A subtractive, three-color chromogenic reversal film, used in 16mm for motion pictures, and in 35mm for still photography.

Film Explorer

Unidentified, c. 1950s. 16mm Anscochrome reversal camera original.

Kodak Film Samples Collection, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom. Photograph by Josephine Diecke, Film Colors. Technologies, Cultures, Institutions (SNSF project), and Joëlle Kost, FilmColors (ERC Advanced Grant), courtesy of The Timeline of Historical Film Colors, https://filmcolors.org/galleries/anscochrome-samples-kodak-film-samples-collection/

[Home Movie – Beller Family – Altman's Windows #2, Christmas, 1960] (1960). The edge marking, “ANSCO SAFETY 226”, indicates this is Super Anscochrome (Tungsten Balanced), which was released in 1958, following the release of Super Anscochrome (Daylight) in 1957. The initials “PNI” mean, “Processing Not Included” – after buying and exposing the film, the customer would need to pay extra for processing.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

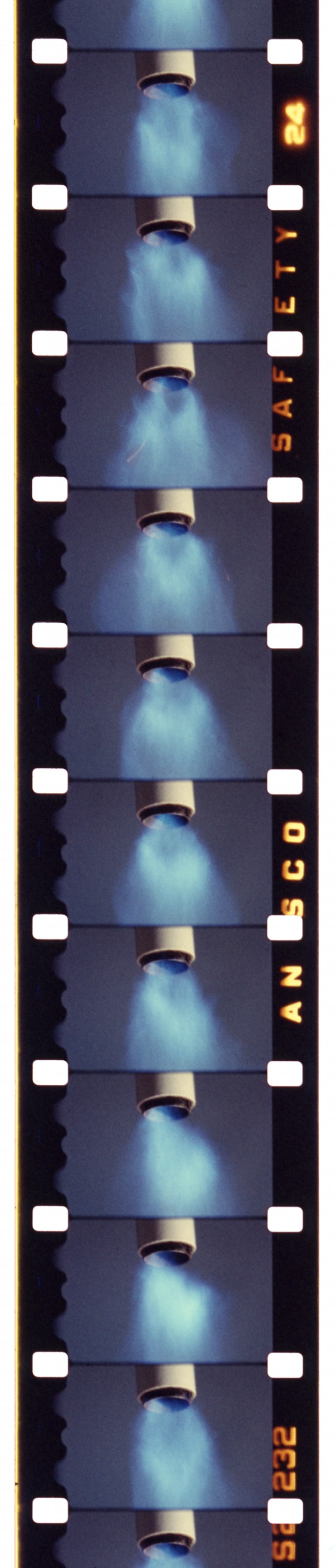

Unedited 16mm footage, shot by documentary filmmaker Francis Thompson in the late 1950s. The edge marking, “ANSCO SAFETY 232”, indicates this is the first version of Anscochrome (Tungsten Balanced), which was released in 1955.

