Non-photographic film strips printed with a lithographic system in color or B/W, projected on toy hybrid lanterns or toy projectors. They were usually joined into continuous loops.

Film Explorer

The Serpentine Dancer (c. 1900). (found in the Bing catalogue 1906-07) is the most well known lithographic film strip; multiple versions with different coloring exist. This example shows a rich palette of red, green, blue, light blue, yellow, light orange, and black ink. The recreation of the luminous projected colors on the dancer’s butterfly dress were initially painted by hand on the source live action films, then these drawn images were recreated by a chromolithographic printing system.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

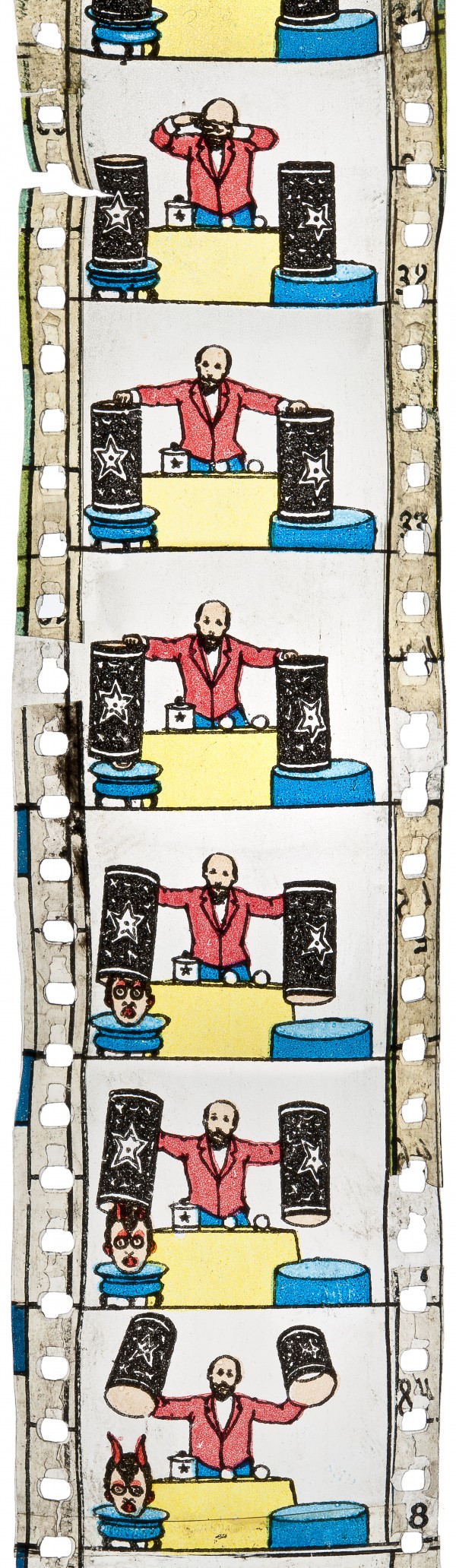

A 35mm lithographic print of the Georges Méliès film Une séance de prestidigitation (1896). This copy is extremely fragile and warped.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

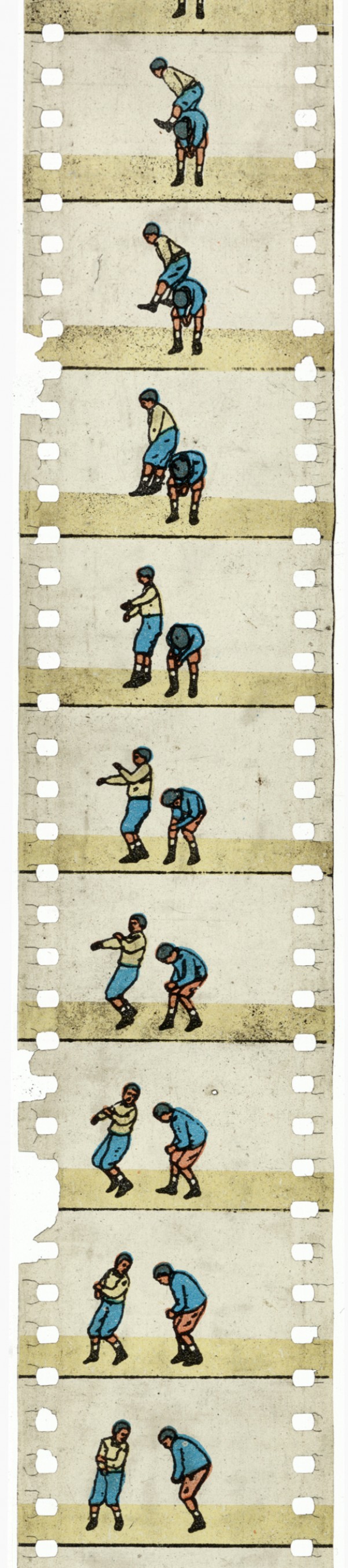

Unidentified film (c. 1900).

