A silver retention process developed in the 1990s by Consolidated Film Industries that offered high-contrast prints with muted colors.

Film Explorer

A 35mm Silver Tint print of Kansas City (1996) with Dolby SR-D soundtracks. This print is in the personal collection of director Robert Altman at the UCLA Film & Television Archive. It is likely a test print and not a final release print.

UCLA Film & Television Archive, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

Identification

Varied

The CFI Silver-Tint process was only applied to film prints. Instead of removing silver particles in the color dye layers, as in standard processing, prints with CFI Silver-Tint retained a high proportion of the original silver content in the emulsion, offering higher contrast with muted colors, compared to standard prints.

1

High-contrast and muted colors compared to standard prints.

None

Varied

Standard color negative. Eastman EXR 200T 5287 was used on Kansas City (1996).

History

During the 1980s through 1990s, many cinematographers and directors of photography requested that film laboratories provide theatrical-feature release prints with substantially higher contrast and deeper blacks than the prevailing system of color negative and positive printing in use. This look simulated leaving a B/W image superimposed over a color image, and was a continuation of the bleach bypass technique, first used in Japan in the 1960s. Many labs developed proprietary techniques to accomplish this, including Technicolor’s ENR, Deluxe’s Color Contrast Enhancement, and LTC’s Noir en couleur.

Consolidated Film Industries (CFI) in Hollywood responded to this request in the early 1980s with its Silver-Tint process. Richard Smith, Technical Director at CFI and former Eastman Kodak Marketing Education Specialist for Motion Pictures, coordinated this effort with the laboratory’s clients, offering options to achieve various degrees of enhanced blacks in the prints. In simple terms, this system involved allowing some silver retention in the film to create greater density (contrast) in the print – this could be controlled to different levels of intensity. CFI offered both an Enhanced Silver-Tint (where 100% of the silver remained in the print) and a Standard Silver-Tint (where only a portion of the original silver content remained).

CFI first utilized Enhanced Silver-Tint for the 1996 Robert Altman film Kansas City, which was shot by Oliver Stapleton. “This process produces a very harsh, high-contrast, hard look,” Smith wrote. “The contrast of the print film increases dramatically and it significantly desaturates colors.” Robert Altman wanted a harsh look for Kansas City. He wanted bland, muted fleshtones and heightened contrast, so he elected to use the Enhanced Silver-Tint on approximately 50 of the film’s show prints. CFI incorporated Standard Silver-Tint on such films as She’s So Lovely (1997, directed by Nick Cassavetes; photographed by Thierry Arbogast) and Joyride (1997, directed by Quinton Peeples; photographed by Stephen Douglas Smith), as well as on the Brazilian feature Un embruyo (1998, directed by Carlos Carrera; photographed by Marcello Durst). For She’s So Lovely, Arbogast wanted CFI to emulate the NEC (Noir en couleur) process offered in France by LTC. Again, from Richard Smith: “For a period of time, we tried experimenting with flashing and special developing on the interpositive to achieve similar results, but ultimately, we released the film with Standard Silver-Tint prints.” (Smith, 2023)

CFI phased-out the Silver-Tint process around 1998, as customer demand for film laboratory processing worldwide drastically diminished as a result of increasing use of digital intermediates and digital release formats, which allowed alternative methods of achieving similar Silver-Tint effects.

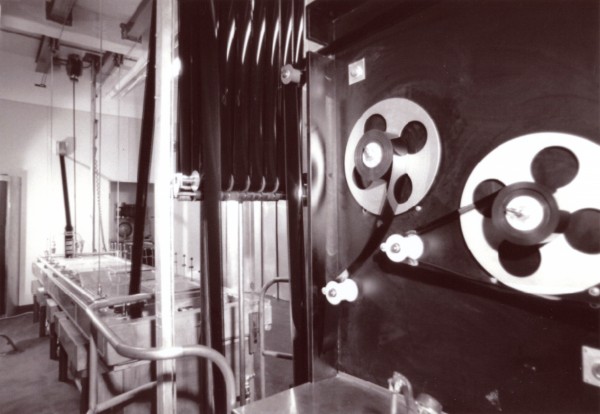

Motion picture print developing machine utilizing 'Silver-Tint' processing in operation at CFI during the 1990s.

Courtesy of Ron Little.

