An applied-color process, based on the selective application of color to B/W film prints developed by Max Handschiegl and Alvin Wyckoff.

Film Explorer

Geraldine Farrar as French heroine Jeanne d’Arc burning at the stake at the end of Cecil B. DeMille’s Joan the Woman (1916). A popular color motif for the Handschiegl process was the mutable element of fire – typically colored in a rich amber yellow – which served as both a chromatic sensation and a special effect in the film.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Natural History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

Mary Pickford in front of the American flag in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Little American (1917). Next to decorative images of women, the flag was a popular color motif for many color processes during this time. Yet, while Pickford’s hair and white skin have been given a soft beige color that renders her with greater fidelity, the flag, by contrast, appears not to have been colored authentically as it lacks the signature blue – although it is possible that the dye may have faded.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Natural History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

35mm nitrate print of Up in Mabel’s Room (1926). Actor Harrison Ford’s face fills with an orange rage from bottom to top with the addition of a Handschiegl coloring effect.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

The dance-hall sequence in Pál Fejős’s Lonesome (1928). This is an example of Handschiegl’s use of multicolor: subtly blending yellows, blues, and pinks throughout the scene, in combination with a variable-density Movietone track (not colored). While festive occasions were typically used to display film colors that were narratively motivated, the simultaneous presence of diegetic music reinforces the impression of the sensual spectacle.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

23.65mm x 17.73mm (0.931 in 0.698 in). Most films released with Handschiegl coloring were photographed and released using the full silent aperture. In some rare cases, like Lonesome (1928), Movietone aperture was used.

Bell and Howell (BH) negative perforations from 1916 to 1925; Kodak Standard (KS) positive perforations from 1925 onwards.

Color dyes applied to a processed B/W emulsion.

Eastman Kodak markings following the US standards, appearing either in black on a colored background, or in a mixture of the colors used in the respective film image area. The general rule is that using more colors for the film image, made the perforation area that much more colorful. As a consequence of the contact pressure, and the remaining excess dyes which were squeezed onto the perforation area, this area is typically characterized by a relatively spotty or blotchy aesthetic effect – sometimes reminiscent of the iridescence of an opal gemstone, or splashes of color from a rainbow.

Variable during silent period; 24 fps for sound films.

1

In projection, it can be hard to distinguish the process from 1920s stenciled films. Next to uniformly colored large surfaces, the process also allows the detailed colorization of small, individual shapes in multicolor that produce extremely “realistic” effects. Because of occasional discrepancies that occur during registration, the dyes may not be completely congruent with the underlying silver image. Yet, in contrast to the cut-out aesthetics of stencil-color, the possibility of the mixing and blending of multiple colors also created smoother color transitions within the film image area. Some secondary sources also speak of the process’, “subtler … texture”, “pastel-like luminosity” and “evocative power”, which apparently surpasses what is possible with stenciled films (Cherchi Usai, 2019, pp. 58–59).

None

The Handschiegl process was compatible with both sound-on-film and sound-on-disc technology.

(sound films only; otherwise silent)

(sound films only)

24.89mm x 18.67mm (0.980 in x 0.735 in).

Orthochromatic or panchromatic B/W negative.

Dependent on negative stock used.

History

The Handschiegl process was an applied-coloring technique, widely used in the United States between the mid-1910s and the late-1920s. It was developed in 1916 by the engraver and lithographer Max Handschiegl, together with the cinematographer Alvin Wyckoff (1919a; 1919b). At the time, both were employed by the American motion picture studio Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, which was formed in the same year. Although deployed on more than fifty features and shorts, the process was predominantly used in short sequences or one-off shots for dramatic effect. It was a costly and complicated artisanal technique, that relied on Max Handschiegl to precisely hand-paint the masks needed to color minute parts of the film frame (Kelley 1931, 230). The selectively colored inserts were typically juxtaposed with tinted and toned elements or segments in B/W or photographic color, thus creating an intriguing effect of chromatic hybridity within a single film.

The Handschiegl process achieved commercial success in the United States, the only country where it was used. Although the technique was originally developed as an in-house system restricted to the Lasky studio, it was applied more widely by other studios when Max Handschiegl began working independently.

