The first motion picture device presented publicly for rapidly photographing a long series of images on a roll of film.

Film Explorer

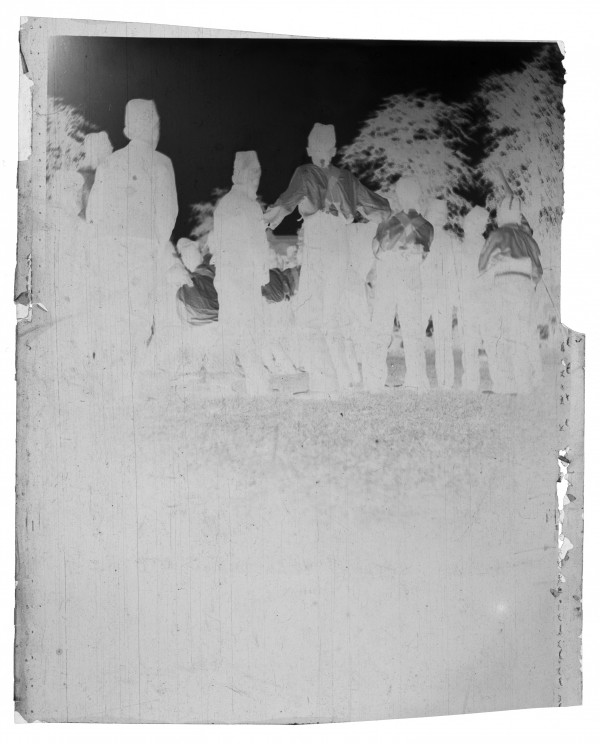

A recently rediscovered frame of 68mm camera negative from the Machine Camera showing a group of children in uniform at an organised event in a park, probably London, 1890. Documentation indicates this frame clipping was sent to Earl Theisen by Will Day in the early 1930s.

Film Frame Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

68mm camera negative of Promenaders by the Serpentine in Hyde Park (William Friese-Greene, 1890).

Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée (CNC), Bois-D’Arcy, France.

Identification

Paper negative (1889), Cellulose Nitrate (Eastman Transparent Film) (1890).

63mm x 63mm (2.5 in x 2.5 in).

26 pinholes on both sides of film.

B/W orthochromatic.

History

William Friese-Greene (1855–1921) was born William Edward Green but took on the surname of his first wife, Helena Friese (1850–1895) after they married in 1874. Born into a working-class family in Bristol, he found success as a photographer in Bath from 1876, gradually turning his name into a brand for a chain of studios in the West of England, before moving to London in 1885 and repeating his success there. An innovator in commercial photographic products and with a gift for marketing, Friese-Greene was very active within the Photographic Society of Great Britain, while pouring a lot of the income from his businesses into invention. In Bath, he had known and worked with John Rudge (1837–1903), who created various devices to project an illusion of movement from posed photographs. In London, Friese-Greene began to take the idea further – to capture live action, first on glass, then sheets of film and eventually roll film.

On June 21 1889, Friese-Greene applied for British patent 10,131 with Mortimer Evans (1836–1921), an English civil and mining engineer, based in Glasgow, with a strong interest in electrical matters who had no known previous experience in photography, but who may have met Friese-Greene through the British Association or one of the other scientific organisations they were both active in (Domankiewicz, 2024). Their patent was described as ‘Taking Photographs in a Rapid Series with a Single Camera and Lens’, thus defining itself as distinct from the work of Eadweard Muybridge and Ottomar Anschütz, or the patent of Louis Le Prince.

From June through to September the firm of A. Légé & Co. in Hatton Garden, London constructed a camera for Friese-Greene, but this camera was not the same as the one in the patent. It was larger, was geared to take pictures more rapidly, and the film travelled downwards, rather than upwards. A smaller, ‘Kodak size’ camera to the pattern of the patent may have been made later and this ‘improvement’ appeared to be connected with Evans (Domankiewicz, 2024).

Friese-Greene took possession of the larger camera on September 26, 1889 and generally referred to it as a “Machine Camera”. He soon bought out Evans’ share of the invention but, apart from a couple of premature disclosures in the press, it remained under wraps until the domestic and foreign patents had been dealt with (Anon., 1889; Friese-Greene, 1889). On February 25,1890, Friese-Greene showed the camera to the Bath Photographic Society and displayed strips of film shot with it (Friese-Greene, 1890). That week it was extensively described and illustrated in The Photographic News, a report that then appeared in Scientific American in April (Anon., 1890a & 1890c). It would also be written about in France and Germany (David & Charles, 1892). Friese-Greene claimed a speed of ten frames per second with his camera, which was theoretically achievable, as it exposed four frames with a single turn of the handle (Brown, 1909a).

