A small-gauge film format introduced by Kodak in 1932 for the amateur/home-movie market.

Film Explorer

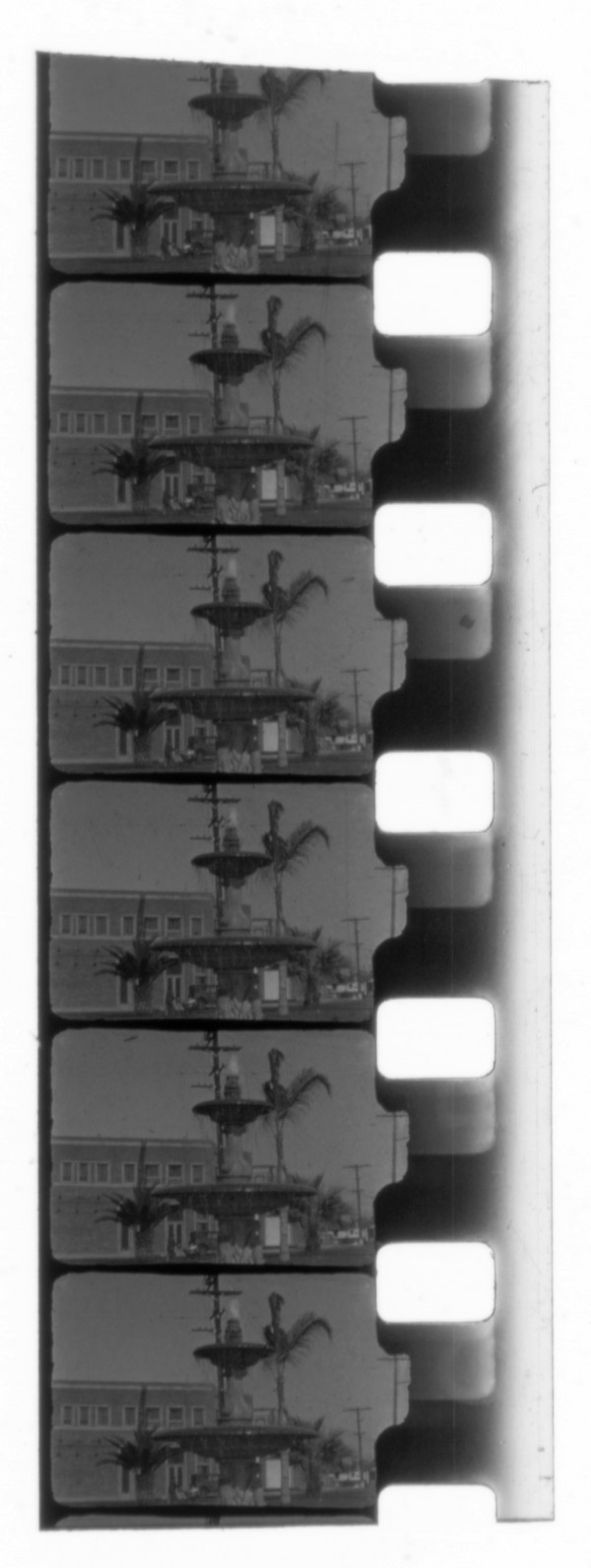

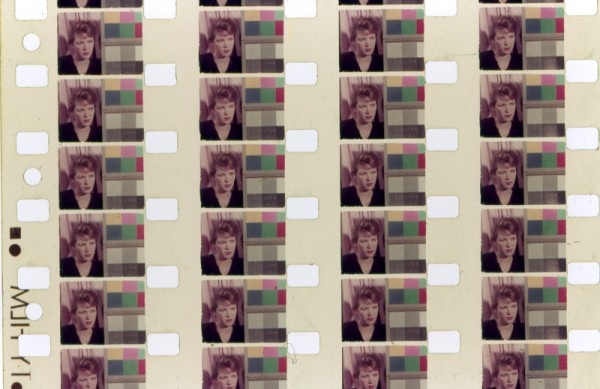

Standard (or double) 8mm starts out as a 16mm-wide film, before being slit into two strips after processing – this image shows a processed film that has not been slit. Notice that the images run in opposite directions on the two halves of the unslit film.

