Developed by the American Mutoscope Company in 1895–1896, the Mutograph camera employed a unique wide-gauge format which delivered motion picture images of exceptionally high quality. Its films were shown to large audiences by the Biograph projector, or were viewed individually as flicked photographs in a coin-operated Mutoscope peepshow.

Film Explorer

American Biograph no. 132, Sausage Machine (1897). Hand-colored frame clipping.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

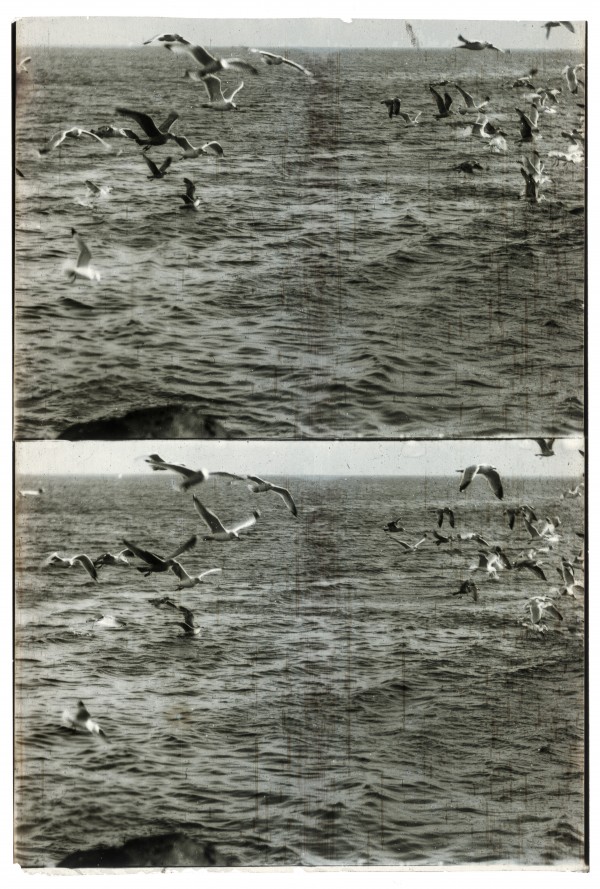

British Biograph no. E301, Feeding Seagulls, Portrush, Ireland. Filmed by W.K.L. Dickson and Emile Lauste on 22 January 1899. Frame clipping.

Cinémathèque française, Paris, France.

