A large format, used primarily for capture and exhibition in giant-screen theaters.

Film Explorer

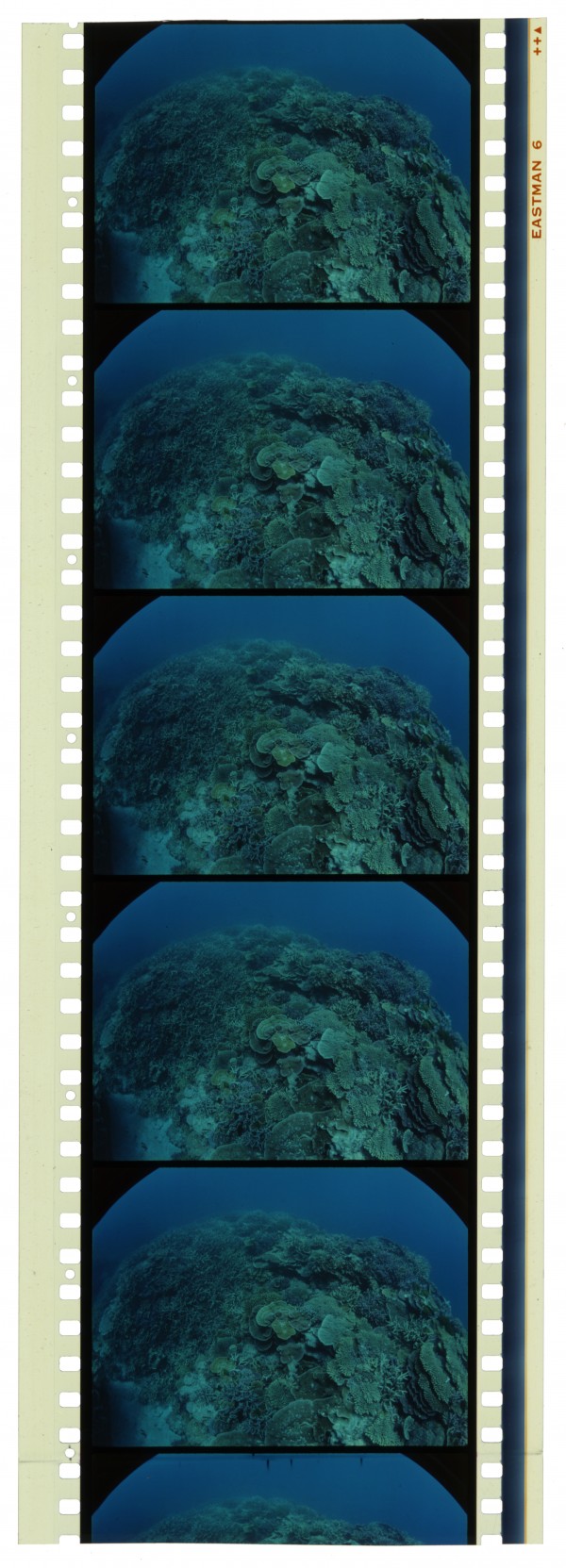

A frame from an 8/70 dome print of Hawaii: Born in Paradise (1987), produced by Destination Cinema, Inc. Printed down from a 15/65 camera negative.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