Film Frame Collection (P-074), Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

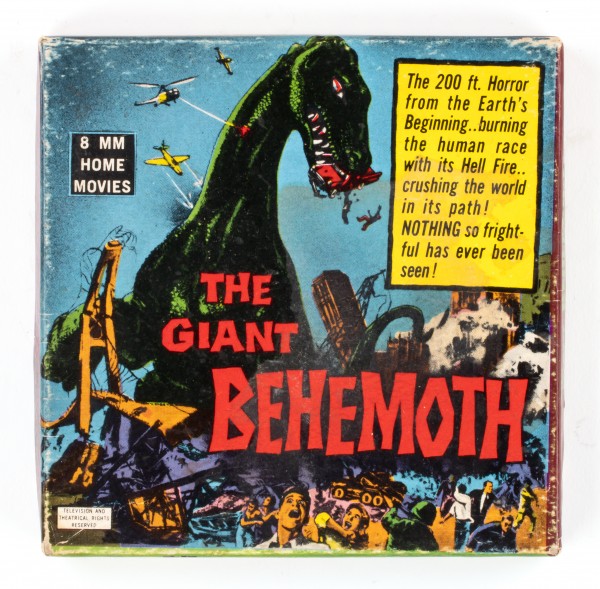

This image shows an 8mm camera reversal original after being processed and slit. Between the perforations is a small indent that can help identify the camera used for filming – in this case a Cine Kodak Model 20 F/3.5. The unexposed edges of the film are black, indicating that this is a reversal film.

Film Frame Collection (P-074), Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

An example of unslit 8mm Kodachrome from the mid-1930s. Kodachrome from this period is prone to color fading.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, United States.

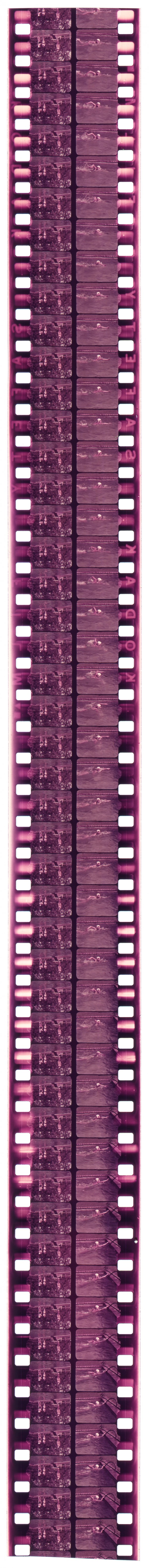

A silent 8mm print of an excerpt from the sound feature Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959), distributed for home projection as The Great Behemoth.

Courtesy of John Wallace, Tangible Media Collection, Ithaca, NY, United States.

Identification

4.37 x 3.28mm (0.172 in x 0.129 in).

Color or B/W.

8mm reduction prints have clear edges and may feature film manufacturing edge markings.

16 fps standard for cameras and projectors. Cameras such as the Bolex H-8 allowed for 8, 16, 24, 32, 48 and 64 fps, while others would allow single-frame advancement for stop-motion animation.

1

The following color reversal film stocks were available in the 8mm format: Kodachrome, Ferraniacolor, Gevacolor, Ilfochrome (selected list).

First introduced as a silent process. Movie-Sound-8 (sound-on-disc) projector, introduced 1947, and Kodascope Sound 8 Projector (magnetic sound recording/playback), introduced 1960, were both non-synchronized sound playback options that were later offered (although magnetic sound projectors from other companies were available earlier – see Kattelle, 2000, p. 234). Magnetic sound was usually achieved by adding a magnetic stripe to the film strip after processing, but it was initially difficult to obtain good-quality sound, due to the slow speed of the film strip’s movement, and the small area available for a magnetic stripe on the film. A small number of 8mm cameras with magnetic sound recording capability were eventually marketed, such as the Fairchild Cinephonic 8 (1960), but these met with limited success. The standard adopted, for 8mm film with a magnetic sound stripe, located the sound 56 frames in advance of the corresponding image. Optical soundtracks were used on some 8mm prints, but these were uncommon – perhaps due to the high costs involved. Beginning in the 1960s, some companies introduced 8mm projectors capable of playing both magnetic and optical soundtracks, an example being the Toei Motion Picture Co.’s Toei 8 Talkie.

