An additive three-color screen process, based on a photographic process originated by Louis Dufay. 35mm Dufaycolor prints were made for theatrical exhibition using two methods: reversal original to reversal print; and negative to print.

Film Explorer

Title frame from a Dufaycolor reversal print (printed from a Dufaycolor reversal original), Fox Movietone News’ King’s Jubilee in Color (1935).

Earl I. Sponable papers, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, New York, NY, United States.

A 35mm print of Sons of the Sea (1939) made from a Dufaycolor negative. This was the only feature-length film made entirely in Dufaycolor.

Film Technology Frames Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

The 35mm Dufaycolor camera negative for Sons of the Sea (1939) on acetate stock.

BFI National Archive, Berkhamsted, United Kingdom.

Identification

Panchromatic B/W emulsion (made by Ilford) exposed through a three-color mosaic pattern (réseau) in the base. Initially, reversal prints were made directly from reversal camera positives. Later films were made on Dufaycolor camera negative and prints were made from these.

Reversal prints had black edges, while negative-positive prints had clear edges, although the réseau pattern was visible. Footage numbers are sometimes printed-through on the edge in white text.

According to some sources, cellulose triacetate may also have been used and cellulose nitrate film was considered being used after World War II.

1

Full color, with subtle muted tones.

Print: Dufaycolor; A Dufaycolor Picture; Photographed by Dufaycolor; On Dufaycolor

Optical sound on 35mm release prints. Compatible with both variable area and variable density sound. The réseau was visible within the soundtrack area but reportedly did not interfere with sound quality.

Panchromatic B/W emulsion (made by Ilford) exposed through a three-color mosaic pattern (réseau) in the base.

Unknown

History

Originally developed for photographic glass plates by Louis Dufay in the early 1900s, the rights to the Dufaycolor three-color screen process were purchased in 1926 by Spicer Ltd, Cambridge, England. As manufacturers of paper and film products, including cellulose acetate wrapping material, they were aware of the growth of “safety” film in the motion picture industry, their intent was to refine the process to create a viable natural color motion picture stock. (See Dufaycolor (reversal) for more about the company’s history).

Engineers T. Thorne Baker, who had previously worked with Louis Dufay in France, and Charles Bonamico were hired to carry out extensive research and refinements to the manufacturing of the color screen (called the réseau – the French for “network” or “grid”). Later that year, Dufay, Baker, and Bonamico shot several thousand feet of 35mm negative in the south of France on 8-lines per mm réseau which they then printed on 15-lines per mm réseau. The results revealed the technical difficulties of the negative-positive process such as “color dilution” and moiré patterns in the prints (Baker, 1938: p.244). Further refinements to the réseau resulted in an improved 20-lines per mm print, which was demonstrated in 1931 at the Royal Society in London and at the British Kinematograph Society. At the time, the process was known as Spicer-Dufay. But problems with color saturation and moiré patterns in the positive prints persisted.

On April 20, 1934, Dufaycolor Ltd, as the company was now known, publicly demonstrated 35mm and 16mm Dufaycolor reversal stock at the Savoy Hotel in London. The company’s initial primary interest had been to develop a viable color process for the motion picture industry, particularly as a competitor to Technicolor, but given the still-unresolved issues with duplicating the stock for release prints – essential for theatrical film distribution – the focus turned to marketing the reversal stock while solutions to the printing process were explored.

Dufaycolor 16mm reversal film was launched in the UK in late summer of 1934, particularly targeting amateur and non-theatrical filmmakers. However, a number of 35mm theatrical releases made somewhat successful use of the reversal process. The release in late 1934 of Radio Parade of 1935 – released in the US as Radio Follies – included two dance numbers filmed in the Dufaycolor reversal process by Claude Friese-Greene and printed as reversal prints for theatrical release. In 1935, British Movietone News filmed King George V’s Silver Jubilee celebrations using Dufaycolor 35mm reversal process. Several other 35mm shorts soon followed including Len Lye’s innovative A Colour Box for the General Post Office (UK, 1935), in which he painted directly onto clear film stock before being printed on Dufaycolor reversal stock.