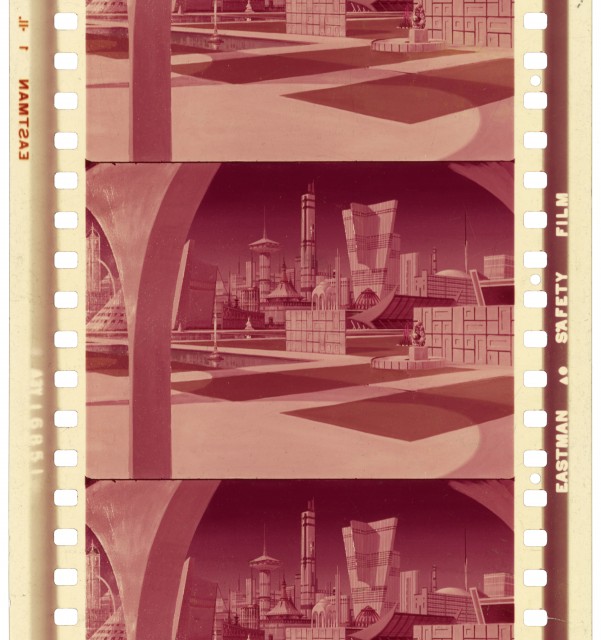

This badly faded 8/70 frame, is of a matte painting by Albert Whitlock used in a 1967 episode of Star Trek (1966–69). How it came to be printed to 8/70 is a mystery. Linwood Dunn may have made it to demonstrate the format to Whitlock, for possible VFX work on Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967).

Francis Thompson Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Left- and right-eye 65mm negatives from Dino Island II 3D (1998), a fully CGI short produced for motion-simulation rides by Iwerks Entertainment.

SimEx/Iwerks. Special thanks to Mark Merrall.

Identification

53.06mm x 37.72mm (2.089 in x 1.485 in) (Projector-gate/aperture-plate sizes were smaller and varied by venue.)

Color

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings. Possibly other film manufacturer markings.

(30 fps for motion simulation)

1 (2 for 3-D).

Eastman Color copies from before 1982 are likely to suffer from color fading.

Variable, all double-system. Initially, playback from analog reel-to-reel multi-track magnetic tape; later digital from CD, and other formats.

52.83mm x 37.59mm (2.080 in x 1.480 in) [Hummel, 2001: p. 16].

Color

Standard Eastman Kodak edge markings. Possibly other film manufacturer markings.

History

In the mid- to late 1960s, studios, producers, and special-effects companies, were experimenting with various methods to improve the quality of optical visual effects – including the use of unconventional film formats and configurations. The standard 70mm format, with a 5-perforation tall frame, had long been used in various permutations for capture, post-production and exhibition – but, its wide aspect ratio of 2.21:1, or more, was not suitable for films with more conventional ratios.

Around this time, at least one Mitchell 65mm camera was modified for an 8-perforation pulldown (increasing the height of the image from the standard 5-perf), to capture visual effects (VFX) footage (Najar, 2024). (Camera film stock is 65mm wide; print stock is 70mm, with the extra 5mm used in some systems for magnetic-stripe sound tracks.) The huge resulting 8-perf frame (known as 8/65 or 8/70) – more than six times larger than Academy-ratio 35mm – would retain higher image quality across multiple generations of optical printing.

Special effects pioneer Linwood G. Dunn, founder of Film Effects of Hollywood (FEOH), was probably the first to conduct tests using 8/65, and even recommended the format to VFX supervisor Al Whitlock for effects on Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967). But there is no record that it was ever actually used for that, or any other, production. Dunn also considered testing 10-perf and 12-perf 65mm (Dunn, n.d.).

In 1973, FEOH developed an experimental 3-D format called Dynavision, which would have eliminated the expense, complexity, and visual imperfections of previous two-strip systems. It was an 8-perf pulldown with two 4-perf frames in an over-under arrangement (left eye over right), yielding an aspect ratio of 2.77:1. “One of the interesting and important advantages of the Dynavision 65mm 8-perf system is that it can be reduced to standard 35mm or 1.85:1 aspect ratios without the loss of important information.” (Dunn & Weed, 1974.)

A demo film, 3-Dynavision, was reportedly made using 3-D material from two European films, as well as 65mm 3-D test footage shot by Colin Low, of the National Film Board of Canada (Sammons, 1992: p. 94). (Low would go on to co-direct the first IMAX 3D film, in 1986.) However, FEOH abandoned the Dynavision project, and no films were ever produced, or commercially released, in the format (Hayes, 2014). Oddly, in some circles (including, to this day, on Wikipedia), the term Dynavision would stick, somehow becoming synonymous with 2-D 8/70, even though it was never an official brand or trade name of any company using that format.

