A Belgian subtractive two-color process that used chemical and dye toning to create a color image on a single emulsion layer. In 1936, the process was upgraded to three-color.

Film Explorer

Jolis contes de fées (1935) by Paul Marinier. Dascolor was a two-color process used in Belgium.

Cinémathèque royale de Belgique – Cinematek, Brussels, Belgium.

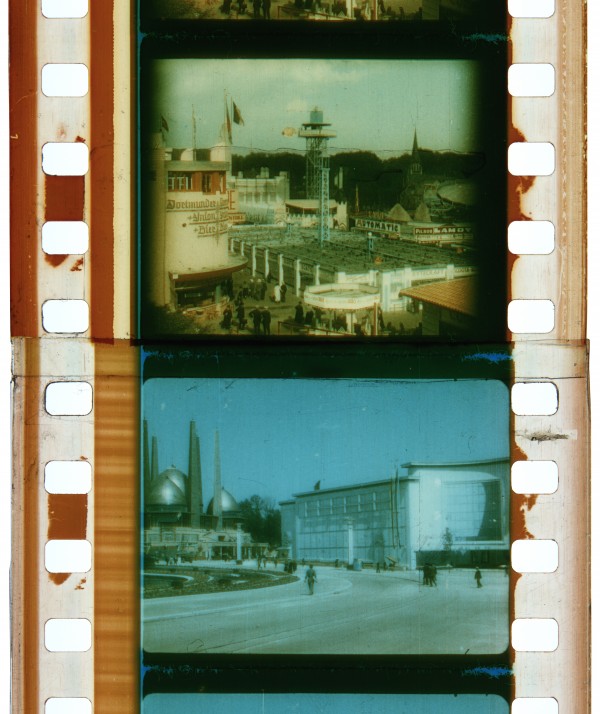

A 35mm Dascolor print of Ce que nos yeux ne verront plus (1935). Dascolor prints have a characteristic coppery orange soundtrack.

A 35mm print of Small Fish Fry by Adrian Vanderhorst (c. 1935/6). Dascolor’s two-color palette could not reproduce all colors of the spectrum, but if colors were carefully selected, the results proved pleasing.

Identification

Approximately 21.0mm x 15.2mm (0.825 in x 0.600 in).

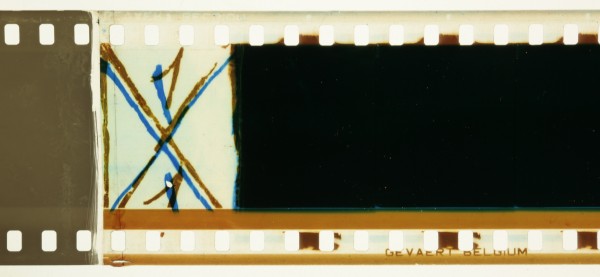

Gevaert positive film stock. A single emulsion, twice sensitized and exposed, to contain two color records, toned orange and blue.

GEVAERT BELGIUM in orange-colored letters. Dascolor prints at the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique all feature an orange box that appears to the left of the soundtrack between the perforations – repeated every frame – possibly a remnant from the film printer used.

1

A two-color system composed of the colors orange and blue. The overall color spectrum is greenish, flesh tones are only fairly accurate, variations in blue are rendered better than neutrals, or reds. Sharpness is finely chiseled; the soft contrast nicely preserves details in dark areas. The first frames of a new shot sometimes suffer from inaccurate registration, resulting in some color fringing.

Dascolor

Surviving samples include variable-area and variable-density soundtracks, printed in a coppery orange.

Unknown

Gevaert B/W bipack negatives.

GEVAERT BELGIUM

History

The Dascolor process was invented by Léon-Josse Dassonville (1887–1975), pioneer of the cinematographic industry in Belgium. Research has uncovered information on seven short subjects shot in Dascolor, of which four survive – all made between 1934 and 1936 – suggesting that the exploitation of the Dascolor process was limited to a modest amount of self-produced samples, while failing to find broader commercial success.

