An anamorphic widescreen process developed at Twentieth Century-Fox.

Film Explorer

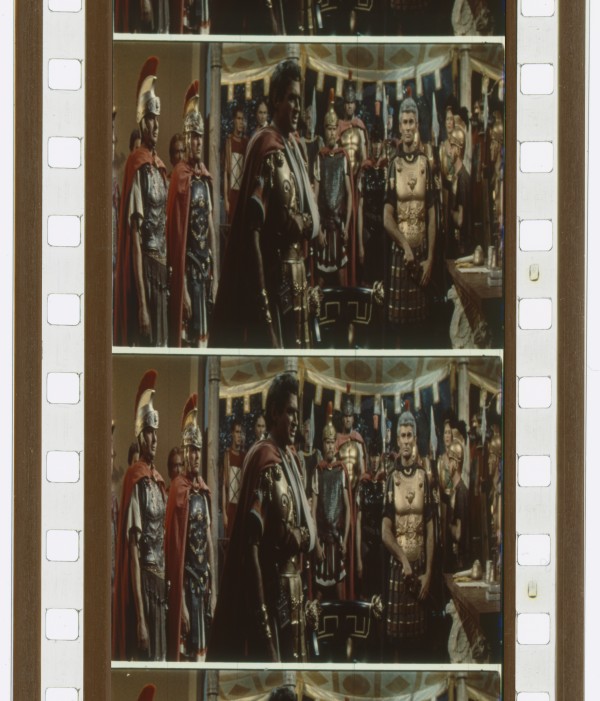

35mm film frame from Sign of the Pagan (Douglas Sirk / Universal, US 1954), showing the compression achieved by the anamorphic CinemaScope lens, four magnetic soundtracks, “Fox-hole” perforations, and color by Technicolor.

Moving Image Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

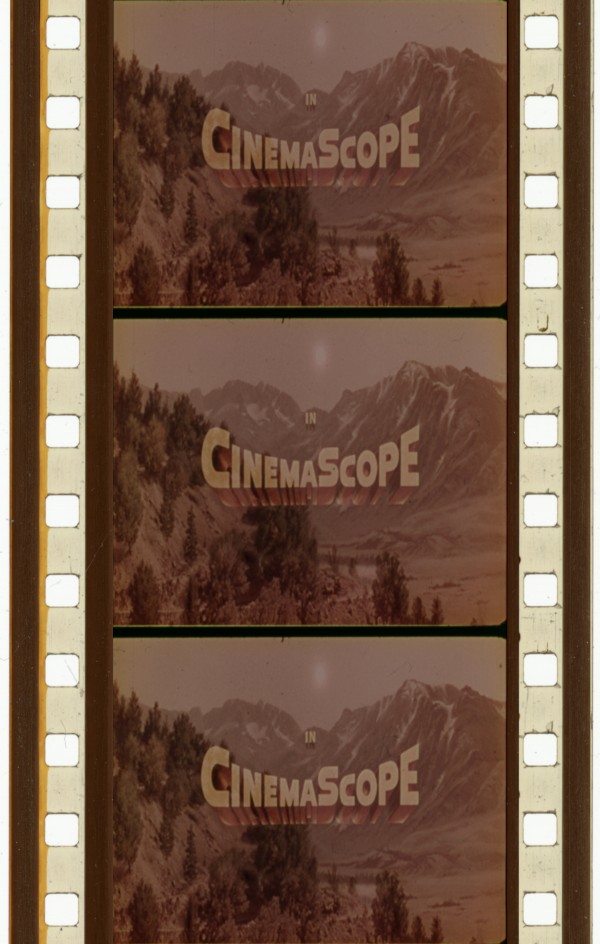

CinemaScope screen credit in Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (Stanley Donen / MGM, US 1954), showing the compression achieved by the anamorphic CinemaScope lens, four magnetic soundtracks, “Fox-hole” perforations, and color (now faded) by Ansco.