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

Identification

Close to full silent aperture for the vertical system. For the horizontal running system, the dimension varies.

The images are made of black and/or colored dyes printed onto a blank strip of film via lithographic printing. Some are embellished with hand painting.

There are different edge markings depending on the manufacturer, and/or numbers. Some films have no identification marks.

Most commonly cellulose nitrate, possibly cellulose diacetate in some cases.

1

This was not a natural color process. The images were applied via lithographic printing in B/W, or using two colors, or multiple colors.

No on-screen credits. Distributor names are sometimes marked on the film’s edges.

History

Lithographic films were short loops of film designed for toy magic lantern projectors for home or family use. They emerged not long after the first attempts to project moving images, such as Émile Reynaud’s “Théâtre optique” (1894) and the Cinématographe by the Lumière brothers (1895). These short film loops were, at the time, called either Cinematographs or Kinematographs and were sold in toy catalogues at the end of the nineteenth century. They were a cross between magic lanterns and cinematographs, but were intended for home use instead of theatrical projection.

These toy lanterns were first manufactured by the French August Lapierre in 1843. At that time, Nuremberg in Germany was already the world center of toy manufacturing. This city soon became a hub for the manufacture of toy lanterns as well. The Ignaz and Adolf Bing company (trademark GBN) started the production of toy lanterns, including hybrid models where slides and film could be projected on a single lantern. In Germany, Ernst Plank also became a major producer of magic lanterns, as did Georges Carette in France – whose lanterns were copied from the Lapierre models. These manufacturers invented models of hybrid magic lanterns, able to screen both slides and films by superimposition during projection. The slide could be used as a background for the moving image and a panoramic image could be moved horizontally while the film was projected.

The earliest hybrid lanterns dealt quite often with short sequences of movement that were repeated (cavalry, sport, dance, animal motion). But quickly the big “hits” of the theaters, such as magicians, serpentine dancers, trick films and scenes featuring children and famous acrobats started to appear in these films.

Many films for toy lanterns were precise replicas of existing live-action silent films. We don’t know how copyrights were cleared by the lithographic film manufacturers, but it seems the films were likely pirated. Scenes originally made by Méliès, Lumière, Pathé and Gaumont appear in modified form for the toy projector versions. We find different kinds of scenes, generally 30 or 60 frames long, but they can also be 120 frames or longer. Some of the loops were sold in both versions – long or short – at different prices. For the films distributed as loops, the first frame of a short film was spliced to its last frame to create a continuous loop of the film in projection. When the loop was mounted in the toy lantern, a crank helped to animate movement and repeat the loop as often as wanted by the lanternist. It was also possible to move the film backward.

These lantern films were among the first animated films. Not all of them were copies of existing films – many were newly produced. For instance, in the mid-1910s and 1920s, the famous illustrator Marius O'Galop designed a dozen so-called “chromo-comic” films for Lapierre (Vignaux, 2009). The “chromo-comic” films of Marius O'Galop illustrate everyday life, but also utilize strange visual effects, such as in a loop where a barber straddles the shoulder of his customer and his foot and the razor change scale and appear disproportionate. He also made two films where a boy draws figures that come to life, evoking Émile Cohl's Fantoche series. Companies such as Bing, also manufactured films for theaters until 1927–28. These latter films were called “Single Strip for non-rotation” (rotation implied the loop movement of the lanterns). In the late 1930s the advent of amateur projectors for the 9.5mm and 8mm formats, limited the use of such toys.

“Original Photo Film” can of lithographic loops from Bing.

Museum of Photography from Vevey, Switzerland. Photo © Cinémathèque suisse.

