Film Explorer

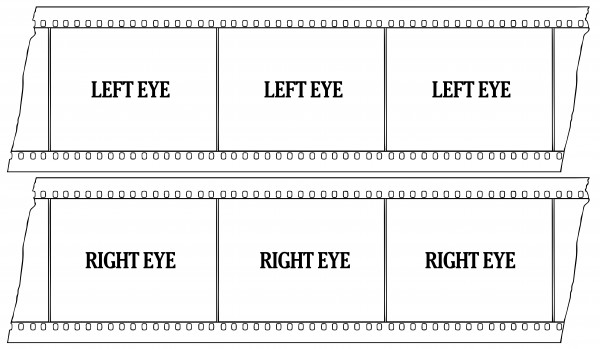

IMAX Solido projected two 70mm IMAX prints in synchronization onto a domed screen – one for the left eye and one for the right eye – to create a 3-D image.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

IMAX Solido 3-D productions were photographed onto two strips of 65mm negative, which were subsequently printed onto two 70mm prints for projection.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

Identification

History

The first 3-D film in the IMAX 15/70 format was We Are Born of Stars, an 11-minute short funded by Japanese conglomerate Fujitsu for its pavilion at Expo 85 in Tsukuba, Japan. Written and produced by IMAX Corporation co-founder Roman Kroitor, it was entirely computer animated (using Fujitsu supercomputers) and used anaglyph (red/blue) technology to display 3-D from a single strip of film. In Tsukuba it was projected on a tilted dome screen, making it the world’s first 3-D film shown on a dome (Ferguson, 2016).

The first full-color 15/70 film in 3-D was Transitions (1986), a 21-minute, live-action short directed by Tony Ianzelo and Colin Low, and produced by the National Film Board of Canada for the Canadian pavilion at Expo 86 in Vancouver. In that theater, two mechanically synchronized IMAX GT 15/70 systems projected onto a flat screen, and the audience wore oversized linearly polarized glasses. It was one of only two IMAX theaters to use two full-size rolling loop film projectors for 3-D. (IMAX later developed a more compact dual-projector 15/70 film system for use in multiplexes called IMAX SR.)

The size, expense, and complexity of running two IMAX projectors led chief engineer William C. Shaw and his team to develop a single projector to project the two reels of 15/70 film needed for 3-D. They began shortly after Expo 86, setting up a “skunk works” in a separate facility across the street from IMAX’s factory in Oakville, ON, to invent and refine the many new technologies needed for the new system (Harris, 2022). The new dual-rotor projector would eventually be installed in flat-screen and dome theaters. (See IMAX 3-D)

The company hired a public relations firm to coin a name for the new “3-D on a dome” system; the result was “Solido” (Low, 2022). A few years later, the name would also be applied to the massive camera the company designed to shoot 3-D on two strips of 15/65 film, replacing the more cumbersome two-camera, beam-splitter rigs used previously. Thus, ironically, the Solido camera was developed too late to shoot the only Solido film.

Based on the success of We Are Born of Stars, Fujitsu asked Kroitor to make another 3-D dome film for Expo ’90 in Osaka, Japan. With the new projector it would be in full color instead of anaglyph. The Solido theater in the Fujitsu pavilion featured a tilted dome 20.9m (68.6 ft) in diameter and seated 285 (IMAX, 1992).

The 20-minute film made for the theater, Echoes of the Sun, was directed by Kroitor and Nelson Max. It combined “3-D computer graphics and live action vignettes … to illustrate how photosynthesis converts sunlight into stored energy in plants, which then provides energy to animals and humans”, according to the official synopsis. The CGI sequences were created by Fujitsu on its supercomputers and the live-action footage was shot with two IMAX 15/65 cameras using wide-angle lenses on a beam-splitter rig (Harris, 2022). It was the only film shot specifically and entirely for IMAX 3-D on a dome.

Echoes was the most popular attraction at the Expo. The next two were director Stephen Low’s The Last Buffalo in Suntory’s IMAX 3D theater and Kroitor’s Flowers in the Sky in the IMAX Magic Carpet in the Sanwa Midori pavilion (Konowal, 2022).

The Fujitsu pavilion was demolished after the Expo, along with nearly all other structures built for the fair.

In 1993, the first of two permanent Solido theaters was built by Fujitsu in Chiba City, near Tokyo. The Fujitsu Dome Theatre seated 315 in a 24.1m (79.2 ft) dome. It closed in 2002.

The only other Solido theater was built in Parc du Futuroscope, France’s theme park of moving images, which had opened near Poitiers in 1987. The Solido theater was the park’s fourth IMAX venue, opening in June 1993 with 295 seats and a 24m (78.7 ft) dome. It operated until 2017 – in 2019, the building was demolished to make way for a new attraction.

