A camera and projector system that created 360-degree films for presentation in a circular theater. The audience stood surrounded by overhead screens, initially eleven in number, then later nine. The earliest version was projected in 16mm while moves were made to blow-up the material to 35mm mm for future release prints.

Film Explorer

Circarama projected eleven Technicolor dye-transfer 16mm prints in synchronization in a specially-constructed auditorium to create a 360-degree wraparound image.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

Circarama productions were photographed on eleven strips of 16mm Kodachrome film in synchronization using a custom camera rig.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

Identification

9.65mm x 7.21mm (0.38 in x 0.28 in) x 11 (for initial 16mm presentations; 23.65mm x 17.73mm (0.93 in x 0.70 in) x 9 (for later full-aperture 35mm presentations.

15:1 (11 screens); 12:1 (9 screens)

1-perforation, vertical (16mm, 1955-1957); 4-perforation, vertical (35mm, from 1957).

Technicolor IB prints.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge coding.

11 for original version, then later 9.

Accurate screen-to-screen color was required because the slightest variations in tint or density were immediately apparent since screens were viewed side by side. For A Tour of the West Commercial Kodachrome stock was used for photography, while Kodak Ektachrome was used on Italia 61. To ensure consistent color, all camera stocks came from the same Kodak production batch to minimize even the slightest manufacturing variables. Technicolor, which had a long-term contract with Disney, set up and maintained precise standards for 360-degree filming, such as ensuring all matching camera rolls were developed in fresh chemicals simultaneously. This also applied to same-batch print stock. Disney had pioneered optical blow-ups from 16mm low-contrast Kodachrome to 35mm Technicolor imbibition (IB) dye-transfer prints on their “True Life Adventure” series and used the same procedures for all Circarama prints. In the theater, projector light sources needed to have matching illumination levels and color temperature.

By Circarama; In Circarama

Walt Disney’s personal working philosophy was that guests should have the exact same experience each time they viewed the film, regardless of where they stood within the theater. He insisted on a monaural soundtrack that was fed equally out of each screen speaker. The sound was played back on a four-head 35mm full-coat magnetic track on a Kinevox sound reproducer, synchronized with the projectors via General Electric Selsyn motors.

(extra channels carried the same monaural track as back-up)

10.27mm x 7.49mm (0.40 in x 0.29 in).

Commercial Kodachrome initially, Kodak Ektachrome, then Eastman Color negative in updated versions.

Standard Eastman Kodak edge coding.

History

The introduction of This is Cinerama in September 1952, set off a wave of technical innovations in movie production as various studios competed to create their own widescreen formats, such as CinemaScope, VistaVision, and Todd-AO. Their intention was to find single-camera solutions that could avoid the pitfalls and problems inherent in production and presentation in the three-camera and three-screen Cinerama process. Walt Disney, who had been impressed with the format, chose to go an entirely different route.

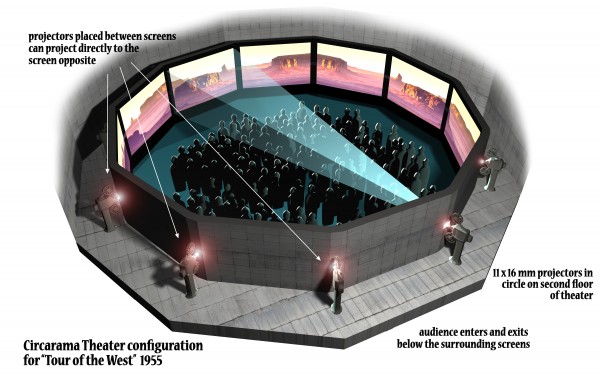

Disney tasked Ub Iwerks, his go-to problem-solver, with finding a way to create what he called “Cinerama in Surround” – a full 360-degree multi-screen presentation. Working with Roger Broggie, manager of the Disney Studio Machine Shop, and Bob Otto, their chief mechanical engineer, Iwerks came up with the idea of a circle of cameras on an aluminum platform. They only had a few months in which to design the camera and theater projection system, as well as to complete production and editing of the new film in order to premiere the attraction at the 1955 opening of Disneyland in Anaheim. They knew the system had to employ an odd number of cameras, so that in the theater each projector could be positioned directly opposite its corresponding screen. Dividing the theater into 11 screens seemed the best choice, since it simulated a pleasing, widescreen look and worked well mathematically, as well. The team also realized that so much film would be passing through 11 cameras that 16mm made greater economic sense than the better image quality that 35mm film would provide.