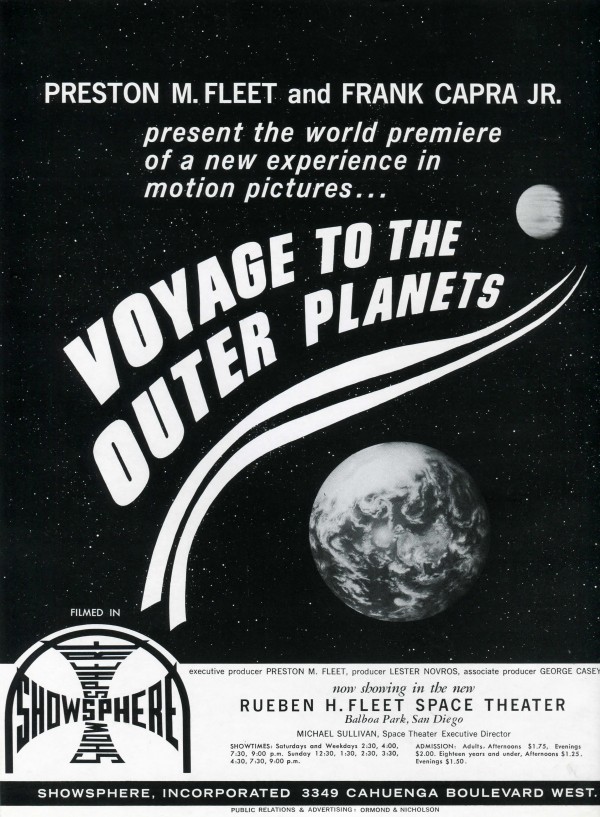

In 1969, at about the same time the founders of IMAX Corporation were developing the 15-perf, 70mm IMAX format in Canada, California filmmakers George Casey, Lester Novros, and Frank Capra, Jr., founded ShowSphere, Inc.: “to develop 70mm film technology for museums and commercial venues” (Oliver, 2000: p. 16). They planned to build theaters and make films using the 8/70 format.

One of the first such theaters was expected to be the Reuben H. Fleet Space Theater in San Diego, a planetarium with a 23.2m (76-ft) tilted dome screen. Novros’ production company, Graphic Films, Inc. (founded in 1941), used 8/65 to shoot Voyage to the Outer Planets, the Fleet Theater’s opening multi-media presentation, in 1973. In PR materials from the time, the film was said to have been “filmed in ShowSphere” (ShowSphere, n.d.).

Fleet’s management decided to install an IMAX 15/70 projector instead of a ShowSphere 8/70 system, making it the world’s first OMNIMAX theater. However, Voyage was actually shot on 8/65, because the few 15/65 cameras extant at the time could not be run in reverse – this ability was required for the multiple passes needed for some of the in-camera process shots. Voyage’s director, Colin Cantwell, used the 65mm Todd-AO camera that FEOH had modified with an 8-perf pulldown for 3-D Dynavision, to shoot footage of spacecraft and planet models. The finished film was then blown up to 15/70 (Casey, 1973: p 990). Thus, Voyage became the first publicly screened film shot on 8/65.

ShowSphere, Inc., didn’t end up constructing any 8/70 theaters – the format lay dormant for both capture and exhibition for a decade and a half.

By the mid-1980s, IMAX Corp. (founded in 1967) had installed more than 30 permanent 15/70 theaters, and had no significant competition in the giant-screen cinema market. But, its systems were large and expensive, affordable only for expos, theme parks, and major museums. At about this time, competitors emerged to offer more economical options.