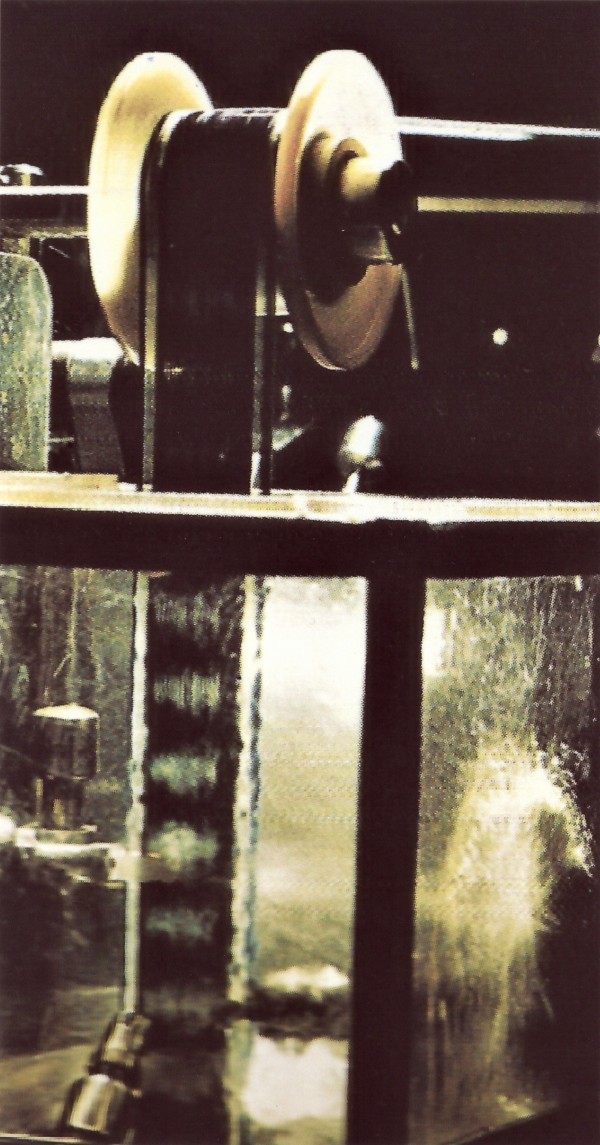

CFI cinetechnician rethreading film in racks containing bleach solution, converting the normal process to the “Silver-Tint” process.

Print film in process – crossing over to skip the bleach bath, achieving the Silver-Tint effect.

Selected Filmography

Standard Silver-Tint.

Standard Silver-Tint.

Standard Silver-Tint.

Standard Silver-Tint.

Enhanced Silver-Tint.

Enhanced Silver-Tint.

Standard Silver-Tint.

Standard Silver-Tint.

Technology

Light-sensitive silver halide crystals are built into the film emulsion during manufacturing to capture light images on film. During processing, the silver halides are converted into metallic silver and then the color couplers in the film react with the oxidation products of the developer to form a dye. The silver is removed from the film during the fixing and bleaching stages of photographic processing in the film laboratory. Once the silver has achieved its purpose, of capturing the visible light during exposure, it becomes a redundant by-product and is subsequently removed. If some of the silver is allowed to remain in the final print, it provides enhanced blacks and higher contrast.

Richard Smith explained: “Both CFI and Fotokem have what you would call an ‘alternative ENR process.’ Because of the constraints of our existing processing tank setup, we are unable to put a true ENR tank inline. We would do that if we had the tank availability, but [as it stands] we would have to reconfigure the entire processor. In normal processing, the film travels through the color developer, stop, first fix, bleach, soundtrack application, wash, second fix, wash, stabilizer and then to the dry-box. In an ENR-type re-silvering process, the B/W developer is introduced after the sound application [or after the bleach] and before the second fixing bath.”

“To differentiate between the two, with the Enhanced [Silver Tint] process, we leave 100 per cent of the silver in the print, resulting in an infra-red reading near 240. But with Standard Silver-Tint, we can remove a portion of the silver, yielding an infra-red value between 165 and 175. Standard Silver-Tint has higher contrast, blacker blacks and desaturated colors compared to a normal print, but not to the same degree as the Enhanced Silver Tint.” (Smith, 2023) The final decision to use either the Enhanced process or the Standard Silver-Tint process was ultimately made by the CFI client.

Close coordination between the laboratory and the production companies’ representatives was required to achieve the preferred degree of this “Silver Tint”. In some cases, tests prints were made, to satisfy the client. In performing this process, a technique referred to as “bleach bypass” was employed, which involved skipping the bleach bath, either completely or partially, by rethreading film in the racks within the film developing machine to provide less (or, no) time within the bleaching section of the process. CFI always strongly recommended that their clients only utilize this modified process for the final release prints, rather than applying it to the original camera negatives, Interpositives (IP), or Duplicate Negatives (DN). Although the bleach-bypassed original negative, IP or DN can be reprocessed to eliminate the skip-bleach effect, this does involve redeveloping the film through the entire process a second time. This redevelopment is always a potentially dangerous operation posing the possibility of damage to the original camera negative, IP or DN elements and has always required the customer’s prior approval.

References

Little, Ron (2006–2023). “The CFI Story: A History of Innovation in Hollywood Motion Picture Film Technology”. Unpublished manuscript.

Probst, Christopher (1998). “Soup Du Jour”. American Cinematographer, 79:11 (November): p. 82.

Rudolph, Eric (1996). “Jazzed Up”. American Cinematographer, 77:9 (September): pp. 34–38, 40, 42.

Smith, Richard (2023). Email correspondence with Ron Little, December 14, 2022–April 26, 2023.

Patents

N/A

Compare

Related entries

Author

Ron Little was the Assistant Plant Engineer & Environmental Health & Safety Officer at Consolidated Film Industries (CFI) from 1971–2003, and was a consultant to Technicolor on cost reduction for their worldwide film laboratories from 2002–2005. Little is author of the forthcoming book The CFI Story: A History of Innovation in Hollywood Motion Picture Film Technology.

Richard Smit

Little, Ron (2024). “CFI Silver-Tint”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.