This was the very first camera to be publicly disclosed for taking a rapid series of photographs on a roll of film with the aim of synthesizing and reproducing motion – Le Prince having worked in secret, Edison’s work unseen at that time and Marey being interested only in the analysis of movement via short strips of film.

In September 1889, only paper negative, or stripping film was commercially available in rolls in Britain, but the first samples of Eastman Transparent Film arrived in the UK in November 1889 and it went on sale in January 1890. It is therefore likely that Friese-Greene initially used paper film.

Friese-Greene stated that the first film he shot was of traffic at Hyde Park Corner, but this film is lost, as are most of the test films he made. All that remains are a short celluloid sequence taken on the path beside the Serpentine at a slow frame rate, a print of a short piece of film reproduced in Kinematograph Weekly in 1909, taken in a London street, and a recently unearthed frame of negative. Friese-Greene was working on a lantern/projector in 1890 and one was constructed for him by Légé and Co in the first half of the year. His plan was to project images with it at the Photographic Convention at Chester in June 1890. However, in the event, the projector was not working, so he showed the camera, displayed a long strip of film of people walking on Haverstock Hill, north London, and showed a sequence of a hand opening and closing using a box device with a 3-ft (0.9m), built-in screen (Watkins, 1933).

Friese-Greene would continue experimenting with moving pictures through the early 1890s and then patent new equipment in 1896 as the film industry took off, continuing to invent throughout the rest of his life, particularly in the field of colour cinematography.

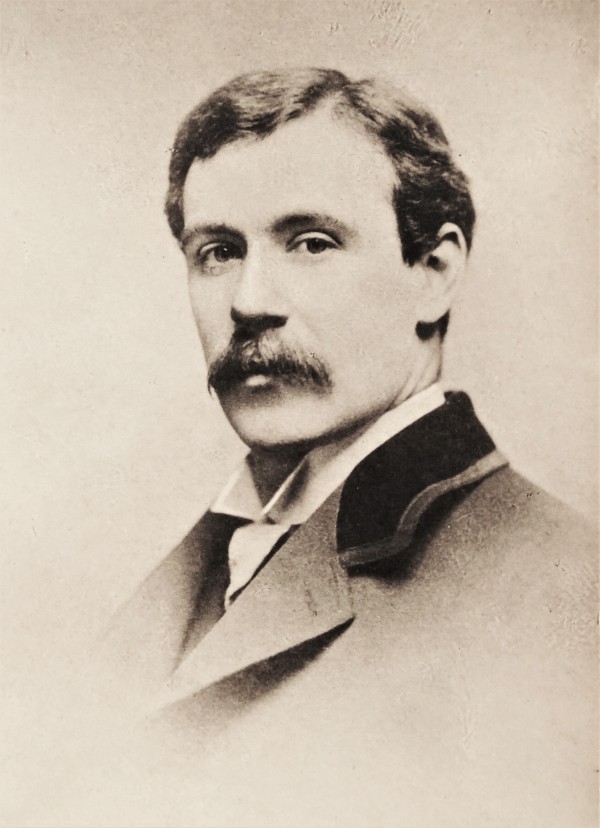

Portrait of William Friese-Greene, taken around the time of his first film cameras, 1889–90, probably by the famous portrait photographer Henry Vander Weyde.

National Science & Media Museum, Bradford, United Kingdom.Portrait of William Friese-Greene, taken around the time of his first film cameras, 1889–90, probably by the famous portrait photographer Henry Vander Weyde.

Selected Filmography

Probably photographed on paper negative.

Probably photographed on paper negative.

Photographed on celluloid. 26 frames survive at the Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée (CNC) in France, cut into strips. CNC reconstructed this on 35mm around 1998, catalogued as Hyde Park, London.

Photographed on celluloid. 26 frames survive at the Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée (CNC) in France, cut into strips. CNC reconstructed this on 35mm around 1998, catalogued as Hyde Park, London.

Photographed on celluloid.

Photographed on celluloid.

Photographed on celluloid.

Photographed on celluloid.

Technology

A large format, the choice of gauge was probably defined by the rolls of film (paper negative and celluloid) being produced for the No. 1 Kodak at that time, which was designed for images 2.5 in wide, with a small margin either side, from film on a 2.75-in spool: which translates into a film slightly narrower than 70mm – around 68mm.

