the Florida Keys for American Journeys (1984), all Circle-Vision 360 productions.

Aerial photography for both Circle-Vision 200 productions utilized Aérospatiale Lama helicopters for their high-lift capability. Unfortunately, none of these helicopters, not even a lesser-powered Bell Jet Ranger, were available anywhere in the South Pacific. Instead, a twin-engine North American Mitchell B-25 bomber was transported by its flight crew from Vancouver, Canada, island-hopping all the way to Tahiti. A specialized mechanical arm, which had been used for aerial photography on Canada 67 for the Montreal EXPO in 1967, swung the Circle-Vision cameras down and out of the bomb bay far enough below the WWII-era aircraft that the airframe was not visible during photography.

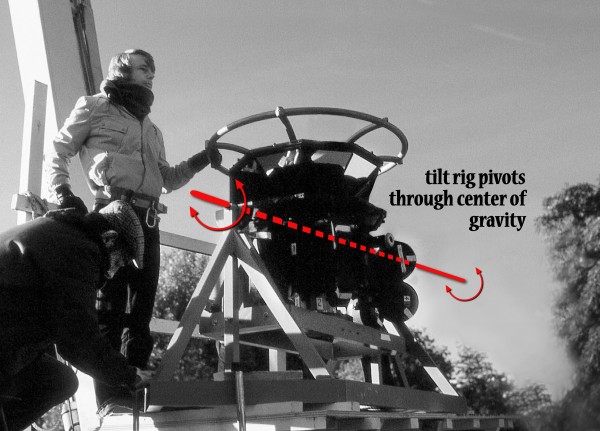

Another device created specifically for The Eternal Sea production was an actuator-driven stabilizer system for filming on the sea. The one-of-a-kind unit was built by Nelson Tyler who had achieved great fame as a designer of helicopter camera mounts. The Circle-Vision camera rig (again requiring the symmetrical balancing of all nine cameras) could remain perfectly level, even when filming in 15-ft (4.57m) seas in the English Channel – a must to avoid seasickness effecting audiences. A gasoline-driven generator powered a hydraulic pump that actuated the mount’s stabilizers, making for a noisy and cumbersome set-up – but the results were worth the extra effort. The same stabilization unit was later used on American Journeys (1984) for a shot from a small Coast Guard vessel, weaving among glaciers in Alaska.

Don Iwerks and the Disney Studio Machine Shop also designed and built a tilt-plate rig at the request of Rick Harper for Impressions de France. The specialized device rotated around a pivot point that coincided with the unit’s center of gravity, which meant it could smoothly tilt up or down without much physical effort. While initially fabricated for two specific 200-degree shots (one of the Eiffel Tower, Paris, and another of Mont Saint-Michel, Normandy), the same rig was later used on 360-degree productions like Wonders of China (1982), American Journeys (1984), and Portraits of Canada (1986). Unlike on the five-camera Impressions de France, these productions had to consider what would be appropriate imagery for the back panels because, as the front cameras tilted up, the rear cameras tilted down.

A five-camera base plate built earlier for the Disney Hall of Presidents theme park attraction at Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida, was also utilized for shots on both Circle-Vision 200 productions. Telephoto images could be captured with 135mm lenses after each individual camera was aligned horizontally. But this flat-base arrangement of the cameras harkened back to the very early days of the original Circarama set-up, with that system’s flaws of overlaps and blind spots. Filming scenes of the ocean from the shore helped minimize this effect because variation in waves did not appear as discontinuities between screens. For The Eternal Sea, a scene filmed on Bondi Beach in Sydney, Australia, required keeping five windsurfers within the confines of their individual frame, not easy to do when fighting natural variables. Had the surfers crossed over from one frame to the next, the illusion of a continuous image would have been broken as they would have either disappeared briefly, or been doubled up. Another five-screen scene on that production was filmed on a tiny South Pacific atoll accessible only by small plane. A single Arriflex camera was set up on a tripod so that the camera could be aligned with the distant horizon. Each of the five locked-off images was shot separately, with careful repositioning of the camera between takes, to create the impression of a full five-camera shot.

