A subtractive, three-color, dye-bleach multilayer print film with a dynamic range of brilliant colors, widely used in European animation and avant-garde film production in the 1930s.

Film Explorer

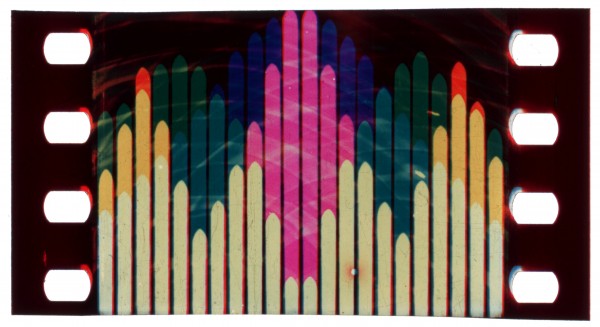

[Gasparcolor tests by Oskar Fischinger] (c. 1933). These tests are silent: however, most Gasparcolor prints include an optical soundtrack.

Earl Theisen Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

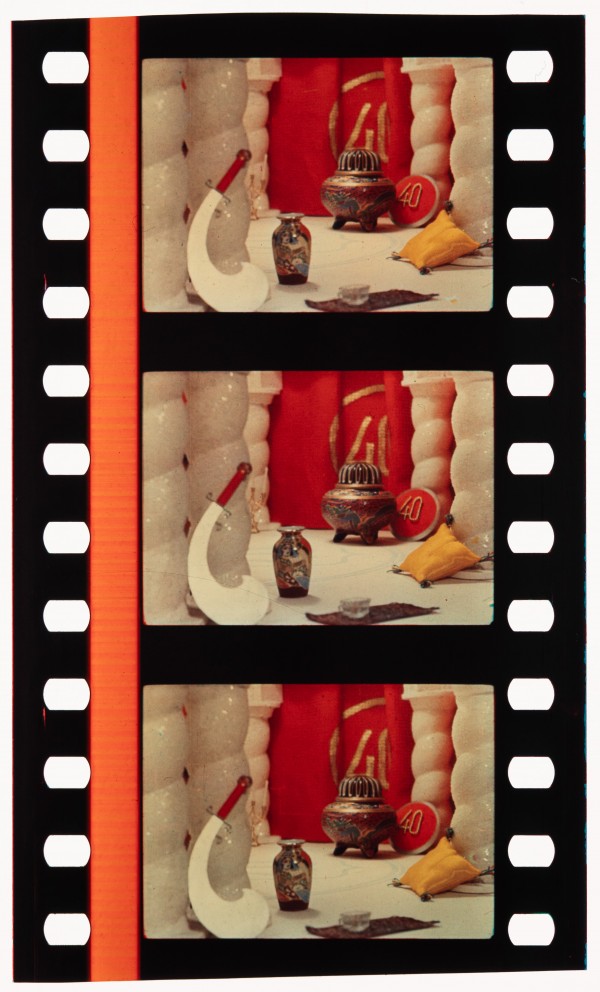

George Pal’s puppet animation Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs (1935). Gasparcolor prints often feature vibrant soundtracks, colored in orange, magenta, or green.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Unidentified French commercial, possibly by Alexandre Alexeieff (1930s).

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

A 35mm Gasparcolor print of the German short Norddeutscher Lloyd Bremen (c. 1936). This print features a magenta variable-density soundtrack.

Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, Germany. Scan by Sebastian Herhaus and Paul Marie.

The original successive exposure camera negative of Len Lye’s The Birth of the Robot (1936). Red, green and blue color records were captured, one after the other, on panchromatic B/W film.

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom. Photograph by J. M. Fernandes.

Identification

A 16mm variant was available in the early 1940s in the United States, according to some sources.

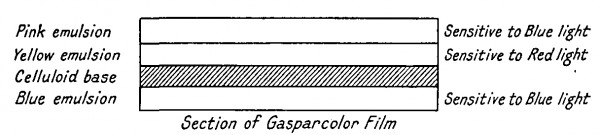

Three-color chromolytic multilayer. Gasparcolor print film was composed of three superposed emulsions: a cyan layer on one side of the film and two layers (magenta and yellow) on the other side. The color image was produced by a chemical process that destroyed the excess dye particles in each layer corresponding to the amount of silver that was developed in the image.

