An additive four-colour process developed by William Van Doren Kelley and Charles Raleigh. The first of several colour processes brought to the market under the Prizma name.

Film Explorer

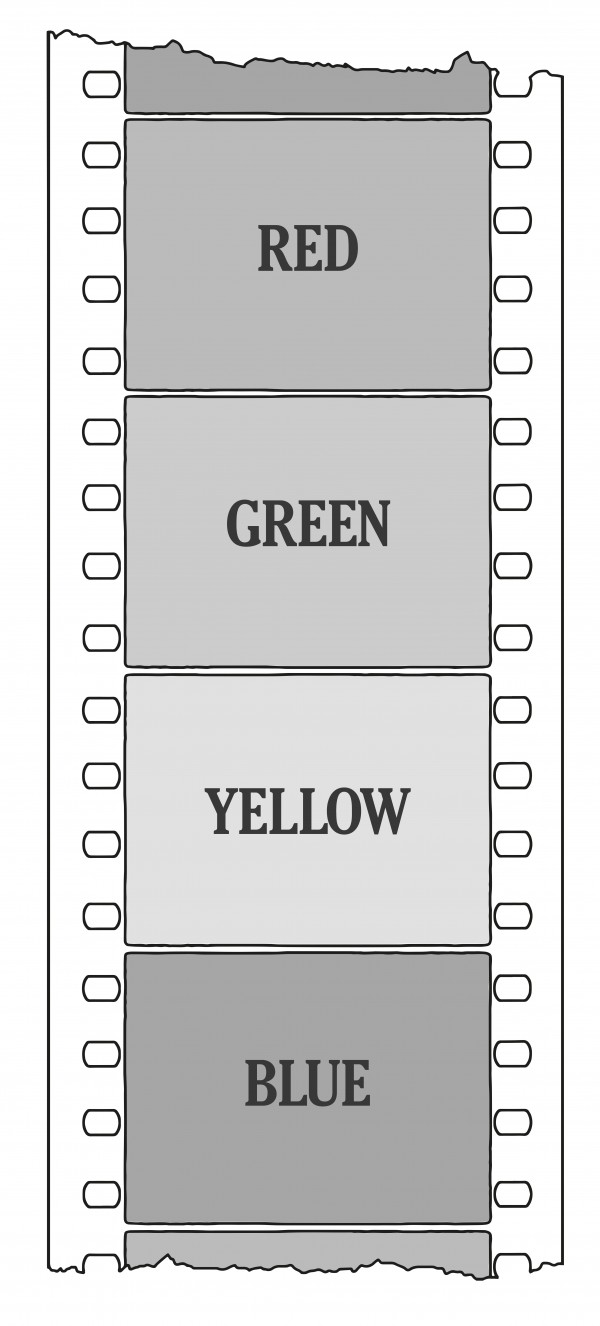

The Prizma four-colour negative captured red, green, yellow and blue frames consecutively onto B/W film through a rotating, colour filter wheel.

Design by Christian Zavanaiu.