Moving Image Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

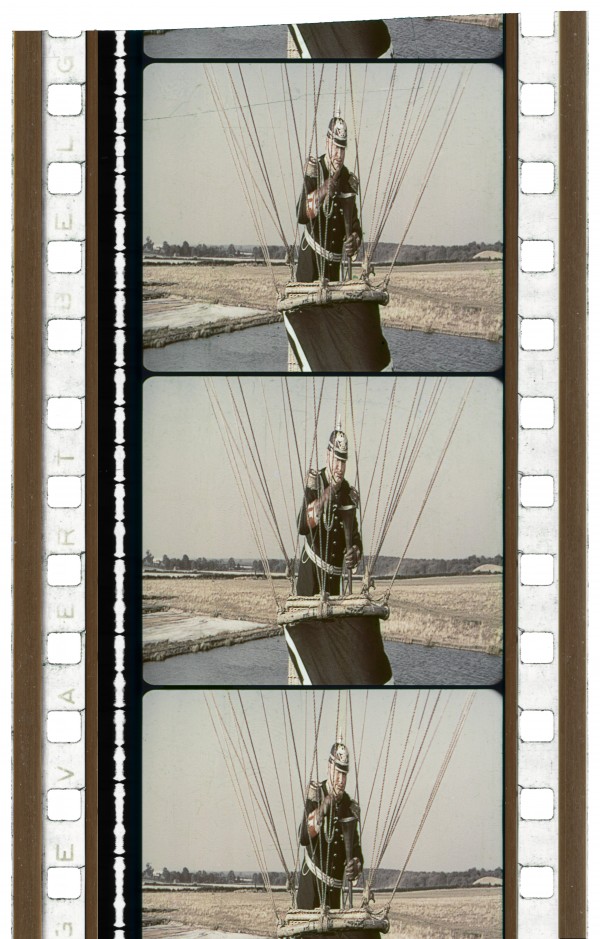

Frames from Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean / Horizon Pictures, UK/US 1957), showing anamorphic compression for a 2.35:1 aspect ratio, optical soundtrack, and color by Eastmancolor (now faded).

Kodak Collection, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.

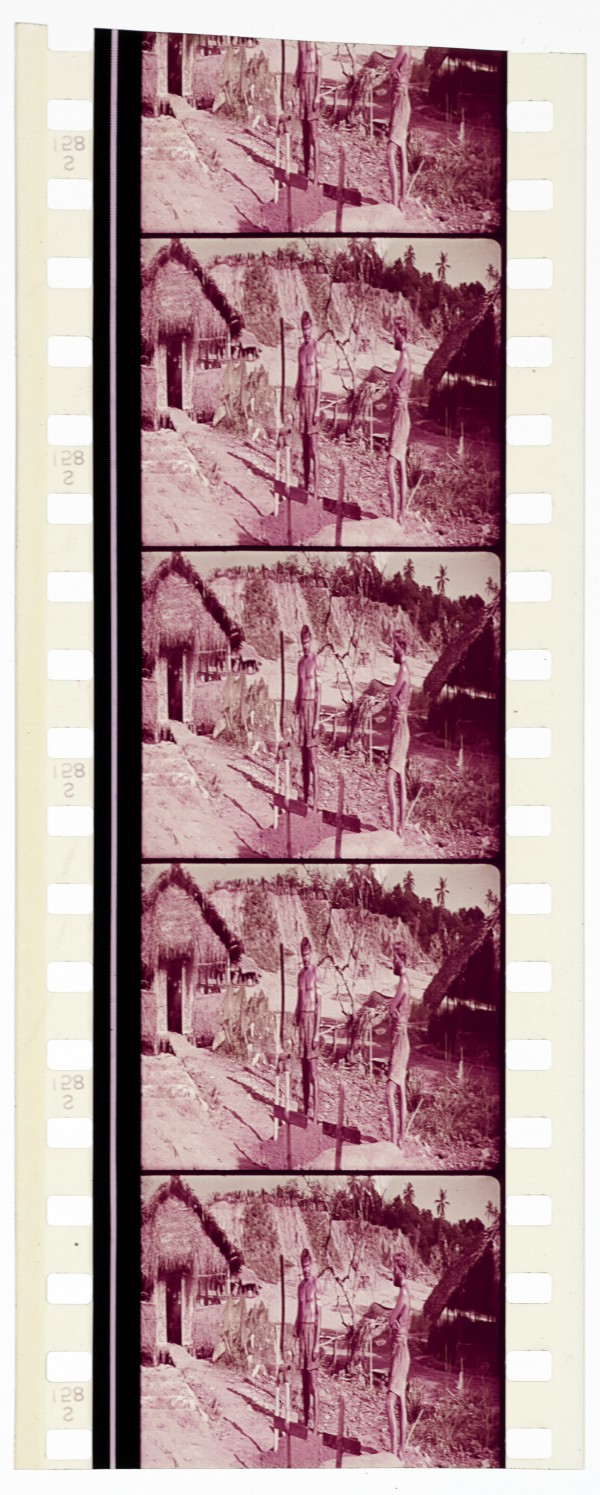

Unidentified film. This 35mm print has four magnetic soundtracks as well as an optical soundtrack (a combination known as “magopt”), with CinemaScope “Fox hole” perforations.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