Fred Hollingsworth III had founded Omni Films International (OFI) in 1974 with Cinema 180 – 5-perf 70mm, projected onto a dome through a fisheye lens. OFI marketed the system, along with a selection of short films it produced, mainly to amusement parks and theme parks. Most Cinema 180 theaters had no seats – audiences stood for the 10–13-minute duration of the films, which typically featured point-of-view scenes filmed from roller coasters, race cars, and other thrill rides. The company claimed 175 installations, at its peak (Hauerslev, 2021).

In the late 1980s, OFI also began offering several 8/70 formats, including OmniVision, projected on a tilted dome; MagnaVision, on a flat screen; and ESI 3-D, an 8/70 over/under polarized 3-D system, with an aspect ratio of 2.26:1 (similar to FEOH’s original Dynavision concept), projected onto an aluminized-fabric flat screen.

The world’s first permanent 8/70 theater was an OmniVision dome in South Korea’s Seoul Land theme park – opened in 1987. Over the next few years, OFI opened 12 more OmniVision and MagnaVision theaters: in Finland, Japan, Taiwan, and the US (Iwerks, 2000). Despite this handful of 8/70 sales, the company’s primary focus remained its 5/70 Cinema 180 system.

OFI was one of the first companies to offer motion-simulation experiences, introducing Motion Master moving theater seats in 1987. Most of its motion installations used 5/70 film, but a handful were equipped for 8/70 (Ibid.).

In 1985, Don Iwerks and Stan Kinsey founded Iwerks Entertainment. Don was the son of Ub Iwerks, Walt Disney’s first business partner, and co-creator of Mickey Mouse. Don had worked at the Walt Disney Company for 30 years, where he had developed innovative film technologies, including Circle-Vision 360, a nine-camera 35mm system. Iwerks started installing 8/70 projectors in 1992, the first of which were manufactured by Ballantyne. Eventually its 8/70 theaters were operating in 17 countries (LFexaminer.com, 2024).

While OFI had focused mainly on amusement parks, Iwerks also marketed 8/70 systems to world’s fairs, museums, and science centers – where IMAX had achieved significant success. With a smaller frame size, 8/70 was suitable for smaller venues, and clients who couldn’t afford an IMAX system. Apart from a smaller physical footprint and lower print costs, another factor that made operating an 8/70 theater less expensive than IMAX was that the projectors could be purchased outright. In contrast, IMAX Corp. leased most of its patented projection systems, requiring theaters to pay a percentage of the box office to IMAX, as well as buy into a mandatory service contract.

Iwerks offered 8/70 systems for both flat-screen and dome theaters. Originally branded IwerkSphere, Iwerks’ 8/70 dome installations were later called CineDome 8/70. In 1994, after certain IMAX patents expired, Iwerks also began selling 15/70 projectors (manufactured by Cinema Development Company) – the dome versions of which were branded CineDome 15/70. In 2000, Iwerks rebranded all its systems as Extreme Screen, dropping the CineDome trademark in 2005.

Iwerks became the largest provider of 8/70 systems, with more than 60 permanent non-ride theaters, of which 25 were domes, plus a handful of temporary installations at expos (Iwerks, 2000). In 1994, Iwerks acquired OFI in a $17 million deal, taking over its film library and assuming support for dozens of theater clients (Hauerslev, 2021). In 2002, the company merged with Canadian motion-simulator supplier SimEx, becoming SimEx/Iwerks (Screen Daily, 2001).

Apart from temporary installations and multiplexes (see below), about 100 permanent theaters, mostly in museums, theme parks, and other special venues, installed 8/70 film projectors between the late 1980s and 2007. The peak year was 2004, when 92 theaters using the format were operational (LFexaminer.com, 2024).

IMAX Corp. did not allow non-IMAX theaters to book its original productions, but the majority of other independent giant-screen producers released their films to both 8/70, and IMAX theaters. Out of roughly 350 independent giant-screen films released between 1973 and 2015 (the last year a new film was printed to 8/70), at least 90 were available in 8/70 (LFexaminer.com, 2024).