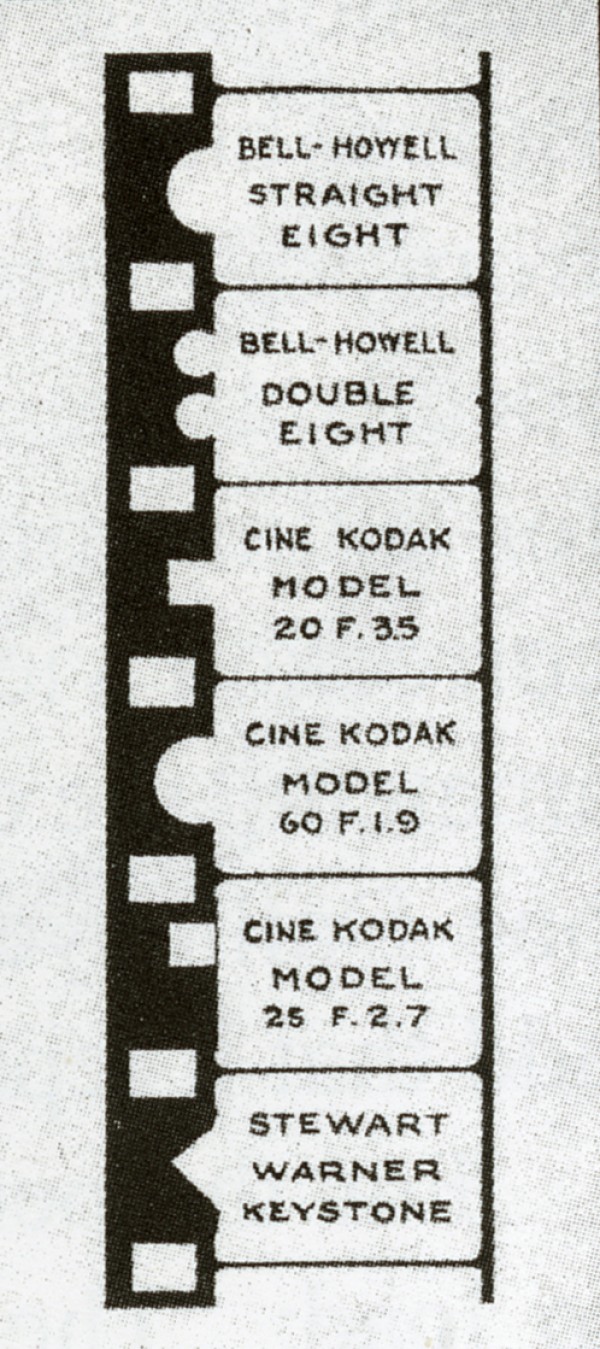

For the 8mm format initially introduced by Kodak, reversal camera film was supplied on 16mm-wide stock with 8mm perforations on both sides of the film (“double perf”). Users would expose one complete row of 8mm images, then flip the roll over and run the film back through the camera, shooting to expose the other side. After both sides of the film were exposed, the roll was processed and slit into 8mm width by the lab. Some companies, such as Bell & Howell, introduced a pre-split, 8mm-wide film (marketed as Straight Eight) which could be exposed without the need to flip the roll midway through.

4.8mm x 3.51mm (0.189 in x 0.138 in) [1941 SMPE standard].

8mm was introduced by Eastman Kodak in 1932 on a fine-grained, panchromatic, supersensitive B/W safety stock. A variety of options were eventually available, including Kodachrome in 1936.