The producer for Walt Disney Productions was William H. Anderson, with the studio’s Roger Broggie acting as technical advisor. A Tour of the West was sponsored by American Motors, with Russ Haverick working as unit manager and Jack Whitman as cameraman. Peter Ellenshaw, famed studio matte painter, designed the storyboards for each locale and directed the 12-minute film. Ellenshaw and his crew filmed from a boat near Newport Beach; on the roof of a Nash Rambler station wagon in Monument Valley in Arizona; from a B-25 aircraft flying over Hoover Dam; and poolside at a Las Vegas casino/resort. A highlight for audiences was an under-cranked shot (8 fps, which tripled the speed of the action) on a hook-and-ladder fire truck racing down Wilshire Boulevard.

The 40-ft diameter, 360-degree attraction was wildly popular with visitors. Multiple lean rails were soon added, to help audiences deal with the vertigo and unsteadiness caused by the firetruck and aerial scenes, during which the entire theater would seem to be moving.

In 1958, noted Disney “True Life Adventure” filmmaker James Algar, was hired to make another 360-degree film using the same Circarama system for the US pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair. America the Beautiful was sponsored by the Ford Motor Company Fund. Originally titled “America: The Land and the People”, the film included footage of Manhattan, Williamsburg, New England’s fall colors, a Kansas wheat harvest, an Oklahoma cattle roundup and scenes in San Francisco, such as driving down swooping, curvy Lombard Street. Foreign attendees waited in queues for hours in order to experience the film, a rousing success that was not lost on the US Information Agency.

During the ongoing Cold War of that era, the film was seen as a means of projecting America’s cultural and technological prowess on the world stage, at trade fairs and exhibitions. Over the next few years, Circarama theaters were built in Switzerland, India, Pakistan, Italy and Morocco. An article about Dhaka in Pakistan reports that America the Beautiful played in a temporary theater, with free entry, starting in 1963 (Jaffor, n.d.). A New York Times article from May 1959 stated the Circarama exhibit was the hit of the Casablanca International Trade Fair, with 18,700 visitors per day viewing the film.

After America the Beautiful closed its initial run at the Brussels World’s Fair, the film played at the American National Exhibition in Moscow for six weeks, with Russian narration. The Soviets were so impressed, they built their own system called Krygovaya Kinopanorama. They made six films about different regions of the Soviet Union – exhibition of the films continues to this day. America the Beautiful later premiered at Disneyland in Anaheim in 1960, where the attraction was sponsored by Bell Telephone. For that presentation, the 16mm original was blown-up optically and projected in 35mm.

Another Circarama film was made in 1959, commissioned by the US Air Force Academy. Two weeks of production footage was photographed on the campus, but plans for a 360-degree theater fell through. The film has never been seen.

