A subtractive color process invented by William Van Doren Kelley and Carroll H. Dunning.

Film Explorer

Kesdacolor test footage. Prints were made on double-coated stock from a special two-frame negative that captured colour information through a “line screen”. The green-blue dye has faded from this rare sample mounted in a frame.

National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States.

Identification

Not known: probably standard silent aperture.

Emulsion on both sides of the film (double-coated) with one side dyed red and the other green-blue.

Not known.

1

Two complementary colours composed in one frame with one side being red and the other side being green-blue. The colour on the surviving example is faded, with the almost complete loss of the green-blue image.

Unknown

Not known: probably standard silent aperture.

Two frames simultaneously captured.

B/W, panchromatic.

Not known.

History

Of all the colour processes that were either invented by William Van Doren Kelley or associated with him, Kesdacolor is the most mysterious and the least written about. Almost all contemporary knowledge regarding the details of Kesdacolor come from just two sources. One, a brief history of the company that was contained in Kelley’s obituary, written by W. E. Theisen and published in the Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (March, 1935); the other, the technical specifics of the process, which can be drawn from US patent 1431309A, filed by Kelley and Dunning in 1919.

Theisen states that following the first Prizma film release in 1917, Kelley was not satisfied with the colour achieved and entered into a new partnership with Carroll H. Dunning and Wilson Saulsbury. A laboratory was opened at 205 West 40th Street in New York City, under the name Kesdacolor. The first film made by the Kesdacolor process under the new partnership was a picture of the American flag. At a length of 50 ft, it was shown at the Roxy [sic] and Rialto theatres in New York, on September 12, 1918 (Theisen, 1935).

This statement was copied by Major Adrian Bernard Klein (aka Adrian Cornwell-Clyne) in his book Colour Cinematography, first published in 1936, and later reprinted in 1939 and 1951. Since this book became the ultimate guide for film colour researchers, this short history of Kesdacolor has been copied and quoted by many historians and researchers whose writings touched on this subject.

Although Theisen would have meant Rivoli and Rialto (as the Roxy theatre was not opened until 1927), no record has been found of the screening of the film The American Flag on September 12, 1918 in any of the contemporary motion-picture trade papers. One plausible explanation could be that the American Flag was seen in every theatre, either physically on stage, or on slides and films, as part of the widespread wartime victory celebrations. The film could have been buried in a sea of similar images. There was, however, a similar film made by Douglass Natural Color Films described as the “American Flag in Natural Colors” that was promoted and shown over the same period in 1918 (Anon., 1918b).

Colour film historian Roderick T. Ryan wrote an article about Carroll H. Dunning in 1971, also stating that Dunning joined Kelley and Wilson Saulsbury to form Kesdacolor, and that they made a 100-ft scene of the American flag exhibited simultaneously at the Rialto, Rivoli and Criterion theatres in New York City on September 12, 1918 (Ryan, 1971). The length of the supposed film changed from 50 to 100 ft. However, primary records of the screening, in all three theatres, on the specific date are still lacking.

With the inconsistencies and misinformation in available sources, and the lack of concrete evidence in historical records, the history of Kesdacolor is still shrouded in mystery. However, several facts can be established based on primary sources. First, Kesda, Inc. was incorporated in July 1918 with $50,000, in Manhattan, by H. W. Saulsbury, C. H. Dunning and W. V. D. Kelley, and the address was 1586 East 17th Street, Brooklyn (Anon., 1918a). The name “Kesda” came from the names of Kelley, Saulsbury and Dunning combined (Ryan, 1971). Second, Kelley mentioned “Kesda” was working on a method for producing a film that projected at 16 pictures per second, in November 1918 (Kelley, 1918). This fact increases doubts about the supposed September 1918 screening of the Kesdacolor film. Kesdacolor ceased operations at the end of 1918 when Kelley, Saulsbury and Dunning rejoined Prizma. H. W. Saulsbury went on to become the president of Prizma, Carroll H. Dunning vice president and W. V. D. Kelley technical adviser (Anon., 1919).

H. W. Saulsbury died in May 1923 and Carroll H. Dunning resigned his position at Prizma soon after (Anon., 1923). Dunning moved to California and opened his own laboratory in 1926, specialising in special optical printing effects and later developed the Dunningcolor process in the 1930s. Kelley left Prizma around 1924 and died in 1934. Dunning died in 1975, at the age of 94 – the final of the three founding members of the Kesdacolor (Anon., 1975).

Selected Filmography

A 50- or 100-ft. short that reportedly played at the Rivoli and Rialto theatres in New York City in September 1918.

A 50- or 100-ft. short that reportedly played at the Rivoli and Rialto theatres in New York City in September 1918.

Technology

All of the technical descriptions of the Kesdacolor process come from a single source: the US patent filed on February 10, 1919 by William Van Doren Kelley and Carroll H. Dunning. By this time, Kelley and Dunning were already back with Prizma. However, since this patent is the only one that was filed by the two together, we may consider it a description of the Kesdacolor process.