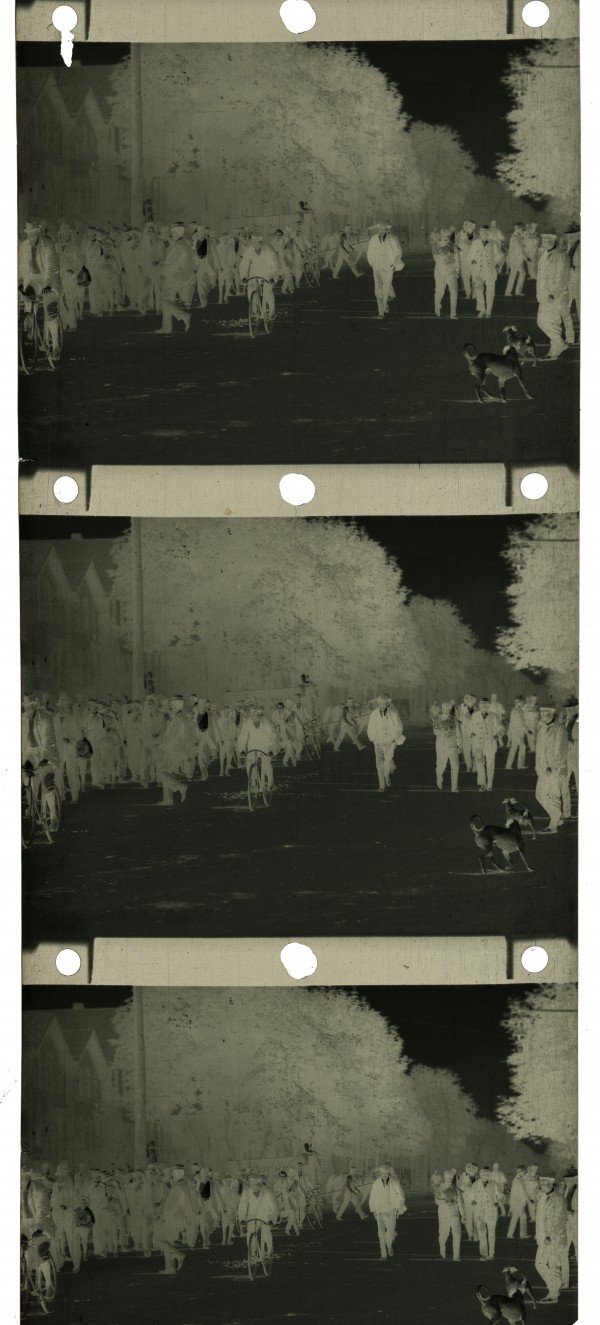

Unidentified frame clipping, date unknown. Negative with two holes punched by camera, apparently typical of European Biograph practice.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

American Biograph no. 1081, Buffalo Fire Department (1899). Negative punched within camera with three holes, typical of American Biograph practice.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Identification

Although Biograph film is frequently described as 68mm wide (2 11/16 in) interpretations of the gauge vary. The American Mutoscope and Biograph Company described their films as being 2¾ inches wide (69.85mm) and their chief cameraman, Johann Gottlob Wilhelm “Billy” Bitzer, recalled a 2 23/32-inch (69.06mm) gauge. Henry Hopwood, in 1899, reported that “the film employed is 2¾ inches wide, the pictures themselves measuring about 2 by 2½ inches” (a confusing description, as Biograph images occupied the entire width of the projected film). Mark van den Tempel reported in Griffithiana that random measurements of prints in the Eye Filmmuseum provide widths ranging from 66mm to 68mm. It has been suggested that some films may have shrunk.

No perforations

B/W regular still camera film.

The image fills the entire width of the film. There are no edge markings.

Standard Eastman stills camera roll film was used, which was thinner than 35mm motion picture film.

Usually around 30 fps, but could be varied.

1

Most films were released in B/W, however some films did feature hand coloring, perhaps applied by local exhibitors.

None

Films were silent but usually presented with live musical accompaniment. In the UK, a small number of ‘Biograph Dramatised Songs’ combined films with a vocal accompaniment.

Approximately 69.85mm x 50mm (2¾ in x 2 in), based on measurements originally distributed by the American Mutoscope Company. Unknown

Regular orthochromatic B/W still camera roll film, initially supplied by the Eastman Company, Rochester, NY.

The image fills the entire width of the film. There are no edge markings.

History

The wide-gauge Biograph originated with ambitious plans to provide alternatives to Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope movie viewer, a device which had introduced 35mm celluloid film. Operating as the KMCD combination from the summer of 1894 (named after the company’s founders) and as the American Mutoscope Company from December 1894, Herman Casler, W.K.L. Dickson, Elias Koopman and Harry Marvin originally envisaged several lightweight novelty devices employing flicked paper photographs to provide the illusion of movement. The highly successful Mutoscope viewer was eventually introduced, but not until the company had already made rapid advances in the field of projected films. Dickson had previously played a major part in developing Edison’s Kinetograph camera and Kinetoscope viewer, making it probable that the unusual technical features of Biograph’s equipment originated in an attempt to avoid patent infringement claims.

Unable to use Edison films to supply images for their viewing devices, the group were compelled to design their own camera. Planning started in November or December 1894, with a prototype machine completed by March 1895. Like the Kinetograph, the Mutograph camera was operated by electricity, but, unlike the earlier device, it employed far larger film. The individual photographs employed in the Mutoscope viewer were printed on bromide paper from wide-gauge negatives, making them better defined than the tiny images of Kinetoscope. By June 1895, the American Mutoscope Company’s first subject, a sparring match between Casler and Marvin, had been filmed outside a workshop at Syracuse, New York.