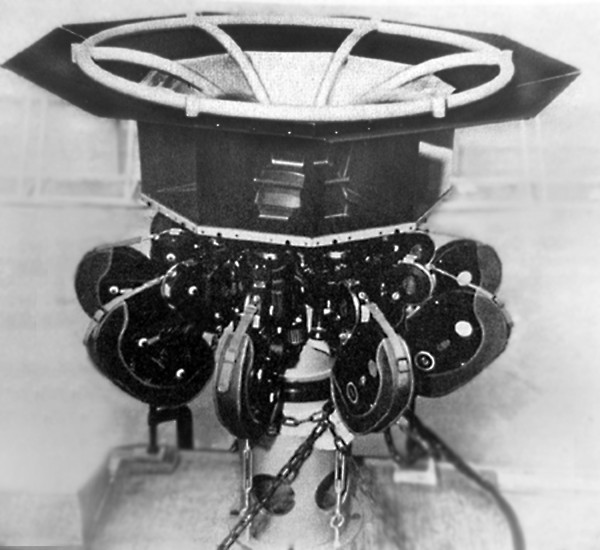

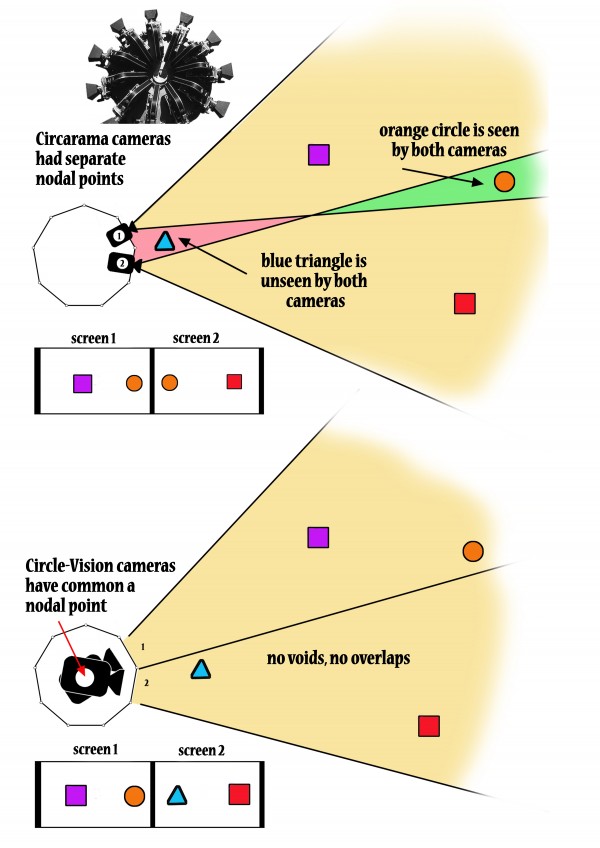

Ub Iwerks wanted to make radical changes before the next Circarama production, which was to be sponsored by Fiat for their pavilion at Expo 61 in Turin, Italy. The entire system was revamped, changing from eleven cameras down to nine and employing a central pedestal with vertically-mounted 16mm Arriflex cameras, which were aimed upwards into 45-degree front-surface mirrors. This was Ub Iwerks’ “perfect solution” to an inherent technical flaw in the original design that had left blind spots and overlaps, as the cameras did not share a common nodal point.

Two extended excerpts from Building Circarama (c. 1962), a demonstration film made by the United States Information Agency (USIA). The surviving copy of the film suffers from heavy color fading.

National Archives Identifier: 53121. Local Identifier: 306.6935mm. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/53121. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, United States.

Initial arrangement of the eleven 16mm projectors and screens for the attraction A Tour of the West that premiered at Disneyland, Anaheim, in 1955.

Illustration by Jeff Blyth.

A Tour of the West crew setting up the Circarama camera system off Balboa Island, Newport Beach, California, using eleven Kodak Cine Special cameras driven by 12-volt war-surplus motors linked by a chain drive for synchronization. On the left, wearing a cap, is Peter Ellenshaw (director) and far right is Jack Whitman (cameraman).

Courtesy of Don Iwerks.

Redesigned Circarama camera (c. 1960) using nine 16mm Arriflex cameras mounted vertically on a pedestal and aimed upward into 45-degree mirrors. This new system eliminated the issue of independent nodal point photography, which had left both blind spots and overlaps between screens in the early versions of Circarama.

Selected Filmography

The 11-screen, 16mm version was sponsored by Ford Motor Company Fund. The film was eventually reshot and expanded, upgrading to 35mm cameras in 1967 and again in 1975 for the bicentennial, sponsored by Monsanto. The film played in its various forms at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and the Magic Kingdom in Florida. The original version of America the Beautiful also played as a US exhibit at various trade fairs and exhibitions as part of an international cross-cultural effort by the US Information Agency in the 1950s and early 1960s.

The 11-screen, 16mm version was sponsored by Ford Motor Company Fund. The film was eventually reshot and expanded, upgrading to 35mm cameras in 1967 and again in 1975 for the bicentennial, sponsored by Monsanto. The film played in its various forms at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and the Magic Kingdom in Florida. The original version of America the Beautiful also played as a US exhibit at various trade fairs and exhibitions as part of an international cross-cultural effort by the US Information Agency in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Filmed and projected in 16mm using 11 cameras and projectors. The 12-minute film, sponsored by American Motors, was continuously screened in Tomorrowland at Disneyland in Anaheim for three years.

