A manually applied color process developed in the 1890s as a means of adding color to a B/W film print by hand, with a brush.

Film Explorer

An early hand-colored 35mm print of Serpentine Dance (1896), by C. Francis Jenkins, most likely for use on his “Phantoscope” projector.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

35mm print of Automaboulisme et Autorité (Georges Méliès, 1899). Many of Méliès’ playful trick films were elaborately hand colored.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

A 35mm print of the feature film Fighting the Flames (B. Reeves Eason, 1925). This thrilling sequence was tinted red and then further embellished with orange hand-colored flames by Arnold Hansen.

National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, United States.

A 16mm print of Fernand Léger’s Ballet mécanique (1924), hand colored by Gustav Brock for The Museum of Modern Art, in the 1930s.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

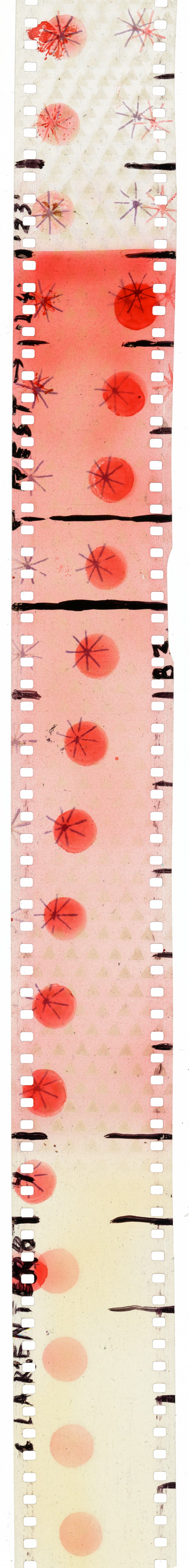

A 35mm hand-colored and stenciled original by Len Lye, conserved in a film can labeled: “35mm painted original. It is a sample of my experiments with lacquer paint on celluloid animation.” The material probably formed part of Lye’s experiments for some of his abstract animation works from the 1930s, such as Colour Box (1935) and Colour Flight (1937).

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Identification

35mm primarily, 16mm (used on most gauges).

B/W, at times combined with tinting, toning and/or stenciling. The hand-coloring dye was absorbed into the gelatin emulsion, laying the color on top of the B/W image.

Any B/W print stock could be hand colored, and as such, a wide variety of film stock manufacturer markings can be found on hand-colored prints.

1

Color applied to positive film prints by brush. The accuracy varied widely, as did the stylistic effects. Hand coloring could call attention to specific details in the frame (such as a detail of an outfit), or could be used to enhance explosion or fire effects. It was difficult to maintain precision across multiple frames – fringing effects around the edge of objects are common.

B/W (typically).

History

Hand coloring was the original method for applying color to film. At times, such coloring added a naturalistic element to the image – for instance, adding blue to skies and rivers, greens to vegetation, or browns to outfits. In other instances, it was added to create dazzling effects, particularly in trick and fairy films – where hand-colored reds and oranges were often keyed to flames and explosions – and an array of vivid hues might be applied to resplendent costumes. Beginning in the mid-1890s, the meticulous hand-coloring work was most often carried out by teams of highly skilled, female colorists – the process was extraordinarily labor intensive, as colors had to be applied frame-by-frame on each and every projection print. One film-coloring workshop in Paris, founded by Élisabeth Thuillier (1841–1907) and carried on by her daughter Berthe Thuillier (1867–1947), reportedly employed upwards of 220 female colorists at its height (Salmon & Malthête, 2013). Bertha Thuillier recalled in a 1929 interview that: “I colored all of Méliès’ films, and this work was carried out entirely by hand. I employed two hundred and twenty workers in my workshop. I spent my nights selecting and sampling the colors, and during the day; the workers applied the color according to my instructions. Each specialized worker applied only one color, and we often exceeded twenty colors on a film” (quoted in Yumibe, 2013).