The Eastman celluloid film produced for stills photography in 1889–90 was far thinner than the dedicated products later created for shooting moving pictures. Eastman Transparent Film was described in contemporary publications as being between 2.5 and 3 mil (thousands of an inch) thick, whereas the later motion picture standard was 6 mil (0.18mm). This meant two things: first, it was light and flexible so should have been easy to move through a camera; secondly, it was thin and fragile, so could not take perforation without splitting.

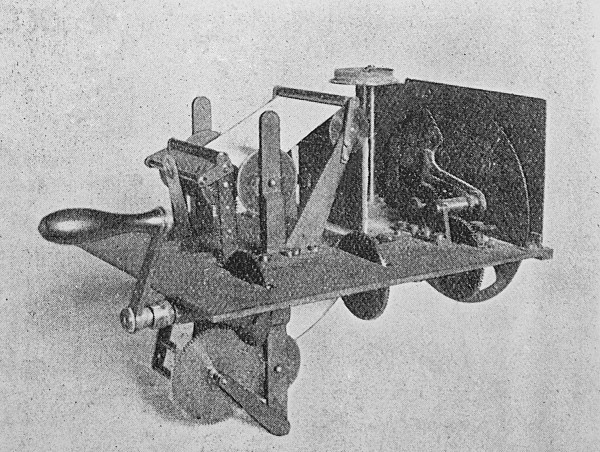

The Friese-Greene and Evans solution was to move the film via a ring of tiny pins, which pierced the edge of the film and engaged it for intermittent movement after each exposure. These pin marks – over 24 per frame up both sides of the film – can be clearly seen on the surviving examples. This did not offer the same certainty of spacing that sprocket holes later would, although the surviving strips indicate broadly consistent spacing – decay and damage making exact measurements impossible. There was a gap of around 15mm (0.59 in) between each frame. The intermittent system in the camera used a spring which wound up and then was released, turning a wheel that moved the film forward a set amount. A very similar system was later used in the Wray Motorgraph in Britain and the Lapiposcope in France, both in 1896.

In April 1890, Friese-Greene showed his camera at both the general and the technical meetings of the Photographic Society of Great Britain (later Royal Photographic Society). At the first, “It was stated that it [the camera] could be worked to take ten successive photographs in a second of time. Developed strips of the celluloid negatives many yards in length were exhibited, as well as prints therefrom” (Anon., 1890b). At the second there was a discussion about working with celluloid film where Friese-Greene described and showed dishes he had made to develop entire 20-foot rolls of film and, “He also showed a series of eighty pictures, taken very rapidly, of some people walking, where the progress in movement had only been about one foot” (Anon., 1890d).

The only surviving series of images, of promenaders by the Serpentine in Hyde Park, was taken at a very slow rate of only one or two frames per second. However, contemporary descriptions from 1890 of other films he shot, an examination of the Machine Camera in 1909 by the cinematographic expert Theodore Brown, and the accurate replica built for the Race to Cinema project in the early 2000s, broadly concur with the statements of Friese-Greene and point to a viable running speed of eight to ten frames per second. The Serpentine test film was perhaps not a trial of speed but of other functionality.

The above accounts indicate that the camera was capable of taking several frames per second and that Friese-Greene was printing from the negatives, although it is not clear if these were individual, or on a strip. In correspondence with Thomas Bolas, an expert photographic chemist, a few months later, Friese-Greene was seeking advice about how to contact print rolls of film. He was also very interested in the possibilities of ‘reversal’ film, creating a direct positive. This shows Friese-Greene intended to create continuous positive prints on film, but we do not know how far he got with this or whether his ‘lantern’ was designed to project a strip of film or a rapid series of individually mounted images. In May 1890, it was reported that, ‘Mr Chang, the Secretary to the Chinese Embassy, had a private view of the whole machine at work a few days ago, and was much interested therein’ (Anon., 1890e). Mr. Tien Fan Chang was very active in the British photographic scene. However, Friese-Greene did not project these films publicly and no positive prints have survived.