Francis Thompson Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

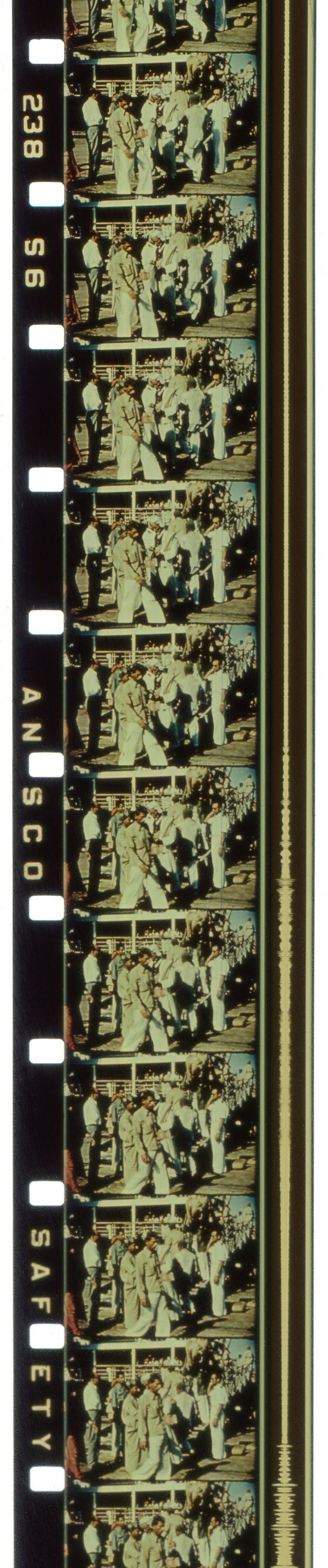

A 16mm reversal print, with a brown sulfide soundtrack, of Pakistan, Its Land and Its People (1955), on Anscochrome 238 print stock, introduced in 1955.

Courtesy of Paul Ivester.

Identification

Anscochrome 238 (1955); Anscochrome 244 (1959).

"ANSCO SAFETY” spaced between perforations.

1

Good color stability.

Either silent, magnetic stripe, or optical. 16mm Anscochrome camera film for amateur use was silent, or had a magnetic soundtrack. Optical sound on 16mm print film was sometimes used for professional work – this required a special development process, which converted the silver halide in the soundtrack to silver sulfide, giving it a brown color.

(35mm for still photography only)

All Anscochrome products are reversal film. Emulsions evolved over time with a particular focus on film speed. Anscochrome 231 (1955–63); Super Anscochrome 225/226 (1957); Anscochrome Professional 238 (1956–63); Anscochrome Professional Film 242 (1957–66); Anscochrome 50 (1963–68); Anscochrome 100 (1965–68); Anscochrome 200 (1965–76). (Note: the 8mm formats Anscochrome II (1967–68) and IIA (1967–71) did not use the standard Anscochrome emulsion and process. They were developed using the Kodachrome K-11 process.)

“ANSCO SAFETY [3-digit emulsion type number | 3-letter code]” on 16 mm. After 1967, some stocks likely used “GAF SAFETY”.

History

Anscochrome, a subtractive, integral tripack (three-emulsion-layer) color film, was introduced in 1955 by the Ansco Company of Binghamton, New York. It was used in 16mm by amateurs, as well as by professionals for commercial, industrial, educational, and similar non-theatrical purposes. Anscochrome was based on the process developed by the German company Agfa – released in 1936, as Agfacolor Neu. Like Agfacolor Neu, Anscochrome was a reversal film, meaning the camera emulsion was developed directly into a positive during processing. As such, it was difficult to duplicate in quantity, and was not well-suited to feature-film work. The company also sold Anscochrome in 35mm – but only for use in still photography.

Anscochrome competitors included Eastman Kodak's Kodachrome, also an integral tripack reversal film; introduced in 1935, one year before the release of Agfacolor Neu. Anscochrome, like Agfacolor Neu, included color couplers in the film itself; while Kodachrome added the couplers during processing. This enabled a far simpler development process for Anscochrome and its predecessors. For amateurs, and small independent labs, Kodachrome was very difficult to process – indeed, in the years before 1954, Kodak required that exposed Kodachrome film was mailed back to the company, for processing. By the 1960s, Kodak’s Ektachrome, an integral tripack reversal film that included couplers in the film itself, became available in small gauges for movies, and soon dominated the market.

The Ansco company's antecedents go back to the E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., a successful American photographic supply company, started soon after the invention of the Daguerreotype. A merger with Scovill and Adams Co., in 1902, was followed by the adoption of the Ansco name a few years later. However, by the 1920s, inefficient manufacturing, poor management and inadequate research capability at the company had led to financial difficulties (Jenkins, 1975: p 337), which necessitated that Ansco look for another partner, if they were to survive. Ansco merged with the German company Agfa in 1928, to form Agfa-Ansco Photo Products Co. The merger brought an influx of German scientists, technicians, equipment, and capital (Wentzel,1960: p. 101), as well as “access to its all-important scientific and technical research facilities in Germany” (Jenkins, 1975: p 337). It was at the Agfa facilities in Wolfen, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany, that Wilhelm Schneider developed Anscochrome's ultimate progenitor, Agfacolor Neu, in 1936. The Agfa-Ansco company was seized by the US Treasury Department at the beginning of World War II and “Agfa” was dropped from the name; this gave the Agfa company the freedom to operate independently within Germany. Ansco developed Ansco Color Reversal film, a 16mm American version of Agfacolor reversal film, in 1941, at the request of the US military. It was made available to the public after the war.

