An amateur camera-projector system that featured 5 in-wide bands of cellulose diacetate film, with spirals of up to 1,664 frames.

Film Explorer

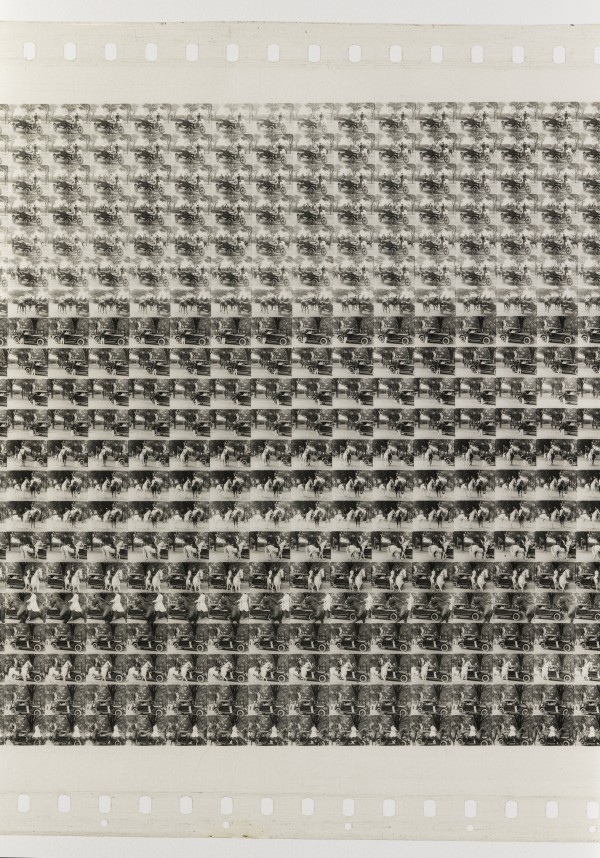

[Home Movie - Orth - Freuler Family with Horses and Car] (c. 1920). Vitalux prints were loops of film 127mm wide that ran horizontally through the projector. Each print contained over 1,000 tiny frames in a continuous row that spiraled around the band of film.

Vitalux Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

Identification

B/W

Small circular holes above every third perforation on the top/tail edge of the loop. Prints of home movies shot with the Vitalux camera feature a black circle between each perforation on the opposite bottom/head edge. This black circle does not appear on prints of Vitalux-distributed films.

(recommended)

1

Some Vitalux prints are tinted. Extant tints include blue, green and yellow.

Vitalux

Silent

6.0mm x 4.5mm (0.236 in x 0.177 in).

B/W, orthochromatic.

Small circular holes above every third perforation on the top/tail edge of the loop.

History

Vitalux was a unique amateur film system that utilized wide strips of cellulose diacetate film, each spliced into a loop which could support a spiral of over 1,600 frames. Introduced in the early 1920s at a time of considerable experimentation and competition within the amateur film market, Vitalux was sold as an affordable alternative to other formats. Unfortunately, its limitations, coupled with the release of Kodak’s 16mm Cine-Kodak system, doomed the company to dissolution by late 1927 (Kattelle, 2000: pp. 65–68).

The seeds of Vitalux were sown in 1914, when German engineer Herman Schlicker filed a patent for a ‘kinetograph’ (Schlicker, 1918). Schlicker had worked in the technical and mechanical departments of several German motion-picture production companies, before traveling to the United States in 1909 (Mahoney, 1913: p 18). His patent attracted the attention of John Freuler, a Wisconsin-born businessman who invested in numerous film-related enterprises including theaters, production companies and film exchanges – the two quickly formed a partnership, with Freuler acting as president (Bruce, 1922: pp. 170–173; Kattelle, 2000: pp. 65–66).

The company was first listed, in a 1917 Milwaukee directory, as Vitalux Products Company, but by 1921 the organization had been renamed the Vitalux Cinema Company. The main thrust for the format came in the fall of 1922 through the spring of 1923, when advertisements appeared initially in Milwaukee newspapers and then in national trade publications, such as Motion Picture News. Vitalux advertising focused on the simplicity and affordability of the format: projector and camera were priced at US$125 and US$175 respectively; negative and positive films were sold at 75 cents each; development cost 25 cents total (Anon., 1922; McKay, 1924: p. 23). In addition to shooting and projecting your own home movies, the company also offered a small library of films for purchase, at $1.25 each: such as documentaries on ice fishing and shipyards; views of Hawaii and Mt. Rainier; and Al Christie comedy shorts (Kesselman O’Driscoll Co., 1922).