Building on the many improvements made to the duplication process (detailed in the Technology section below), in 1937 Dufay-Chromex -- the company had merged the previous year with Chromex, a holding company for the takeover of British Cinecolor (Street, 2012: p. 270) -- hired Adrian Klein (later known as Cornwell-Clyne), an expert in color photo chemistry, from Gasparcolor to lead further research and development. Under Klein’s leadership, Dufay-Chromex formed a production company and commissioned documentary filmmaker Humphrey Jennings to make three short films. The improved negative-positive process along with Klein’s appointment opened the door for more commercial opportunities. Without the need for excessively complicated cameras or additional accessories, Dufaycolor was particularly attractive to documentary filmmakers, advertising companies and artists wanting to experiment with color. In the pre-war years, over 50 short films and commercials were made using the negative-positive process, with works from notable filmmakers such as Mary Field, Percy Smith, and J. V. Durden for their Secrets of Life series (1939); Lotte Reiniger (Heavenly Post Office, 1938); and Norman McLaren (Love on the Wing, 1938). Pathé Gazette filmed King George VI’s coronation in 1937 using Dufaycolor, and in 1939, the only feature-length Dufaycolor film, Sons of the Sea was released.

Even though all Dufaycolor film was manufactured exclusively in the UK, laboratories were equipped to process Dufaycolor film in Paris, Geneva, Rome, Johannesburg, Bombay [Mumbai] and Barcelona (Cornwell-Clyne, 1951: p. 22). Interest in Dufaycolor extended to filmmakers around the world, with productions such as Parures in Switzerland (Werner Dressler, 1939), Garden of Tasmania (Frank Hurley, 1938/39?), Roumania (unknown, 1937) and Follow the Sun, shot in Madeira (Ronnie Haines, 1940). Reportedly, one filmmaker who was using Dufaycolor negative to film in Tunis, Tunisia, was arrested and imprisoned for shooting what was believed to be prohibited matter, and the material was subsequently never allowed to be shown. (Brown & Cornwell-Clyne, 1956)

Despite the engineering ingenuity, photochemical expertise and the extensive investment of time and money, Dufaycolor began losing traction in both the industry and amateur markets to subtractive processes such as Technicolor and Kodachrome. The many technical disadvantages with additive processes like Dufaycolor – brighter lighting conditions needed for filming, ongoing difficulties duplicating prints, visible pattern of the réseau when projected – contributed to its commercial downfall. In 1938, Ilford began backing out of its investment in Dufay-Chromex, selling its shares and terminating its agreement completely by September 1939. Despite this, Ilford did continue to apply emulsion to the réseau base until Dufaycolor production ceased years later.

World War II forced a hiatus in research and production, and when work resumed, it had become clear that rival subtractive processes would be the future for both the industrial and amateur markets. Recognizing this, Dufay-Chromex shifted its research and development focus, investing in the pursuit of its own subtractive process as a rival to Technicolor (see Dufaychrome/British Tricolour). The production of film for the stills photographic market continued, both color and B/W, with operations finally ceasing in 1955. In January 1956, Adrian Cornwell-Clyne and Harold Brown oversaw the donation of Dufay-Chromex’s films to the British National Film Archive.

Selected Filmography

A two-reel short documenting a Royal visit to Ottawa. Per the local press: “It is a very striking job, though the first day’s activities, filmed in the rain, are preponderantly blue. […] Second day’s activities, particularly the trooping of the color, is particularly effective and striking.” (Young, 1939: p. 25)

A two-reel short documenting a Royal visit to Ottawa. Per the local press: “It is a very striking job, though the first day’s activities, filmed in the rain, are preponderantly blue. […] Second day’s activities, particularly the trooping of the color, is particularly effective and striking.” (Young, 1939: p. 25)

An anti-fascist propaganda film warning the citizens of Britain against being ignorant to the atrocities and cultural annihilation happening in Europe. Made for the Polish Film Unit in London by Polish avant-garde husband and wife filmmakers.

An anti-fascist propaganda film warning the citizens of Britain against being ignorant to the atrocities and cultural annihilation happening in Europe. Made for the Polish Film Unit in London by Polish avant-garde husband and wife filmmakers.

An abstract direct animation (the images are drawn/painted directly onto the film itself) commissioned by the UK General Post Office.

An abstract direct animation (the images are drawn/painted directly onto the film itself) commissioned by the UK General Post Office.

A short documentary featuring the Grand Steeplechase de Paris and the Cadre Noir military riding instructors of the French National Riding School.

A short documentary featuring the Grand Steeplechase de Paris and the Cadre Noir military riding instructors of the French National Riding School.

A short film featuring Norman Hartnell fashions being designed and modelled.

A short film featuring Norman Hartnell fashions being designed and modelled.