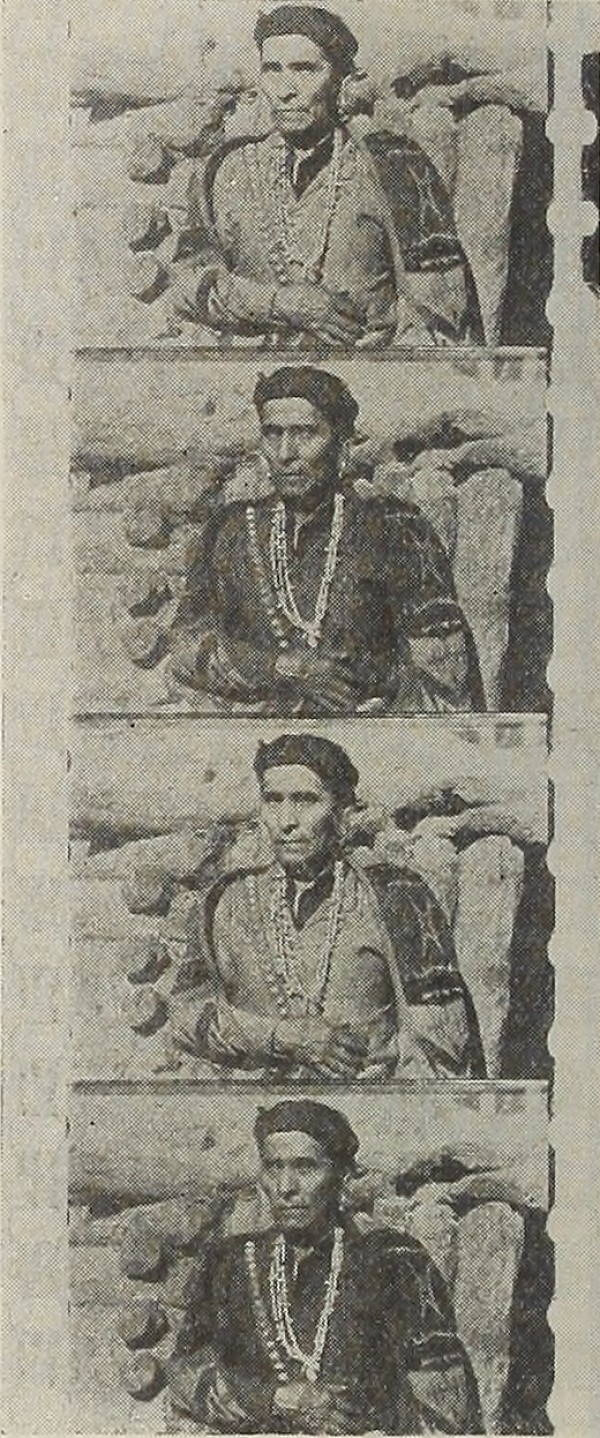

Although the Prizma four-colour print was B/W, the colour was revealed on screen during projection by projecting each colour record through a rotating filter wheel in front of the lens.

Identification

Unknown

B/W

Black mark on edge every 4 frames to identify the red-record frame.

1

B&W prints contained four color records (red, green, yellow and blue) in successive frames which appeared as different gradations on the print. The colors were revealed on screen in projection through a color filter wheel.

Unknown

Standard silent aperture.

negative pitch

B/W panchromatic.

Unknown

History

The Prizma four-colour additive process was the company’s first publicly demonstrated natural colour process and it was the precursor to later Prizma processes, as well as many other two-colour processes. During the less than two years of its existence, Prizma #1 colour films received positive reviews from both the film industry and the public. With the introduction of subtractive colour processes soon to arrive, Prizma’s four-colour additive process reportedly obtained some of the best results that an additive colour process could achieve. It was also one of the last processes to use colour projection filters to achieve natural colour on film.

The inventor William Van Doren Kelley had been experimenting with colour on film since 1912, when he developed a process called Panchromotion. He formed a company, with the same name, the following year in New York. After four years of research and experimentation – with Charles Raleigh, from Kinemacolor, and Elias B Koopman and Joseph Mason, from Biograph, on board – Panchromotion incorporated as Prizma in 1916, with capital amounting to $2 million (Theisen, 1936; Anon., 1916).

Prizma #1 was a four-colour additive process based on Kelley and Raleigh’s invention. It also built upon ideas patented by Max Mayer and Maurice J. Wohl. The Prizma camera took four-colour records in successive frames on a single negative through a colour filter wheel; the B/W positive film, with latent colour information, was then projected at 32 fps, through a spinning colour filter disc attached to a normal projector.

Like the early cinema pioneers, such as the Lumière brothers, Kelley sent his cinematographers with the Prizma cameras throughout the United States and the East Asia (China and Japan), in 1916, to make travelogue and nature films – the negatives were returned, and processed at the Prizma laboratory in Jersey City, New Jersey.