No specific Gasparcolor markings, the edges of the film strip are always black. The following film manufacturer markings are sometimes visible: KODAK A.G., EASTMAN KODAK, SELO.

1

Gasparcolor is best known for its three-color variant, which was frequently used in animation and was able to reproduce a wide array of vibrant and dynamic colors. The process was especially suitable for animation films; very few live-action Gasparcolor films were ever produced.

Procédé Gasparcolor, In Gaspar Color, Gaspar-Color, Gasparcolor, Gaspar-Color Farben-Fotografie, Printed in Gasparcolor. Also frequently found is a closing logo with a parrot and, usually, a Geyer-Kopie stamp.

The Gasparcolor positive was compatible with all contemporary types of optical sound recording, such as variable-area and variable-density soundtracks. The soundtrack area is colored, sometimes presenting two colors, depending on the colors of the multilayer film strip. Documented colors of the soundtrack area include magenta, red, purple, orange, blue, and green – all in different shades, depending on the specific print.

Panchromatic B/W negative, capturing red, green and blue color records, either produced successively, or simultaneously with a beam-splitter camera. Print-through edge print from surviving prints indicates Kodak, Kodak-Pathé and Kodak A.G. negative was used.

Standard US, French or German Eastman Kodak edge markings; Ilford (Selo) edge markings on some British films.

History

Introduced in Germany, in 1932, by Hungarian-born Béla Gáspár (1898–1973) and his brother Imre, Gasparcolor quickly captured the attention of avant-garde filmmakers such as Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye and Alexander Alexeïeff, with its vibrant hues, becoming a popular choice for animation films in the 1930s.

Gasparcolor's technological roots can be traced back to experiments exploring the silver dye bleach process for still photography, first theorized in the writings of R. E. Liesegang in 1889 and elaborated upon by Karl Schinzel, for his process Katachromie, and by Danish inventor Jens Herman Christensen. However, it was Béla Gáspár and his brother Imre who founded the company Gasparcolor Naturwahre Farbenfilme GmbH in Berlin in 1930 and patented Gasparcolor in Germany in 1932, making it the first viable silver dye bleach process for color cinematography. In order to achieve this, Gasparcolor initiated an important collaboration with Geyer-Werke AG, a well-known film factory and film services provider in Berlin.

At the time of Gasparcolor’s introduction in Germany at the beginning of the 1930s, several companies and inventors were keen to develop a new and reliable color film technology to compete with the American Technicolor and to demonstrate German technological prowess. This resulted in a series of color film processes being developed in Germany in the 1930s, amongst which were Berthon-Siemens, Agfacolor Neu and Pantachrom.

The 1920s and 1930s also witnessed an increased intensity in experimental and avant-garde filmmaking, with artists exploring the fusion of color, motion and music to create a "Gesamtkunstwerk" – that is, a total work of art comprising different art forms – following the artistic and sometimes spiritual concept of “synesthesia” (the simultaneous perception of multiple sensory stimuli in one gestalt experience). In this artistic context, Gasparcolor became a fruitful tool for avant-garde filmmakers, including Oskar Fischinger whose films, such as Kreise (1933), exemplified the synergy of visual and auditory elements.

As a result, Gasparcolor found its place in advertising, a burgeoning industry that provided avant-garde filmmakers with a commercial platform for creative experimentation, and particularly for animation. A second Gasparcolor company, the Gasparcolor Werbefilme GmbH, was founded in order to focus on the production of advertising films. With growing implementation, the process’ success extended beyond Germany, reaching the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, and France, where artists such as George Pal and Alexander Alexeïeff embraced the process. Consequently, Gasparcolor was able to rapidly expand. In 1934 the subsidiary Gasparcolor Ltd. was founded in London, managed by Adrian Klein (later Adrian Cornwell-Clyne). After leaving Germany, Gáspár himself ran a laboratory in Luxemburg until 1940, when he emigrated to the United States.

However, live-action films presented challenges for Gasparcolor due to lengthy exposure times required for the successive capture of color separations, resulting in color fringing on moving subjects. Consequently, Gasparcolor was rarely used for live-action films, with Adrien Klein's documentary Colour on the Thames (1936) being the only known surviving live-action Gasparcolor film. Importantly, however, Klein shot this film with a beam-splitter camera, thus avoiding successive photography with its associated issues to a certain extent.