Léon-Josse Dassonville was born in Namur, Belgium, on December 25, 1887. Colloquially called Josse, he was raised and schooled mostly in Paris, working at the Société Pathé until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Serving in the cinematographic service of the Belgian army (SCAB), he was charged with filming on the frontline and capturing aerial footage. After the war, Dassonville returned to Saint-Gilles, Brussels, where, on October 16, 1919, he founded the company Établissements L.J. Dassonville, a laboratory for film development and printing that mostly delivered French-language intertitles for foreign silent films. When the laboratory burned down in March 1922, Léon-Josse, together with his brother Louis, constructed a modern film laboratory at rue Berthelot 135–141 in Forest, Brussels. There, Dassonville began his research into a natural color process. Between 1930 and 1936, he filed four patent applications. The first focused on the color printing process itself, and the second on the printing of the sound track simultaneously with the second color record. Two more patents, issued in 1932 and 1936, stated improvements to the process, including the expansion to a three-color system.

On December 14, 1934, Dassonville registered the company Société Anonyme Dascolor, capitalized for 600,000 Belgian francs, intended for the exploitation of the Dascolor process (Anon., 1935a: p. 30). The color process was in use from the summer of 1934, until the outbreak of World War II, when its exploitation ceased. In a 1966 interview, Léon Josse Dassonville explained that under American law the Dascolor patents had fallen into the public domain for the duration of the war and that he was unable to claim royalties (Anon., 1969: p. 17). Asserting that “the Americans shot millions of meters of color film using the Dascolor process”, he decided to confine the lab's post-war activities solely to developing and printing. (Anon, 1969: p. 17–18 [author's translation from French])

From its first results, the Dascolor process was marketed as a decidedly “Belgian” invention (Anon., 1934: p. 8). The color process was hailed as a testimony to the entrepreneurial efforts of Belgian captains of industry like Dassonville, who, in times of economic crisis, still “care enough about the country's reputation to dare to create a new industry” (Anon., 1935b: p. 5 [author's translation from French]). Also, film subjects such as Le défilé du 21 juillet (1934), with its flag parade on the Belgian National Day, and Ce que nos yeux ne verront plus (1935), of the Brussels World Fair of 1935, used an appeal to national pride to attract patrons and spectators. On December 15, 1936, Belgian director Gaston Schoukens organized a gala evening in the prestigious Cinema de l'Ermitage in Paris, to present the best of Belgian film production to the French public, “who hardly knows it exists” (Anon., 1936 [author's translation from French]). On the program were feature films by reputed filmmakers Henri Storck and Charles De Keukeleire, and short color films by Dassonville. Technical advances to the Dascolor process were suggested in a competitive spirit, in an article in the trade magazine Revue belge du cinéma:

“Did we know that Dassonville, constantly perfecting the Dascolor process, would soon be at the same point as the Americans? From the two-color process he used until now, our compatriot is now moving into three-color – and the film clips presented in Paris will be a revelation.” (Anon., 1936: p. 9 [author's translation from French])

Unfortunately, the only information on films employing this new Dascolor process comes from a B/W 16mm print of Tervuren, musée du Congo belge (Hélène Schirren, 1939) which credits the trichrome Dascolor process in its opening titles.

On December 16, 1955, Léon-Josse Dassonville was awarded the Medal of Chevalier in the Order of Leopold II by the Belgian Union of Cinematographers. He died, aged 88, on September 14, 1975. At the end of 1989, the company L. J. Dassonville, now headed by Josse's oldest son Jacques, was put into liquidation, 70 years after its incorporation. At some point, the Dassonville family deposited four short films printed in Dascolor at the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique – Cinematek, Brussels: Ce que nos yeux ne verront plus, Jolis contes de fées, Small Fish Fry, and an unidentified reel subsequently catalogued as [Côte d'Azur]. The laboratory buildings in rue Berthelot in Forest, Brussels, are still standing today, although they have been converted into lofts and apartments.

Selected Filmography

A one-reel report on the Brussels International Exposition of 1935, topped by a charming visit to “Royaume des enfants”, the local daycare service for children (Anon., 1935b: p. 5; Anon., 1935c: p. 13). A 35mm nitrate print, with a variable-area soundtrack spliced to a variable-density soundtrack, exists in the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique – Cinematek, Brussels.

A one-reel report on the Brussels International Exposition of 1935, topped by a charming visit to “Royaume des enfants”, the local daycare service for children (Anon., 1935b: p. 5; Anon., 1935c: p. 13). A 35mm nitrate print, with a variable-area soundtrack spliced to a variable-density soundtrack, exists in the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique – Cinematek, Brussels.