Identification

For 2.55:1 standard (1953–1956): 23.16mm x 18.16mm (0.912 in x 0.715 in). For 2.35:1 standard (1956–1967): 21.31mm x 18.16mm (0.839 in x 0.715 in).

Demonstrated at 2.66:1 (March–April 1953), originally standardized at 2.55:1 (May 1953), later further reduced to 2.35:1 (1956).

For 2.55:1 standard (1953–1956): CinemaScope (CS), also known as “Fox-hole” perforations. The perforations were reduced in size to allow more room on the print for magnetic soundtracks.

For 2.35:1 standard (1956-1967): Kodak Standard (KS).

Color, B/W.

Edge markings are mostly obscured by the magnetic soundtracks. Later prints with optical soundtracks have clearly visible edge markings.

1

Fox’s initial CinemaScope releases used Eastman Color negative stock processed and printed by Technicolor (giving screen credit to Technicolor). Other studios’ releases used Eastman Color and Ansco Color prints. Although most of Fox’s CinemaScope films were made in color, there was a short run of B/W releases in the mid- to late 1950s.

Twentieth Century-Fox presents a CinemaScope Production (Fox), in CinemaScope (MGM, Warner Bros.), photographed in CinemaScope (Columbia, United Artists, Disney), a CinemaScope production (Universal-International).

Initially: 4-track stereo magnetic soundtrack. In 1954, Fox began releasing each film in three formats: 4-track magnetic, single-track magnetic, and single-track optical. In 1956, Fox announced that all of its CinemaScope releases would have a combined magnetic and optical (“magoptical”) soundtrack. However, by 1958 it was making its films available in optical-only as well as magoptical formats.

1953–1956: 4-track stereo. 1956–?: 4-track stereo and mono. 1958–1967: mono.

4-track: three speakers spaced behind the screen (left-center-right) and a group of speakers placed in the auditorium (either behind or to the side of the seating). Single-track: one speaker placed behind the center of the screen.

For 2.55:1 standard (1953–1956): 23.80mm x 18.67mm (0.937 in x 0.735 in). For 2.35:1 standard (1956–1967): 22.05mm x 18.67mm (0.868 in x 0.735 in).

Color, B/W.

History

An anamorphic widescreen process developed at Twentieth Century-Fox, CinemaScope played a major role in the adoption of widescreen filmmaking and exhibition internationally in the 1950s. The Fox Film Corporation had experimented with widescreen in 1927–30, having developed the 70mm Grandeur system at that time. Grandeur, like the widescreen systems the other studios introduced in that period, failed to catch on. But by the early 1950s the industrial and cultural landscape had changed: the 1948 US Antitrust Paramount Decision had weakened Hollywood’s oligopoly, attendance at movie theaters had dropped precipitously, television was being popularized, and suburbanization as well as an increase in leisure time were driving an interest in more active forms of recreation in the US. The introduction of the widescreen Cinerama system with the premiere of This Is Cinerama (Merian C. Cooper) on September 30, 1952, suggested that widescreen cinema was newly viable and that it might help reverse the fortunes of the ailing film industry. (The reintroduction of stereoscopic 3-D with the release of Arch Oboler’s Bwana Devil in November 1952 incited a similar rash of interest in that technology.) With CinemaScope, Fox succeeded in introducing a widescreen system that could be used by the studios and disseminated widely. Although the other Hollywood studios were experimenting with rival widescreen processes, MGM, United Artists, Disney, Columbia, and Warner Bros. had all agreed to adopt CinemaScope by late 1953, and the process remained in wide use in the US until Panavision’s anamorphic projection and camera lenses were introduced and embraced in the mid- and late 1950s. CinemaScope also circulated internationally, used both for the exhibition of Hollywood films and for local production, though its impact on production across European and Asian film industries derived more heavily from its adaptation into local systems such as the French Dyaliscope, Japanese Tohoscope, and Hong Kong-based Shawscope (Belton, 1992; Huntley, 1993; Belton, Hall & Neale, 2010; Smith, 2017).