The first Prizma #1 colour film exhibition was on Thursday, February 8, 1917, at the auditorium of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Preceding each short subject screening, explanatory remarks were given by Ernest Fox Nichols, Professor of Physics at Yale University, regarding the application of scientific principles and laws of light and optics to the Prizma four-colour process (MacDonald, 1917). Later, these Prizma #1 colour films made their theatrical debut on February 25, 1917, at the Strand Theatre, Broadway, New York (Anon., 1917). After this debut, demand for four-colour Prizma shorts grew gradually among the cinemas and theatres of New York. All of these shorts were travelogues, or nature films, with subjects such as Niagara Falls, the Grand Canyon, the Pacific Coast, New Mexico and the like (MacDonald, 1917).

The first feature-length film photographed using the Prizma #1 colour system was Our Navy (1917), a 12-reel documentary film about the US Navy, filmed and directed by Dr. George A. Dorsey, a celebrated traveller and anthropologist. It was filmed during September 1917, and opened on Sunday evening, December 23, 1917, at the 44th Street Theatre, New York City – running for eight weeks (Anon., 1918a). After this successful run, the director Dr. Dorsey took the film on a tour of cities throughout the United States (Anon., 1918b).

As a diligent inventor, Kelley never stopped working to perfect the Prizma process. By the end of 1917, he had already successfully developed the next version of Prizma: a two-colour additive process employing an alternate-dye method. In this new process, alternate frames in the positive prints were dyed red and green. The result was like transferring the colour projection filters onto the film print itself, thus eliminating the need for the spinning filter wheel that previously had to be attached to the projector. The projector still had to run at 32 fps to achieve the natural colour effect on screen.

Although Our Navy was shot on four-colour negative, the opening screening of the film on December 23, 1917, was a demonstration of the new alternate-dye version of the Prizma process (Cory, 1918). However, since this process was complicated and time-consuming, not many prints of Our Navy were made using the alternate-dye method. As reported by The Washington Post, the screening of the film at the National Theater in Washington, DC, in July 1918, was still projected from a B/W print through a colour wheel filter (Anon., 1918c).

Kelley’s vision for natural colour films was to make them as easy to project as B/W prints, without the requirement for any attachments to the projector, or frame-rate adjustments. He eventually achieved this goal at the end of 1918 with the third version of Prizma process using double-coated positive film. The introduction of this improved version of the Prizma process marked the end of the Prizma’s four-colour additive process.

Selected Filmography

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

12-reel feature film. Screened at the following theatres, among others: 44th Street Theater, New York City; Tremont Temple, Boston; National, Washington, DC; Playhouse, Chicago.

12-reel feature film. Screened at the following theatres, among others: 44th Street Theater, New York City; Tremont Temple, Boston; National, Washington, DC; Playhouse, Chicago.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Short.