The initial decision to produce a projector was perhaps influenced by Dickson’s experience with the Latham family, with whom he worked covertly during 1894 and 1895. Although the results achieved by their Eidoloscope were sometimes flawed, a series of exhibitions across the US in the second half of 1895 demonstrated the market potential for projected films. But despite experiments with projection as early as November 1895, and an extensive filming campaign undertaken by Dickson (assisted by “Billy” Bitzer) from April 1896, the Biograph projector was not publicly exhibited until September 1896 – several months after the first showing of Edison’s Vitagraph, the Lumière Cinématographe and Birt Acres’ Kineopticon. But with a larger, clearer image and a comparative lack of “flicker” as a result of its faster projection rate, Biograph soon became established as the market leader in the United States.

From an early stage, the American Mutoscope Company was an ambitious, large-scale organisation with extensive financial backing from a consortium of bankers and industrialists. An open-air studio on the roof of the company’s New York City HQ at 841 Broadway, New York City, turned out short fiction films on a weekly basis from early 1897, while Biograph cameramen roamed the country securing views of sporting occasions, national events and – a Biograph trademark – travelling shots from trains and boats. In November 1899, the company conducted a major experiment with artificial lighting, filming the whole of the championship boxing contest between Jim Jeffries and Jack Sharkey under a massive installation of electric arc lamps in an indoor arena at Coney Island, New York City. When a court decision rejected all Edison’s patent claims in March 1902, the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company began the switch to 35mm production, filming many subjects in an electrically lit indoor studio at East Fourteenth Street, New York (opened 1903). Between 1895–1903 the company had made more than 2,000 wide-gauge films. After shedding the restrictions of the wide-gauge format, Biograph became one of the world’s main producers of fiction films, with its lead director D. W. Griffith establishing many key elements of a rapidly evolving narrative genre.

Biograph became an international brand when an offshoot of the company was set up in England in 1897. Within months the British Mutoscope and Biograph Syndicate (British Mutoscope and Biograph Company from 1899) became established as the largest and most prestigious British film concern. The company was expansionist in both operation and organization. Its chief filmmaker, W. K. L. Dickson (often assisted by Emile Lauste), filmed events in many countries; took “animated portraits” of European politicians, royalty, and religious leaders; and secured an outstanding record of the Anglo–Boer War in South Africa in 1899-1900. British Mutoscope and Biograph also promoted a worldwide network of companies who co-operated closely during the late 1890s and early 1900s. Like their American counterpart, the company introduced artificial lighting at an early stage, filming a battle scene from Shakespeare’s Henry V inside the Lyceum Theatre, London, in January 1901 and, more significantly, opening an innovative indoor studio at 107 Regent Street, London, from 1900. Having made around 1,300 wide-gauge films, the British company moved to 35mm production in 1903. Although remaining a leading film company for some years, the British concern did not replicate the success of American Biograph and it ceased to function before World War I. The Biograph and Mutoscope company for France had a brief, but productive existence, issuing around 400 wide-gauge subjects, while it was outlived by the Deutsche Mutoskop und Biograph Gesellschaft which had produced 300 wide-gauge films by 1902.

Selected Filmography

Extended views of a German town taken from a moving carriage suspended under a monorail. Copy at MoMA, New York.

Extended views of a German town taken from a moving carriage suspended under a monorail. Copy at MoMA, New York.

A view from the front of a locomotive, filmed in 1897 and often described as the first “Phantom Ride”. Copies at BFI National Archive, London and Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

A view from the front of a locomotive, filmed in 1897 and often described as the first “Phantom Ride”. Copies at BFI National Archive, London and Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Taken from a second train running on a parallel track. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Taken from a second train running on a parallel track. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Steam-driven fire engine rapidly approaches camera. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Steam-driven fire engine rapidly approaches camera. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Celebrated English actor Herbert Beerbohm Tree, in a scene from his production of Shakespeare’s play. One of four scenes from King John which provided Biograph with added cultural prestige. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Celebrated English actor Herbert Beerbohm Tree, in a scene from his production of Shakespeare’s play. One of four scenes from King John which provided Biograph with added cultural prestige. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

A dramatically framed image of the launch of the world’s largest ship. Copies at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam and MoMA, New York.