The edge code markings on Kodak 8mm present a unique challenge. Kodak’s Kodachrome 8mm film stock was controlled by the Professional Products division, not the Motion Picture division, and therefore edge printing was not standardized between the various gauges. While 8mm follows the standard symbol set that Kodak’s 16mm and 35mm employed, the symbols for 8mm changed every six months and were repeated every 10 years. Furthermore, symbols used in the US and UK differed. As a result, the standard and widely accessible Kodak edge code chart is of limited use for 8mm films (Layton, 2020). In addition to edge code markings, 8mm reversal stocks feature a characteristic black edge.

History

Since the 1910s, various small-gauge film formats were introduced in an effort to extend filmmaking beyond the professional sphere, and to make film exhibition an option for home entertainment (see Edison Home Kinetoscope, 28mm, 9.5mm 16mm). While the introduction of the 9.5mm and 16mm formats (in 1922 and 1923, respectively) were important steps in the expansion of filmmaking and exhibition outside of professional contexts, their equipment and film stocks remained expensive, with their use generally limited to the upper-middle and upper social classes. It was not until the arrival of the 8mm format that filmmaking would come within the financial reach of a much broader segment of the population in industrialized nations. With the arrival of 8mm film, home movies became ubiquitous and the format dominated the realm of non-professional filmmaking for more than three decades – right up to the arrival of Super8 in 1965 (Zimmermann, 1995; Tepperman, 2014).

The 8mm film format was first patented by Fritz Coors Jr. in Germany in June 1930 – the patent was later assigned to Eastman Kodak, who brought the format to market in July 1932. The process was advertised as reducing the cost of amateur filmmaking by more than two-thirds. This was accomplished by registering a smaller image on each half of 16mm film stock – essentially printing four times as many frames on the film strip – and then slitting this strip end to end to produce two 8mm strips that were spliced together. In the camera, one half of a 16mm-wide film roll could be exposed traveling in one direction, and then flipped over at the end of the reel to expose the other half of the frame, running through the camera again. After processing, the 25-ft camera roll would yield 50 ft of 8mm, which was equivalent in number of frames to 100 ft of 16mm. Projected at 16fps, 50 ft of 8mm film gave a duration of approximately four-and-a-half minutes.

When Kodak introduced this format in 1932, it also introduced the Cine-Kodak Eight camera, two Kodascope 8mm projector models and a range of other accessories (screens, editors, titlers, etc.). Due to the smaller image produced, Kodak employed a superfine emulsion film – nonetheless, the intended image size in projection was initially quite small, a maximum of 30 in x 22 in (76.20cm x 55.88cm). The equipment offered was initially simplified, so that Kodak could market the system based on its ease of use. Over time, a greater variety of customizable equipment was marketed. Though some alternatives to 8mm were introduced, the gauge grew in popularity over the 1930s and several companies introduced 8mm equipment, including projectors and cameras, along with splicers, viewers, editors and other accessories (Kattelle, 2000; Zimmermann, 1995). Notably, several companies introduced a pre-split 8mm film stock, known sometimes as Straight Eight (Bell & Howell’s brand, introduced in 1935): the last of these faded from view around 1946 (Kattelle, 2000). The format was initially only available on B/W stock, but 8mm Kodachrome was introduced in 1936, one year after 16mm Kodachrome. Initially a silent film format, starting in the 1940s, sound-on-disc and, later, magnetic sound-on-film projectors were introduced for 8mm.

When the 8mm format was introduced in 1932 it was intended as a lower-cost amateur format that would increase the number of people making films. This was a response both to the relatively high cost of 16mm film and the challenging consumer environment during the Great Depression. The 8mm format was marketed as the perfect format for home movies and family “snapshot” filmers, leaving the 16mm format to advanced amateurs, semi-professional and other non-theatrical filmmakers (Tepperman, 2014: pp. 117–24).

