An additive two-color alternate-dyed positive process developed by William Van Doren Kelley.

Film Explorer

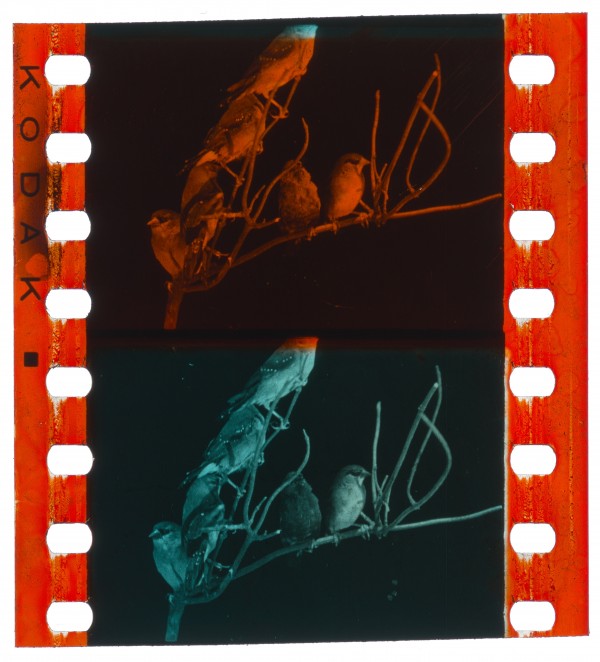

Unidentified film (c. 1917). A two-color additive Prizma color print with alternating red- and green-dyed frames. The Kodak edge code is from 1917.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

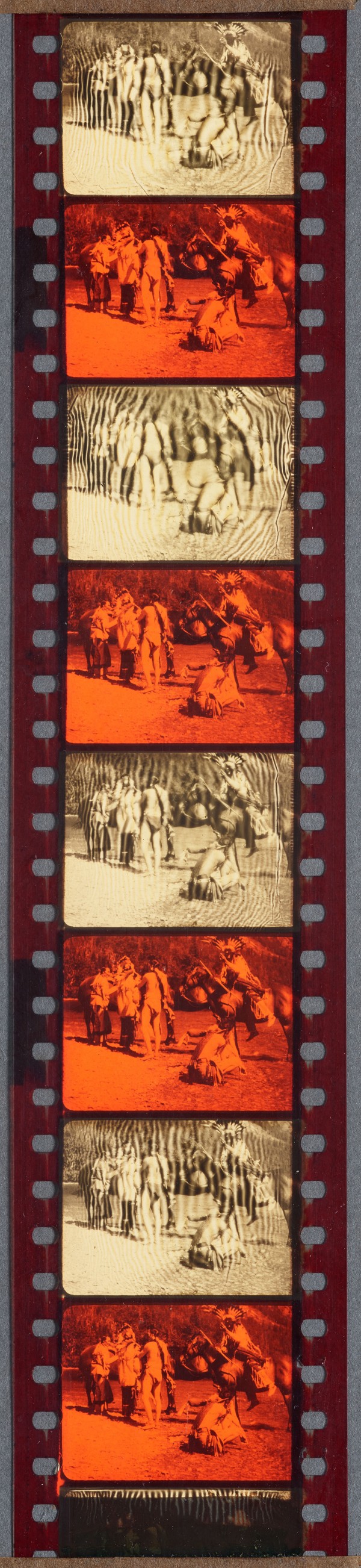

Unidentified film (c. 1916). A two-color additive Prizma color print. This rare film sample is mounted in a frame and it is likely that it was exposed to light for an extended period of time. As a result, the frames originally dyed green have faded.

National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States.

Identification

Standard silent aperture.

B/W. Alternate frames are dyed red and green.

Edges were dyed red.

1

Orange-red and green-blue dyed frames alternate, one after another. When projected at 32 fps it created a flickering natural color image on screen with a limited gamut, due to the fact it only had two complementary colors.

Unknown

Standard silent aperture.

B/W, panchromatic.

Black mark on edge every four frames, same as the first Prizma process.

History

Prizma Color’s two-color additive process was a short-lived, stop-gap process that arrived in late-1917. It was a bridge between the Prizma’s four-colour additive process and the later subtractive Prizma process. It used the same negatives as Prizma’s four-colour additive process, but changed the projection method from using color projection filters to alternate dyes on the film print. As a transitory process, the imperfection of Prizma’s two-color additive process was clear in both the technology and the results on-screen. However, by eliminating the color projection filter, Prizma’s two-color additive process brought the inventor William Van Doren Kelley’s vision for natural color films one step closer, by adding the color to the film print so it could be projected using the same equipment as used for standard B/W films, only at a higher speed of 32 fps.