Fox’s research and development department had previously dissuaded Fox president Spyros P. Skouras from pursuing Cinerama – and upon the success of Cinerama’s launch, that unit was instructed to “save the situation” (Bragg, 1988: p. 360). Research Department head Earl I. Sponable and his assistant Herbert E. Bragg had both been with Fox since the late 1920s (Sponable having previously worked with Theodore W. Case to develop the sound-on-film system that would be rebranded as Movietone), and they had both worked on the Grandeur system as well as subsequent experiments with 50mm film. In developing the package of technologies that would constitute the CinemaScope system, their aim was to assemble a widescreen process that would replicate the form of “audience participation” attributed to Cinerama while (taking a lesson from their failed experiment with Grandeur) enhancing the prospect of widespread adoption across the industry by making the system more compatible with existing technology and thereby lowering conversion costs. The Fox engineers initially envisioned using 50mm film for this purpose. But they ended up embracing an anamorphic system featuring cylindrical lenses, which made it possible to compress a broad field of view onto standard 35mm film and yielded a wider projected image than 50mm film. By late 1952, Fox had ordered trial anamorphic lenses from Bausch & Lomb and taken out an option on the anamorphic “Hypergonar” lens that French inventor Henri Chrétien had developed in the 1920s. Some of these lenses were still in existence and Fox made initial tests with a Movietone camera and Hypergonar attachment on December 13, 1952. Weeks later, on February 2, 1953, Skouras announced that all future Fox films would be made in CinemaScope – a major gamble for the studio, made in part to prevent a threatened change in management (Bragg, 1988; Belton, 1992; Huntley, 1993; Belton, 2010; Rogers, 2013).

Although Chrétien’s designs were already in the public domain, Fox’s deal with the inventor (finalized on February 10, 1953) enabled the studio to acquire his lenses and, in historian John Belton’s words, “thus gain a temporal advantage over potential rivals, who would have to begin the lengthy process of designing and constructing cylindrical lenses from scratch. The use of existing Hypergonar lenses enabled Fox to commence the actual filming of CinemaScope productions by mid-February 1953.” (Belton, 1992, p. 122) Beginning on March 18, 1953, Fox held well-received industry screenings of demonstration footage, including footage from upcoming CinemaScope releases The Robe (Henry Koster, 1953) and How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco, 1953). Fox’s first CinemaScope release, The Robe debuted at the Roxy Theatre in New York on September 16, 1953. A year later, over 8,000 theatres in North America and over 4,000 theatres in Europe, Asia, Africa, South America, and Australia had been equipped for the system. Despite other studios’ adoption of Panavision’s anamorphic camera lenses as early as 1959, Fox continued branding CinemaScope films into the mid-1960s; its final CinemaScope release was In Like Flint (Gordon Douglas, 1967) (Belton, 1992, “Highlights in the History of CinemaScope”).

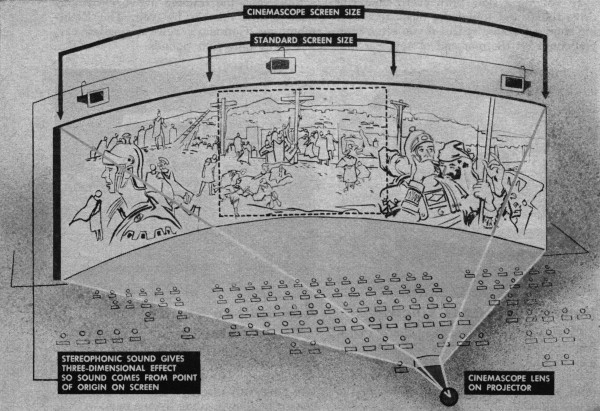

Widely circulated illustration of a CinemaScope installation, emphasizing the single projector, the speaker arrangement for stereophonic sound, and the increased size, scope and curvature of the screen. This arrangement of speakers and screen was reputed to enhance the audience’s experience of “participation”. The pictured film evokes the first CinemaScope release, The Robe (Henry Koster / Twentieth Century Fox, US 1953).

Popular Science, August 1953.

Selected Filmography

Warner Bros. made successive announcements that A Star Is Born would be made in a number of rival formats before finally shooting and releasing it in CinemaScope.