Indeed, Handschiegl himself had left the Lasky Studio early on, presumably around 1916 or 1917, before setting up at Sanborn Laboratories, and later independently as the Handschiegl Color Process Corp. in the early-1920s. In 1918, Handschiegl filed two new patents for coloring moving pictures that continued the principle of color transfer, albeit envisaged as a mimetic color film technology.

In the same year, a horrific fire destroyed the color department of the Lasky studio (Harleman, 1918: p. 1145). As a result, the Sanborn Laboratories Inc. in Culver City obtained the rights to the Handschiegl process (Sanborn Laboratories Inc., 1918: p. 1149). In February 1920, Sanborn’s client Special Pictures Corporation advertised their use of the Handschiegl color process as a “new sensation in art color scenic” in a series of travel shorts (Special Pictures Corporation, 1918: p. 2085). This resulted in Famous-Players Lasky suing Handschiegl, and the two other parties, for patent infringement (“Claim Process Rights”, 1920: p. 1).

In 1926, the Handschiegl Color Process lab merged with Kelley Color Films, which continued to offer the process until at least 1931. At the same time, the Kelley Color and Handschiegl processes were combined to offer a new hybrid subtractive imbibition color system, referred to as the Kelley Color-Handschiegl Process. Until his death, on May 1, 1928, Max Handschiegl devoted his time to the improvement of his color transfer machine, the development of trick photography and film-polishing machines. After Handschiegl’s death, Kelley tried to continue the Kelley Color-Handschiegl Process on a limited basis for a few years, but the quality of the coloring seemed to suffer. Meanwhile, the Kelley-Color Company was bought, in turn, by Harriscolor in 1928 (Theisen, 1935: p. 276).

Cecil B. DeMille was another key figure who collaborated with Handschiegl and Wyckoff, to develop the coloring process. Together, they produced several feature films between 1916 and 1918 in which the Handschiegl process was employed: these included, Joan the Woman (1916), The Devil Stone (1917), The Little American (1917), The Woman God Forgot (1917) and The Whispering Chorus (1918). Although the process was advertised at the time as the “Wyckoff process”, the press often referred to it as the “DeMille-Wyckoff process” (DeMille, 1959: p. 175).

The premiere version of DeMille’s historical epic Joan the Woman, which was the first film made with the color process, juxtaposed Handschiegl-colored sequences with B/W, tinted and toned elements. In general, the film was received as a cinematic sensation by both the trade and public press. Although the Handschiegl process was used many times throughout the film, it gained particular attention in the sequence of the climactic burning at the stake of Jeanne d’Arc (Geraldine Farrar).