After the theatrical debut of Prizma’s four-colour additive process on February 25, 1917, at the Strand Theatre in New York City, the drawbacks of the four-color additive process became noticeable. The high projection rate of 32 fps caused the perforations to break with an alarming frequency, which interfered with the required perfect synchronization of the film and the color projection filters. This damage, caused by high projection speeds, also reduced the life of the film print to about one-third of its normal life (Moving Picture World, 1919; Kelley, 1919). Soon after, Kelley’s collaborator and one of the founders of the Prizma Inc., Charles Raleigh, left the company, as he doubted the additive method would ultimately prove successful in achieving natural color on film (Crespinel, 1929).

As an inventor, and a technically minded person, Kelley remained committed to the additive method and quickly made progress in eliminating many of the drawbacks of Prizma’s four-color additive process. The first key step towards that goal was the development of the method known as the alternate-dye method. It was a means of obtaining color results without the need for the color projection filter attachment required by the earlier process. The positive prints were alternately dyed red and green, frame after frame – effectively applying the color projection filters directly onto the film print itself. The projector, however, still needed to run at 32 fps to obtain the illusion of color on screen as a result of the persistence of vision. Although Kelley regarded this system as far from perfect, it was a step in the right direction in comparison to Prizma’s existing four-color additive process.

The first public performance of the new process came with the premiere of the feature film Our Navy (1917), plus several short subjects, on December 23, 1917, at the 44th Street Theatre, New York City. According to contemporary reports, the whites of the subjects were sparkling clear, an indication that the color dyes used were complementary to one another – at least, very nearly so. Pure greens and yellows, however, were still unobtainable, as noted by Motion Picture News (Cory, 1918). The screen result, remembered many years later by Leopold Godowsky, Jr. (co-inventor of Kodachrome), had poor definition, was artificial and very unsatisfactory – additionally it was a difficult and cumbersome process to operate (Godowsky, 1971).

Despite the imperfections of Prizma’s two-color additive process, Our Navy was screened around the country during 1918 and, from the second half of the year, also in edited versions of various lengths, renamed as Our Invincible Navy ( Motion Picture News, 1918a; Motion Picture News, 1918c). During this time of war, the film was praised for its educational content and patriotic nature, rather than its technical achievements. It was also shown at the White House, Washington, DC, on February 11, 1918 (Motion Picture News, 1918b).

It is hard to know precisely the number of film prints made using the alternate dye method, given the challenging nature of the dyeing process. Local screening reports of Our Navy indicate that some screenings still used color projection filters rather than alternate-dyed frame prints (Washington Post, 1918). One article advertising the film to theatre managers stated that, “if you could afford the slight re-arrangement of your projection machinery, necessary for the showing of Prizma natural color pictures, … ‘Our Invincible Navy’ is a splendid four-reel subject as an added feature attraction.” (Motion Picture News, 1918c).

Another explanation for the limited use of the Prizma’s two-color additive process might be the temporary departure of Kelley from Prizma Inc. during 1918, who left to pursue experiments with the subtractive Kesdacolor process. By the end of 1918, Kelley had returned to Prizma Inc. with yet another improved version of the Prizma process launched in early 1919, now employing double-coated positive film, which finally made Prizma Color films compatible with standard B/W projection equipment, at a standard projection speed.

Selected Filmography

Remarkable views of the Hawaiian volcano Kilauea. This film exists in various versions using different Prizma processes.

Remarkable views of the Hawaiian volcano Kilauea. This film exists in various versions using different Prizma processes.

An authentic and thorough portrayal of the US Navy. Showcases the history, education, training, drilling and everyday activities on various navy vessels, as well as the building of various battleships.

An authentic and thorough portrayal of the US Navy. Showcases the history, education, training, drilling and everyday activities on various navy vessels, as well as the building of various battleships.

Technology

The principle of Prizma’s two-color additive process was similar to earlier British color process known as Biocolour and films made by the Aurora Film Company. B/W prints containing alternate red and green color records were dyed those respective colors, one frame after another. The color filters were effectively applied to the film print itself rather relying on a rotating projection filter wheel.

