A 35mm 360-degree cylindrical dome projection format developed by Adalbert Baltes – introduced in 1958 at Photokina Köln, Germany.

Film Explorer

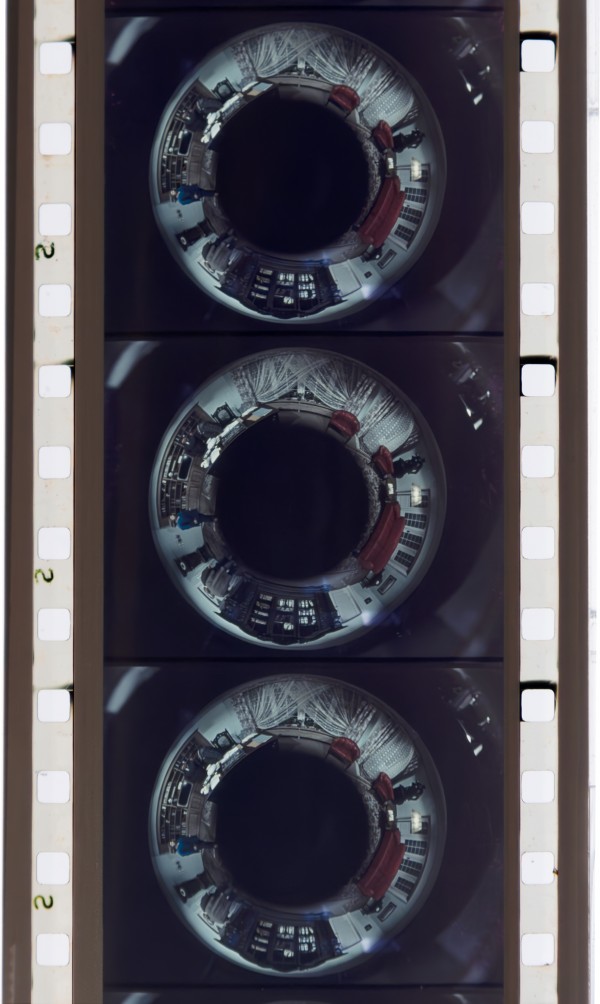

A 35mm Cinetarium print of Die Nacht ohne Ende (1963). The circular image was projected on an immersive domed screen, while four channels of magnetic sound provided directional audio within the auditorium.

Courtesy of Magnus Rindisbacher.

Identification

At least one surviving print is on Ferraniacolor stock.

Standard Eastman Kodak or Ferrania edge markings, black text.

1

Original Eastmancolor or Ferraniacolor prints now likely suffer from color fading.

cinetarium film

The surviving print of Die Nacht ohne Ende (1963) has four magnetic stripes. The four soundtracks were likely to have played to individual speakers placed at specific positions within the auditorium, relating to action taking place on-screen.

Color

Unknown

History

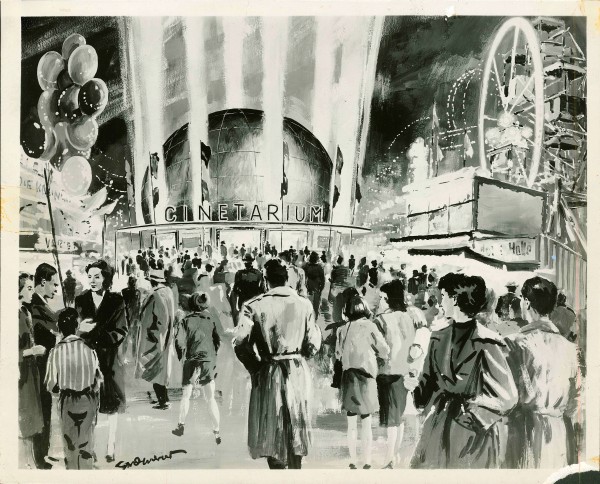

Adalbert Baltes, a “pilgrim on the path of total immersion” (Reißmann, 2006: p. 17), first presented plans for his Cinetarium at the Photokina 1958 trade fair in Cologne, Germany. This special-venue immersive projection format used a domed screen with a diameter of 7m (22.97 ft), in an auditorium that could seat 45 people. Baltes, from Hamburg, Germany, was an inventor of experimental media, and a filmmaker and producer for culture-, image- and industrial films.

Baltes had various plans to project an immersive wraparound image. Historians Reißmann, Tröbst, Piccolin and Wulff describe a cylindrical projection, achieved with the help of a spherical mirror, or projected directly onto the surrounding dome screen through a clustered arrangement of projectors (Piccolin/Wulff, 2007: pp. 3–4; Reißmann, 2006: pp. 17–21; Tröbst, 1957: pp. 9–14). Baltes's original vision was for a permanent venue, a large “spherical structure made of concrete, steel and glass [...], looking like Saturn with its rings” (Tröbst, 1957: p. 9) – but these plans didn’t come to fruition. In 1959/60 Baltes sold his Cinetarium-related patents to filmmaker Bill Rebane in the United States and Moulin Rouge manager Jean Bauchet in France. Due to legal complexities, the sales did not lead to any new Cinetarium installations, however Rebane did apparently shoot and exhibit new footage in Chicago.

In Germany – where he retained the rights – Baltes planned the construction of a dedicated Cinetarium theater. In 1963, Baltes bought the Imperial Filmtheater (formerly Non-Stop-Aktualitätenkino) at Reeperbahn 3 in Hamburg, Germany. He rebuilt it and opened his 360-degree cinema on June 27, 1963, under the Cinetarium name. The film Fata Morgana (1963) was to be presented to the audience at the opening, but it appears that production on the film was never completed. The only film known to have been screened at the theater was called Die Nacht ohne Ende (Cinema Treasures, n.d.). Baltes eventually sold the theater in 1966 (Roe, 2020).