From the 1990s into the 2000s, 8/65 was used as a capture format for giant-screen films intended specifically for 8/70 theaters, or for blowup to 15/70 – either as a cost-saving measure, or in situations where using the larger 15/65 cameras was not practical. Giant-screen producers preferred to shoot 15/65, since the majority of their customers were 15/70 theaters. Only about ten films have been shot entirely, or mostly, on 8/65 to date, although as of 2024, 8/65 remains in limited use as a camera origination format (LFexaminer.com, 2024).

A few Hollywood features that have been released on IMAX film were partially shot on 8/65 film (and sometimes 5/65) in addition to 15/65, including Star Trek: Into Darkness (2013) and Mission: Impossible, Ghost Protocol (2011).

“In a movie like Mission: Impossible [Ghost Protocol] the 15-perf film was reserved for the shots where having that extra detail in the negative would be useful, like in an establishing shot or in one of those ‘wow’ moments where you really want to impress. 8-perf is then used for everything else, since you get more frames per foot of film and since the cameras are more maneuverable.” (Schiff).

In addition, in an echo of the format’s origins, Spider-Man 2 (2004) used 8/65 for some VFX shots (IMDb.com).

Although many IMAX film theaters were 3-D capable, most 8/70 theaters were not. Only nine 8/70 theaters were equipped for 3-D, all with dual electronically-interlocked projectors. But only 16 3-D films were ever printed to 8/70, so most screenings in those theaters were of 2-D titles (LFexaminer.com, 2024).

With the arrival of the DCI standard for digital projection in 2005, and the improvement of digital cameras over the decade that followed, the use of 8/70 for exhibition and 8/65 for capture declined steadily. The last 8/70 projectors were installed in 2007, and the final working system – at the Paulucci Space Theater in Hibbing, MN – was decommissioned in 2020 (LFexaminer.com, 2024).

8/70 in Multiplexes

In the mid-1990s, IMAX Corp. began marketing its film systems to commercial exhibitors, and, by 2000, had installed 30 in US multiplexes. This occurred during several years of competitive overbuilding across the industry, which ultimately led several chains filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy that same year (2000).

At least two companies, United Artists and Edwards, used the Chapter 11 process to break their IMAX systems leases. IMAX reclaimed the projectors, and UA and Edwards replaced them with 8/70 systems. Several smaller chains also equipped a handful of screens with 8/70 at about the same time (LF Examiner, 2001).

The primary impetus for these 8/70 installations was Walt Disney Pictures’ announcement that it would release some of its films to IMAX and 8/70 theaters. This followed the successful exclusive run of Fantasia 2000 in 84 IMAX theaters during the first four months of the year – most of those venues brought the film back for a second run that summer.

In 2002, Disney released 15/70 and 8/70 prints of four titles: Beauty and the Beast (1991), Ultimate X (2002), Treasure Planet (2002), and The Lion King (1994). The Young Black Stallion (2003) was shot on 15/65 and released to IMAX theaters, but not to 8/70. This brief run ended Disney’s foray into giant screens until the digital era (LF Examiner, 2002).

In all, about 30 8/70 systems were installed in multiplexes – after 2002 some of those theaters tried booking short nature and science documentaries from independent giant-screen producers, but with little success. Some of the projectors were double-format, and could also run 35mm, but most were never again used for 8/70. The 8/70-equipped Edwards and UA screens were acquired by Regal Cinemas and converted back to IMAX (LF Examiner, 2003).

A 1973 promotional brochure for ShowSphere, Inc., highlighting the company’s role as producer of the debut film for the Fleet Space Theater in San Diego, which was projected in 15/70.

Courtesy of Ammiel Najar, Graphic Films.

The crew of Bugs! (2003), filming with an Iwerks 8/70 3-D beamsplitter rig, on location near Kuching, East Malaysia, July 2002.

Photo by James Hyder. © 2002 by Cinergetics, LLC.

Selected Filmography

40 mins. 3-D. Bugs! explores the dramatic, and savage, lives of a praying mantis and a beautiful butterfly, in the rainforests of Borneo. A rare example of a film originated on 8/65 3-D.