A dramatically framed image of the launch of the world’s largest ship. Copies at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam and MoMA, New York.

An early publicity shot showing the presidential candidate William McKinley. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

An early publicity shot showing the presidential candidate William McKinley. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

A deeply layered view of the aftermath of an actual battle, taken by Dickson in South Africa. Copies at BFI National Archive and Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

A deeply layered view of the aftermath of an actual battle, taken by Dickson in South Africa. Copies at BFI National Archive and Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

The most widely shown of a series of views of the head of the Roman Catholic church filmed by Emile Lauste and Dickson in the Vatican, Rome. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

The most widely shown of a series of views of the head of the Roman Catholic church filmed by Emile Lauste and Dickson in the Vatican, Rome. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Tracking shot along one of Amsterdam’s main waterways, taken by Emile Lauste. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Tracking shot along one of Amsterdam’s main waterways, taken by Emile Lauste. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

One of the most popular Biograph films, depicting three children and a flurry of feathers. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

One of the most popular Biograph films, depicting three children and a flurry of feathers. Copy at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

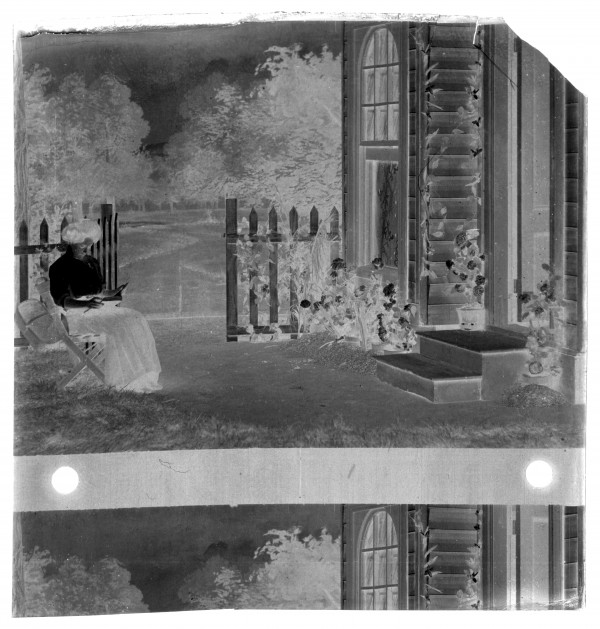

The first of six scenes showing the famous American actor Joseph Jefferson in Rip Van Winkle. Copy at BFI National Archive, London.

The first of six scenes showing the famous American actor Joseph Jefferson in Rip Van Winkle. Copy at BFI National Archive, London.

“Biograph Film No. 1” taken on August 5, 1895. This film is not known to exist.

“Biograph Film No. 1” taken on August 5, 1895. This film is not known to exist.

Technology

Biograph’s 68mm film was significantly larger than standard 35mm and provided far more detailed views and facilitated the projection of far bigger projected images. Comparable in size to a modern IMAX frame, it has been estimated that the information carrying capacity of Biograph film equates to 8–16K resolution in digital data.