As a consequence of this widespread non-professional use, the majority of films shot in 8mm reflect the image-making practices of everyday life: chronicling birthday parties and holidays; families and friends; domestic spaces; but also community life and travel. Home movies of this kind can depict both social and cultural norms of the period, as well as events and realities of crucial historical significance (see archive.org collection of home movies). As 8mm film became ubiquitous, it provided unofficial records of events that often eluded professional production, such as the recording of US President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 by Abraham Zapruder (the most notable among many 8mm film records of the event). 8mm films also captured lives and events in communities that were marginalized in the cultural record and commercial media, such as the daily lives of African-Americans (South Side Home Movie Project), the experience of Japanese-Americans in US internment camps, and Jewish communities in Polish ghettos before and during World War II. Though 8mm filmmakers are in many cases un-known and un-trained, and the films can reflect unpolished technique (frequently unedited, using hand-held cameras), home movies provide invaluable records of both private and public lives (Zimmermann & Ishizuka, 2008).

8mm film also provided creative opportunities for makers of non-professional and art films. The relatively low cost of filming provided access to artisanal filmmakers and small groups, permitting them greater opportunity for experimentation and expression than was possible with more expensive commercial equipment. Starting in the early 1930s many “advanced amateur” filmmakers adopted 8mm film to make short creative works which circulated among movie clubs and beyond (Tepperman, 2014). The 8mm film format was also adopted by avant-garde and experimental filmmakers (especially in the 1950s and 60s), who employed the format both for low-cost production of personal and challenging works, but also to encourage more intimate presentation of films, in both domestic and community spaces (see Stan Brakhage and George & Mike Kuchar). 8mm film also enabled motion picture production in countries with small, or non-existent film industries – 8mm filmmakers in Latin America and the Middle East, for example, used the format to initiate film production rooted in local and regional cultures. Overall, the 8mm format extended access to filmmaking far beyond professional, and even 16mm filmmaking communities. While 8mm films may encompass fewer well-known directors and acknowledged masterpieces, they were also a site for creative innovation and their historical and cultural significance defined the look and historicity of the middle of the twentieth century.

Beyond its use as a non-professional production format, 8mm was also a significant exhibition format, most commonly for viewing films in the home, but also to present films in any other space a portable projector could travel (Wasson, 2021). While home movies made up a portion of the films viewed on 8mm, professionally-produced films were also reduction-printed and marketed to owners of 8mm projectors. Shortly after the introduction of 8mm, Kodak began to offer Cinegraph Eight films, a continuation of their Kodascope 16mm library service. Other companies quickly entered the 8mm distribution field in the 1930s, with Castle Films and Blackhawk Films prominent among them. Eventually, the widespread use of 8mm projectors and the commercial availability of reduction-printed films on the format meant that it was used for the exhibition of a wide range of non-theatrical film venues and types, including industrial, educational and erotic films (Slide, 1992; Wasson, 2021).

Packaging for Ferrania’s Ferraniacolor reversal film, c. 1950s. Notice on the packaging that it specifies the stock is balanced for daylight, meaning it will render normal looking colors from natural daylight. For indoor filming a tungsten-balanced stock would be recommended, or filters were required to correct color balance.

H. A. V. Bulleid Collection, East Anglian Film Archive, Norwich, United Kingdom.

A typical example of what the packaging for an 8mm reduction-print would look like. Note that unlike the packaging for unexposed camera stock, this packaging lists no information about the film’s characteristics other than that it is 8mm.Courtesy of John Wallace, Tangible Media Collection, Ithaca, NY, United States.

Courtesy of John Wallace, Tangible Media Collection, Ithaca, NY, United States.

Selected Filmography

Part of the “Songs” cycle of experimental films (1964–69).

Part of the “Songs” cycle of experimental films (1964–69).

The voice-over narration of a Turkish poem about Amentü Gemisi (the Amentü Ship), a synthesized musical soundtrack, emulating Turkish classical music, accompanies the film’s calligraphic sequences; generally regarded as one of the earliest film animations in Turkish cinema history.

The voice-over narration of a Turkish poem about Amentü Gemisi (the Amentü Ship), a synthesized musical soundtrack, emulating Turkish classical music, accompanies the film’s calligraphic sequences; generally regarded as one of the earliest film animations in Turkish cinema history.