The first feature color animation made in Europe. Negative-positive process. (The film was later reissued in Hispanoscope with Eastmancolor prints.)

The first feature color animation made in Europe. Negative-positive process. (The film was later reissued in Hispanoscope with Eastmancolor prints.)

A color newsreel of King George V’s jubilee celebrations, distributed in the UK and US. Reversal print process.

A color newsreel of King George V’s jubilee celebrations, distributed in the UK and US. Reversal print process.

The last scenes of this feature film about Italian glider pilots in the Spanish Civil War are in Dufaycolor.

The last scenes of this feature film about Italian glider pilots in the Spanish Civil War are in Dufaycolor.

A musical feature with two color sequences in an otherwise B/W film. Reversal print process.

A musical feature with two color sequences in an otherwise B/W film. Reversal print process.

A Telugu social reformist film inspired by peoples' agitations against the zamindari system in pre-independent India Includes some scenes in Dufaycolor.

A Telugu social reformist film inspired by peoples' agitations against the zamindari system in pre-independent India Includes some scenes in Dufaycolor.

The only feature film made entirely in Dufaycolor. Negative-positive process.

The only feature film made entirely in Dufaycolor. Negative-positive process.

One of the last documented Dufaycolor releases. Negative-positive process.

One of the last documented Dufaycolor releases. Negative-positive process.

Technology

Dufaycolor prints were made by two methods: as a direct positive reversal print from a camera reversal original (c. 1934–37), or as a print made from a negative (c. 1936–49). Both methods used Dufaycolor stock with its réseau in the film base and emulsion applied by Ilford. For more information see: Dufaycolor (reversal).

Having worked for Dufay, Adrian Klein (later Cornwell-Clyne) provided detailed explanations of how the Dufaycolor negative-positive process worked in his book Colour Cinematography. Dufaycolor negative stock was available in two types: I. N. for daylight or high-intensity arc-lamps, and I. G. for incandescent filament lamps. (Cornwell-Clyne, 1951: p. 307) When using the appropriate stock for the lighting conditions, no additional correction filters were needed. As with the reversal stock, the panchromatic emulsion was applied by Ilford. However, Cornwell-Clyne does mention a reversal positive print test which was processed in the United States with emulsion coated by Dupont (Brown & Cornwell-Clyne, 1956). Although improvements were made to the emulsion’s speed (it was about half that of standard B/W panchromatic film), the amount of light absorbed by the réseau when filming and projecting remained problematic. In a leaflet “Notes for Projectionists”, which was distributed to theater projectionists, Dufay-Chromex technicians explained the additional care and attention needed to handle, join, and project Dufaycolor film. It noted that Dufaycolor would need “the maximum illumination you can obtain from your apparatus”. The visibility of the réseau when films were projected was also an issue. In order for the réseau to resolve or become unnoticeable, Dufay-Chromex recommended a distance of 60 ft (18.29m) away from a 25-ft (7.62m) screen, but Cornwell-Clyne claims it was invisible at as little as 30 ft (9.14m) away. He also observed that, “the original appearance of Dufaycolor was disappointing”. He observed that the reversal prints of Radio Follies and Silver Jubilee “suffered from a granular effect” known as “boiling”. (p. 21)

Experiments with a projection printing method had proved inferior. When asked at the Society of Motion Picture Engineers meeting, spring 1934, Atlantic City, NJ, whether the prints he had shown were made by contact or projection printing, Dr W. H. Carson – then vice president of Dufaycolor, Inc. – stated that it was by “projection” but they were not ready to discuss the method, for patent reasons. Carson admitted that the duplicates were not as good as the original (Carson, 1934).