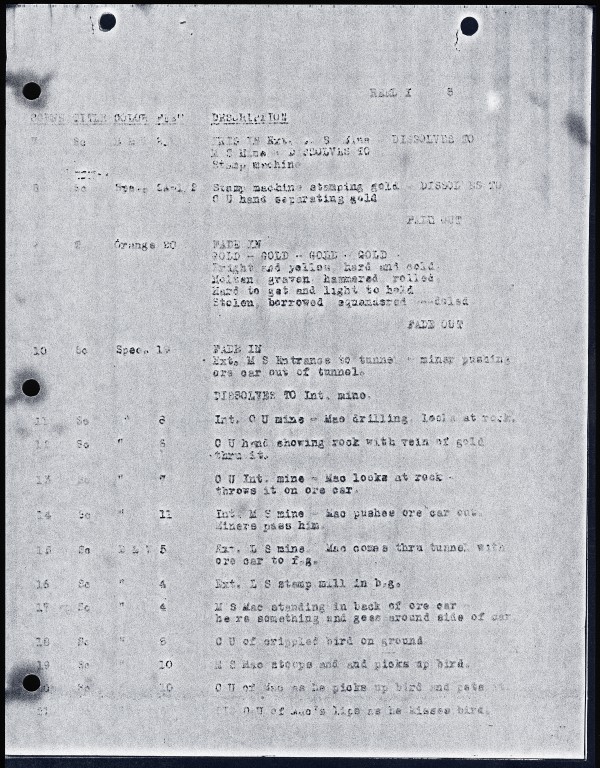

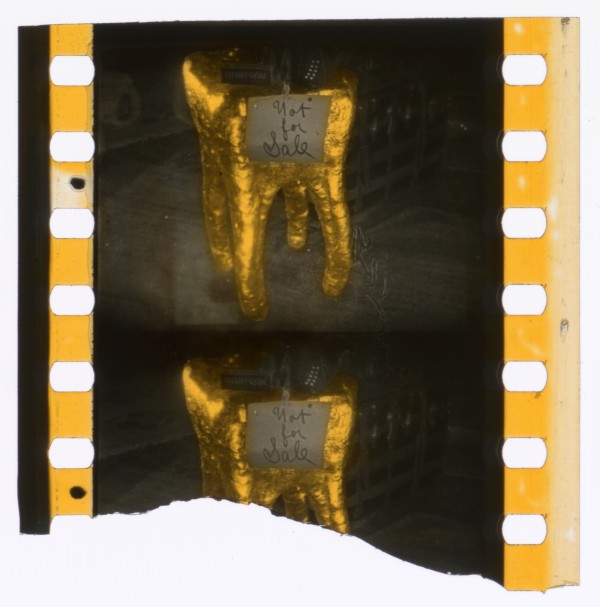

Another famous example, where the process gained critical attention, was Erich von Stroheim’s realist drama Greed (1924) – as released by the newly formed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. The two-hour release version is said to have had all the gold artifacts gold-tinted by means of the Handschiegl process, to underline the theme of gold-money-greed – a stylized, symbolic use of color, for which the film was heavily criticized (Koszarski, 1999: p. 14). In an excerpt from the cutting continuity notes for the beginning of the film, it becomes apparent how the Handschiegl inserts (“Spec. Col.”) were cut into the film prints, sometimes back and forth over a series of shots, thus creating a hybrid color film aesthetic.

Among its main competitors were hand- and stencil-coloring, as well as Paramount’s later in-house variant of Handschiel, Quadricolor. Hand-coloring, as practiced, for instance, by the hand-colorist Gustav Brock in the 1920s, was, like the Handschiegl process, preferred for the coloring of flames and smoke – but its use was limited, because every print had to be colored-in painstakingly by hand. As for mechanization, Pathéchrome – also called Pathécolor – was a more immediate rival (Kelley, 1931): both were applied color processes that relied on a variation of a stencil system (either blocked-out by hand, or cut out with the help of a pantograph) and on the principle of color separations (either matrices, or stencils, depending on the number of dyes deployed). And, significantly, both were able to create the impression of a “lifelike” multicolored film image that could easily be mistaken for photographic color. Yet, in contrast to the hard lines of color that came with the stencil, Handschiegl created smoother transitions of color. Quadricolor, however, despite its aesthetic similarities to Handschiegl, was generally utilized for title cards and intertitles and typically featured three or more colors.

Selected Filmography

Handschiegl spot coloring of Hank Martin’s (Will Rogers) blushing.

Handschiegl spot coloring of Hank Martin’s (Will Rogers) blushing.

Dramatic coloring of the destructive fire that engulfs an orphanage in lavish amounts of yellow, orange and red.

Dramatic coloring of the destructive fire that engulfs an orphanage in lavish amounts of yellow, orange and red.

Handschiegl spot coloring was used for all golden items (e.g., tooth, canary cage, dishes) throughout the film, with a yellow-golden hue, also included red bloodstains on the golden coins, in the desert scene at the end of the film.

Handschiegl spot coloring was used for all golden items (e.g., tooth, canary cage, dishes) throughout the film, with a yellow-golden hue, also included red bloodstains on the golden coins, in the desert scene at the end of the film.

Handschiegl effects were used throughout the film for the colors of yellow (the sword scene); yellow-orange (scene with the pyre); amber and green (when Joan prepares to obey the command of her “inner voice”); and blue (scene with the cross of Jesus Christ in the dungeon, as well as the epic war scene at the end of the film).