However, despite its novelty and affordability, there were obvious downsides to the Vitalux system. For one, editing of any kind was impossible as the loop design prevented it. There was also a length issue: the advertised 1,664 frames per film amounted to a meager two minutes of projection time. Consequently, many of the shorts available from Vitalux were likely edited down and still had to be split into two, or even three, loops. Compounding these issues was the historic unveiling of Kodak’s 16mm Cine-Kodak system in January 1923, right in the midst of the Vitalux advertising push (McKay, 1924: pp. 20–23).

The company pivoted in a number of ways over the next couple years. In 1925, Freuler and Schlicker rebranded Vitalux as the Automatic Movie Display Corporation and began marketing to exhibitors, rather than consumers. They leased Vitalux projectors, in custom display cabinets, to present continuously running still and moving-image promotional material in the lobbies of movie theaters. Freuler claimed that distribution stations for this new venture were being opened in all principal cities east of Chicago and that he expected to place in service no less than 2,000 projectors in 1927 – there is no evidence that either of these claims came to pass (Anon., 1927). Around this time, the Automatic Movie Display Corporation started to advertise laboratory and vault storage space in trade papers, and began distributing their shorts, and other films, as 16mm prints, partnering with Willoughby’s camera store in New York City (Motion Picture News, 1926: p. 1512; Amateur Movie Makers, 1928: p. 147). Ultimately, despite these maneuvers, the company was formally dissolved in August of 1927 – just ten years after that initial Milwaukee directory listing, and only five years after the system was first commercially available (Kattelle, 2000: p. 68).

Home movie featuring Vitalux president John Freuler attending his daughter’s wedding. Because the frames are arranged in a long spiral, down the length of the loop, the images align on a slight incline.

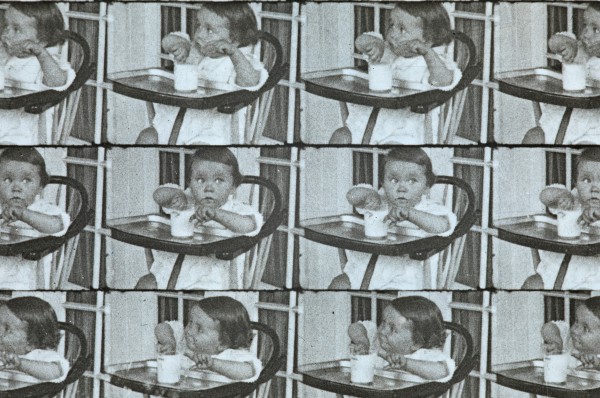

Home movie of Vitalux president John Freuler’s grandchild. The George Eastman Museum’s Vitalux Collection was donated by a relative of John Freuler and consists of 80 loops – half of the films are home movies of the Freuler family, and the other half are produced shorts. It is currently the largest collection of Vitalux films known to exist.

Early Vitalux trade advertisement. Vitalux ads stressed the system’s affordability and ease of use.

Vitalux Cinema Company. Advertisement. Wollensak World, 3:5 (May, 1923).

Selected Filmography

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

An excerpt from this Henry Murdock comedy released by Vitalux under the title The Honey Mooners.

An excerpt from this Henry Murdock comedy released by Vitalux under the title The Honey Mooners.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

An excerpt from this Bobby Vernon comedy released by Vitalux under the title Nightie Night.

An excerpt from this Bobby Vernon comedy released by Vitalux under the title Nightie Night.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

An excerpt from this Henry Murdock comedy released by Vitalux under the title Willie’s Wallet.

An excerpt from this Henry Murdock comedy released by Vitalux under the title Willie’s Wallet.

An excerpt from this Dorothy Devore comedy released by Vitalux under the title Phoebe’s Fellows.

An excerpt from this Dorothy Devore comedy released by Vitalux under the title Phoebe’s Fellows.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

An excerpt from this Bobby Vernon comedy released by Vitalux under the title All Aboard!

An excerpt from this Bobby Vernon comedy released by Vitalux under the title All Aboard!

An excerpt from this Doreen Turner comedy released by Vitalux under the title Puppy Love.

An excerpt from this Doreen Turner comedy released by Vitalux under the title Puppy Love.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Documentary footage. Original title unknown.