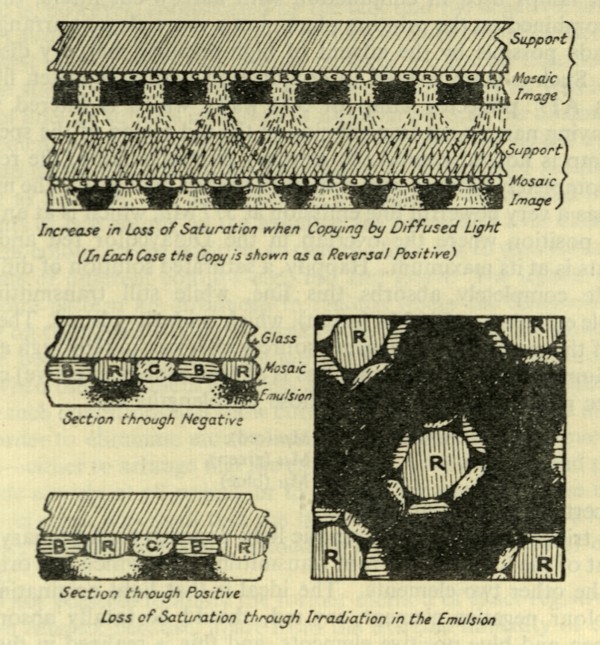

Work to refine and improve both the reversal and negative-positive processes continued amid competition in both the amateur and theatrical markets. A turning point in the negative-positive process came for the company – now renamed Dufay-Chromex – with the addition of chemist Dr D. A. Spencer’s depth developer in 1936 which, “made negative-positive processing practicable, since the restriction of development to the layer of emulsion in immediate contact with the réseau reduced spreading of the image with its consequent desaturation […] . Furthermore, the work of Dr. G. B. Harrison and Mr. R. G. Horner of Ilford Ltd, led to great improvements in the illumination system of contact printing machines, moiré patterns being completely eliminated”. (Cornwell-Clyne, 1951: p. 21) The Ilford team – which also included E. T. Purslow and S. D. Threadgold (Hercock, 1979: p. 65) – was at that time under the direction of Dr F. F. Renwick, head of research. Largely as a result of the Ilford team’s work on eliminating the moiré, contact printing proved to be the more satisfactory printing method. Cornwell-Clyne describes the team’s work in great detail (1951: p. 292–300). Dufay-Chromex invested in a new printing lab at Thames Ditton, England, with Vinten printers to handle the negative-positive printing.

Optical sound could be added to 35mm Dufaycolor prints. W. H. Carson noted in his address to the Society of Motion Picture Engineers in the spring of 1934 that: “Sound has been recorded on all the standard systems, including the Movietone News camera, wherein a sound record was taken, through the réseau, on the same film as that used for the picture.” (1934: p. 25)

In September 1935, in his address to the British Kinematograph Society, G. B. Harrison explained that the method for adding the soundtrack to a reversal print was “roundabout” because the original soundtrack negative had to first be printed to a positive before it could be applied to the reversal print. The density of the reversal print also meant that theater projectionists were required to increase the volume by about three points. Cornwell-Clyne noted that: “The sound track is printed on the emulsion side of the film by a normal sound-printing machine. Sound track has been quite successfully recorded on Dufaycolor negative. Even when recorded through the réseau, the quality is good enough for news films.” (1951: p. 306) With improvements made to the negative-positive process, less adjustment was needed and projectionists were advised that it may only be necessary to turn the fader up by one point. An information leaflet for projectionists noted that: “Although the background to the sound track may appear upon superficial inspection to be very dense, it is found in practice that it is never necessary to put the fader up more than one point to obtain the correct volume output.” (Dufay-Chromex, c.1937)

The variety of materials listed by Cornwell-Clyne and Brown in the Dufay-Chromex collection in 1956 (sadly, many of which are no longer extant) demonstrates the broad extent of testing and experimentation. The collection included several duplication/print tests such as a color balance test by dying the finished print (no date), back projection (1938) (“useless!” noted Cornwell-Clyne), a blown-up duplicate negative from 16mm Kodachrome (no date), a projection print from reversal original with use of rotating prism to diffuse the image of the réseau (1936), and a reversal duplicate made by contact printing from original reversal (1936). But ultimately, none were able to compete in the commercial market with the subtractive processes.

Prints were made by contact printing the original Dufaycolor camera film onto a Dufaycoior positive. During development, the depth developer (invented by D. A. Spencer in 1936) “restricted the lower level of the emulsion layer in immediate contact with the réseau. This eliminated desaturation due to irradiation and réseau image-element spread.” (Cornwell-Clyne, 1951: p. 290)

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography (3rd rev. edn). London: Chapman and Hall, p. 291.

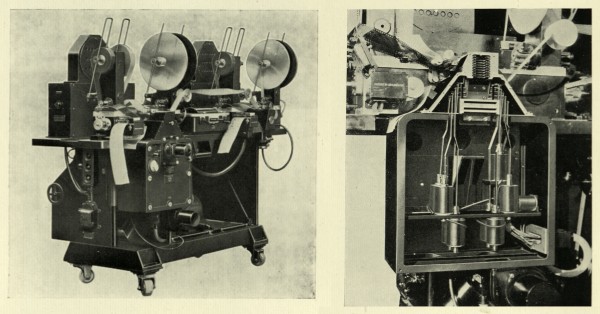

The Vinten-Dufaycolor 35mm film printer used to create Dufaycolor prints.