Campy experimental film.

Campy experimental film.

Documentary that compiles 8mm footage shot by six German soldiers during World War II, along with interviews with the filmmakers about their experiences.

Documentary that compiles 8mm footage shot by six German soldiers during World War II, along with interviews with the filmmakers about their experiences.

Home movie record of New York City Christmas scenes – in the city and at home.

Home movie record of New York City Christmas scenes – in the city and at home.

Home movies on 8mm and accompanying analysis by scholar Chuck Kleinhans. https://www.centerforhomemovies.org/aunt-alices-home-movies/

Home movies on 8mm and accompanying analysis by scholar Chuck Kleinhans. https://www.centerforhomemovies.org/aunt-alices-home-movies/

Documentary about the history of home movies, featuring 8mm footage from the filmmaker’s own family.

Documentary about the history of home movies, featuring 8mm footage from the filmmaker’s own family.

Amateur film documenting life in the Japanese internment camp called Topaz War Relocation Center, located in Millard County, Utah.

Amateur film documenting life in the Japanese internment camp called Topaz War Relocation Center, located in Millard County, Utah.

An award-winning short, amateur fiction film with atmospheric cinematography. https://eafa.org.uk/work/?id=1026474

An award-winning short, amateur fiction film with atmospheric cinematography. https://eafa.org.uk/work/?id=1026474

Technology

The core principle behind 8mm – multiple rows of images on a single strip of film – was not untested by the time Kodak introduced the 8mm format. The genealogy of similar technological innovations can be traced back to short-lived and obscure formats such as Vitalux (1914), Theodore Brown’s Spirograph (1906), and Edison’s Home Kinetoscope (1912), all of which utilized a similar arrangement of projectable images in parallel rows. However, these early multi-image formats – notably the Vitalux, which was both a format for home projection and a proprietary camera for amateur production – had a major drawback when it came to editing. As Fritz Coors Jr. notes in his 8mm patent application, editing was restricted with existing formats as “an undesirable portion of one series could not be removed without removing a possibly desirable portion of the other series appearing on the same length of film” (Fritz Coors Jr., 1933: p. 1). Kodak’s 8mm format solved this issue by utilizing the rows of images only for the in-camera capture before slitting them post-processing. This would solve the editing problem by reorientating the two rows of images into a single row of frames – like a standard film reel – that could then be edited in a conventional manner. Furthermore, by utilizing 16mm-wide film, existing standard processing equipment in laboratories could be used. In proposing a film roll that was designed to be run through a camera twice, exposing half of the reel on each run, before being slit down the center, the design resembled an experimental camera Frederick W. Barnes had demonstrated at Kodak in 1914, which used 35mm film to produce a pair of 17.5mm film strips (Kattelle, 2000).

With the introduction of 8mm film came a series of new cameras and projectors. The initial camera launched by Kodak was known as the Ciné-Kodak Eight Model 20 and came with a fixed-focus f3.5 Anastigmat lens (Ciné-Kodak Salesman, July 1932, p. 2). The two projectors that were available at launch were the Kodascope Model 20 and Model 60, both of which could be purchased for 60Hz AC or, for a slightly higher price, a universal (AC, or DC) model, which would allow the projector to be run off a battery, if needed. Both projectors were essentially the same, but with the Model 60 coming with a carrying case and a few more additional features. Shortly after the initial launch, Kodak introduced the Ciné-Kodak Model 60, a similarly small-sized camera, but with a faster f1.9 lens that could be swapped for a 1.5-in f4.5 telephoto lens (Ciné-Kodak Salesman, Oct 1932, p. 1). In July 1933 Kodak introduced the Ciné-Kodak Model 25, which featured a slightly faster f2.7 lens, something they noted was needed for indoor filming – it was hoped this model would also “lead to many sales of the Kodaflector and Mazda Photoflood lamps” (Ciné-Kodak Salesman, 1933, p. 1). During the 1930s, many companies brought a myriad of 8mm cameras and projectors, with a wide range of features and price points, to the market (See Kattelle, 2000, for an incomplete list of 8mm cameras and projectors).