40 mins. 3-D. Bugs! explores the dramatic, and savage, lives of a praying mantis and a beautiful butterfly, in the rainforests of Borneo. A rare example of a film originated on 8/65 3-D.

20 minutes. The signature film for the Shiretoko Nature Center, Hokkaido, Japan.

20 minutes. The signature film for the Shiretoko Nature Center, Hokkaido, Japan.

39 minutes. The signature film for the 8/70 theater at the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, CA, tells the story of its construction by newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst.

39 minutes. The signature film for the 8/70 theater at the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, CA, tells the story of its construction by newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst.

20 minutes. The signature film for the 8/70 theater at Dolly Parton’s Dollywood theme park in Tennessee, celebrates the wonders and people of the Great Smoky Mountains.

20 minutes. The signature film for the 8/70 theater at Dolly Parton’s Dollywood theme park in Tennessee, celebrates the wonders and people of the Great Smoky Mountains.

132 minutes. The IMF is shut down when it’s implicated in a bombing in the heart of the Kremlin, causing Ethan Hunt and his new team to go rogue, in an effort to clear their organization’s name. Partially shot on 8/65, 5/65, and 15/65.

132 minutes. The IMF is shut down when it’s implicated in a bombing in the heart of the Kremlin, causing Ethan Hunt and his new team to go rogue, in an effort to clear their organization’s name. Partially shot on 8/65, 5/65, and 15/65.

45 minutes. Concert film showcasing the popular boy band.

45 minutes. Concert film showcasing the popular boy band.

23 minutes. The signature film for the 8/70 theater at Space Center Houston, TX, follows the lives of several astronaut candidates, from initial selection through actual spaceflight.

23 minutes. The signature film for the 8/70 theater at Space Center Houston, TX, follows the lives of several astronaut candidates, from initial selection through actual spaceflight.

28 minutes. Captured on 8/65, but printed to 15/70 for exhibition. The debut film for the Reuben H. Fleet Space Theater, San Diego, CA, portrays a manned mission to the outer planets in the year 2348 – when the planets will be in a favorable alignment for a three-year journey of exploration.

28 minutes. Captured on 8/65, but printed to 15/70 for exhibition. The debut film for the Reuben H. Fleet Space Theater, San Diego, CA, portrays a manned mission to the outer planets in the year 2348 – when the planets will be in a favorable alignment for a three-year journey of exploration.

Technology

Conventional projectors subject film prints to significant acceleration and deceleration as each frame is intermittently pulled down, held motionless while light is projected through it, then pulled down again to project the next frame.

As the frame size gets larger, the forces associated with these movements increase, and the founders of IMAX Corp. learned in the late 1960s that 15/70 IMAX film was too large to be reliably transported using conventional intermittent movement – the print’s sprocket holes would become damaged after only a few passes through the projector, and would eventually tear through. They learned of a novel movement mechanism called the “rolling loop”, invented by Australian engineer Ron Jones for use with 35mm film, and acquired the patent. IMAX chief engineer William C. Shaw subsequently adapted and enhanced it for 15/70.

A rolling-loop projector moves the film continuously on a large circular rotor. As each frame approaches the gate, a loop is built up in a wave-like motion perpendicular to the plane of travel. The film’s sprocket holes are not used to accelerate, then decelerate, the film – only to register it momentarily in the gate, while light passes through. Thus, the film is handled more gently, resulting in tolerable wear, and the projected image is much steadier than with conventional film transport (Smith, 1991: p. 13). The rolling loop technique is now used for all IMAX film projectors.

Unlike 15/70, the smaller 8/70 frame – at just over half the area – could be handled reliably and safely by conventional Geneva intermittent movements. Thus, manufacturers of 70mm projectors could quite easily modify existing 5-perf 70mm systems to project 8/70 film – permitting them to be much less complicated, and less expensive, than the massive, dedicated IMAX film systems.