Technology

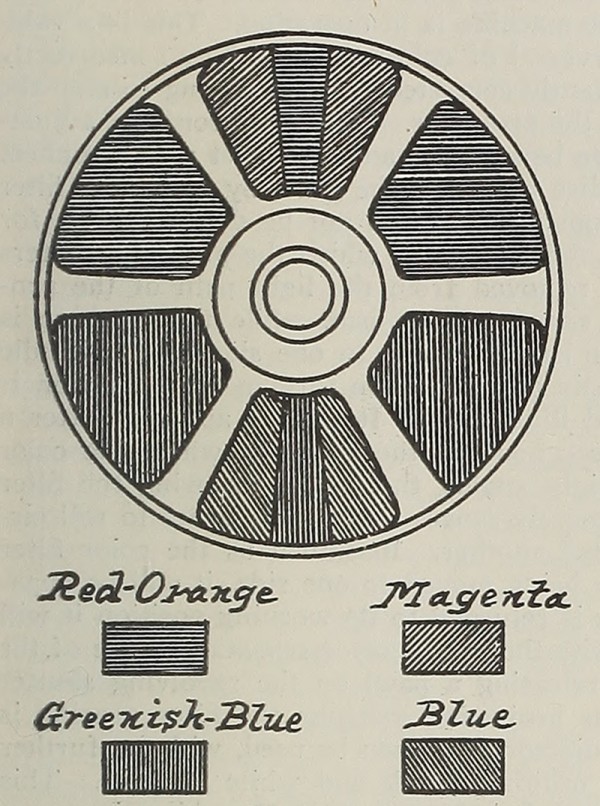

Prizma’s first additive process captured four-colour records – the same as Panchromotion. The negative colour values were recorded upon the film strip in sets of four images, with each one taken through a different colour filter. The colour filters were red-orange, blue-green, yellow and blue respectively, and their transmissions overlapped one another to a considerable extent. The decision to use four colours was to eliminate the dramatic pulsing effect, evident in vivid colours such as red and green, that plagued other two-colour additive processes. Because the four colour filters overlapped in their transmission curves, colours were less saturated.