In 1955, Ansco Color Reversal film was rebranded as Anscochrome. Its high speed – ASA 32 was three times faster than existing Ansco Color and Kodachrome – was featured as a unique selling point in advertising and reviews. It was available in 16mm, for both daylight, and artificial light (Tungsten Balanced). Subsequent versions increased speed and reduced granularity.

Anscochrome 231 (Daylight Balanced) and 232 (Tungsten Balanced), introduced in 1955. The first Anscochrome movie films were rated at ASA 32, at a time when Ansco Color Reversal film was rated at ASA 12, and Kodachrome at ASA 10.

Super Anscochrome 225 (Daylight Balanced) and 226 (Tungsten Balanced), introduced in 1957 for 16mm, was three times faster again than the initial 1955 version. Rated at ASA 100, it made shooting in available light (natural and artificial) possible for amateurs. (Schwalberg, 1957; Cushman ,1957: p. 802).

Anscochrome Professional Film 242 and 238 Duplicating Film were released in 1957 to address the professional need for multiple movie prints, which required a lower contrast camera film (Forrest, 1957: pp. 12–13).

FPC-132 was created in 1961 for NASA: this variant was used to film Alan Shepherd in the Mercury capsule during his historic space flight on May 5, when he became the first American to travel into space (Press and Sun-Bulletin, 1961). Rated at ASA 200, it was later marketed as Ultra-Speed Anscochrome, for scientific and engineering use, and in 1963, as Anscochrome 200, for commercial and amateur use. (Press and Sun-Bulletin, 1967).

Note: Although they share the Anscochrome name, Anscochrome II and IIA (1967–77) were 8mm consumer films that employed the Kodachrome process (K-11), not the Anscochrome process.

In 1977, unable to compete with Eastman Kodak, GAF finally withdrew from the consumer photography market, at which time manufacturing in Binghamton shut down (Carnevale & Spero, 1977).

16mm Anscochrome packaging, c. 1960. Test reel, shot by British amateur filmmaker H. A. V. Bulleid.

East Anglian Film Archive, Norwich, United Kingdom.

In 1967, Ansco was rebranded as GAF after its parent company General Aniline & Film. From this date, until its discontinuation in 1976, Anscochrome 200 reversal film likely featured “GAF SAFETY” edge markings.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Selected Filmography

Filmed on FPC-132 (ASA 200) – which was eventually marketed as Anscochrome 200.

Filmed on FPC-132 (ASA 200) – which was eventually marketed as Anscochrome 200.

A 16mm home movie filmed on Super Anscochrome 226 camera reversal film. Conserved at George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

A 16mm home movie filmed on Super Anscochrome 226 camera reversal film. Conserved at George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

An educational film distributed on 16mm Anschrome 238 reversal print stock.

An educational film distributed on 16mm Anschrome 238 reversal print stock.

Technology

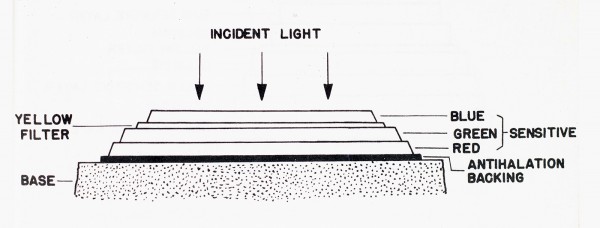

Anscochrome was a reversal camera and print film. Like Ansco Color and Agfacolor, it was an integral tripack film (first described by Karl Schinzel, in 1905 [Friedman, 1945: p. 406]), meaning that the blue-, green- and red-sensitive emulsions were stacked in layers, on one side of the film base. The layers were thin enough that the overall film thickness was comparable to standard B/W film. This was a key advantage of integral tripack films: they could be exposed and projected using standard cinema equipment.