Warner Bros. made successive announcements that A Star Is Born would be made in a number of rival formats before finally shooting and releasing it in CinemaScope.

James Dean’s breakthrough film, which – together with his subsequent role in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray / Warner Bros., US 1955) – made CinemaScope a key component of his image as a star.

James Dean’s breakthrough film, which – together with his subsequent role in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray / Warner Bros., US 1955) – made CinemaScope a key component of his image as a star.

The final film by French auteur Max Ophüls – a lavish production that became a notorious flop at the time of its release, only to be hailed by Andrew Sarris as “the greatest film of all time” – Lola Montès uses CinemaScope both to revel in and to critique spectacle.

The final film by French auteur Max Ophüls – a lavish production that became a notorious flop at the time of its release, only to be hailed by Andrew Sarris as “the greatest film of all time” – Lola Montès uses CinemaScope both to revel in and to critique spectacle.

Technology

The CinemaScope system entailed a package of technologies that promised to invite “audience participation” by making the cinematic experience more immersive. The anamorphic lens provided by Henri Chrétien and subsequently adapted by Bausch & Lomb made it possible to achieve a wider aspect ratio using a single strip of 35mm film. Chrétien’s lens had a horizontal compression factor of about 2:1. Mounted onto a standard film camera, the anamorphic taking attachment made it possible to squeeze an image with an aspect ratio of 2.66:1 onto standard 35mm film (on a full-aperture frame without a soundtrack). Mounted onto a standard projector, a comparable lens would then un-squeeze the image during exhibition, resulting in a wide-view. The spring 1953 CinemaScope demonstration screenings used double-system projection, meaning that the image and soundtracks were run separately, and the footage was shown with a 2.66:1 aspect ratio. However, Fox’s decision to integrate the soundtrack onto the filmstrip for its CinemaScope releases meant that the usable image area needed to be reduced slightly. The CinemaScope aspect ratio was thus initially standardized at 2.55:1. The decision in 1956, to incorporate both magnetic and optical soundtracks onto CinemaScope filmstrips resulted in a further reduction of the aspect ratio to 2.35:1. The Chrétien lenses used on the first CinemaScope productions had certain flaws, including making it difficult to achieve sharp focus and producing distortion (thus causing what was known as the “anamorphic mumps”). Working throughout the second half of 1953 to adapt these lenses and address such issues, Bausch & Lomb had, by January 1954, produced a significantly improved lens to replace Chrétien’s (Benford, 1954; Belton 1992; Huntley, 1993).

Although the anamorphic lens was perhaps the most crucial ingredient in the CinemaScope formula, it worked in conjunction with sound, film, and screen technologies. Like Cinerama, CinemaScope offered multi-track surround sound, in this case with a four-track magnetic format. Fox presented magnetic sound as offering better performance, easier and more economic maintenance and smaller track widths than optical sound. The first three of the four soundtracks were keyed to different areas on the image: left, center, and right. In production, it was advised that three microphones be placed in or above the set (though stereo post-dubbing was also used). In exhibition, three speakers were spaced behind the screen, making it possible for sound to appear to move alongside its source. The fourth track was offered as a “control signal track” and/or a sound-effects track for speakers placed next to or behind the auditorium seating area. In conjunction with the use of four-track magnetic sound, Fox also redesigned the perforations on the filmstrip. Taking advantage of the new cellulose triacetate film stock that had been in use since the late 1940s, which significantly cut down on the shrinkage that had afflicted older nitrate stock, the Fox engineers designed smaller perforations of 0.073 in x 0.078 in (1.85mm x 1.98mm) (subsequently dubbed “Fox-holes”). This new perforation design, paired with the decision to place the magnetic soundtracks on each side of the perforations, increased the usable image area on the filmstrip by 32 per cent – an increase that helped achieve the resolution necessary for projection onto the larger screens that were an integral component of widescreen exhibition. (Whereas pre-1953 screens averaged 18–20 ft (5.5–6m) wide, the first Cinerama and CinemaScope premieres featured 64- and 65-ft-wide (19.5-19.8m) screens respectively.) Finally, the CinemaScope package included screens that would supply the level of brightness necessary for projection at such a scale. Fox’s “Miracle Mirror” screen was embossed with “many tiny concave mirror-like elements” and when formed into a shallow curve as instructed, directionally “reflected the light into the useful theater area, rather than allowing it to scatter at random throughout the theater”, thereby purportedly doubling the image brightness of previous screens (Benford, 1954, pp. 67, 64). Fox initially required that exhibitors adopt the new sound system and screen (or a comparably reflective screen such as the Magniglow Astrolite) in order to show films in CinemaScope. However, in December 1953 it began exempting small theater owners from the screen requirement, and in mid-1954 it also relented on the sound requirement, announcing that it would release its films with monaural optical and one-track magnetic soundtracks in addition to four-track magnetic soundtracks. In 1956 it proclaimed that it would release all of its films beginning with Bus Stop (Joshua Logan, 1956) in a combined magnetic and optical (or “magoptical”) format, which resulted in the further reduction in aspect ratio (and coincided, as well, with its abandonment of “Fox-hole” perforations). By 1958, however, Fox was making its films available in optical-only as well as magoptical formats (Clarke, n.d.; Benford, 1954; Sponable, Bragg & Grignon, 1954; Belton, 1992; Belton, 2004; Rogers, 2013).