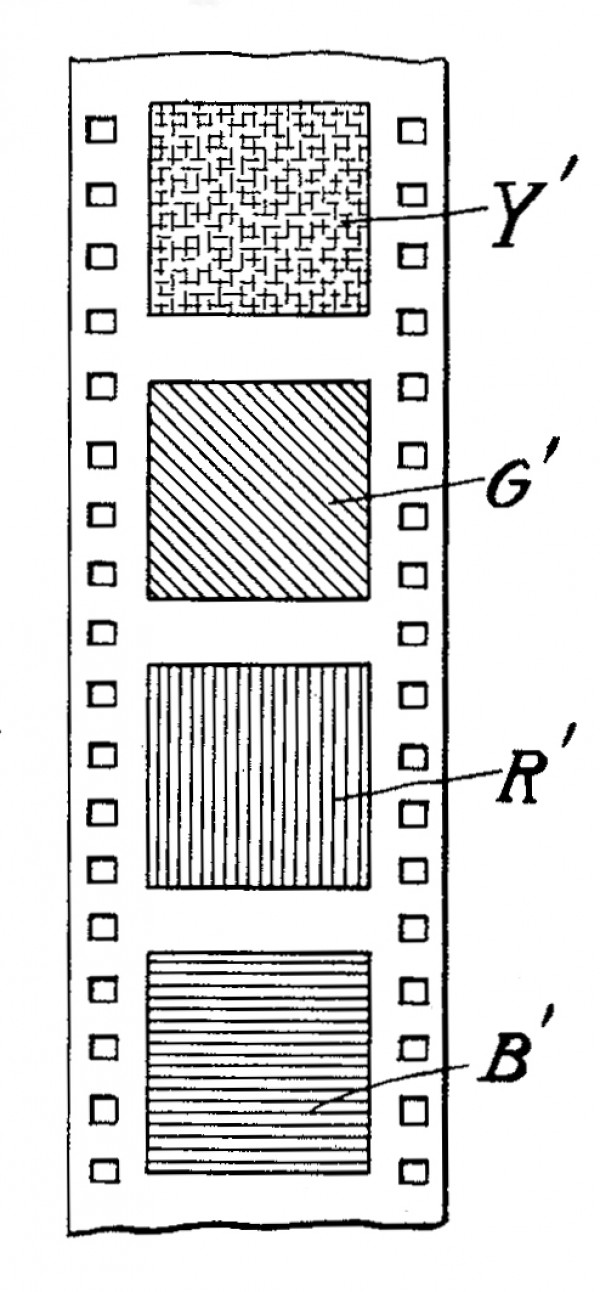

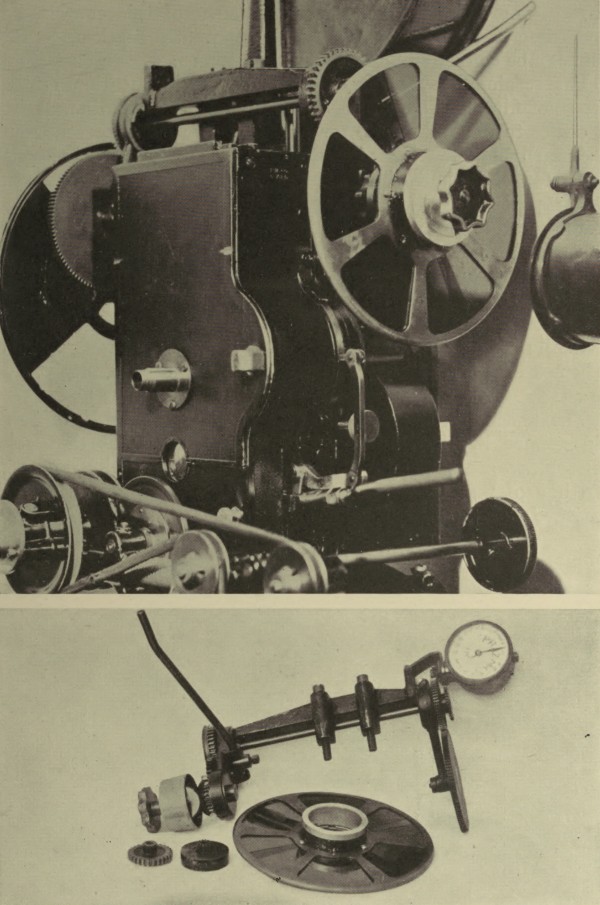

The Prizma camera employed a Geneva drive (‘Maltese cross mechanism’) and an intermittent sprocket. Each 360-degree crank revolution exposed 16 images and the negative records were produced at the rate of 26 to 32 images per second. The spectral transmissions of the four recording filters were red, transmitting light of wavelength (λ) from 715nm to 590nm; the yellow filter, light from 650nm to 550nm; the green, from 570nm to 470nm; and the blue, 550nm to 450nm (Cory, 1917). These two complementary pairs of colour (red/green; yellow/blue) used in making of the negatives, formed the fundamental principle of the subsequent Prizma Color processes.

Prints ran at twice the rate of standard B/W positives – 32 fps, through a special two-colour projection filter. Both the red and the yellow frames projected through a red-orange filter; while the green and the blue frames projected through a greenish-blue filter – instead of each colour frame projecting through a corresponding colour filter at four times the normal projection film speed (Cory, 1917). This was the intrinsic difference between Prizma’s four-colour process and the earlier Panchromotion. Panchromotion used a four-colour projection filter and never practically succeeded.

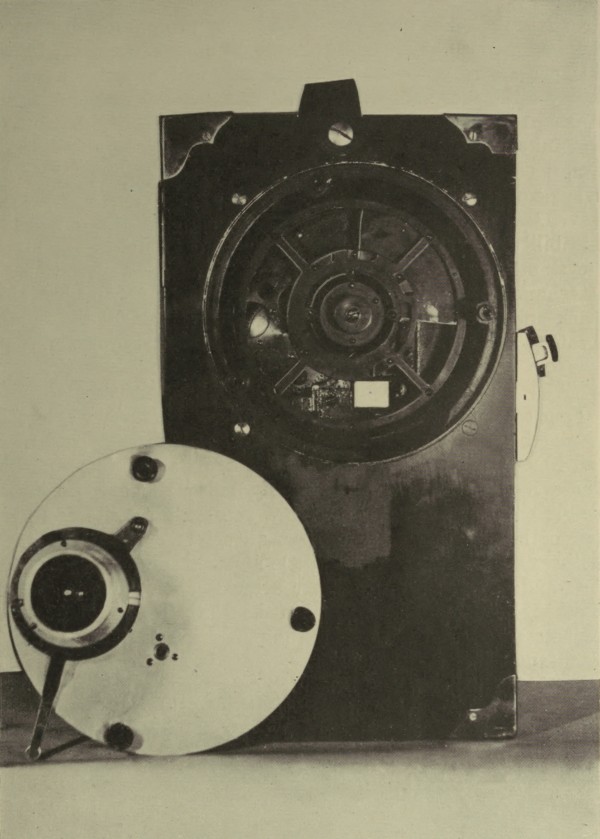

The Prizma projecting filter wheel, which made one complete revolution for every two images projected, consisted of six sections in two broad colour divisions. The filters were composed of suitably dyed gelatine films cemented in glass.