The negative was taken using the existing Prizma camera at 32 fps using a panchromatic B/W stock. It contained double complementary pairs of images (four frames). One pair recorded red-orange and blue-green values; while the second pair recorded orange and blue values. A B/W print was then contact printed from this negative. Subsequently, the red-orange and orange frames were dyed red, and the blue-green and blue frames were dyed green. When projected at 32 fps, the complementary images blended (as a result of the persistence of vision) to create the perception of a crude natural color image for the viewer.

The difficulty of the process was in applying the colors to their respective areas uniformly, because the print had to be colored alternately red and green throughout its length. The first experiment was achieved by applying lacquer coverings to protect all of the red frames on a 50-ft (15.24m) length print. This meant applying dye-resistant lacquer to 400 frames by hand, which was extremely crude and time-consuming. The film was then immersed into the green dye bath, washed and dried. The lacquer coverings, which had protected the red images from the green dye, were then removed, and the green images were lacquered in the same manner. Then the entire film was immersed into a red dye bath, washed and dried, completing the operation. This method was quickly abandoned for obvious reasons.

A simpler, more efficient method was perfected following various iterations. In this improved method, the full print was immersed in the green dye, then washed and dried. The print was subsequently run through a machine which sprayed a thin coating of waterproof lacquer onto the green picture record frames only, after which the films were immersed in running water which quickly removed the green dye from the unprotected frames. The film was then placed in the red dye bath, and the dye was absorbed only on the unprotected red picture frames (Crespinel, 1929), hence the red edge color on the existing samples.

Since this method only involved the positive prints, it could be applied to any films made using Prizma’s four-color additive process. Indeed, the method was even applicable to Kinemacolor prints, or other color systems of that nature.

Despite representing a technical step forward for Prizma Color, the complex and time-consuming nature of this alternate-dyed frame process, along with the unsatisfactory results on-screen, made this the shortest-lived Prizma Color process.

References

Cory, Alfred S. (1917). “The Prizma Process of Color Cinematography”. Motion Picture News (March 24): pp. 1890–92.

Cory, Alfred S. (1918). “Prizma’s Latest Color Pictures-An Advance Over Former Demonstration”. Motion Picture News (Jan. 12): p. 310.

Crespinel, W. T. (1929). “Color Photography: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”. American Cinematographer, 9:2 (Mar.): pp. 5–7.

Godowsky, Leopold Jr. (1971). Oral History Memoir. New York, NY: American Jewish Committee, William E. Wiener Oral History Library.

Kelley, William V. D. (1918). “Natural Color Cinematography”. Transactions of the SMPE, 7 (November): pp. 38–43.

Kelley, William V. D. (1919). “Adding Color to Motion”. Transactions of the SMPE, 8 (April): pp. 76–9.

MacDonald, Margaret I. (1917). “Prizma Color Demonstration”. Moving Picture World, 31:8 (February 24): p. 1201.

Motion Picture News (1918a). “Prizma Film, Doresy-Directed, Tours”. Motion Picture News (Feb. 2): p. 711.

Motion Picture News (1918b). “Our Navy Shown at White House”. Motion Picture News (Mar. 2): p. 1265.

Motion Picture News (1918c). “Our Invincible Navy”. Motion Picture News (Jul. 6): p. 108.

Moving Picture World (1918). “PRIZMA to Show ‘Our Navy’ at 44th Street Theater”. The Moving Picture World, 35:1 (January 5): p. 56.

Moving Picture World (1919). “Prizma to Use Standard Projectors”. Moving Picture World, 39:2 (Jan. 11): p. 190.

Theisen, Earl. (1936). “Notes on the History of Color in Motion Pictures”. International Photographer, 8:5 (June): pp. 8–9.

Washington Post (1918). “A Novel Color Scheme”. The Washington Post (Jul. 14): p. R7.

Preceded by

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Bin Li is a film restorer and analogue colour grader, working at Haghefilm laboratory in the Netherlands since 2014. He specialises in restoring unusual and highly damaged film materials, as well as recreating historical film colours. He was responsible for the restoration and digitisation of two big 68mm Biograph projects from the British Film Institute and the Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. He restored and digitised some of the very unique and damaged Étienne-Jules Marey materials, ranging from 26mm to 90mm, for La Cinémathèque française, Paris. Besides film restoration, Bin Li has also identified hundreds of lost films, including Love, Life and Laughter (1923), one of the BFI’s most wanted “lost films”.

The author would like to thank James Layton and Crystal Kui for providing extra research materials and appropriate illustrations for this entry.

Li, Bin (2025). “Prizma Color (two-color additive)”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.