In Germany, experiments with a beam-splitter camera were also underway in the mid-1930s, with two live-action shorts produced in 1938 by Epoche-Gasparcolor – only the first, Erinnerungen vor dem Spiegel (1938), a commercial, was publicly presented, while the second, a short musical revue, was never screened. According to archival sources, the beam-splitter camera used for these two films had been produced by a Dr. Asche, who was working for the Paris-based arm of Paramount as a color film specialist.

At the same time, the political climate in Germany shifted dramatically after 1933, with the Nazi regime targeting both Jewish filmmakers and the artistic avant-garde as part of its propaganda efforts. Labelled “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art), modernist and avant-garde art was declared to be un-German, Jewish or Marxist. In 1936 all modernist art was banned and, in 1937, the exhibition Entartete Kunst in Munich presented 650 examples of confiscated art before the artworks were hidden, sold or destroyed. The escalating political situation prompted dozens of members of the film industry, including Béla Gáspár and Oskar Fischinger, to leave the country.

In 1935, the Gasparcolor company was merged with Werbefilm-Epoche, creating the company Epoche-Gasparcolor, and ‘Germanized’ – after which Béla Gáspár had no formal ties to the German Gasparcolor companies. Press reports of a Gasparcolor film demonstration later the same year emphasize that Gasparcolor was a German process, invented and implemented by Germans (Orosz, 2012: p. 349), temporarily erasing Gáspár from the process’ history.

Another significant hurdle for Gasparcolor was a protracted patent dispute with Agfa, a regime-linked company owned by I. G. Farben, the largest German chemical conglomerate and producer of film and photography supplies. The dispute lasted nearly a decade, with both companies objecting to the other's patents, as Agfa's experimentation with dye bleach processes, which at least partially informed Agfa’s process Pantachrom, paralleled Gáspár's work, leading to ongoing dispute that fundamentally hindered the further development of Gasparcolor. This was particularly delicate as Gasparcolor was dependent on Agfa’s Tripofilm raw stock for its film prints.

With the outbreak of the World War II, the introduction of Agfa's chromogenic process Agfacolor Neu in 1939, and the repression of avant-garde filmmaking in Germany, Gasparcolor began to fade. The ongoing patent dispute in Germany, and the competition's continued efforts to discredit Gasparcolor, culminated in the cessation of production in the early 1940s. Béla Gáspár moved to the United States, where he continued his research into color film and photography, but was unable to commercialize his inventions – ultimately, he resolved to sell his patents to Technicolor. Subsequently, both a two- and three-color version of Gasparcolor was briefly promoted in the United States, but this seems to have been a very short-lived venture, and very little documentation of this phase exists today (Wyckoff, 1941: p. 510).

However, from the 1960s onwards, based on Gáspár’s previous work, the Swiss company Ciba implemented a silver dye-bleach process for still photography under the names Cibachrome and Ilfochrome, in collaboration with Ilford. The process was developed by Gáspár's former collaborator Paul Dreyfus, who joined Ciba AG after Gáspár's death and used the expired Gasparcolor patents to develop Cibachrome (Fazekas, 2022: p. 125).

Selected Filmography

One of Oskar Fischinger’s last Gasparcolor films and possibly one of the last Gasparcolor films produced. Commenced during Fischinger’s time at Paramount, but completed later, with the support of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York (today the Guggenheim Museum).

One of Oskar Fischinger’s last Gasparcolor films and possibly one of the last Gasparcolor films produced. Commenced during Fischinger’s time at Paramount, but completed later, with the support of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York (today the Guggenheim Museum).

Short animated commercial for the German tyre company Tolirag. Also known as Kreise, this is Oskar Fischinger’s first film in Gasparcolor.

Short animated commercial for the German tyre company Tolirag. Also known as Kreise, this is Oskar Fischinger’s first film in Gasparcolor.

Short experimental animated promotional film by multidisciplinary artist and filmmaker Len Lye. The film was sponsored by Imperial Airways.

Short experimental animated promotional film by multidisciplinary artist and filmmaker Len Lye. The film was sponsored by Imperial Airways.

Short documentary film. The only known surviving live-action film in Gasparcolor, shot by Adrien Klein (also known as Adrian Cornwell-Clyne), a British color film expert and technical manager of the British Gasparcolor subsidiary in London.