Handschiegl effects were used throughout the film for the colors of yellow (the sword scene); yellow-orange (scene with the pyre); amber and green (when Joan prepares to obey the command of her “inner voice”); and blue (scene with the cross of Jesus Christ in the dungeon, as well as the epic war scene at the end of the film).

A short sequence of the American flag was multicolored by Handschiegl – colored authentically in blue and red (with the whites of the silver image) – in an amber-colored night scene.

A short sequence of the American flag was multicolored by Handschiegl – colored authentically in blue and red (with the whites of the silver image) – in an amber-colored night scene.

With the application of flesh-tone colors, Handschiegl enhanced the shot of Mary Pickford standing in front of a red-colored American flag.

With the application of flesh-tone colors, Handschiegl enhanced the shot of Mary Pickford standing in front of a red-colored American flag.

Multicolored use of the Handschiegl process in the scenes on the beach at Coney Island, with Glenn Tryon and Barbara Kent in blue and yellow, in the middle of the film; transitioning, in the lighting displays of the amusement park, to vivid blues, purples, magentas, and yellows. The daydream in the dance hall is also selectively colored blue, magenta and golden-yellow – with a golden-yellow crescent moon and a golden palace, against a blue-colored sky. Additionally, in the rollercoaster scene, the wheel of the cart catches on fire, with yellow-orange flames.

Multicolored use of the Handschiegl process in the scenes on the beach at Coney Island, with Glenn Tryon and Barbara Kent in blue and yellow, in the middle of the film; transitioning, in the lighting displays of the amusement park, to vivid blues, purples, magentas, and yellows. The daydream in the dance hall is also selectively colored blue, magenta and golden-yellow – with a golden-yellow crescent moon and a golden palace, against a blue-colored sky. Additionally, in the rollercoaster scene, the wheel of the cart catches on fire, with yellow-orange flames.

The Handschiegl process enhanced the blue-colored night scene on the rooftop of the Paris Opera, with the Phantom wearing a vivid red cloak, which flutters in the wind.

The Handschiegl process enhanced the blue-colored night scene on the rooftop of the Paris Opera, with the Phantom wearing a vivid red cloak, which flutters in the wind.

The Handschiegl-colored segments occurred in reels three and four: in the yellow-orange coloring for the Pillar of Fire; and the blue water, during the division of the Red Sea.

The Handschiegl-colored segments occurred in reels three and four: in the yellow-orange coloring for the Pillar of Fire; and the blue water, during the division of the Red Sea.

Yellow-orange spot coloring of gunfire, as well as the flames and the smoke of crashing fighter planes, throughout the film.

Yellow-orange spot coloring of gunfire, as well as the flames and the smoke of crashing fighter planes, throughout the film.

Technology

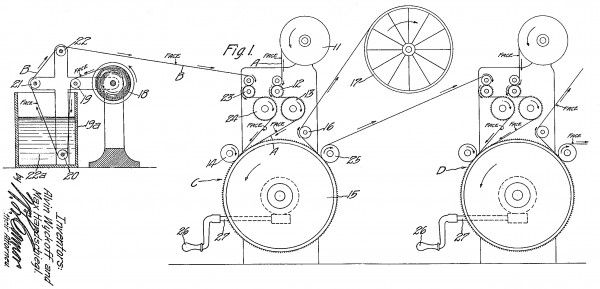

The Handschiegl process was a multicolored, applied color film technology, based on the combination of hand-painted mattes and an imbibition technique (the transfer of a dye from one surface to another). Accordingly, it was a hybrid of manual and mechanized processes that relied on the artistry of Max Handschiegl to handpaint the mattes –while also benefiting from an automatic printing process, which allowed the carefully created mattes to be used to generate multiple film prints.