Short film that reports on the festivities on Belgium's National Day – specifically, the flag parade sequence was singled out for praise in the press. (Anon., 1934: p. 8; Anon., 1935c: p. 13)

Short film that reports on the festivities on Belgium's National Day – specifically, the flag parade sequence was singled out for praise in the press. (Anon., 1934: p. 8; Anon., 1935c: p. 13)

This dance film was reported in La cinégraphie belge, a weekly magazine for film professionals, where it was reportedly shown in a screening in the Dassonville laboratory to demonstrate the progress made in the Dascolor process. (Anon., 1935c: p. 13)

This dance film was reported in La cinégraphie belge, a weekly magazine for film professionals, where it was reportedly shown in a screening in the Dassonville laboratory to demonstrate the progress made in the Dascolor process. (Anon., 1935c: p. 13)

Accompanied by piano music, the actress Jane Smile sings short versions of fairy tales written by Charles Perrault, including Le petit poucet [Little Thumb], Le chat botté [Puss in Boots], La belle au bois dormant [Sleeping Beauty] and La barbe bleue [Bluebeard]. The Brussels’ Cinémathèque royale de Belgique holds a nitrate print, lasting four minutes.

Accompanied by piano music, the actress Jane Smile sings short versions of fairy tales written by Charles Perrault, including Le petit poucet [Little Thumb], Le chat botté [Puss in Boots], La belle au bois dormant [Sleeping Beauty] and La barbe bleue [Bluebeard]. The Brussels’ Cinémathèque royale de Belgique holds a nitrate print, lasting four minutes.

A tour of several picturesque spots on the French Riviera – from beach life in Cannes and Nice, to a boat trip in the Calanques, between Marseille and Cassis. A note on the film can indicates that the inspected print was copied from 16mm to 35mm. It is unclear when the copy was made.

A tour of several picturesque spots on the French Riviera – from beach life in Cannes and Nice, to a boat trip in the Calanques, between Marseille and Cassis. A note on the film can indicates that the inspected print was copied from 16mm to 35mm. It is unclear when the copy was made.

Named in the same article as the flag parade filmed on July 21, 1934, this color film was among the first to be released in Dascolor. (Anon., 1934: p. 8) Reportedly, this reel focused on colorful fabrics in motion, excellent subjects to demonstrate the accuracy and dynamic range of a new color process.

Named in the same article as the flag parade filmed on July 21, 1934, this color film was among the first to be released in Dascolor. (Anon., 1934: p. 8) Reportedly, this reel focused on colorful fabrics in motion, excellent subjects to demonstrate the accuracy and dynamic range of a new color process.

This ten-minute film presents the collection of small exotic fish at the Brussels public aquarium. Voiceover commentary is completed by music from Vladimir Launitz, Russian composer and conductor of ballet music. The Dascolor process is singled out in a separate title card that points out its local fabrication in Forest, Brussels.

This ten-minute film presents the collection of small exotic fish at the Brussels public aquarium. Voiceover commentary is completed by music from Vladimir Launitz, Russian composer and conductor of ballet music. The Dascolor process is singled out in a separate title card that points out its local fabrication in Forest, Brussels.

Documentary about the activities of the Museum of the Belgian Congo in Tervuren, Belgium. The film presents an inventory of what can be seen in the museum’s display cabinets as well as the museum’s scientific activities. This title only survives in a B/W 16mm reduction print, which credits the three-color Dascolor process.

Documentary about the activities of the Museum of the Belgian Congo in Tervuren, Belgium. The film presents an inventory of what can be seen in the museum’s display cabinets as well as the museum’s scientific activities. This title only survives in a B/W 16mm reduction print, which credits the three-color Dascolor process.

Technology

Dascolor was an unusual two-color process that was photographed using standard bi-pack negatives (two negatives sandwiched together in the film gate). All surviving Dascolor films were shot on Gevaert film. The Debrie bipack camera model or similar cameras equipped to expose bipack negatives were recommended.

Patents filed in 1930 describe an elaborate sequence of operations to create release prints, in which two successive exposures were made on the same side of a film strip. After the first color record from the bipack camera negative had been printed, developed and fixed in the ordinary way, the same emulsion coat was then resensitized in a chemical bath, upon which the second color record was exposed and developed. As the final positive color print was a single film strip, with only one emulsion layer containing both color records, it could be projected using existing projectors without alterations. In a 1966 interview, Dassonville also pointed out that final Dascolor projection prints have no grain (Anon., 1969: pp. 17–18).

The component colors of Dascolor were blue and orange. The first color record was printed in Turnbull's blue, or ferrous ferricyanide, through dye-toning, resulting from impregnating the emulsion in ferric chloride and oxalic acid for resensitizing after the first development and fixing. The immersion of the film strip in a solution of potassium ferricyanide converted the silver image to blue.