IMAX Corp. patented certain key features of its rolling loop projector, giving it de facto exclusivity on the 15/70 format, from its invention in 1970 until 1993, when the first non-IMAX 15/70 projector was installed. However, there were no patents or trademarks on any aspect of the 8/70 format, and therefore no legal or practical obstacles to producing and marketing 8/70 projectors. From 1987 to 2007, more than a dozen manufacturers did so, including: US-based MEGAsystems (now defunct; 30 theaters), and Christie (5); Germany’s Kinoton (16); Cinemeccanica in Italy (4); and Japan’s Gakken and Japan Victor (4 each) (LFexaminer.com, 2024).

Because there was no patent or trademark holder to establish standards, there is no “official” 8/70 frame size. Camera-aperture and projector-gate dimensions varied slightly between manufacturers – but, these differences were not significant enough to impede interoperability.

After installing Ballantyne 8/70 projectors with conventional movements for several years, Iwerks acquired US-based Pioneer Technology Corp (no relation to the Japanese electronics firm), which had developed the Linear Loop projection system. Linear Loop was essentially a straightened-out version of IMAX’s rolling loop – that is, instead of creating a loop on a large rotating circular rotor, the Linear Loop accomplished the same effect while transporting the film in a straight line. Iwerks manufactured linear loop systems in its Burbank facility in 4/35 (for motion simulators), 8/35, 8/70, and 10/70 configurations. (IMAX did not make film projectors in any format other than 15/70.) The first 8/70 linear loop projector was installed at the Fleischmann Planetarium in Reno, NV, in 1994. Eventually, at least 60 linear loop systems in all formats were installed (Stults, 2023).

In 2000, Iwerks’ L. Ron Schmidt won a Scientific and Technical Academy Award for the “concept, design and engineering of the Linear Loop Film Projector” at the 72nd Oscars ceremony.

Sound

Eight-perf 70mm theaters used a variety of audio systems and configurations, all double-system: i.e., the sound track was not on the film print, but on a separate synchronized playback machine. Although there was some variation, most 8/70 installations had six channels, so as to be compatible with films made for IMAX theaters – placing speakers behind the screen at the left, center, right, and top; and at the left rear and right rear of the auditorium.

Playback machines were varied, but most installations used analog reel-to-reel tape decks – usually ½-in (1.27cm) eight-track, which allowed for a second, or third, narration language, if needed. Some Iwerks theaters used 2-in (5.08cm) analog reel-to-reel tape. In a few of its earliest digital sound systems, Iwerks experimented with LaserDisc for audio playback, but later switched to proprietary digital systems using Compact Disc (Barnett, 2023).

This promotional sample displays the relative sizes of several standard 35mm and 70mm print formats, including 8/70 (labeled 8P). omotional sample displays the relative sizes of several standard 35mm and 70mm print formats, including 8/70 (labeled 8P).

Film Atlas collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

References

Barnett, David (2023). Unpublished interview with the author (Oct. 15).

Casey, George (1973). “The Production of ‘Voyage to the Outer Planets’”. American Cinematographer, 54:8 (Aug): pp. 990–1018.

Dunn, Linwood G. (n.d.). papers. Unpublished collection. Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Los Angeles, CA. Reviewed May–June 2024

Dunn, Linwood G. & Don Weed (1974). “The Third Dimension in Dynavision”. American Cinematographer, 55:4 (Apr.): pp. 450–1.

Hauerslev, Thomas (2021). “Introduction to Cinema 180” (Mar. 5). Last updated July 28, 2024. https://www.in70mm.com/presents/1974_cinema_180/introduction (accessed Aug. 31, 2024).

Hayes, John (2014). “‘You see them WITH glasses!’… A Short History of 3D Movies”. Last modified Sept. 14, 2014. https://widescreenmovies.org/WSM11/3D.htm (accessed Aug. 31, 2024).