The first hand-colored pictures were dance films. At the time, female dance routines by popular vaudeville performers such as Loïe Fuller (1862–1928) and Annabelle Moore (née Whitford) (1878–1961). Theater technicians often projected shifting, colored lighting effects onto the performers as they moved about the stage – early filmmakers aimed to replicate these effects using hand coloring. Early cinema pioneer C. Francis Jenkins reportedly first exhibited a hand-colored print in Richmond, Indiana, on June 6, 1894, on his Phantoscope device. According to author and screenwriter Homer Croy, writing in 1918, the screening featured a butterfly dance by Annabelle Moore that had been colored by a Mrs. Boyce of Washington, DC, who was also a lantern-slide colorist (Croy, 1918: p. 42). From around 1895, Edison Kinetoscope films were also being colored, notably those featuring Moore performing serpentine dances, such as Annabelle Serpentine Dance [No. 2] (1895), as preserved at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Selective hand coloring is used on the print for specific objects: Annabelle’s orange hair; the pink of her arms and upper chest; and her prismatic dress, which changes in hue from yellow to purple to peach, as she swirls her billowing skirts about her. Such coloring provided a sensual quality, rendering moving images almost tactile – nearly stereoscopic, according to reports from the time. A 1896 brochure for Edison films, from the early cinema distributors Raff and Gammon boasted: “With the life tint upon face, hands, arms and other features, and with vivid coloring of costume and accessory, the subjects stand out from the canvas like living men and women, and the effect is so vivid and so remarkably life-like as to excite the wonder and enthusiastic comment of all beholders.” (Raff & Gammon, 1896: p. a–021). Given the swirling, diaphanous subjects of many of these early dance films, the frame-to-frame precision of hand coloring was relatively less critical. When these films were projected, the hues would pulse over and around the selected objects, adding to the abstract attraction of these works.

Early non-fiction works were also quite often hand colored, such as a print of Auguste and Louis Lumière’s Les Forgerons (1895), preserved by Lobster Films, in which two laborers work a forge and anvil, with blue hand coloring used for sections of their outfits, and orange used for the fire in the forge and the red-hot iron rod being worked. Another example is the British Mutoscope and Biograph Syndicate 68mm film, Conway Castle – Panoramic View of Conway on the L. & N.W. Railway (1898), which provides a spectacular phantom ride shot in northern Wales, with the landscape colored green, the bricks of the castle and various walls in a brownish-tan, and a few items in red and blue – a railway sign, a roof, a poster. For works such as these, precision in coloring was important, though difficult to achieve, as variation in the application of color from frame to frame would result in fringing effects when projected. As with many hand-colored films, it is uncertain who actually applied the color to this film. Mutoscope and Biograph could have had the print colored, though often with silent films from this era, exhibitors, rather than producers, often commissioned the coloring work for the prints that they owned.

Hand coloring also contributed immensely to the popularity of trick and fairy films towards the late 1800s. These genres derived from nineteenth-century stage traditions and emphasized spectacular displays of wonder: appearances and disappearances, inanimate objects brought to life, crashes, explosions, diabolical tricks and fairy magic. Vivid applied hues heightened these wonders. For instance, in George Méliès’s Le dirigeable fantastique (1906), which was probably colored in Thuillier’s lab, a zeppelin airship ignites in orange-red flames, tinged with pink and yellow, as it floats across a night-blue sky.

Due to the intensive labor required, hand coloring became an increasingly artisanal procedure, only used for selected films, and selected scenes, from the middle of the first decade of the 1900s on. Other, more industrially scalable coloring techniques, such as tinting, toning and stenciling, increasingly supplanted hand coloring, without quite eliminating it entirely. Hand coloring persisted well into the twentieth century as a small, but dazzling, part of moving-image culture: from Gustav Brock’s work on silent and sound films in the 1920s and 1930s, such as The Death Kiss (1932), to Jacques Tati’s addition of hand-colored elements to the 1964 re-edit of Jour de fête (1949). But, perhaps more significantly, hand coloring played an important role in the work of various experimental filmmakers, such as Len Lye, Margaret Tait, Stan Brakhage and, more recently, Jodie Mack – often in tandem with abstract animation and reversal and optical printing effects.

Selected Filmography

Beginning in the mid-1890s, serpentine dance films were some of the earliest and most popular films to be hand colored, for Edison’s Kinetoscope as well as for C. Francis Jenkins’s exhibitions. In the case of Annabelle Dances, the color adds another layer of abstraction to the remarkable movements of the dancer and her screen-like robes. Preserved by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Beginning in the mid-1890s, serpentine dance films were some of the earliest and most popular films to be hand colored, for Edison’s Kinetoscope as well as for C. Francis Jenkins’s exhibitions. In the case of Annabelle Dances, the color adds another layer of abstraction to the remarkable movements of the dancer and her screen-like robes. Preserved by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Produced using Demeny’s camera for Gaumont, this early hand-colored film was used as part of a multimedia, live fairy play staged at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. The dazzling colors would have aligned with the stage-lighting effects and the costumes of the live performance. Preserved by the Gaumont-Pathé Archives, Paris.