This advertisement for Bausch & Lomb projection lenses exemplifies a pervasive tendency to promote CinemaScope in relation to another of Twentieth Century-Fox’s biggest stars, Marilyn Monroe. Motion Picture Herald, August 6, 1955.

Motion Picture Herald, August 6, 1955.

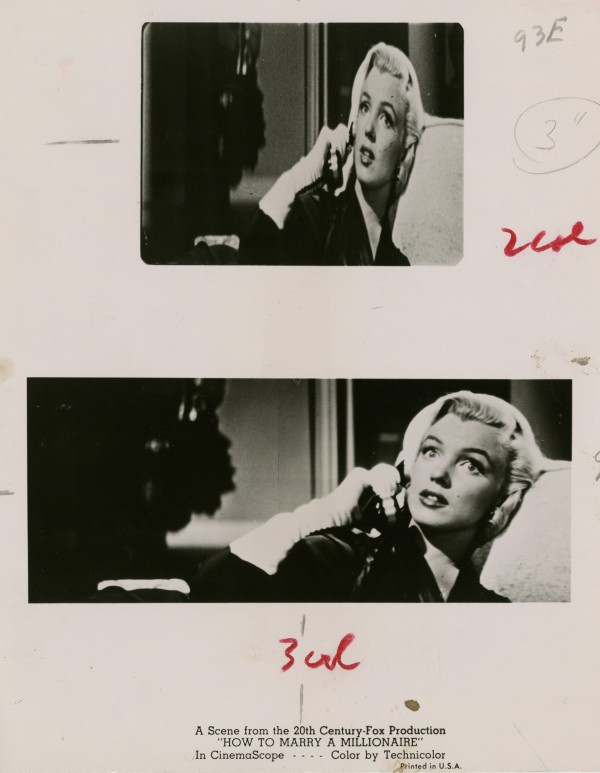

Twentieth Century-Fox used these stills of Marilyn Monroe in How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco / Twentieth Century-Fox, US 1953) to illustrate how CinemaScope lenses compressed the image during photography and then uncompressed it in projection.

Stills, Posters and Paper Collections, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

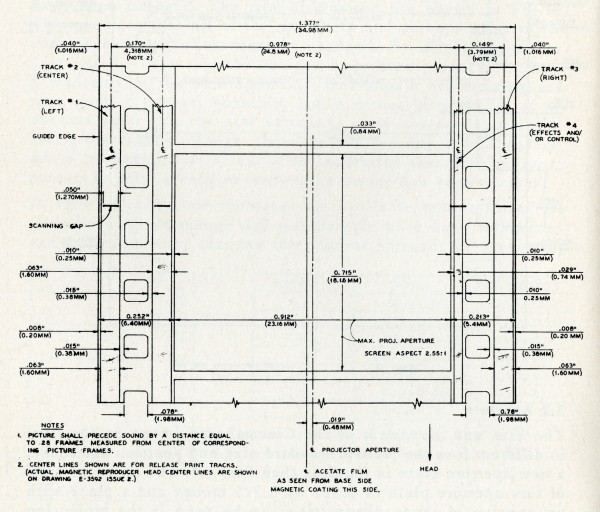

Illustration of Fox’s redesign of the 35mm filmstrip for the first CinemaScope release prints, showing the size and placement of the four magnetic soundtracks as well as the increased frame area afforded by the smaller “Fox-hole” perforations.