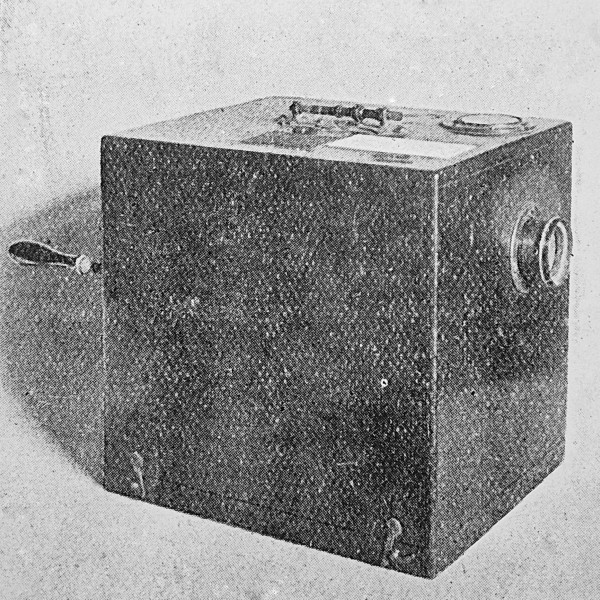

Exterior of the Machine Camera.

Brown, Theodore (1909a). “Mr. Friese-Greene and His Inventions – Part 1”. Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (July 8, 1909): p. 417.

Interior mechanism of the Machine Camera. The unperforated film was advanced in the camera by a wheel of small pins.

Reproduction of a 68mm film frame, possibly from film taken on Haverstock Hill, north London, c. Spring 1890.

Brown, Theodore (1909b). “Mr. Friese-Greene and His Inventions –- Part 2”. Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (July 15, 1909): p. 459.

References

Anon. (1889). [First report of Friese Greene & Evans Camera]. The Photographic Review (October 19, 1889): p. 189.

Anon. (1890a). “A Machine Camera for Taking Ten Photographs a Second”. The Photographic News, 34 (February 28, 1890): pp. 157–59.

Anon. (1890b). “Photographic Society of Great Britain”. British Journal of Photography, 37 (April 18, 1890): pp. 253–54.

Anon. (1890c). “A Machine Camera for Taking Ten Photographs a Second”. Scientific American Supplement , 29:746supp (April 19): p. 11921.

Anon. (1890d). “Monthly Technical Meeting”. The Photographic Journal, 30 (May 23): p. 162.

Anon. (1890e). “Remarkable Novelties in Photographic Instruments”. Photographic News, 34 (May 30): p. 421.

Brown, Theodore (1909a). “Mr. Friese-Greene and His Inventions – Part 1”. Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (July 8): pp. 415, 417.

Brown, Theodore (1909b). “Mr. Friese-Greene and His Inventions – Part 2”. Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly (July 15): p. 459.

David, Ludwig & Charles Scolik (1892). Die Photographie Mit Bromsilber-Gelatine Und Die Praxis Der Moment-Photographie. Vol. Band III. 3 vols. (Halle a. S.: Wilhelm Knapp): pp. 229–233.

Domankiewicz, Peter (2024). ‘William Friese-Greene & The Art of Collaboration’. Early Popular Visual Culture, 22:1 (March).

Friese Greene, William (1889). “Life in Shadow”. In The Yearbook of Photography and Photographic News Almanac for 1890, pp. 150–52. London: Piper & Carter.

Friese-Greene, William (1890). “Photography in an Age of Movement”. British Journal of Photography (March 7): pp. 152–53.

Watkins, Alfred (1933). “Friese-Greene and the Chester Convention of 1890”. Photographic Journal , 73 (February): pp. 77–78.

Patents

Friese-Greene, William and Mortimer Evans. 1889. Improved apparatus for taking photographs in rapid series. British Patent 10,131, filed June 21, 1889, accepted May 1890.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Peter Domankiewicz is a film director, screenwriter and journalist with a long-standing interest in the origins of cinema. He is currently working on a fully funded PhD at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK, examining the work and inventions of the controversial moving picture pioneer, William Friese-Greene. In 2023 he undertook an AHRC-funded Smithsonian Fellowship at the National Museum of American History in Washington DC, where he carried out a survey of their Early Cinema Collection, drawing attention to several overlooked figures and their inventions. He has written about early film for Sight & Sound and The Guardian, contributed to reference works and academic journals and co-authored a book with Deac Rossell & Barry Anthony, Finding Birt Acres (University of Exeter Press, forthcoming 2024) about Britain’s first commercial filmmaker. He has given talks at conferences, symposia, film festivals and BFI Southbank. His blog William Friese-Greene & Me, presents original research on early film history for a broad readership.

Toni Booth at the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, UK. Laurent Mannoni at the Cinémathèque française, Paris, France. Laraine Porter at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK.

Domankiewicz, Peter (2024). “Friese-Greene Machine Camera”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.