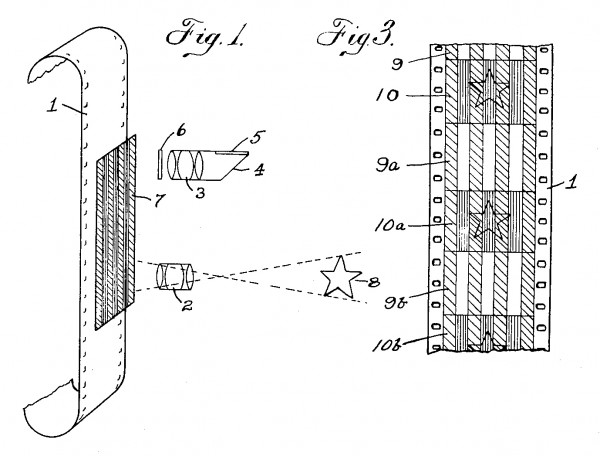

Kesdacolor was a two-colour process. The panchromatic B/W negative ([1] in the diagram) was exposed two adjacent frames at a time through two lenses (2 & 3), both through a line-screen (termed “design screen” in the patent) (7) arranged between the lens and the film, which was composed of vertical lines of red and green colour filters arranged alternately. The pitch of the lines was 1/120th in (0.212mm), which meant about 114 lines per frame. One frame of the negative captured the subject (picture) (8), while the other frame exposed only the line-screen pattern. This line-screen frame was exposed with daylight via a prism (4 and 5) attached to the second lens. This second lens also had an auxiliary colour filter (6) that carried a colour complementary to one of the two colours of the line screen. For example, a colour complementary to the red lines (green-blue), which resulted in recording the green lines only, positioned alternately with the unexposed red lines of the line screen. So, the red line was not recorded on the negative for the line-screen frame

The negative was then developed in the usual B/W negative process. The result was one picture frame (10), with all the colour information of the line screen, and one frame of the line screen (9) with only one colour and one transparent line arranged alternately. Prints were made on double-coated positive film. The printer printed every other frame of the negative onto the positive. The picture frame was printed on one side, and the line-screen frame on the other. The transparent lines became black lines on the positive. And these lines were converted or dyed with a suitable red colour, either by using a uranium salt, or by bleaching and dying red. The green lines were dyed to green-blue by using a dye known as ‘Acid Green L’.

The final print contained pictures with two-colour information on one side and two-colour filters on the other, corresponding to each other, all in the line-screen design. Thus, the positive print obtained colour using subtractive methods. The print could, therefore, be projected on a standard projector at 16 fps.

The patent claimed that the line-screen could potentially allow for any desired number of colours, depending upon the subject. And the line-screen could be designed in squares, lines, or any desired symmetrical arrangement, so long as they were capable of uniform reproduction over the entire surface.

Whether these alternate kinds of line-screen negatives were made or not is still doubtful. One thing is certain though, that the next version of Prizma Color adopted the double-coated positive method for making prints and they could be projected at normal 16 fps (Anon., 1919).

The arrangement for the simultaneous exposure of picture and line-screen, and the negative film produced by this arrangement. (1) panchromatic B/W negative; (2) usual objective lens; (3) second lens; (4) angular mirror; (5) ground glass;(6) auxiliary color filter; (7) design screen (line-screen); (8) the object to be photographed; (9) design areas; (10) picture areas.

Kelley, W. V. D. and Dunning, C. H. Motion Picture Film. US patent US1431309A, filed Feb. 10, 1919, and patented Oct. 10, 1922. https://patents.google.com/patent/US1431309A.

References

Anon. (1918a). “New Incorporations”. New York Times (July 20, 1918): p. 14.

Anon. (1918b). “Douglass Natural Color Films”. Motion Picture News (August 24, 1918): p. 1184.

Anon. (1919). “Prizma to Use Standard Projectors”. Moving Picture World, 39:2 (January 11): p. 190.

Anon. (1923). Motion Picture News (May 19): p. 2361.

Anon. (1975). “Obituaries”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, 84:12 (December): p. 1000.

Anon. (1927). “Achievement”. The Film Daily (March 13): p. 1.

Kelley, William V. D. (1918). “Natural Color Cinematography”. Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 2:7 (November): p. 38–43.

Klein, Adrian Bernard (1936). Colour Cinematography (1st edn). London: Chapman & Hall.

Ryan, Roderick T. (1971). “Biographical Note”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, 80:8 (August): p. 664.

Theisen, Earl (1936). “Notes on the History of Color in Motion Pictures”. International Photographer, 8:5 (June): pp. 8–9, 24.

Theisen, W. E. (1935). “William Van Doren Kelley (1876–1934)”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 24:3 (March): pp. 275–277.

Patents

Kelley, W. V. D. and Dunning, C. H. Motion Picture Film. US patent US1431309A, filed Feb. 10, 1919, and patented Oct. 10, 1922. https://patents.google.com/patent/US1431309A/

Compare

Related entries

Author

Bin Li is a film restorer and analogue colour grader, working at Haghefilm laboratory in the Netherlands since 2014. He specialises in restoring unusual and highly damaged film materials, as well as recreating historical film colours. He was responsible for the restoration and digitisation of two big 68mm Biograph projects from the British Film Institute and the Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. He restored and digitised some of the very unique and damaged Étienne-Jules Marey materials, ranging from 26mm to 90mm, for La Cinémathèque française, Paris. Besides film restoration, Bin Li has also identified hundreds of lost films, including Love, Life and Laughter (1923), one of the BFI’s most wanted “lost films”.

The author would like to thank James Layton and Crystal Kui for providing extra research materials and appropriate illustrations for this entry.

Li, Bin (2024). “Kesdacolor”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.