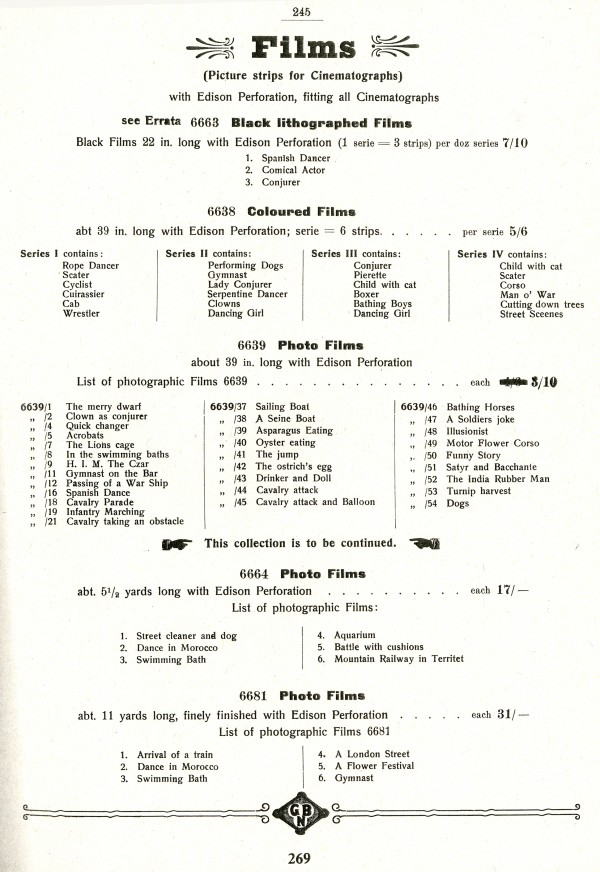

Page from a 1906 British Bing Toy Catalog, listing B/W and colored lithographic films available for purchase.

Spielzeugmuseum Stadt Nürnberg, Nuremberg, Germany.

An original box of a toy magic lantern where the films are already joined together as loops.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

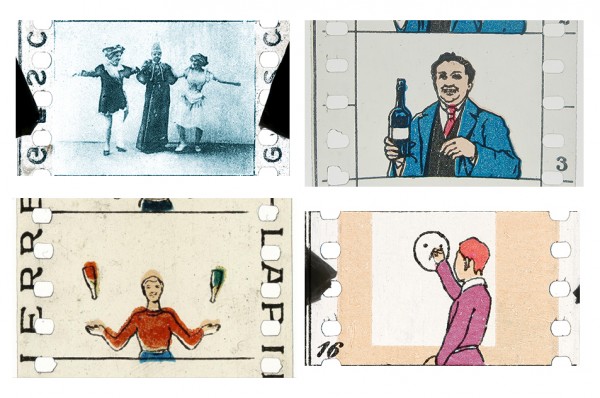

Top left: Unidentified. “Bing Gesch Photo” loop (unknown year). From the collection of the Swiss Camera Museum (Vevey), preserved and restored by Cinémathèque suisse. The numbering system was printed every five frames.

Top right: Unidentified. George Carette and Cie loop (unknown year). From the collection of the Swiss Camera Museum (Vevey), preserved and restored by Cinémathèque suisse. The numbering system was sometimes printed on every frame, or every five frames.

Bottom left: Unidentified. Lapierre-Demaria loop in red, green, blue, light pink and black ink. In 1908, Lapierre joined forces with Demaria, and produced a few films for toy lanterns. The color fringing is more obvious and not as precise as the German manufacturers.

Bottom right: Unidentified, Chromo-comic film of Marius O'Galop. Circa. 1916. The subject evokes the animations of Emile Cohl's Fantoche.

Cinémathèque suisse, Lausanne, Switzerland / Private collector.

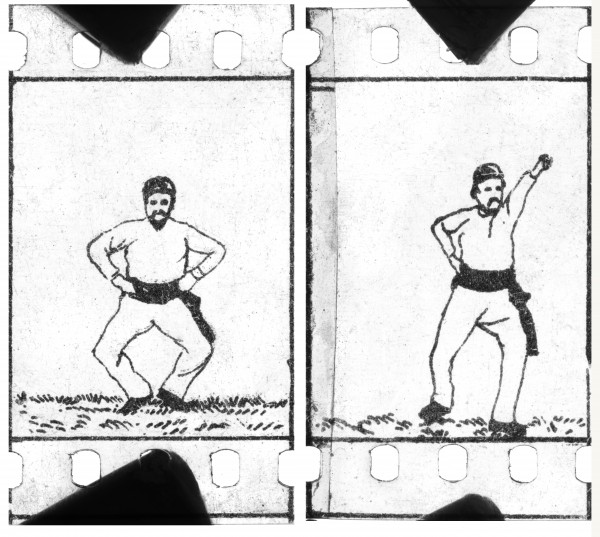

Unidentified, a horizontal chromolithograph film probably used for Bing’s toy lantern “the Kinematograph” manufactured in 1898. This loop uses a black ink. The movement of the characters remind us of the early studies of movements by Étienne-Jules Marey and Georges Demenÿ, who used a horizontal film movement as well.