Beginning in 1940, Kodak introduced a newer and more user-friendly camera, the Ciné-Kodak Magazine 8. Instead of using the standard 25-ft daylight-load spools, the Magazine 8 used a cartridge that was simply inserted into the camera. The benefit of this was that the user no longer needed to fuss with threading the film as well as potentially exposing areas of unexposed film to light. Secondly, the user could now easily change from a B/W stock to a color stock (such as Kodachrome) at any point, without exposing the film roll to ambient light (American Cinematographer, July 1940, p. 316). Alongside the Ciné-Kodak Magazine 8, which featured a removable lens, came a range of new interchangeable lenses, ranging from a 9mm f2.7 fixed-focus wide-angle, to a 76mm f4.5 telephoto. The differing designs of the camera aperture plates in these various 8mm cameras often left distinctive marks on the film between the perforations, which are of value to archivists in determining the camera used in the making of the film.

8mm reduction prints for education, or entertainment, were made by one of two methods: The first, by means of a specially prepared intermediate negative (reduction intermediate) print element and a pre-perforated 35mm positive film strip, which would then be contact printed. The second method employed a continuous optical reduction printer (Happé, 1974: pp. 174–5): a special copy lens using a prism, or additional lenses, could be added to the optical printer in order to print four 8mm strips side-by-side across the 35mm print stock (Cleveland & Pritchard, 2015: pp. 373–4) – a method suited to printing large runs of 8mm prints. This process was also used for smaller runs of prints, employing 16mm as the print stock – allowing for two 8mm prints to be made. The print elements of either process (whether two prints on 16mm, or four on 35mm) were often referred to as multi-rank intermediates.

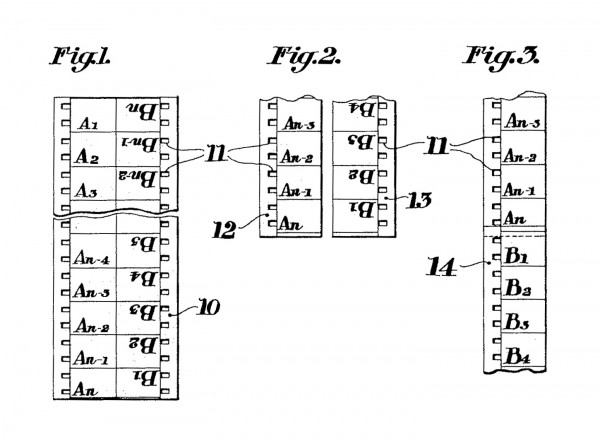

These diagrams are from Fritz Coors Jr.’s original patent and depict the concept of having two separate images side-by-side on a width of film. Figure 1 shows the camera-original film with images (A) orientated upright, while the others (B) would appear upside down, before being slit. Figure 2 shows how the film would be slit after processing and Figure 3 after the two lengths have been spliced together. Note: the perforation pattern on these diagrams does not match that which would eventually be used – 8mm perforations are actually positioned at the frame line.

Coors, Fritz Jr. 1931. Method for Producing Motion Picture Film. US Patent 1,905,442, filed June 2, 1931, and issued April 25, 1933.

This diagram – though not exhaustive – shows the various marks found between the perforations of the camera-original film, which can identify the camera used for filming. This was exposed onto the film by the distinctive shapes of the different camera aperture plates.

Cleveland, David & Brian Pritchard (2015). How Films Were Made and Shown. Manningtree: David Cleveland.

This image shows how 8mm prints were made on a pre-perforated 35mm film strip – in this case four 8mm prints on each 35mm strip. Note that the 8mm perforations are those to the left of the image – the perforations along the far-right side, which feature the words “SAFETY FILM” and traditional edge code markings, would be discarded after slitting. In contrast to camera-original reversal copies with dark edges, the edge of this film (rebate) appears clear.