Hummel, Rob (2001). American Cinematographer Manual (8th edn). Hollywood, CA: The ASC Press.

IMBd (n.d.). https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0316654/technical/?ref_=tt_ov_at_dt_spec (accessed Oct. 28, 2024).

Iwerks Entertainment (2000). Unpublished client list spreadsheet, provided to the author by SimEx/Iwerks.

LF Examiner (2001). “Edwards Shuts IMAXes”. LF Examiner (Aug.): p. 1.

LF Examiner (2002). “The Large-Format Films of 2002”. LF Examiner (Jan.): p. 1.

LF Examiner (2003). “Special Report: Large-Format Theaters in 2002”. LF Examiner (Feb.): p. 1.

LFexaminer.com (2024). Query of LF Examiner database of theaters and films. https://lfexaminer.com (retrieved Aug. 31, 2024).

Najar, Ammiel (2024). Unpublished interview with the author (Mar. 4).

Oliver, Myrna (2000). “Les Novros: Documentary Filmmaker, USC Professor”. Los Angeles Times (Sep. 23). https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-los-angeles-times/109612937/ (accessed Aug. 31, 2024).

Reyna, Christopher (2022). Unpublished interview with the author (Dec. 22).

Sammons, Eddie (1992). The World of 3-D Movies. (Delphi. 1992.) Available at: https://thefsu3dproject.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/sammons-two3dm-300dpi-c.pdf (accessed Aug. 31, 2024).

Schiff, Evan (2012). “Mission: Impossible 4 Formats and Aspect Ratios”. https://www.evanschiff.com/articles/mission-impossible-4-formats-and-aspect-ratios (accessed Oct. 28, 2024).

Screen Daily (2001). “Iwerks Entertainment to merge with SimEx” (Sep. 9). https://www.screendaily.com/iwerks-entertainment-to-merge-with-simex/406819.article (accessed Aug. 31, 2024).

ShowSphere (n.d). ShowSphere is the Total Field of Human Vision. PR brochure.

Smith, Barrie (1991). “A Magic Carpet – and 3D with LCDs”. Electronics Australia , 53:1 (Jan.): pp. 12–15

Stults, Don (2023). Unpublished interview with the author (Aug. 29).

Patents

Schmidt, Leland R. Motion Picture Projection Apparatus. US patent 5,341,182, filed January 14, 1993, and issued Aug. 23, 1994.

Schmidt, Leland R. Film Advance Mechanism for Motion Picture Apparatus. US patent 5,633,696, filed August 23, 1995, and issued May 27, 1997.

Schmidt, Leland R. Film Advance Mechanism for Motion Picture Apparatus. US patent 5,841,514, filed April 4, 1997, and issued Nov. 24, 1998.

Compare

Related entries

Author

James Hyder worked at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, from 1984 to 1996, where he managed the world's most popular IMAX theater and assisted in the development and production of sveral IMAX films for the museum. In 1997, he founded MaxImage!, the first independent publication dedicated exclusively to the giant-screen industry, renamed LF Examiner in 2000. He was the newsletter's writer, photographer, designer, editor, and publisher for 24 years until its closing, and his retirement, in 2021.

Special thanks to Ammiel Najar, formerly of Graphic Films, Inc., for sharing his extensive knowledge, and for his extraordinary dedication in helping the author track down the early history of the 8/70 format. The following individuals also provided essential assistance in preparing this article: David Barnett, ex-Iwerks; Bob Dean, ex-OmniFilms and ex-Iwerks; Michael Frueh, SimEx/Iwerks; Thomas Hauerslev, in70mm.com; Don Iwerks, founder of Iwerks; Stephen Low, Stephen Low Company; Mark Merrall, ex-Iwerks; Christopher Reyna, ex-Imagica; Eric Rodli, ex-Iwerks; Bob Rogers, BRC Imagination Arts; Scott Shepley, ex-SimEx/Iwerks; Don Stults, ex-Iwerks.

Hyder, James (2025). “8/70”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.