Filmed and projected in 16mm using 11 cameras and projectors. The 12-minute film, sponsored by American Motors, was continuously screened in Tomorrowland at Disneyland in Anaheim for three years.

Filmed in 16mm, but projected in 35mm, the 30-minute film played solely at Expo 61 in Turin, Italy, as a centennial celebration of Italian unification. Many years later the film was digitized for use in a museum.

Filmed in 16mm, but projected in 35mm, the 30-minute film played solely at Expo 61 in Turin, Italy, as a centennial celebration of Italian unification. Many years later the film was digitized for use in a museum.

Technology

When forced by a looming deadline into a design for a 360-degree camera and projection system, Ub Iwerks and his team quickly settled on Eastman Kodak Cine Special 16mm cameras. The 200-ft capacity pre-loaded magazines contained their own film advance mechanism and sprocket drive. The magazines could be easily swapped with another set of pre-loaded magazines for quick turnaround in the field after five-and-a-half minutes of shooting. Two 12-volt car batteries drove motors in the base that connected to a common chain drive for synchronization. A control box could turn the system on and off, adjust film speed via a rheostat, and displayed a footage counter. Kodak also happened to make Cine Ektar 15mm lenses that exactly matched the 32.7-degree fields of view required to complete the circle. There was the slightest overlap of images, edge to edge, but that was masked in the theater by black strips called mullions, located at the separations between each screen. These black strips were 6 in (15.2cm) wide when the system had 11 projectors and 9 in (22.9cm) wide in later iterations. An outside firm, the Ralke Company of Los Angeles, was contracted for the synchronization of all projectors and soundtracks, and they also supplied the Eastman 16mm Model 25 projectors. These were chosen because they were exceptionally sturdy – they were required to run 12 hours per day, seven days per week – with an expected lifespan of up to 10,000 hours. A clever device was added to each unit that enabled a switch to a fresh, back-up 1K projection bulb almost instantaneously in the event of a filament burn-out. A central control panel, built by Kinevox of Burbank, alerted the projectionist with a warning light if a film broke. Multiple copies of each screen’s films were stored on the site. Each projector used a 35mm (1.37 in) lens with an f/1.5 aperture, but a variable extension, made by Pacific Optical of Los Angeles, was added to fine-tune the size of the image to exactly fit each screen. Initially the 16mm print was fed to each projector via Busch horizontal platters, but, starting in 1957, the original 16mm film was blown-up to full aperture 35mm Technicolor dye-transfer release prints and the system upgraded to 35mm projectors using traditional reel-to-reel feeds.

When approached about using Circarama for a co-production with Fiat for their Expo 61 exhibit in Turin, Italy, Ub Iwerks used the opportunity to redesign the camera system to address a nagging problem. The original 11 cameras had been snuggly positioned on a compact circular platform, but there were 10-inch (25.4cm) gaps between the lenses – as a result, objects close to camera could fall into blind spots where they would simply disappear from the screens. This happens because the lenses do not share a common nodal point, that theoretical spot within a single camera where all rays of light from the lens converge. Additionally, the field of view of each camera continued outwards – eventually the individual fields of view overlapped each other – meaning objects could appear on more than one screen simultaneously

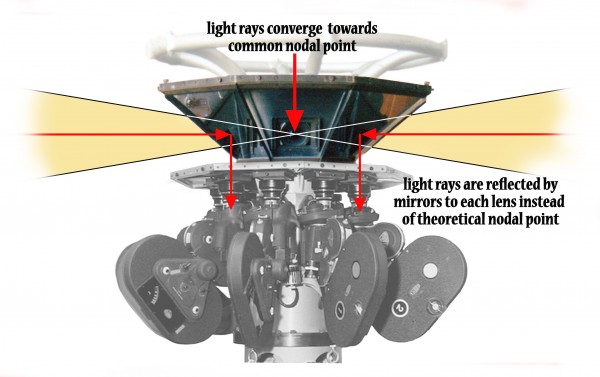

With the revised design of the rig, each of the new Arriflex 16ST cameras would share the exact same nodal point. It may be apocryphal, but supposedly the idea of “folded optics” came to Ub Iwerks in a dream. Whatever the truth, Iwerks had found what he called “the perfect solution”.