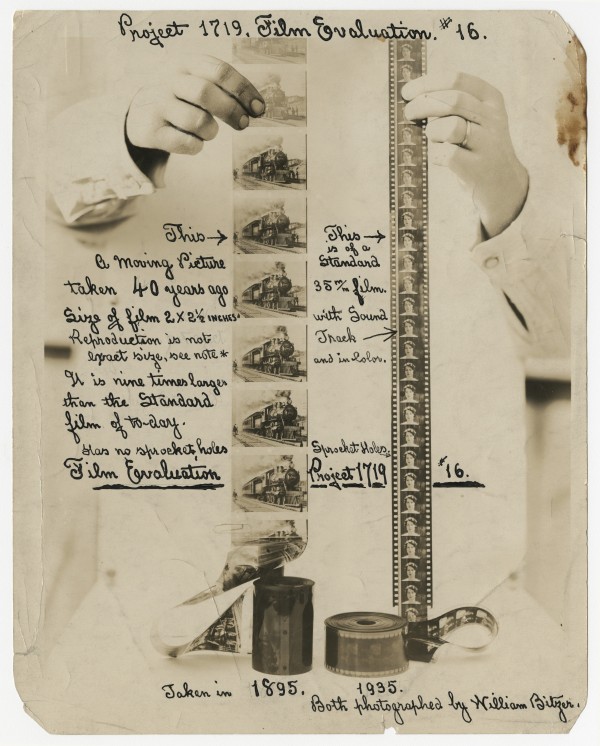

The designs for the Mutograph camera, Biograph projector and Mutoscope peepshow appear to have been dictated by legal considerations. To distance themselves from Edison’s (in effect, Dickson’s) inventions, the company decided not to punch sprocket holes before photography, as was the case for the film strips used in conjunction with the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope. Instead, film was transported by a friction-based movement which held individual frames steady for an instant by the intermittent grip of two wooden rollers. To avoid the regular spacing of Kinetograph frames, an irregularity of spacing was introduced, a potential difficulty which was rectified in the printing process by an ingenious mechanism (the original patent specification ran to 17 pages of text and 13 pages of drawings). As the film negative was exposed, two or three holes were simultaneously punched between each frame, their position, always remaining precisely the same in respect to the image. The film was then “step printed” one frame at a time, with spring loaded pins in the printer locating the reciprocal sets of punched holes in the negative to ensure stability and registration. Positive prints usually show no sign of the registration holes. Like the Mutograph camera, the Biograph projector was extremely heavy and reliant on electricity. The wooden roller friction intermittent movement from the camera was retained, with a manually controlled clutch allowed the operator to adjust for inevitable film slippage.

Display created by “Billy” Bitzer, demonstrating the difference between Biograph large-gauge film and standard 35mm film. Although a positive print, the Biograph film shows three punch holes between frames.

Billy Bitzer collection, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

References

Bitzer, “Billy” (1973). Billy Bitzer. His Story. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Brown, Richard & Barry Anthony (1999). A Victorian Film Enterprise. The History of the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company, 1897-1915. Trowbridge, Wiltshire, UK: Flicks Books.

Hendricks, Gordon (1964). The Beginnings of the Biograph. The Story of the Invention of the Mutoscope and the Biograph and their Supplying Camera. New York: Beginnings of the American Film.

Meusy, Jean-Jacques & Paul Spehr (1997). “Les débuts en France de l’American Mutoscope and Biograph Company”. Histoire, Economie et Sociéte, 16:4: pp. 671–708.

Reizi, Paulina (2020). “Reviving the Nineteenth Century 68mm Films with the Latest Digital Technologies”. New York: MCN Publications (Museum Computer Network). https://publications.mcn.edu/2020-scholars/reviving-films/

Spehr, Paul (2008). The Man Who Made Movies: W.K.L. Dickson. New Barnet, UK: John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

“The Wonders of the Biograph” (1999/2000). Griffithiana, 66–70. Essays by Luke McKernan, Paul C. Spehr, Richard Brown, Deac Rossell, Barry Anthony, Stephen Bottomore, Mark van den Tempel and Nico de Klerk.

Patents

Casler, Herman. Mutoscope. US patent US549,309, filed November 21, 1894, and patented November 5, 1895.

Casler, Herman, Kinematographic Camera. US patent US629,063, filed February 26, 1896, and patented July 18, 1899.

Casler, Herman, Consecutive-View Apparatus, US patent US666,495, filed February 26, 1896, and patented January 22, 1901.

Casler, Herman, Photographic-Printing Machine, US patent US731,282, filed May 21, 1898, and patented June 16, 1903.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Barry Anthony is a social historian with a particular interest in film and theatre. He has written extensively on many aspects of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century popular culture.

Anthony, Barry (2024). “Wide Gauge Biograph”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.