The filter attachment was designed to be easy to use. The filter wheel was mounted on an attachment in front of the lens which could be fixed to any standard Powers or Simplex projector of the time, without modification. The disc could be easily lifted out of the projection path, and returned, while maintaining the film and filter in perfect synchronisation (Cory, 1917; Crespinel, 1929).

Unidentified production. Four frames of Prizma positive film. Note that each frame in this B/W print contains a different colour record. The colour was revealed on-screen, during projection.Cory, Alfred S. (1917). “The Prizma Process of Color Cinematography”. Motion Picture News, 15:12 (March 24): p. 1890.

Cory, Alfred S. (1917). “The Prizma Process of Color Cinematography”. Motion Picture News, 15:12 (March 24): p. 1890.

Prizma four-colour negative with four colour records.

Raleigh, Charles & W. V. D. Kelley, Film or the Like for Color Photography. US patent US1216493A, filed April 13, 1916, and patented Feb. 20, 1917.

Prizma four-colour camera.

Lescarboura, Austin C. (1921). Behind the Motion-Picture Screen, p. 271. New York: Scientific American.

Prizma two-colour projecting filter wheel, with two small auxiliary filter elements. The red-orange and greenish-blue filters were primarily used in projection.

Cory, Alfred S. (1917). “The Prizma Process of Color Cinematography”. Motion Picture News, 15:12 (March 24): p. 1891.

Prizma projecting filter wheel attachment, mounted and unmounted.

Lescarboura, Austin C. (1921). Behind the Motion-Picture Screen, , p. 275. New York: Scientific American.

References

Anon. (1916). “Incorporations”. Motion Picture News (Jan. 29): p. 571.

Anon. (1917). “New Color Movies Shown”. New York Times (February 26): p. 10.

Anon. (1918a). “PRIZMA to Show “Our Navy” at 44th Street Theater”. The Moving Picture World, 35:1 (January 5): p. 56.

Anon. (1918b). “Prizma Film, Doresy-Directed, Tours”. Motion Picture News (Feb. 2): p. 711.

Anon. (1918c). “A Novel Color Scheme”. The Washington Post (July 14): p. R7.

Cory, Alfred S. (1917). “The Prizma Process of Color Cinematography”. Motion Picture News, 15:12 (March 24): pp. 1890–1892.

Cory, Alfred S. (1918). “Prizma’s Latest Color Pictures-An Advance Over Former Demonstration”. Motion Picture News (Jan. 12): p. 310.

Crespinel, W. T. (1929). “Color Photography: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”. American Cinematographer, 9:3 (March): pp. 5–7.

MacDonald, Margaret I. (1917). “Prizma Color Demonstration”. The Moving Picture World, 31:8 (February 24): p. 1201.

MacDonald, Margaret I. (1918). “Motion Picture Educator”. The Moving Picture World, 35:5 (February 2): pp. 659–663.

Theisen, Earl. (1936). “Notes on the History of Color in Motion Pictures”. International Photographer, 8:5 (June): pp. 8–9.

Patents

Kelley, William Van Doren & Charles Raleigh. Color Kinematography. GB patent GB191422921A, filed Nov. 23, 1914, and patented Feb. 23, 1916.

Raleigh, Charles & W. V. D Kelley. Film or the Like for Color Photography. US patent US1216493A, filed April 13, 1916, and patented Feb. 20, 1917. https://patents.google.com/patent/US1216493A

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Bin Li is a film restorer and analogue colour grader, working at Haghefilm laboratory in the Netherlands since 2014. He specialises in restoring unusual and highly damaged film materials, as well as recreating historical film colours. He was responsible for the restoration and digitisation of two big 68mm Biograph projects from the British Film Institute and the Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. He restored and digitised some of the very unique and damaged Étienne-Jules Marey materials, ranging from 26mm to 90mm, for La Cinémathèque française, Paris. Besides film restoration, Bin Li has also identified hundreds of lost films, including Love, Life and Laughter (1923), one of the BFI’s most wanted “lost films”.

The author would like to thank James Layton and Crystal Kui for providing extra research materials and appropriate illustrations for this entry.

Li, Bin (2024). “Prizma Color (four-color additive)”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.