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography (3rd rev. edn). London: Chapman and Hall, pp. 300–01.

References

Baker, T. Thorne (1932). “The Spicer-Dufay color film process”. Photographic Journal, 72:109: pp. 109–17

Baker, T. Thorne (1938). “Negative-Positive with the Dufaycolor Process”. Journal of the SMPE, 31:3 (Sept.): pp. 240–7. https://mediahist.org/reader.php?id=journalofsociety31socirich (accessed August 17, 2024)

Brown, Harold & Adrian Cornwell-Clyne (1956). “[Films Received from Dufay Ltd on Monday 23 and Tuesday 24 January 1956]”. Unpublished notes.

Brown, Simon (2002). Dufaycolor: the Spectacle of Reality of British National Cinema. Centre for British Film and Television Studies. www.bftv.ac.uk/projects/dufaycolor.htm (accessed August 17, 2024).

Carson, W. H. (1934). “The English Dufaycolor Film Process”. Journal of the SMPE, 23:1 (July): pp. 14–26. archive.org/details/journalofsociety23socirich/page/14/mode/2up (accessed August 17, 2024).

Cornwell-Clyne, Adrian (1951). Colour Cinematography (3rd rev. edn). London: Chapman and Hall.

Coote Jack H. (1993). The Illustrated History of Colour Photography. Surbiton: Fountain.

Dufay-Chromex Ltd (c.1937). Notes for Projectionists. Thames Ditton, Surrey: Dufay-Chromex Ltd.

Filmcolors.org (n.d.). “Timeline of Historical Film Colors, Dufaycolor. https://filmcolors.org/timeline-entry/1257/ (accessed August 17, 2024).

Harrison, G. B. (1935). “Dufaycolor”. Proceedings of the British Kinematograph Society, 33 (September): pp. 3–7.

Hercock, Robert J. & George A. Jones (1979). Silver by the Ton: The History of Ilford Limited, 1879-1989. London: McGraw-Hill

Howe, Bryan (2002). The Dufaycolor Story: One of Britain’s Past Industries. Sawston: Link Publishing.

Ormes Ian (1997). From Rags to Roms: A History of Spicers 1796–1996. Cambridge: Granta Editions.

Street, Sarah (2012). Colour Films in Britain. The Negotiation of Innovation 1900–55. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Welford, S. F. W. (1988). Dufaycolor. History of Photography (January/March): pp. 31–5.

Young, Roly (1939). “Rambling with Roly”. The Globe and Mail (June 26): p. 25.

Patents

Dufay, Louis; Compagnie d’Exploitation des Procédés de Photographie en Couleurs Louis Dufay. Improvements in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB217557, filed April 16, 1924, and issued February 26, 1925.

Thorne Baker, Thomas. Improvement in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB324,43, filed August 8, 1928, and issued January 8, 1930.

Spicers Ltd; John Naish Goldsmith; T. Thorne Baker; Charles Bonamico. Improvements in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB333865, filed June 1, 1929, and issued August 21, 1930.

Goldsmith, John Naish; Spicer Ltd. Improvement in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB334243, filed May 30, 1929, and issued September 1, 1930.

Thorne Baker, Thomas; Dufaycolor Limited. Improvement in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB420824, filed June 6, 1933, and issued December 6, 1934.

Spencer, Douglas Arthur. Improvement in or relating to Colour Photography. British patent GB470855, filed January 23, 1936, and issued August 23, 1937.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Louisa Trott is a graduate of the University of East Anglia’s film archiving master’s program and has worked with small-gauge and amateur film collections at regional and national film archives in the UK and US. In 2005, she co-founded the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound in Knoxville. Since 2021, she has been Arts & Humanities Librarian and Associate Professor at the University of Tennessee.

Thank you to all who have shared their knowledge and collections of Dufaycolor with me over the years, but the biggest thanks go to David Cleveland and Jane Alvey who encouraged me to dive deeper into Dufaycolor history through its East Anglian connections. Thanks too to Iyesha Geeth Abbas and Bhavesh Singh at the National Film Archive of India who shared information about Rythu Bidda (1939).

Trott, Louisa (2024). “Dufaycolor (prints)”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.