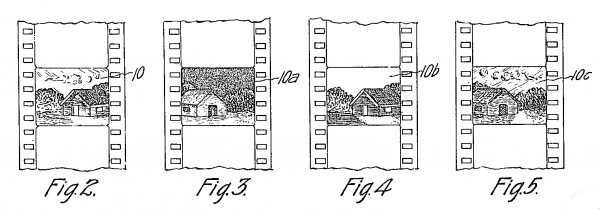

In the first step, for each color that was to be used in the film, a separate matte was prepared by Max Handschiegl on the basis of B/W positive prints. The image areas to be colored were painted manually and frame by frame with the help of a fine brush and a masking lacquer. This step required great attention to detail due to the small size of the frame and to ensure consistency across frames. Kelley (1926: p. 241) even mentions the use of a scalpel for etching.

After making a duplicate negative, in which the blocked-out areas from the coated master positive became transparent and turned into soft gelatin matter, the remaining gelatin was hardened in the exposed areas with a tanning bleach process, in which the silver image was removed. In a further step, the bleached and fixed matrix film was immersed in a dye bath, absorbing the color on the viscous surface of the clear image areas.

During the dye-transfer process, the acid dyes were transferred from the dyed matrices, one after the other, onto a B/W positive print. This was done by means of accurate registering and direct contact pressure on a large sprocket drum with soft rubber rollers for the length of time required for the positive to be able to absorb the dyes. Using more than one color required a series of the machines to be aligned and used in sequence.

The system of color transfer and imbibition was derived from the planographic printing method chromolithography, which had gained popularity toward the end of the nineteenth century. Within the field of early color animation techniques in cinema, lithographic films for toy lanterns and projectors used a similar lithographic system on celluloid before Kelley Color and Technicolor #3 and #4 continued the same basic principle.

Wyckoff and Handschiegl’s 1919 patent, US1,303,836, indicates that the coloring system was adapted for the application of the primary colors red, yellow and blue to a positive film, in theory allowing any desired hue to be produced. Accordingly, the Handschiegl process, at least in theory, was envisioned as a subtractive three-color printing process, whose dyes were used similarly to lithographic printing inks (Read, 2009: p. 37). Ultimately, this would suggest another difference to stencil color, where a large palette of different synthetic dyes were required, depending on the desired result. However, it begs the question, whether the Handschiegl process was actually used in practice as a true subtractive color process, as it rarely seems that more than one or two colors were used and, significantly, productions mainly resorted to the practice of spot coloring.

The Handschiegl process produced aesthetically pleasing, atmospheric, color effects that adhered to the contemporary fashion for pastel coloring. For instance, Moving Picture World (February 9, 1918: p. 832) reported: “This process does not give glaring and noticeable colors to the films, but softens and subdues the coloring of scenes to an almost pastelle [sic] effect.” In fact, it is likely that Handschiegl’s creation of subtle graduations of color contributed to its commercial success. Yet, its achievement was very likely also due to the fact that the process could be used for B/W film productions already completed and could be projected with standard equipment, which was a major advantage in contrast to the many, more complex and impractical additive systems.

The dye-transfer printing machine. The dye was transferred from the dyed matrix film to the B/W print, while being held in contact over a large rotating drum.

Wyckoff, Alvin & Max Handschiegl (1919). Art of Coloring Cinematographic Films. US Patent US1,303,836, filed November 20, 1916, and issued May 13, 1919.

Technical diagram of the hand-painting and dyeing process: B/W source negative (Fig. 2); B/W print made from the negative, with the sky hand-painted with a lacquer impervious to light (Fig. 3); B/W duplicate negative where the sky area is now unexposed soft gelatin, capable of absorbing dye (Fig. 4); and the final B/W print, with blue sky after the matrix has been pressed into contact with the print to transfer the dye (Fig. 5).

Wyckoff, Alvin & Max Handschiegl (1919). Art of Coloring Cinematographic Films. US Patent US1,303,836, filed November 20, 1916, and issued May 13, 1919.

Left: 35mm B/W Handschiegl matrix film of a gold nugget for Greed (1924), before bleaching.