Within the hectic confines of a Disney theme park, there were precious few places where guests could enjoy the comfort of a theatrical presentation while seated. Both Impressions de France and The Eternal Sea played to audiences in air-conditioned theaters, each with a maximum capacity of approximately 260 guests per show. The screens were deeply curved and separated by thin, black vertical strips, called mullions, in order to mask the very slight overlap of imagery between adjacent screens. These theatrical presentations benefited from four advantages over their cousins, the full Circle-Vision 360 shows:

• viewers had no need to crane their necks or physically turn around to see images playing behind them;

• in 360-degree presentations, there is a distracting projector light for the opposite screen emanating from each mullion – in this case the five projectors were located in a booth behind the audience;

• there was no spillover reflection of projector light from back screen imagery that tended to wash-out the screens in front;

• and perhaps most importantly, a 200-degree theater did not suffer from the conflicting sounds that echo back and forth in a geometrically circular theater, so Circle-Vision 200 soundtracks were acoustically superior.

mpressions de France (1982). Director Rick Harper films the Fountain of Apollo at Versailles, France, in 200-degrees from a low angle. If this camera set-up had been attempted in Circle-Vision 360, Harper and his crew would have been “in the shot”.

Photograph by the director’s wife, Ann Harper.

Left: Assembly of the Disney custom-built housing for Circle-Vision underwater filming – note the added weights between cameras; right: on location at a pearl farm in Tahiti for The Eternal Sea (1983).

Left: Photograph by Daryll Davis, camera technician; right: photograph by Al Giddings, second unit director.

Behind-the-scenes on The Eternal Sea (1983). The Nelson Tyler-designed, hydraulically-stabilized rig for Circle-Vision cameras, to minimize motion-sickness inducing movement when filming on open water.

Photograph by the director, Jeff Blyth.

Director-Cinematographer Rick Harper films a tilt-shot on location in France with a specially-made device created by Don Iwerks and the Disney Studio Machine Shop.

Photograph by the director’s wife, Ann Harper.

Filming with the base-plate rig on location in Tahiti, Polynesia, for The Eternal Sea (1983). Camera technician Garry Broggie carefully aligns the five Circle-Vision cameras with telephoto lenses to minimize overlaps and void areas when not using the pedestal mount. Plastic translucent slates were filmed at the start of the roll to identify each camera.

Photograph by the director, Jeff Blyth.

References

Iwerks, Don (2019). Walt Disney’s Ultimate Inventor, the Genius of Ub Iwerks, pp. 148–9. Glendale, CA: Disney Publishing Group.

Iwerks, Don (2023). Personal interview with Jeff Blyth (and Garry Broggie) (September 6, 2023). Ojai, CA, United States.

Harper, Rick (2023). Correspondence, conversations and emails with Jeff Blyth (November 2023).

Patents

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Jeff Blyth is a filmmaker who has made several Circle-Vision 360 films for Walt Disney Imagineering, including Wonders of China (1982) and Reflections of China (2003) for EPCOT, American Journeys (1984) for Disneyland and Walt Disney World (Writer and Co-Director with Rick Harper), Portraits of Canada for EXPO 86, and From Time to Time (aka Timekeeper) for Disneyland Paris and Walt Disney World (1992). He also wrote, produced, and directed the Circle-Vision 200 premiere attraction The Eternal Sea for Tokyo Disneyland (1983). He has authored the book Polishing the Dragons: The Making of EPCOT’s Wonders of China, published by Bamboo Forest Press, 2021. In addition, he has written and directed Light & Life (1991), an IMAX film for the centennial of Philips Lighting, Netherlands and worked as a producer/cameraman on the IMAX films, Behold Hawai’i (1983) and To Fly (1976). He directed the feature film Cheetah for Walt Disney Productions (1988), shot entirely on location in Kenya. He is a member of the Writer’s Guild of America, the Director’s Guild of America, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Documentary Branch.

Rick Harper, Don Iwerks, Garry Broggie.

Blyth, Jeff (2024). “Circle-Vision 200”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.