Once the new system was built, utilizing nine 12.5mm Taylor-Hobson Cooke lenses, production could begin on the Fiat film, Italia 1961. The cameras were loaned-out, with post-production completed by Disney Studios. Magazine loading and reloading times had increased but the pin-registered cameras rendered superior images. Photography used 16mm Kodak Ektachrome stock which was processed in Los Angeles. B/W 16mm workprints were shipped to Italy for editing. Final optical blow-up to 35mm color release was handled by Disney Studios. Producer Roberto De Leonardis and director Elio Piccon, of Rome’s Royfilm, hired Ub Iwerks’s son Don Iwerks as a camera technician for the three months of shooting. The production shot in Rome, Venice, Naples, Pompeii, Pisa, Florence, Genoa, Monza, Sicily, and finished with scenes in Rhodesia. The film was written and narrated by journalist/historian Indro Montanelli. At 30-minutes runtime, it is the longest 360-degree film ever made.

After the Fiat film, the new system was labeled Circle-Vision to differentiate it from previous iterations of Circarama, as well as to legally distinguish it from the similar-sounding Cinerama. One more major photographic advance occurred in 1964 when the new pedestal and mirror configuration was upgraded from 16mm Arriflexes to 35mm Mitchell GC cameras. From that point on, this format was formally called Circle-Vision 360, although for many the term “Circarama” lives on.

Comparison between independent nodal point photography – which creates blind spots and overlaps – and that of common nodal point photography which was built into the revised Circarama cameras.

Illustration by Jeff Blyth.

Ub Iwerk’s redesign used “folded optics” to create a singular common nodal point for all lenses.

Filming with the revised Circarama rig on the test track at Monza, Italy, for Fiat’s entry to Expo 61 in Turin.

Courtesy of Don Iwerks.

References

Anon. (1955). “Circarama, American Motors’ Circular Screen Presents ‘A Tour of the West’”. Business Screen Magazine, 16:6 (September: special supplement).

Iwerks, Don (2019). Walt Disney’s Ultimate Inventor, the Genius of Ub Iwerks. Glendale, CA: Disney Publishing Group: pp. 126–140.

Iwerks, Don (2023). Interview by Jeff Blyth with Garry Broggie. Ojai, CA. September 6, 2023.

Jaffor Ullah, A. H. (n.d.). “Gulistan – all the while-in my mind… (Part Two)”. https://members.tripod.com/cyber_bangla0/Gulistan/Gulistan2.html (accessed March 14, 2024).

Lightman, Herb A. (1962). “Circling Italy with Circarama”. American Cinematographer , 43:3 (March): pp. 162–163, 188.

Wikipedia (2023). “Circle-Vision 360°”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circle-Vision_360%C2%B0 (last updated December 26, 2023).

Patents

Walter E. Disney and Ub Iwerks. 1956. Panoramic motion picture presentation arrangement, US Patent 2,942,516, filed July 17, 1956, and issued June 28, 1960.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Jeff Blyth is a filmmaker who has made several Circle-Vision 360 films for Walt Disney Imagineering, including Wonders of China (1982) and Reflections of China (2003) for EPCOT, American Journeys (1984) for Disneyland and Walt Disney World (Writer and Co-Director with Rick Harper), Portraits of Canada for EXPO 86, and From Time to Time (aka Timekeeper) for Disneyland Paris and Walt Disney World (1992). He also wrote, produced, and directed the Circle-Vision 200 premiere attraction The Eternal Sea for Tokyo Disneyland (1983). He has authored the book Polishing the Dragons: The Making of EPCOT’s Wonders of China, published by Bamboo Forest Press, 2021. In addition, he has written and directed Light & Life (1991), an IMAX film for the centennial of Philips Lighting, Netherlands and worked as a producer/cameraman on the IMAX films, Behold Hawai’i (1983) and To Fly (1976). He directed the feature film Cheetah for Walt Disney Productions (1988), shot entirely on location in Kenya. He is a member of the Writer’s Guild of America, the Director’s Guild of America, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Documentary Branch.

Don Iwerks, Garry Broggie, Tony Baxter, Gordon Brenner.

Blyth, Jeff (2024). “Circarama”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.