Short documentary film. The only known surviving live-action film in Gasparcolor, shot by Adrien Klein (also known as Adrian Cornwell-Clyne), a British color film expert and technical manager of the British Gasparcolor subsidiary in London.

A short animated commercial for the Telefunken radio receiver, animated by the influential Czechoslovakian animation duo Irena Dodalová and Karel Dodal.

A short animated commercial for the Telefunken radio receiver, animated by the influential Czechoslovakian animation duo Irena Dodalová and Karel Dodal.

Short animation film by German filmmaker Hans Fischerkoesen, who was commissioned, after the start of the World War II, to produce German animation films comparable to Walt Disney’s output.

Short animation film by German filmmaker Hans Fischerkoesen, who was commissioned, after the start of the World War II, to produce German animation films comparable to Walt Disney’s output.

Short live-action commercial film for a facial cream, shot with a beam splitter camera. Kaskeline was one of the most prolific commercial film directors and producers in Germany and continued successfully throughout the Nazi regime, despite being half Jewish, as he received a special permit for artists which allowed him to continue working.

Short live-action commercial film for a facial cream, shot with a beam splitter camera. Kaskeline was one of the most prolific commercial film directors and producers in Germany and continued successfully throughout the Nazi regime, despite being half Jewish, as he received a special permit for artists which allowed him to continue working.

Puppet animation commercial for Tungsram electric light bulbs by Gyula Macskássy and György Szénásy, the former being one of the most prolific and influential Hungarian animation directors and graphic artists.

Puppet animation commercial for Tungsram electric light bulbs by Gyula Macskássy and György Szénásy, the former being one of the most prolific and influential Hungarian animation directors and graphic artists.

Animated short set to Modest Mussorgski’s composition of the same name. Animated by Russian–French animation filmmaker Alexandre Alexeïeff in collaboration with Claire Parker, with whom he developed innovative approaches to animation film. Alexeïeff would later be invited to work in Berlin for Gasparcolor from 1936–38.

Animated short set to Modest Mussorgski’s composition of the same name. Animated by Russian–French animation filmmaker Alexandre Alexeïeff in collaboration with Claire Parker, with whom he developed innovative approaches to animation film. Alexeïeff would later be invited to work in Berlin for Gasparcolor from 1936–38.

Short stop-motion commercial for Philips Radio by George Pal. Pal would later become an important figure for American science-fiction and fantasy film.

Short stop-motion commercial for Philips Radio by George Pal. Pal would later become an important figure for American science-fiction and fantasy film.

Technology

The three-color reversal Gasparcolor print film was based on the principles of the silver dye-bleach process and had a multi-layer structure with three different color-sensitive silver halide emulsions: a cyan layer on one side, and magenta and yellow layers on the other side.

The production of the three-color print film required B/W separation records for red, green and blue. Importantly, Gasparcolor’s innovation concerned the print material only, not the production of the color separations. At the time, separation negatives on panchromatic material could be obtained by successive exposure through the corresponding filters (temporal synthesis), or by simultaneous exposure through multiple lenses or a beam splitter (spatial synthesis). While Technicolor introduced a three-color beam-splitter camera in 1932, these weren’t universally available, and most companies resorted to successive exposure, which was easily accessible. One major issue of successive photography is an effect called temporal parallax, that is, the (even minute) displacement of objects in front of the camera between one color record and the next, causing discrepancies between the color separations, resulting in visible color fringing on the final print film. This effect was particularly pronounced for processes like Gasparcolor, which required long exposure times. In the case of animated film, this obviously didn’t matter, as they allowed for almost total control of pre-filmic movement, in contrast to live-action film. This was the primary reason for why Gasparcolor was only rarely implemented for live-action films, and why, as discussed above, it was attempted only using beam-splitter cameras.

In contrast to chromogenic film materials such as Kodachrome, Eastman Color or Agfacolor, which contained color couplers in the film emulsion, with Gasparcolor the dyes themselves were contained within the photographic emulsion layers and a silver dye-bleach process was used to destroy the dyes in a controlled way, relative to the amount of developed silver remaining in the emulsion. While it would have been theoretically possible to work with dye couplers, Gáspár preferred to incorporate ready-made dyes directly into the emulsion, so that the concentration of the dyes and the resultant outcome could be better determined in advance (Gáspár, 1935: pp. 121–2). Importantly, Gáspár also introduced a new method for sensitizing the multilayer material. In fact, he states that one should avoid striving for a sensitivity that is complementary to the coloring of the layers in order to achieve successful color images in the different layers (Gáspár, 1935: p. 123).