Collection Cinématheque suisse, Switzerland.

Selected Filmography

Distributed by E. Mazo, 20 or 25m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, 20 or 25m length.

Distributed as The Astronomer in the British Bing catalog, 1902.

Distributed as The Astronomer in the British Bing catalog, 1902.

Distributed by E. Mazo, 20 or 25m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, 20 or 25m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, religious topic, 15 or 20m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, religious topic, 15 or 20m length.

Distributed by Bing.

Distributed by Bing.

Distributed by Bing.

Distributed by Bing.

Distributed by E. Mazo, religious topic, 15 or 20m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, religious topic, 15 or 20m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, 10m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, 10m length.

Distributed by Bing.

Distributed by Bing.

Distributed by E. Mazo, 10m length.

Distributed by E. Mazo, 10m length.

Distributed by Bing from c. 1906-7.

Distributed by Bing from c. 1906-7.

Technology

Lithography is a method of printing first invented in 1796 by the German author and actor Alois Senefelder. A printing stone or metal plate impressed an inked image or text onto the receiving paper. It was initially most commonly used for printing musical scores and maps.

The chromolithographic printing process was an improvement of B/W lithography with the addition of color. It was first patented by Godefroi Engelmann in 1837 and widely used thereafter, although it was hand-pressed at first. Industrial-scale litho machines, or printers, started to be used from the 1850s.

Chromolithography transfers for glass lantern slides first appeared with decalcomania process around the 1860s, and were in wide use from about 1870. Instead of a stone or metal printing plate, the decalcomania printing technique used a porous paper, coated with a solution of starch, albumin and glycerin to transfer colors onto photographic slides. It was a much more economical way to reproduce colors on slides than manual painting with a brush. A toy manufacturer from Nuremberg called Carl Anton Pocher marketed “Metachromotypes” using this technique.

Henry V. Hopwood mentions early inventions patented by Potter and Adams in 1888 using a celluloid strip, where scenes might be painted, or letters stamped out. These systems were designed to move horizontally through an illuminated gate. The Bing catalogue from 1898 (available in German, French and English languages) sold a model called “the Kinematograph” which was a horizontal-running film projector that was reminiscent of Étienne-Jules Marey and Georges Demenÿ’s horizontal 90mm chronophotographic film, designed around 1892. Unidentified horizontal films made for entertainment probably already existed, since they were duplicated in these early loops. Later in 1902 a convertible model called the “Excelsior” could project vertical loops with a mobile film lens, removable during the projection. Vertical loops could also be screened with a slide creating a background. These loops were printed, or lithographed, side-by-side in multiple rows on wide celluloid sheets, which were then cut into loops one by one. This explains the presence of black ink lines on the films. The perforations are irregular too, and were probably made after the first cutting.

The first lithographic films appeared around 1898 in B/W and color, and were printed onto a “nearly” non-flammable strip using a printing system with dyes. The term chromolithography was not used for them at the time – they were most commonly referred to as “litho-films”. These used a printing technique mentioned in the Bing German Patent 345613, filed April 17, 1921:

“The raw material (celluloid) will be lithographed into large plates as is the case with paper. Then the celluloid strips are cut into strips and perforated and glued. Cutting several strips side by side is laborious because the printing blocks have to be specially prepared in order to achieve a relatively smooth print. Therefore, each strip must be created with great precision so that it is not skewed. This is expensive and time-consuming work.”

No other documents or patents have been found detailing the technique used to create the images for lithographic films, so we can only speculate it is connected to decalcomania or to rotoscopy – the technique of tracing live-action movement that was patented in 1917, by the American animator Max Fleischer.

References

Basano, Roberta (1996). “The Magic Lantern as a Toy”. The New Magic Lantern Journal, 8:1 (October): pp. 8-10. https://www.magiclantern.org.uk.

Burch, R. M. (1910). Colour Printing and Colour Printers. New York: The Baker and Taylor.