Selected Filmography

Various short demonstration films, animation tests and advertisements for Ford and Konsum coffee, survive at the Kinemathek Hamburg.

Various short demonstration films, animation tests and advertisements for Ford and Konsum coffee, survive at the Kinemathek Hamburg.

The only film completed and screened at the Cinetarium in Hamburg. The cast included Petra Schmidt and Peter Wienke.

The only film completed and screened at the Cinetarium in Hamburg. The cast included Petra Schmidt and Peter Wienke.

An unfinished production intended for the opening of the Cinetarium theater in Hamburg, Germany.

An unfinished production intended for the opening of the Cinetarium theater in Hamburg, Germany.

Technology

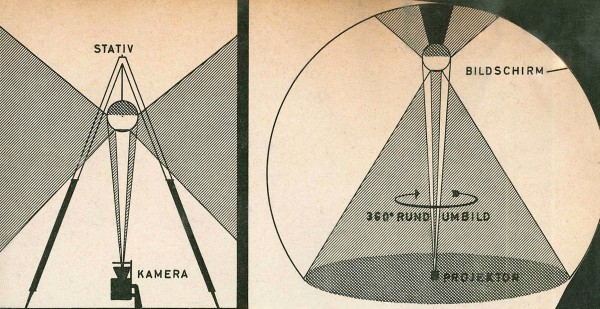

The Cinetarium process projected a circular image from 35mm film onto a domed screen. The projector pointed vertically, with its images reflected onto the sides of the spherical screen from a mirrored ball mounted near the top of the dome. The resulting rectified image appeared as a seamless wide band on all sides of the viewer. The 35mm print had CinemaScope perforations with magnetic stripes on either side that contained four channels of directional audio that followed the action on screen.

The scenes were shot in a similar manner to the projection. The camera was mounted pointing vertically up and captured a 360-degree view at right angles to the camera, as one seamless image. On the film, the image appeared in a ring shape within a rectangular frame. The center of the frame and the outer edges would have been masked in projection. All surviving films are in color. Both live-action and animation footage was photographed.

Filming (left) was achieved by pointing the camera vertically to record a band of images reflected off a mirrored ball mounted above. Projection (right) was accomplished by reflecting the projector beam on a mirrored ball to create a 360-degree image (“360° rundumbild” [“all-round picture”]) on a domed screen (“bildschirm”).

Adalbert Baltes (right), and a colleague, preparing the vertically mounted film camera with spherical mirror rig for shooting a Cinetarium film.

Adalbert Baltes testing Cinetarium in his home-built theater, c. late-1950s. The screen wraps seamlessly around the auditorium. The projector, here positioned at the feet of Mr. Baltes, is reflected onto the screen by the mirrored ball, supported above from the ceiling of the dome. Viewers were able to turn in their chairs to face the different parts of the screen as the action moved.

Publication unknown. Bill Rebane Collection, Merrill Historical Society, Merrill, WI, United States.

References

Anon. (1959). “Herb’s Monday Blues”, Tribune (May 4).

Anon. (1960). “Göttinger Erfindung in den USA”. Göttingen Zeitung, 28 (February 3).

Cinema Treasures (n.d.). “Imperial Theater”. https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/60490 (accessed October 1, 2024).

Kießling, Maren (2023). “Zylindrische und hemisphärische Bewegtbildprojektionen – eine Einführung”. https://www.academia.edu/102388099/Zylindrische_und_hemisph%C3%A4rische_Bewegtbildprojektionen_eine_Einf%C3%BChrung (accessed October 1, 2024).

Piccolin, Lukas & Hans J. Wulff (2007). “Simultanprojektion”. In: Rundumkinos. Vom Panorama zu 360°-Filmsystemen (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere), Vol. 87, Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik.

Piccolin, Lukas (2012). “Circle-Vision 360”. In: Das Lexikon der Filmbegriffe, University of Kiel, Online-kompendium. http://filmlexikon.uni-kiel.de/index.php?action=lexikon&tag=det&id=3701 (accessed October 1, 2024).

Rebane, Bill (n.d.). “Bill Rebane Collection”, Merrill Historical Society, Merrill, WI, United States.

Reißmann, Volker (2006). “Ein Visionär auf dem Weg zur totalen Immersion: Adalbert Baltes”. Hamburger Flimmern: Die Zeitschrift des Film- und Fernsehmuseums Hamburg e.V., 13 (December): pp. 17–21.

Tröbst, Cord-Christian (1957). “Cinetarium – Kintopp in der Kugel”. Hobby: Das Magazin der Technik, 3: pp. 9–14.

Patents

Baltes, Adalbert. Vorsatzobjektiv zur aufnahme und wiedergabe von stehenden und lebenden bildern. German patent DE1775044U, filed July 2, 1958, and issued October 2, 1958. https://patents.google.com/patent/DE1775044U

Baltes, Adalbert. Vorrichtung zur aufnahme und wiedergabe von stehenden und lebenden bildern in kugelform. German patent DE1812968U, filed February 12, 1958, and issued June 9, 1960. https://patents.google.com/patent/DE1812968U/

Compare

Related entries

Author

Dr. Maren Kiessling is an author, scientist and filmmaker, and is a lecturer in film at the Martin-Luther-University, Halle (Saale), Germany. As a filmmaker she has worked as camera operator, director, producer and editor. She has also worked for the international art film festival Werkleitz (2013–15) and has organized the international short-film festival Monstrale (2013–17). Her areas of academic research include full-dome cinema and the dramaturgy of the image. www.marenkiessling.de

My thanks to Thomas Pfeiffer from Kinemathek, Hamburg, Brandon Johnson, Lucas Piccolin and Volker Reißmann!

Kiessling, Maren (2024). “Cinetarium”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.