Right: Bleached and dyed 35mm matrix of a close-up of two orange-colored canaries in a gold cage, in Greed.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Natural History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

The dazzling, gold effect of a large Handschiegl-colored tooth in Greed (1924), achieved by combining yellow and orange dyes in conjunction with the crisp silver image behind.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Natural History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

Poor Men’s Wives (1923) used at least three colors for this elaborate intertitle. The yellow and blue matrix films before dyeing appear above (the red matrix film is missing), with the fully colored frame, below.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Natural History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

References

Anon. (1918). “Lasky Chiefs Working on Color Process”. The Moving Picture World, 35:6 (February): p. 832.

Anon. (1920). “Claim Process Rights”. The Film Daily, 13:75 (September): p. 1.

Anon, (1926). “Color Firms Merge”. The Film Daily, 38:77 (December): pp. 1–2.

Anon. (1928). “Max Handschiegl”. Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 12:34 (April): p. 574.

Cherchi Usai, Paolo (2019). Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship. London: British Film Institute.

DeMille, Cecil B. (1959). The Autobiography of Cecil B. DeMille (Donald Hayne, ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Harleman, G. P. (1918). “Lasky Picture Plant Suffers in Spectacular Studio Fire”. The Moving Picture World, 36:8 (May): p. 1145.

Kelley, William Van Doren (1926). “Imbibition Coloring of Motion Picture Films”. Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 10:28: pp. 238–41. https://doi.org/10.5594/J00873.

Kelley, William Van Doren (1931). “The Handschiegl and Pathéchrome Color Process”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 19:2: pp. 230–34.

Koszarski, Richard (1999). “Reconstructing GREED How Long, and What Color?”. Film Comment, 35:6: pp. 10–15.

Read, Paul (2009). “‘Unnatural Colours’: An Introduction to Colouring Techniques in Silent Era Movies”. Film History, 21:1): pp. 9‒46.

Sanborn Laboratories Inc. (1918). “Sanborn Laboratories Inc.” (advertisement). The Moving Picture World, 35:8 (February): p. 1149.

Special Pictures Corporation (1918). “Comedies: A Comedyart Production; Now Let’s Show You” (advertisement). Motion Picture News, 21:10 (February): p. 2085.

Theisen, W. E. (1935). “William Van Doren Kelley (1876–1934)”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 24:3 (March): pp. 275–77.

Patents

Handschiegl, Max. 1919. Cinematographic-Film-Coloring Machine. US Patent US1,295,028, filed April 30, 1918, and issued February 18, 1919.

Handschiegl, Max. 1919. Process of Producing Colored Moving Picture Films. US Patent US1,316,791, filed April 9, 1918, and issued September 23, 1919.

Wyckoff, Alvin and Max Handschiegl. 1919. Art of Coloring Cinematographic Films. US Patent US1,303,836, filed November 20, 1916, and issued May 13, 1919.

Wyckoff, Alvin and Max Handschiegl. 1919. Machine for and Art of Coloring Cinematographic Films. US Patent US1,303,837, filed November 20, 1916, and issued May 13, 1919.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Olivia Kristina Stutz is a PhD student in the University of Zurich’s Department of Film Studies, with a particular affiliation to the ERC Advanced Grant FilmColors project. Her research focuses on the relationship between the technology and aesthetics of color film processes in the period from the mid-1890s to the early 1930s, with a special interest in the materiality of both the analog film and the profilmic setup. She was an active contributor to and curator of the Timeline of Historical Film Colors from 2016 to 2020 and acquired experience with nitrate film during stints in the Silent Film Department at the BFI National Archive (UK) in 2016 and in the Department of Film Conversation and Digital Access at the EYE Filmmuseum (NL) in 2017. More recently, she contributed to the film exhibition Color Mania: The Material of Color in Photography and Film (2019) at Fotomuseum Winterthur (CH). Her published essays include “Such (Dye-)Stuff as Dreams Are Made On: Material Interactions between the Photography, Film, and Fashion Industries” (2020) and “The Hybrid Color Film: Multiplicity of Space, Time, and Matter” (2021).

I thank Barbara Flückiger for supporting my participation in the Film Atlas project, and James Layton for providing me with extensive source material and engaging in lively exchanges about the differences between the Handschiegl and Quadricolor processes.

Stutz, Olivia Kristina (2024). “Handschiegl”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.