CinemaScope Information for the Theatre: 8, c. 1953. Stills, Posters and Paper Collections, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

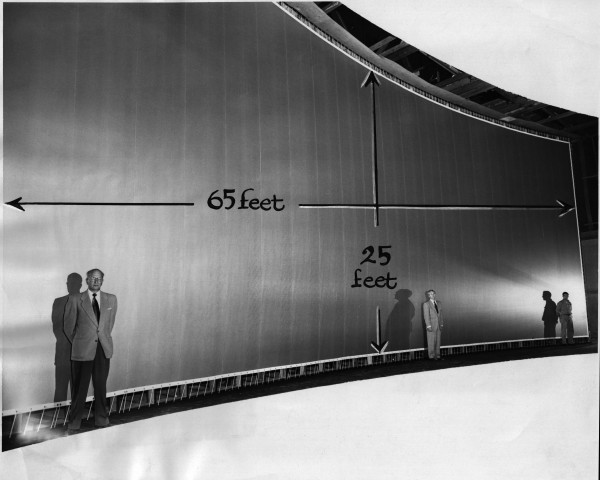

Publicity photograph showing the CinemaScope screen at the time of the spring 1953 demonstration screenings. The dimensions added here reflect the size of some of the first CinemaScope screens.

Author’s collection.

References

Anon. (1953). “CinemaScope – What It Is; How It Works”, American Cinematographer (March): pp. 112–113, 131–134.

Belton, John (2015). “The Commodification of Romanticism: Lola Montès”. Camera Obscura, 30:3: pp. 1–25.

Belton, John (2004). “The Curved Screen”. Film History, 16:3: pp. 277–285.

Belton, John (2010). “Fox and 50mm Film” In Belton, John, Sheldon Hall & Steve Neale (eds) Widescreen Worldwide.

Belton, John (1992). Widescreen Cinema. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Belton, John, Sheldon Hall & Steve Neale (eds) (2010). Widescreen Worldwide. New Barnet, UK: John Libbey Publishing.

Benford, James R. (1954). “The CinemaScope Optical System”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, 62 (January): pp. 64–70.

Bragg, Herbert E. (1988). “The Development of CinemaScope”. Film History, 2: pp, 359–371.

Clarke, Charles G. (n.d.). “CinemaScope Techniques.” Box 106, “Publicity – Addresses and Papers” folder, Earl I. Sponable Collection, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY, United States.

“Highlights in the History of CinemaScope” (n.d.). “CinemaScope: clippings, 1950–1969” folder, Clippings Files, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center, NY, United States.

Huntley, Stephen (1993). “Sponable’s CinemaScope: An Intimate Chronology of the Invention of the CinemaScope Optical System”. Film History, 5: 3 (September): pp. 298–320.

Rogers, Ariel. 2013. Cinematic Appeals: The Experience of New Movie Technologies. New York: Columbia University Press.

Smith, Douglas. 2017. “‘Up to Our Eyes in It’: Theory and Practice of Widescreen in the French New Wave”. Studies in French Cinema, 17:2: pp. 113–128.

SMPTE (1959). “Progress Committee Report for 1958”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, 68: 5 (May): pp. 277–329.

Sponable, E. I., H. E. Bragg & L. D. Grignon (1954). “Design Considerations of CinemaScope Film”. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, 63 (July): pp. 1–4.

Sponable, Earl I. (1954). “Brief Summary of CinemaScope for SMPTE Progress Report”. Box 22, “S.M.P.E. – CinemaScope, 1953-–1955” folder, Earl I. Sponable Collection, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY, United States.

Sponable, Earl I. (1955). “Wide-Screen Motion Pictures”. Box 24, “S.M.P.E. – Wide Screen” folder, Earl I. Sponable Collection, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, NY, United States.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Ariel Rogers is an associate professor in the Department of Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University. Her research and teaching address the history and theory of cinema and related media, with a focus on movie technologies, new media, and spectatorship. She is the author of Cinematic Appeals: The Experience of New Movie Technologies (2013) and On the Screen: Displaying the Moving Image, 1926-1942 (2019) as well as essays on topics such as widescreen cinema, digital cinema, special effects, screen technologies, and virtual reality.

The author gratefully acknowledges James Layton and Crystal Kui for their help with research and images, and thanks Film Atlas’s anonymous reviewers for their productive feedback.

Rogers, Ariel (2024). “CinemaScope”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.