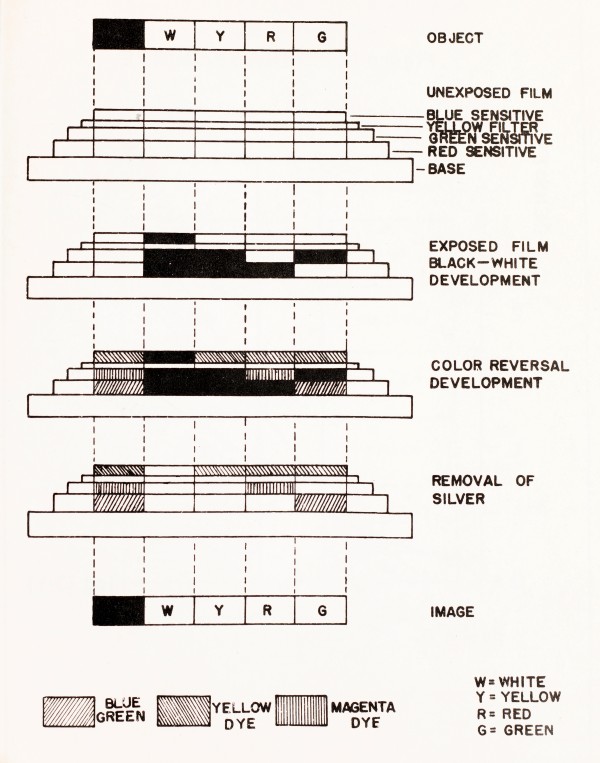

The top layer was a standard silver halide emulsion, sensitive to blue, by default. The second and third layers contained silver halide sensitized to green, and red, respectively. Each layer also contained a color coupler, a chemical that created a dye when it combined with the oxidation products produced in the development of exposed silver halide grains. The use of color couplers embedded in the film emulsion was patented by Rudolph Fischer in 1912 (BP 15,055/1912). Unfortunately, Fischer was unable to prevent the couplers from diffusing, and contaminating the other layers. This issue was resolved in the 1930s, by Wilhelm Schneider and Gustav Wilmanns at the Agfa laboratories in Wolfen, Germany, by attaching chains of carbon atoms to the coupler to anchor it (Schneider, 1947: pp. 20–6). Schneider's process was “a commercial realization of Fischer's process” (Mathews, 1955: p. 115), and was released in Germany as Agfacolor Neu in 1936 (later called simply Agfacolor). The same process was later used for both Ansco Color and Anscochrome.

The fact that the dye couplers were contained within the emulsion layers was a key advantage of Agfa's process. The Kodachrome process, introduced by Kodak in 1935, added the color couplers later, during the process of developing the film – a complex operation that, until 1954, required the user to return exposed film to Kodak for processing. The simpler Agfacolor (and, hence, Anscochrome and Ansco Color) reversal process, allowed film to be developed at home, or in smaller labs.

Although most amateur 16mm films were silent, or used magnetic soundtracks, optical soundtracks were sometimes used for professional 16mm. Optical soundtracks required special handling for reversal film. The standard dye-based reversal process left a soundtrack that was transparent to red/infrared – inefficient for the caesium-type phototubes used in commercial projectors. The solution adopted by Ansco was to convert the silver halides in the soundtrack to silver sulfide, leaving a soundtrack opaque to red/infrared (Forrest, 1949: p. 40).

The emulsion layers of an integral tripack film. The yellow-filter layer prevented any blue light that leaked through the first layer from reaching the green and red layers – this was important, since the silver halide in these layers was also sensitive to blue. The antihalation backing prevented light from bouncing back off the base and fogging the emulsion layers.

Schneider, Wilhelm (1947). The Agfacolor Process: Fiat Final Report No. 976. Office of Military Government, United States (Amt der Militärregierung für Deutschland (U.S.)).

The stages of Agfa/Ansco color reversal processing. 1) The three layers are exposed and developed using a standard B/W developer, leaving metallic silver as a B/W negative in each layer; unexposed silver halide is left in the emulsion. 2) The layers are re-exposed to white light, which exposes the remaining silver halide; a color developer is applied, which activates the color couplers in each layer, creating the colored dyes. 3) The metallic silver in all three layers is removed, leaving the dyes that create the subtractive colors corresponding to the original colors of the scene.