Produced using Demeny’s camera for Gaumont, this early hand-colored film was used as part of a multimedia, live fairy play staged at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. The dazzling colors would have aligned with the stage-lighting effects and the costumes of the live performance. Preserved by the Gaumont-Pathé Archives, Paris.

In one of the earliest, surviving Méliès films to be hand colored, a nobleman’s garments are colored a heavily saturated, pinkish red. The color here works to isolate the main character from the background, drawing attention to him. Importantly, the hand coloring not only amplifies the film’s trick attractions, but also distracts the viewers’ eyes in a sleight of hand, rendering the substitution splices relatively invisible. Preserved by Lobster Films, Paris.

In one of the earliest, surviving Méliès films to be hand colored, a nobleman’s garments are colored a heavily saturated, pinkish red. The color here works to isolate the main character from the background, drawing attention to him. Importantly, the hand coloring not only amplifies the film’s trick attractions, but also distracts the viewers’ eyes in a sleight of hand, rendering the substitution splices relatively invisible. Preserved by Lobster Films, Paris.

For this promotional film for the British GPO Film Unit, Lye hand colored and stenciled abstract, rhythmic hues across a blank film strip, which was subsequently printed onto more muted Dufaycolor reversal stock. The original hand-colored nitrate still exists and was reprinted by the BFI’s João S. de Oliveira in the late 1990s onto a more saturated Eastman Color stock. Preserved by the BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom.

For this promotional film for the British GPO Film Unit, Lye hand colored and stenciled abstract, rhythmic hues across a blank film strip, which was subsequently printed onto more muted Dufaycolor reversal stock. The original hand-colored nitrate still exists and was reprinted by the BFI’s João S. de Oliveira in the late 1990s onto a more saturated Eastman Color stock. Preserved by the BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom.

Also produced on large-format 68mm, hand coloring is applied onto this mesmerizing phantom ride that passes through Conwy Castle in northern Wales. Preserved by Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Also produced on large-format 68mm, hand coloring is applied onto this mesmerizing phantom ride that passes through Conwy Castle in northern Wales. Preserved by Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Six years in the making, Brakhage created this hand-colored masterpiece by painting and drawing over a variety of recycled material in various formats, including IMAX, 70mm and 35mm. It was re-photographed by Dan Yanosky of Western Cine. Preserved by the Academy Film Archive, Hollywood, CA.

Six years in the making, Brakhage created this hand-colored masterpiece by painting and drawing over a variety of recycled material in various formats, including IMAX, 70mm and 35mm. It was re-photographed by Dan Yanosky of Western Cine. Preserved by the Academy Film Archive, Hollywood, CA.

Gustav Brock, originally a miniature watercolorist with Danish roots, hand-colored release prints of this film, specifically focusing on a dynamic scene early on, when a film print catches fire in a studio theater screening dailies. When the print ignites, orange hand-colored flames erupt on the screen. Brock reportedly single-handedly colored all the release prints of the film. Preserved by the Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA.

Gustav Brock, originally a miniature watercolorist with Danish roots, hand-colored release prints of this film, specifically focusing on a dynamic scene early on, when a film print catches fire in a studio theater screening dailies. When the print ignites, orange hand-colored flames erupt on the screen. Brock reportedly single-handedly colored all the release prints of the film. Preserved by the Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA.

Most likely colored in the Thuillier lab, the film is full of detailed hand-coloring work, with various costumes in reds, yellows and blues. Its most colorful moments come with the pyrotechnic explosion of the airship, which erupts to fill the screen in a shifting mix of reds, oranges, yellows and purples. Preserved by Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Most likely colored in the Thuillier lab, the film is full of detailed hand-coloring work, with various costumes in reds, yellows and blues. Its most colorful moments come with the pyrotechnic explosion of the airship, which erupts to fill the screen in a shifting mix of reds, oranges, yellows and purples. Preserved by Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Full of remarkable hand-colored details, throughout the mise-en-scène – such as costumes, stormy skies and magical fauna – this fairy film becomes like an animated, illuminated manuscript. Preserved by the Cinémathèque française, Paris.

Full of remarkable hand-colored details, throughout the mise-en-scène – such as costumes, stormy skies and magical fauna – this fairy film becomes like an animated, illuminated manuscript. Preserved by the Cinémathèque française, Paris.

A collaboration with the electronic artist Four Tet, this 16mm direct animation work deploys a range of abstract hues through hand coloring and stenciling effects.