La Cinémathèque française (n.d.). “Laterna Magica” (accessed January 27, 2023). http://www.laternamagica.fr

La Cinémathèque française (n.d.). “Catalogue des appareils cinématographiques” (accessed January 27, 2023). https://www.cinematheque.fr/fr/catalogues/appareils/a-propos.html

Frutos, Javier-Francisco (2013). “From Luminous Pictures to Transparent Photographs: The Evolution of Techniques for Making Magic Lantern Slides”. The Magic Lantern Gazette 25:3 (Fall): pp. 3–10.

Hecht, Hermann (1980). “Decalcomania: some preliminary investigations into the history of transfer slides”. The New Magic Lantern Journal, 1:3 (March): pp. 3–6.

Herbert, Stephen (1987). “German Home and Toy Magic Lanterns Cinematograph”. The New Magic Lantern Journal, 5:2 (August): pp. 11–15.

Hopwood, Henry V. (1899). “Living Pictures, their history, photoproduction and practical working. With a digest of British patents and annotated bibliography”. The Optician and Photographic Trade Review: pp. 63–65. https://ia600904.us.archive.org/8/items/livingpicturesth00hopw/livingpicturesth00hopw.pdf

Lange-Fuchs, Hauke (1998). “Nuremberg Magic Lantern Production”. The New Magic Lantern Journal, 8:3 (December): pp. 6–13.

The Magic Lantern Society (n.d.). “Lucerna” (accessed January 27, 2023). https://lucerna.exeter.ac.uk

Mannoni, Laurent (1990). “Plaque de verre ou celluloïd? Lanterne magique et cinéma: la guerre d'Indépendance”. 1895, revue d'histoire du cinéma, 7: pp. 3–27.

Mebold, Anke (2016). “German Chromolithographic Loops”. Le giornate del cinema muto, 35, catalogue. (Pordenone film festival October 1–8): pp. 215–221.

Remise, Jack, Remise, Pascale & Van de Walle, Regis (1979). Magie Lumineuse, du théâtre d’ombre à la lanterne magique. France: Balland.

Robinson, David, Herbert, Stephen & Crangle, Richard (2001). Encyclopedia of the Magic Lantern, London: The Magic Lantern Society.

Vignaux, Valérie (2009). “Les images projetées de Marius O’Galop et Robert Lortac: Marius O’Galop / Robert Lortac. Deux pionniers du cinéma d'animation français”. 1895, revue d'histoire du cinéma, 59: pp. 46–54.

Weaver, Peter (1964). The Technique of Lithography, p. 49. London: B.T. Batsford.

Patents

Solomons, Samuel. 1865–67. Improvement in Transparent Slides For the Magic Lantern, British Patent 63,437, filed 1865, patented April 2, 1867.

Potter, Edward Tuckerman. 1888. Continuous Lantern Slides Drawn From Upper to Lower Spool by Clockwork Intermittent Gear, British patent, patented October 2, 1888.

Adams, W. P. 1888. Continuous Lantern Slides, British patent 14,171, patented November 19, 1888.

Bing. 1907–1910. Improvement in Toy Cinematographs, German patent 26943 filed in April 1907, patented November 29, 1909. British Patent 26,943, filed November 19, 1910, patented April 20, 1909.

Bing. 1921. Litho-Film, German Patent 345613, filed April 17, 1921, patented December 15, 1921.

Bing 1921. kinobildband mit zwei gegenläufigen Bildreihen (film strip with two sets of images in reverse order), German Patent 338771, filed February 1920, patented July 1921.

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Céline Ruivo is the author of a 2016 PhD dissertation titled The Three-color Technicolor: History of a Process and Challenges of its Restoration, University Paris III la Sorbonne nouvelle. She worked as the head of the film collection of La Cinémathèque française from 2011 to 2020. She is an active member of the technical commission of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). She is now a post-doctoral researcher for the B-Magic project at UCLouvain in Belgium.

Caroline Fournier, after having been in charge of the conservation/restoration sector at Cinematheque suisse, has, since 2018, been Head of the Film Department. She is a member of the Technical Commission of FIAF. She has been working on a project of restoration and identification of film loops for toy magic lanterns since 2014.

The authors would like to thank following for their great contributions: Anke Mebold; Laurent Mannoni; Ulrich Rüdel, Christiane Reuer of the Spielzeugmuseum Stadt Nürnber; Mark Paul Meyer, Annike Kross, and Elif Rongen of the Eye Filmmuseum.

Ruivo, Céline & Caroline Fournier (2024). “Lithographic films for toy lanterns and projectors”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.