Brian R. Pritchard

References

American Society of Cinematographers (1940). “Eastman’s 8mm. Camera Makes Marked Advance”. American Cinematographer, 21:7 (July): p. 316.

Cleveland, David and Brian Pritchard. 2015. How Films Were Made and Shown. Manningtree: David Cleveland.

Eastman Kodak Company (1932). “Introducing a New $29.50 Eastman Movie Camera”. Ciné-Kodak Salesman, 2:5 (1932): pp. 1–5.

Happé, L. Bernard (1974). Your Film & The Lab. New York, NY: Hasting House.

Ishizuka, Karen L. & Patricia Rodden Zimmermann (eds) (2008). Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kattelle, Alan D. (2000). Home Movies: A History of the American Industry, 1897–1979. Nashua, NH: Transition Publishing.

Layton, James (2020). “Eastman Kodak”. In Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification, Camille Blot-Wellens (ed.), pp. 255–6. Brussels, Belgium: FIAF.

Lewis, Robert E. (1947). “A Survey, 8mm Problems”. Journal of the SMPTE. ,49:5 (Nov.): pp. 439–452.

Slide, Anthony (1992). Before Video: A History of the Non-theatrical Film. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Society of Motion Picture Engineers (1933). “Report on the Progress Committee: Amateur Cinematography”. Journal of the SMPTE, 20:6 (June): pp. 472–476.

Society of Motion Picture Engineers (1941). “American Standard for 8mm Film”. Journal of the SMPE, 36:3 (March): pp. 235–241.

Society of Motion Picture Engineers (1949). “Proposed American Standard Location and Size of Picture Aperture of 8-Millimeter Motion Picture Cameras” & “Proposed American Standard Location and Size of Picture Aperture of 8-Millimeter Motion Picture Projectors”. Journal of the SMPE, 52:3 (March): pp. 345–348.

Tepperman, Charles (2014). Amateur Cinema: The Rise of North American Moviemaking, 1923–1960. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Thompson, Lloyd (1947). “The Movie-Sound-8 Projector”. Journal of the SMPTE, 49:5 (Nov.): pp. 463–467.

Wasson, Haidee (2021). Everyday Movies: Portability and the Transformation of American Culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Zimmermann, Patricia (1995). Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Further viewing:

Prelinger Archives (USA/global) (accessed June 14, 2024): https://archive.org/details/prelingerhomemovies?query=8mm

Southside Home Movie Project (accessed June 14, 2024): https://sshmp.uchicago.edu/archive/format/8mm

Laboratório Universitário de Preservação Audiovisual (Brazil) (accessed June 14, 2024): https://lupa.uff.br/base-de-dados-do-acervo-de-filmes-do-lupa/

Cineteca Nacional de Chile (Chile) (accessed June 14, 2024): https://www.cclm.cl/colecciones/coleccion-peliculas-familiares-1920-1980/

Colonial Film (UK/Former British Colonies) (accessed June 14, 2024): Moving Images of the British Empire: http://www.colonialfilm.org.uk/search-content?keys=8mm&sortfield=%40weight

La Red Del Cine Doméstico (Spain/global) (accessed June 14, 2024): http://lareddelcinedomestico.com/search/?q=8mm

Open Memory Box (Germany) (accessed June 14, 2024): https://open-memory-box.de

Home Made Visible (Canada/global) (accessed June 14, 2024): https://homemadevisible.ca/home-movie/

The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision (Netherlands/global) (accessed June 14, 2024): https://peertube.beeldengeluid.nl/c/afp/videos

Patents

Coors, Fritz Jr. 1931. Method for Producing Motion Picture Film. US Patent 1,905,442, filed June 2, 1931; issued April 25, 1933.

Compare

Related entries

Authors

Charles Tepperman is Associate Professor of Film Studies at the University of Calgary. Andrew Watts is PhD Candidate in the Communication and Media program at the University of Calgary.

Andrew Watts is PhD Candidate in the Communication and Media program at the University of Calgary.

This article draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.tep

Tepperman, Charles & Andrew Watts (2024). “8mm”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.