A collaboration with the electronic artist Four Tet, this 16mm direct animation work deploys a range of abstract hues through hand coloring and stenciling effects.

Amongst Scottish filmmaker Margaret Tait’s many remarkable works are three hand-painted, abstract animations, including this one, in which abstract colors dance in a variety of joyous patterns to the song, of the same title, played by the Orkney Strathspey and Reel Society. Preserved by the National Library of Scotland – Moving Image Archive, Glasgow. https://movingimage.nls.uk/film/4445

Amongst Scottish filmmaker Margaret Tait’s many remarkable works are three hand-painted, abstract animations, including this one, in which abstract colors dance in a variety of joyous patterns to the song, of the same title, played by the Orkney Strathspey and Reel Society. Preserved by the National Library of Scotland – Moving Image Archive, Glasgow. https://movingimage.nls.uk/film/4445

Produced in large-format 68mm, hand coloring is used to amplify the joyous movement of this can-can performance by a group of young dancers. Against the black background, any misapplication of color is hidden from the viewer. Preserved by Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Produced in large-format 68mm, hand coloring is used to amplify the joyous movement of this can-can performance by a group of young dancers. Against the black background, any misapplication of color is hidden from the viewer. Preserved by Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

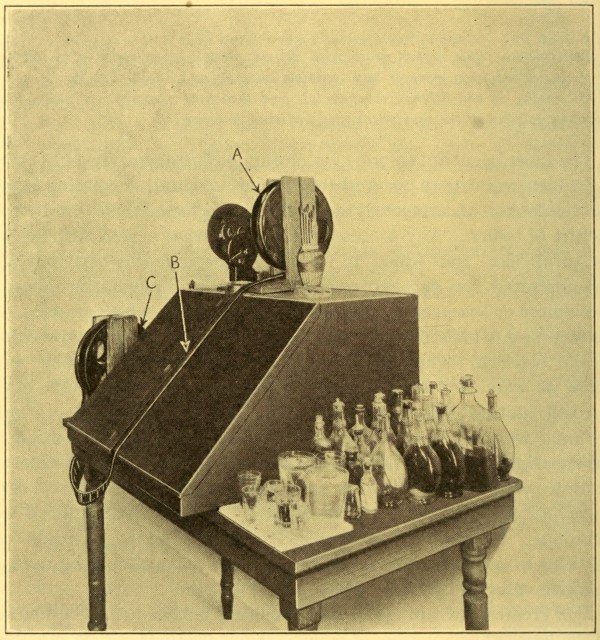

Technology

Hand coloring is an arduous handicraft process requiring frame-by-frame precision by colorists working with tiny brushes (at times as small as a single camel hair bristle for detail work), translucent dyes and magnifying glasses. These tools and the labor practices involved were adapted in the 1890s most directly from the lantern slide and photography industries, which employed coloring firms to hand color their works. Indeed, many of the early colorists working on film began in these other industries and often carried out work simultaneously across them. This was the case with Élisabeth and Berthe Thuillier, who were established colorists of photography, glass slides and other media, when cinema emerged – they added film coloring to the list of services they offered, working on films for Star Films, Pathé and others. For smaller projects, a single colorist might carry out all of the coloring on a film print, but, as with the Thuilliers’ workshop, with larger print runs the labor could also be divided among a coordinated team of colorists, with each team-member working with a specific color.

Because each hand-colored print had to be created individually during the silent era, no two copies were colored in exactly the same way. Some versions of the same film might be in B/W, while other prints might be hand colored to varying degrees. In some cases, colorists filled in entire frames. More often, they painted only particular elements – a scarlet dress, golden coins, red-orange lava erupting from volcanoes, or fountains glittering in pinks, yellows and golds. Variations were common. In one frame, dye might spill from a woman’s costume across an arm or a leg. In another frame, a yellow face might revert to B/W, or a brush stroke might easily slip outside its edges. Although each individual error was almost imperceptible as such when projected, together they created characteristic, ephemeral, flickers of color.