The second color record was printed in a coppery orange using dyes, resulting from washing the film in a solution of potassium iodide to mordant the silver of the first image before passing it through an aniline dye bath to color it orange.

The sound track was simultaneously printed with the second color record, and thus appears orange. Mono soundtracks in variable-area as well as variable-density were used, sometimes on the same film.

Press reviews signal significant progress in the color process by 1935 (Anon., 1935c: p. 13). Although no technical details were shared, "strong support from French technicians" is mentioned. Of particular note was the reasonable price, claimed to be only slightly higher than a regular B/W film, and the rapid delivery of release prints due to in-house shooting, development and printing, which was said to make Dascolor very suitable for actuality news reports. (Anon., 1935b: p. 5)

A press report from 1936 (Anon., 1936: p. 9) announced the development to a three-color Dascolor process, a possibility already anticipated on in the original 1930 patent by proposing to superimpose “a third image, in yellow for instance, by dye-impression or imbibition printing processes” (Patent 377,411, 1930, line 105). Indeed, the documentary Tervuren, Musée du Congo belge (Hélène Schirren, 1939), credits the Dassonville Laboratories for its print in “trichromies”. Unfortunately, the color elements are no longer extant, the Brussels’ Cinémathèque royale de Belgique only holds a B/W 16mm film copy.

References

Anon. (1934). “Une invention belge”. Revue belge du cinéma , 31 (Aug. 5): p. 8.

Anon. (1935a). “Dascolor, Société belge pour l'Exploitation des Procédés Dassonville”. Revue Belge du cinéma 6 (10 Feb. 1935): 30.

Anon. (1935b). “La Semaine”. Revue belge du cinéma, 37 (Sep. 15): p. 5.

Anon. 1935c. “Le progrès des films en couleurs”. La cinégraphie belge, 103 (Sep. 21): 13.

Anon. (1936). “Un gala de cinéma belge à Paris”. Revue belge du cinéma, 50 (Dec. 13): p. 9.

Anon. (1969). “Marginales”. Ciné dossiers, 14 (June): pp. 14–18

Cauda, Ernesto (1938). Il cinema a colori. Quaderno mensile, 2:11: p. 48. Roma: Bianco e nero.

Dassonville, Laure (n.d.). “Généalogie de la famille Dassonville: XVI Léon-Joseph-Jules-Oscar Dassonville-Mangin”. http://www.dassonville2.be/16-leon-mangin/16-leon-mangin.htm (accessed January 6, 2024).

Deckers, Ann (2000). “Dascolor: een vergeten Belgisch cinematografisch en fotografisch kleurenprocédé”. Unpublished Master's thesis, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp Belgium. https://anet.be/record/opacap/c:lvd:6531882/N.

Klein (Cornwell-Clyne), Adrian Bernhard (1940). Colour Cinematography (2nd rev. edn), pp. 210–11. Boston: American Photographic Publications.

Patents

Dassonville, Léon Josse. Improvements in Process of Preparing Coloured Photographic and Cinematographic Pictures. Belgian Patent 372003, filed July 16, 1930, and issued July 28, 1932.

Dassonville, Léon Josse. Improved Process of Preparing Cinematograph Films bearing Natural Colour Pictures and Sound Records. Belgian Patent 374932, filed November 13, 1930, and issued September 1, 1932.

Dassonville, Léon Josse. Deuxième perfectionnement au brevet d'invention no. 372003 du 16 juillet 1930. Belgian Patent 385904, and issued January 23, 1932.

Dassonville, Léon Josse. 1936. Troisième perfectionnement au brevet d'invention no. 372003 du 16 juillet 1930. Belgian Patent 415614, and issued May 18, 1936.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Hilde D'haeyere is a photographer and film historian who investigates photographic aspects of cinema. Much of her work is on film style, movie technology, and the mechanisms of humor, with a particular focus on silent slapstick comedy and early color strategies. As well as working as photographer of art and architecture, she currently lectures at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK), school of arts at the University College Ghent, Belgium, where she heads the master's program in film.

Thanks to Noël Desmet and Ann Deckers for making their research on Dascolor avalaible, and to Arianna Turci and Bruno Mestdagh, of Brussels' Cinémathèque royale de Belgique, for letting me inspect the extremely rare prints and for providing the illustrations.

D'haeyere, Hilde (2025). “Dascolor”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.