Schneider, Wilhelm (1947). The Agfacolor Process: Fiat Final Report No. 976. Office of Military Government, United States (Amt der Militärregierung für Deutschland (U.S.)).

References

Anon. (1962). Advertisement. Press and Sun-Bulletin (February 21): p. 55. Binghamton, NY, United States.

Carnevale, Marylu & Stever Spero (1977). "GAF Closing Cuts 1100 Jobs”. The Evening Press (July 22): p. 1. Binghamton, NY, United States.

Cushman, George W. (1957). “Now You Can Shoot Color Anywhere”. American Cinematographer, 38:12 (December): pp. 802–3, 816.

Duerr, H. H. & H. C. Harsh (1946). “Ansco Color for Professional Motion Pictures”. Journal of the SMPE, 46:5 (May): pp. 357–67.

Enticknap, Leo (2005). Moving Image Technology from Zoetrope to Digital. London: Wallflower Press.

Forrest, J. L. & F. M. Wing (1937). “The New Agfacolor Process”. Journal of the SMPE, 28:5 (May): pp. 561–2.

Forrest, J. L. (1949). “Metallic-Salt Track on Ansco 16-mm Color Film”. Journal of the SMPE, 53:1 (July): pp. 40–9.

Forrest, J. L. (1955). “Processing Anscochrome motion-picture film for industrial and scientific applications”. Journal of the SMPTE, 64:12 (December): pp. 679–81.

Forrest, J. L. (1957). “A new 16mm camera color film for professional use”. Journal of the SMPTE, 66:13 (January): pp. 12–13.

Forrest, J. L. (1958). "16mm Super Anscochrome Films". Journal of the SMPTE, 67:10 (October): pp. 691–3.

Friedman, Joseph Solomon (1945). History of Color Photography. Boston: The American Photographic Publishing Company.

Jenkins, Reese V. (1975). Images and Enterprise: Technology and the American Photographic Industry. Baltimore, MA: The John Hopkins University Press.

Koshofer, Gert (2010). “Jahre farbige Schmalfilme – und schon früher”. Hamburger Flimmern, 17 (November): pp. 14–21.

Lipton, Lenny (2021). The Cinema in Flux. New York: Springer Publishing Co.

Mathews, Glenn E. & Raife G. Tarkington (1955). “Early History of Amateur Motion-Picture Film”. Journal of the SMPTE, 64:3 (March): pp. 105–16.

Merritt, Russell (2008). “Crying in Color. How Hollywood Coped When Technicolor Died”. Journal of the National Film and Sound Archive [Australia], 3: 2/3: pp. 1–16.

Press and Sun-Bulletin (1961). “Scientists ‘Accompany’ Shepard in Grueling Flight at Ansco Film Showing”. Press and Sun-Bulletin (May 25): p. 21. Binghamton, NY, United States.

Press and Sun-Bulletin (1967). “Ansco New, Fast Color Film to be Available Very Soon”. Press and Sun-Bulletin (Mar. 13): p. 15. Binghamton, NY, United States.

Schneider, Wilhelm (1947). The Agfacolor Process: Fiat Final Report No. 976. Office of Military Government, United States (Amt der Militärregierung für Deutschland (U.S.)).

Schwalberg, Bob (1957). “ Report on the Fastest Films Yet – Super Anscochrome and Royal-X Pan”. Popular Photography. (June): pp. 74, 125.

Wentzel, Dr. Fritz (1960). Memoirs of a Photochemist. Philadelphia, PA: American Museum of Photography.

Patents

Fischer, Rudolph. Production of Photographs in Natural Colours. British Patent 15,055, issued June 27, 1912.

Schneider, Wilhelm. Manufacture of Multicolor Photographs. US Patent 2,179,234, filed Sept 11, 1936, and issued Nov 7, 1939.

Compare

Related entries

Author

John Wallace is a collector of film and other media. In his professional life he was a user experience designer for the software company Autodesk. He lives in Ithaca, NY.

Thanks to Ken Fox at the Richard and Ronay Menschel Library at the George Eastman Museum for help finding Ansco materials.

Wallace, John (2025). “Anscochrome”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.