Both of these permanent Solido theaters ran Echoes of the Sun for much of their existence, but also showed other IMAX 3-D and 2-D films.

Selected Filmography

Technology

The previous IMAX 3-D system used two 15/70 projectors and linear polarizers to project a 3-D image on a flat screen.

The primary technical challenge of projecting 3-D on a dome is that light reflected off a dome screen is scattered at all angles and loses its polarization, which means that ordinary polarized glasses cannot be used. “[S]o we tried an innovation: active glasses, recently invented for the US Navy,” according to IMAX co-founder Graeme Ferguson (Ferguson, 2012). Active glasses create the 3-D effect by alternately blocking the light going to each eye with some form of shutter.

In the development process, IMAX engineer Gordon Harris specified the characteristics needed in glasses that would be used by hundreds of visitors, in dozens of screenings, 12 hours a day, for the 6 months of Expo ’90 – lightweight, low-voltage, long battery life and easily washed between uses. He first experimented with lead zirconate titanate electro-optic ceramics, but the very high voltages needed to switch between transparent and opaque, made them obviously unsuitable (Harris, 2022).

Harris then turned to liquid-crystal technology, which was still in its infancy in the late 1980s. Liquid crystal panels were able to switch from clear to opaque in a millisecond, making them eminently suitable for the Solido project. The liquid crystal lenses for Expo ’90 were manufactured by Tektronix, and the glasses were made and assembled by IMAX in a workshop set up in Kitchener, ON. They were the first active 3-D glasses to be used by the general public.

The glasses were synchronized to the projector with infrared emitters – also built from scratch by IMAX and its Sonics subsidiary – positioned throughout the theater.

Another challenge was getting enough light on the screen, since even in “clear” mode the liquid-crystal glasses absorbed more than 60 per cent of the system’s light output. The standard IMAX projector used a water-cooled 15kW xenon lamp; the 3-D projector would need two full lamphouses, one for each eye. IMAX engineers used newly developed 3-D computer-aided design software to design the complex optical path that would channel the light from the two upgraded 17.5 kW lamps through the projector’s two fisheye lenses.

To ensure the screen reflected as much light as possible, the perforated aluminum panels of Osaka’s dome skin were given three coats of high-gain paint using an automated spraying system. The gain at screen center was 1.5. (Harris, 2022)

References

Ferguson, Graeme (2012). “Ferguson on Kroitor”. LF Examine (Oct.–Nov.).

Ferguson, Graeme (2016). “Remembering Colin Low”. LF Examiner (April).

Harris, Gordon (2022). Unpublished interview with James Hyder, December 8, 2022.

IMAX Corporation (1992). “International Directory of Theatres with IMAX® or OMNIMAX® Motion Picture Projection Systems”, May 1992.

Konowal, Charles (2022). Unpublished interview with James Hyder, December 5, 2022.

Low, Stephen (2022). Unpublished interview with James Hyder, December 6, 2022.

Patents

Shaw, William C. & Marian Toporkiewicz. 3-D motion picture apparatus. US patent US4971435, filed September 8, 1989, and issued November 20, 1990. https://patents.google.com/patent/US4971435A

Shaw, William C. & Gordon W. Harris. Camera and method of producing and displaying a 3-D motion picture. US patent US 4993828, filed May 11, 1989, and issued February 19, 1991. https://patents.google.com/patent/US4993828A

Shaw, William C. Projected image alignment method and apparatus. US patent US 4997270, filed June 13, 1989, and issued March 5, 1991. https://patents.google.com/patent/US4997270A

Baljet, Anton L., Gerard C. Carter & Gordon W. Harris. Projection synchronization system. US patent US5002387, filed March 23, 1990, and issued March 26, 1991. https://patents.google.com/patent/US5002387A

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

James Hyder worked at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, from 1984 to 1996, where he managed the world's most popular IMAX theater and assisted in the development and production of sveral IMAX films for the museum. In 1997, he founded MaxImage!, the first independent publication dedicated exclusively to the giant-screen industry, renamed LF Examiner in 2000. He was the newsletter's writer, photographer, designer, editor, and publisher for 24 years until its closing, and his retirement, in 2021.

The following individuals provided essential assistance for this article:

Leo Baljet, IMAX Corporation

Gordon Harris, ex-IMAX Corporation

Charles Konowal, producer

Stephen Low, director

Dominque Prisset, Futuroscope

Alvis Wales, ex-IMAX Corporation

Hyder, James (2024). “IMAX Solido”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.