Given its labor-intensive nature, hand coloring was costly – if there was a choice of colored or monochrome prints, exhibitors would pay a premium for the hand-colored versions. Based on advertised prices, at the turn of the nineteenth century hand coloring could add between 30 and 50 percent to the cost of a print (Yumibe, 2012: p. 51). The artisanal quality of hand coloring was popular with audiences, but as the early 1900s progressed and firms such as Pathé were seeking to expand rapidly, the industry began to develop machine-stenciling processes that replicated many of the effects of hand coloring, but at a much lower cost, particularly on larger print runs. In later experimental practices, handicraft techniques persisted. Filmmakers such as Len Lye took advantage of new color processes that became available in the 1930s, including Dufaycolor and Gasparcolor, to duplicate his hand-coloring work. Duplication became easier in the post-World War II era, when internegative duplicating stocks became widely available. Stan Brakhage used internegative duplication extensively in in his hand-colored films, working collaboratively through a hybrid mix of hand-colored originals, which were subsequently refined through optical printing in the lab (Toscano, 2012).

References

Brock, Gustav (1931). “Hand-Coloring of Motion Picture Film.” Journal of the SMPE, 16: 6 (June): pp. 751–755. Available at https://archive.org/details/journalofsociety16socirich/page/752/mode/2up

Cherchi Usai, Paolo (2019). Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship (3rd edn). London: BFI/Bloomsbury.

Croy , Homer (1918). How Motion Pictures Are Made. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Fossati, Giovanna, Tom Gunning, Jonathon Rosen & Joshua Yumibe (2015). Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Fossati, Giovanna, Vicky Jackson, Bregt Lameris, Elif Rongen-Kaynakçi, Sarah Street & Joshua Yumibe (eds) (2018). The Colour Fantastic: Chromatic Worlds of Silent Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Gunning, Tom (2003). “Colourful Metaphors: The Attraction of Colour in Early Silent Cinema”. Living Pictures: The Journal of the Popular and Projected Image before 1914, 2: 2 (Special Issue: Colour): pp. 4–13.

Hertogs, Daan & Nico de Klerk (eds) (1996). “Disorderly Order”: Colours in Silent Film – the 1995 Amsterdam Workshop. Amsterdam: Stichting Nederlands Film Museum.

Jenkins, Charles Francis (1898). Animated Pictures. Washington, DC: Press of H. L. McQueen.

Mazzanti, Nicola (2009). “Colors, Audiences, and (Dis)continuity in the ‘Cinema of the Second Period’”. Film History, 21:1 (Special Issue on Color): pp. 67–93.

Raff & Gammon (1896). “The Vitascope” (Brochure, March). In Charles Musser (ed.), Motion Picture Catalogs by American Producers and Distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition. Frederick, MD: University Publications of America, 1984–1985, pp. A-009–022.

Read, Paul (2009). “‘Unnatural Colours’: An Introduction to Colouring Techniques in Silent Era Movies”. Film History: An International Journal, 21:1: pp. 9–46.

Salmon, Stephanie & Jacques Malthête (2013). “Élisabeth and Berthe Thuillier” In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal & Monica Dall’Asta (eds), Women Film Pioneers Project. New York: Columbia University Libraries, Center for Digital Research and Scholarship. Available at https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/elisabeth-and-berthe-thuillier.

Street, Sarah & Joshua Yumibe (2019). Chromatic Modernity: Color, Cinema, and Media of the 1920s. New York: Columbia University Press.

Toscano, Mark (2012). “Stan Brakhage’s Two Negatives”. Preservation Insanity (Feb. 24). https://preservationinsanity.wordpress.com/2012/02/24/stan-brakhages-two-negatives/ (accessed Mar. 6, 2025)

Yumibe, Joshua (2012). Moving Color: Early Film, Mass Culture, Modernism. Techniques of the Moving Image. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Yumibe, Joshua (2013). “French Film Colorists”. In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal & Monica Dall’Asta (eds). Women Film Pioneers Project. New York: Columbia University Libraries, Center for Digital Research and Scholarship. Available at https://wfpp.columbia.edu/essay/french-film-colorists.

Patents

Compare

Related entries

Author

Joshua Yumibe is professor of film studies at Michigan State University. He is the author of Moving Color: Early Film, Mass Culture, Modernism (Rutgers University Press, 2012), co-author, with Giovanna Fossati, Tom Gunning and Jonathon Rosen, of Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema (Amsterdam University Press, 2015), and most recently, with Sarah Street, Chromatic Modernity: Color, Cinema, and Media of the 1920s (Columbia University Press, 2019). He is also an editor of Screen and of the Contemporary Film Directors at the University of Illinois Press.

Material for this entry is adapted primarily from Moving Color: Early Film, Mass Culture, Modernism (2012) and “Techniques of the Fantastic”, in Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema (2015).

Yumibe, Joshua (2025). “Hand Coloring”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.