From the three B/W separation records, three intermediate positives were produced and printed onto the corresponding layers of the Gasparcolor print film. For most of the German film prints, Agfa Tripofilm was used up until the late 1930s, while an alternative film stock was produced by Belgian company Gevaert. Through a chemical reaction, the images were transformed into dye images and fixed, after which the dyes in the three layers were destroyed proportionally to the developed silver image. After an intermediate rinse, the excess silver was removed. All baths and developing steps were simultaneous in all three color layers. The resulting Gasparcolor print presents three dye images, one on top of the other.

Due to its technological specificities, a Gasparcolor film print is easily recognizable. Most strikingly, the process is characterized by pure, brilliant and intense colors, while the perforation area is black (indicating that it is a reversal process – the multilayer print was exposed as a duplicate negative and converted into a positive), and the sound track colored in different colors, from magenta to red, purple, orange, blue and green. Moreover, Gasparcolor prints often display small pools of color as well as signs of use (such as scratches, tears, and splices), which reveal the different color layers in the print. Amongst the advantages of the process, in addition to the beautiful colors, are its high stability, its resistance to color fading, and the creative potential it provides. Nonetheless, the process presented various technological challenges, first and foremost in the production of live-action images.

Based on archival materials and a few articles and advertisements, it appears that a second Gasparcolor process existed in the early 1940s: a two-color process marketed by the Vitacolor lab in Burbank, California. Unfortunately, very little is known about this variant and only fragments of test films seem to have survived.

The Gasparcolor print contained magenta (pink) and yellow emulsion layers on one side, with a cyan (blue) layer on the other side of the base.

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography. London: Chapman & Hall.

A rare example of the Gasparcolor two-color process, date unknown.

Earl Theisen Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

References

Fazekas, Molnár (2022). “Challenges of Gasparcolor Technology in the Digital Restoration of Gyula Macskássy Commercials”. Journal of Film Preservation, 107: pp. 121–9.

Gáspár, Béla (1935). “Neuere Verfahren zur Herstellung von subtraktiven Mehrfarbenbildern (Gasparcolor-Verfahren)”. Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Photographie, Photophysik Photochemie, 34: pp. 119–24.

Heymer, Gerd (1935). “Farbenfilme nach dem Silberbleichverfahren”. Veröffentlichungen des wissenschaftlichen Zentral-Laboratoriums der photographischen Abteilung Agfa, 4: pp. 177–86.

Ignatow, G. (1937). “Das Gasparcolor-Verfahren zur Herstellung von Dreifarbenfilmen”. Kinotechnik, 19:6 (May): pp. 126–7.

Jakobsohn, K. (1933). “Gasparcolor, eine Lösung des Problems der Farbenphoto- und Kinematographie”. Kinotechnik, 15:15 (August): pp. 248–9.

Klein, Adrian B. (1936). “The Gasparcolor Process”. International Photographer, 8:5 (June): pp. 6–7.

Orosz, Márton (2012). “The Hidden Network of the Avant-Garde: der farbige Werbefilm als eine zentraleuropäische Erfindung?”. In Regarding the Popular: Modernism, The Avant-Garde and High and Low Culture, Sascha Bru et al. (eds), pp. 338–61. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Schellenberg, Matthias, Ernst Riolo & Hartmut Blaue (2007). “Silver-Dye Bleach Photography. Basic Color Photographic Principles, History of Silver-Dye Bleach”. In The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography, Michael R. Peres (ed.), pp. 700–11. Amsterdam and New York: Elsevier and Focal Press.

Wyckoff, A. (1941). “Gasparcolor Comes to Hollywood”. American Cinematographer, 22:11 (November): pp. 510–11.

Patents

Compare

Related entries

Author

Noemi Daugaard is a film scholar based in Zurich with a special interest in color film technology. She works for the Swiss National Science Foundation as well as several Swiss film festivals.

Thank you to Barbara Flueckiger and the Timeline of Historical Film Colors for fundamental insights and to James Layton for very relevant information concerning the two-color version of Gasparcolor.

Daugaard, Noemi (2024). “Gasparcolor”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.