Technology

Vitalux films were 5-in (127mm) wide, 17.5-in (444.5mm) long strips of non-flammable cellulose diacetate safety film, which were pre-spliced into loops for exposure and projection. The hand-cranked, 11-lb (4.99kg) Vitalux camera measured 8½ in x 11 in X 4¼ in (215.90mm x 279.40mm x 107.95mm), and was operated with an insertable magazine which carried the spliced band of film, and allowed for daylight loading and quick reloading. The film was advanced horizontally in the camera by a double-claw – driven by two scotch-yoke mechanisms – which grabbed the perforations at each end of the loop. Bands of 6mm x 4.5mm (0.236 in x 0.177 in) images were recorded along the film in a spiral from bottom to top. To accomplish this, the camera's lens moved along a vertical axis (Kattelle, 2000: pp. 66–67).

The Vitalux projector was, by necessity, heavier (at 25 lb [11.34kg]) and even more mechanically involved – for it needed to reproduce the motions of the camera, as well as match the vertical movement of the lens with the lamphouse. An additional function allowed the lens to be quickly cranked back to its original position once the film had reached its end. Both the cameras and projectors were manufactured at the Vitalux plant in Milwaukee (Kattelle, 2000: pp. 66–67).

Scant documentation exists on the Vitalux laboratory process, but their early advertising pamphlet suggests that customers could send their films to the Vitalux Laboratories, their local photograph lab, or develop and print the films themselves. For this purpose, Vitalux offered a “negative film stretcher” and “positive developing frame”, as a part of their accessories. Vitalux prints and negatives were sold in tall, light-tight canisters containing 12 bands of film each. Based on existing examples, pre-tinted stocks were available for prints in yellow, blue and green (Anon., 1922).

Vitalux film. Vitalux prints were advertised as containing 1,664 frames, which resulted in approximately two minutes of runtime. Some releases were tinted: extant tints include yellow, blue and green.

Vitalux Collection, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States. Photographed by Elizabeth Chiang.

Vitalux projector.

Technology Department, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY; Photographed by Ira Srole.

References

Anon (1922). Makes Yesterday Today: Vitalux Motion Picture Machines. Milwaukee, WI: Vitalux Cinema Company.

Anon. (1927a). “Automatic Movie Display Corp. – New Motion Picture Industrial Corporation Formed with Capital of 300,000 Shares”. The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, 124:3217 (February 19): p. 1070.

Anon. (1927b). “Capital Increased”. The Film Daily, 39:38 (February 14): pp. 1–4.

Automatic Movie Display Corporation (1927a). Advertisement. Advertising & Selling,June 1927.

Automatic Movie Display Corporation (1927b). Advertisement. Amateur Movie Makers, December 1927.

Bruce, William George (1922). History of Milwaukee City and County, Vol. III. Chicago, IL: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company: pp. 170–173.

Kattelle, Alan (2000). Home Movies: A History of the American Industry, 1897-1979. Nashua, NH: Transition Publishing.

Kesselman-O’Driscoll Co (1922). Advertisement.

Mahoney, The (1913). “Just Gossip”. The Moving Picture News, 7:26 (June 28): p. 18.

McKay, Herbert Couchman (1924). Motion Picture Photography for the Amateur. New York, NY: Faulk Publishing Co., Inc.

Vitalux Cinema Company (1921). Listing. Milwaukee City Directory, 1921.

Vitalux Cinema Company (1923). Advertisement. The Milwaukee Journal, February 9, 1923.

Vitalux Cinema Company (1923). Advertisement. Motion Picture News, April 21, 1923.

Vitalux Laboratories. Advertisement (1926). Motion Picture News, October 16, 1926.

Vitalux Products Company (1917). Listing. Milwaukee City Directory.

Willoughby’s (1928). Advertisement. Amateur Movie Makers, March 6, 1928.

Patents

Schlicker, H. C. Kinetograph. US patent US1256931A, filed April 11, 1914, and issued February 19, 1918. https://patents.google.com/patent/US1256931A

Schlicker, H. C. Moving picture projector. US patent US1504722A, filed October 17, 1919, and issued August 12, 1924. https://patents.google.com/patent/US1504722A

Compare

Related entries

Author

Kirk McDowell is a film archivist interested in short-lived and experimental amateur film systems. As Assistant Collection Manager in the Moving Image Department of the George Eastman Museum, he helps care for over 100,000 reels in the archive’s collection, facilitates donations, handles nitrate and safety shipments and teaches small-gauge film inspection. He is a 2018 graduate of the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation and has previously held positions at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Library of Congress, and the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.

Todd Gustavson, Glenn Galbraith, Peter Bagrov, Deborah Stoiber, Steve Massa.

McDowell, Kirk (2024). “Vitalux”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.